Worse than the Tourists: Non-Native Invasive

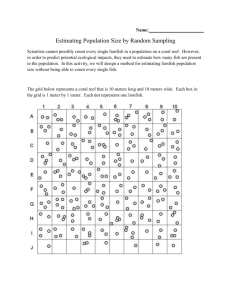

advertisement