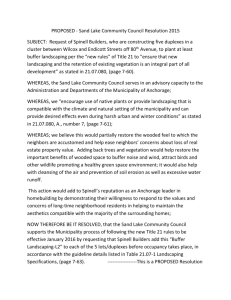

Sustainable Landscaping - Association of Compost Producers

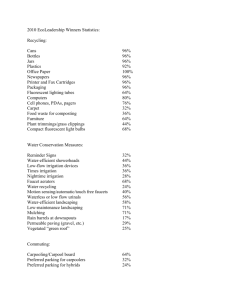

advertisement