Admin Law Outline_Banzhaf

advertisement

Admin Law Outline

Topic 1: Introduction to Administrative Law

I.

II.

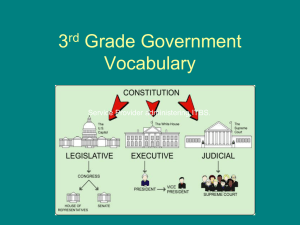

Definition: Administrative law is the body of general rules and principles governing administrative

agencies (How they do their own work, and how work results can be viewed or reviewed by the President,

Congress and Courts)

a. Functions: Administrative law is NOT the substantive law adjudicated by agencies, or the

procedure followed by agencies

i. (1) Rulemaking- Regulations promulgated by agencies (CFR)

1. Under agency rulemaking power, agencies can pass criminal statutes violation of

which can be a felony

ii. (2) Adjudication- Social security/immigration decisions

1. Decide specific factual situations

2. More cases adjudicated in agencies than cases filed in federal courts

b. Source: Constitution, federal statutes, E.O.’s, court decision, and agency’s own rules and guidelines

i. Agency organization dictated by statute (NOT constitution)

ii. Focus: Process-oriented (as opposed to tax law practiced by IRS)

iii. Administrative Agencies: Any governmental authority other than a court or a legislative

body- “All authorities and operating units of the government except for the constitutionally

established entities” (Congress, President and Courts)

iv. Created by statute (definitions under APA on page 1437 and 1404)

c. Goals: Admin law attempts to increase social/political freedom by making government

interworking’s more transparent and encouraging individual gov’t participation

i. Many agencies have a division of functions to keep ALJ’s isolated

1. But not always – OSHA is the inspector, judge and jury

2. Newer agencies have more energy, before negative precedent

d. Output: Agencies make regulations (CFR), decide disputes, license activities or individuals, enforce

regulations (inspect, penalties)

i. Not all elements are listed in organic statute- might be listed in later statutes

Types of Agencies: Two patterns for agency organization

a. Administrative Agencies: Headed by single administrator who serves at President’s pleasure, often

within larger entities headed by members of President’s Cabinet

i. Non-Independent (within the executive branch)- led by one person

1. Pres. has near unlimited power to dismiss for whatever reason

ii. Ex: OHSA or Dept. of Labor (usually Administrators)

iii. Sometimes independent agencies are housed within administrative agencies (FERC within

DOE- 5 members have term appointments and removal protection making it “independent”)

b. Independent Regulatory Commissions: Free standing bodies whose members can be removed

from office by President only for “cause”

i. Until 1910 all agencies were within the executive branch (State, DOD, DOJ, etc.), then

Congress created more agencies with a certain amount of independence from the executive

branch

ii. Sometimes headed by people (usually Commissioners) who have term tenure or for-cause

removal protection- are not subject to immediate dismissal by President (with exceptions).

1. Sometimes independent agencies have a single individual who has term tenure and for

cause removal protection (SSA)

c. Regulatory Agencies: Issuing rules, inspecting or punishing violation w/ governmental authority

d. Non-Regulatory: Agency reaches outside its own area to achieve results by traditional government

means

i. Not using governmental powers (GSA- has an impact on things outside their spheres)

ii. Ex: National Zoo is not a regulatory agency because they just regulate behavior within their

sphere

e. Examples: Some agencies deal with small area- FCC deals with broadcasters exclusively, some

with wide area- OSHA- anyone who employs someone

1. Non-Independent and Non-Regulatory: State department, FBI

2. Non-Independent and Regulatory: FDA, OSHA: Within HHS which is under the

department controlled by an executive

3. Independent and Non-Regulatory: CIA, NASA, influence outside conduct

4. Independent and Regulatory: FTC, NRLB, NRC – insulated from Presidential control,

multi-member heads, fixed terms, for-cause removal

f. Presidential Preferences

i. Carter- wanted to inventory all agencies

ii. Reagan- wanted cutback on agencies (deregulation)

1. Many political initiatives require new agencies

iii. Clinton- wanted to reform Medicaid, required new bureaucracy

iv. Bush- 9/11 made him increase expansion in agency (size & number)

v. Obama- Greatly expanded administrative agencies

1. TARP, stimulus funds, auto industry, Dodd-Frank, CFPB

g. Issues: Alternatives to establishment of administrative agencies

i. Issue with unelected bureaucrats getting policy and discretionary power

ii. Step 1: Is there a problem? Do we need to get the government involved?

1. Organ donation- voluntary

2. Common law regimes: Courts

3. Statutory law regimes: Legislature, enforceable by Court

iii. Step 2: Do we even need an agency to remedy the problem?

1. Need uniformity, special experience or expertise, etc.

iv. Step 3: How should it be addressed?

1. Courts- Usually can address, unless there is no law to apply to the topic

2. Legislature- Congress can pass a statute setting out the substantive law, but

sometimes don’t want congress making specialized decisions

3. Agencies- Give an existing agency new authority, or new agency?

III.

Procedure

a. Congress has broad authority to create and structure agencies subject to certain constitutional

limitations

i. Might think Agencies violate Separation of Powers (co-mingling of legislative, executive and

judicial functions AND indep. agency’s insulation from presidential oversight)

ii. But constitution authorizes Congress to make laws “necessary and proper” for ensuring

powers are exercised effectively – (Art I, §8, cl. 18)

b. Agencies can only exercise powers they have been delegated, but Congress entrusts agencies with

many policy-setting powers, and high “discretion”

i. Jurisdiction can be vague like “in the public interest” or “to protect public health”

Topic 2: Delegation of Regulatory Lawmaking Power (Rulemaking/Legislative Power)

I. Delegating to the President v. Cabinet

a. The Non-Delegation Doctrine: Legislative power delegated to Congress cannot be re-delegated to

the Executive or to the Courts

i. Congress can’t delegate legislative powers to agency – Constitution gives congress

responsibility to exercise “all legislative power” – (Art I §1)

1. When Congress delegates quasi-legislative power – might be abdicating

responsibility to exercise powers its responsible for under Article I

ii. Congress can’t delegate adjudicatory powers to an agency so that it undermines the federal

courts’ authority to exercise “the judicial power of the US” – (Art III, §1)

1. When Congress delegates quasi-judicial power, worry it’s undermining powers

conferred on federal courts by Article III

iii. Contingency Doctrine: Executive isn’t legislating, just “filling in the details” and

implementing a certain group of principles based on the occurrence of a condition that

Congress wasn’t sure would happen

1. Article I: “All legislative power granted shall be vested in a Congress”

2. Courts must uphold statute unless unconstitutional (Marbury v. Mad.)

iv. Ensure an orderly government administration- Congress responsive to popular will

b. Formalist: Cannot delegate adjudicative or legislative power to an agency because delegated power

is “executive” not “legislative” - no difference in that power given to president or within the

executive branch

c. Functionalist: Rejects theory that delegated power is really the president’s - whoever got the

delegation has the power- decision-making now becomes subject to the APA or a sunshine statute

II.

Delegation of Legislative Authority

a. To what extent can you delegate to an agency legislative and adjudicative power?

i. Aggrandizement- When congress tries to have more control over agencies than what is

constitutionally allowable

ii. Encroachment- Congress tries to allocate duties and responsibilities in a way that appears to

violate a constitutional principle

b. Intelligible Principle Standard: So long as Congress lays down in legislation an intelligible principle

to which person authorized to exercise the delegated authority is can conform, such action is NOT a

forbidden delegation of legislative power (Misretta)

1. Found in the purpose section of organic statute OR can infer from other statutes OR

legislative history OR problem itself OR common sense

2. Usually Court Congress to give broad rulemaking power to agencies – can give

executive agencies power to take actions with legislative effects based on agency’s

policy judgments as long as Congress give them an overarching policy within which

to act (like “public interest”)

ii. Analysis: Look at procedural protections as much as substantive standards

1. Agencies may try and reduce necessary power delegated to them- cure vagueness by

adopting more procedural protection

2. Ex: FTC/FCC’s mandate is broad and vague, but so many procedural requirements,

it’s ok (want transparency, comments, etc.)

c. Goals: Reason for upholding broad delegations is pragmatic- more functional. Practical

understanding that “increasingly complex society . . . Congress simply cannot do its job absent an

ability to delegate power under broad general directives” (Misretta)

d. The Brig Aurora (1813): Statute authorizing Pres. revive statute giving favorable trading status to

France if Pres. felt countries were violating US neutral commerce

1. Usually delegate power to the head of a Cabinet or a free-standing agency who then

delegate to internal units (President has to ascertain a fact)

ii. Issue: Did the statute give the President too much legislative power by allowing him to decide

when the statute imposing the embargo would be suspended?

iii. Holding: No. The Court UPHELD presidential authorization to give favorable trading status

to countries if they were violating neutral commerce under the Contingency Doctrine:

President wasn’t legislating, just allowing previously enacted legislation to become effected

1. An area where the President has primary authority (dealing with foreign nations)

iv. Rule: If an intelligible principle principal is present then the delegated power is “executive”

not “legislative”

III.

e. Field v. Clark (1892): Tariff Act – normally requires duty free imports, but Pres. could suspend if

he felt that the other country was unfairly taxing US exports

1. The statutory delegation was to the President personally

ii. Rule: Congress can enact legislation the effect of which depends on the President’s

determination that a “named contingency” exists

iii. Holding: UPHELD the Act’s allowance of presidential suspension of duty free imports if

other country was unfairly taxing US import- It didn’t give president legislative powers,

because it only gave him discretionary powers to execute the law in a certain way based on the

occurrence of a specific condition

f. Waman: UPHELD Congress’ delegation of federal rules of process to SCOTUS – they are just

filling in the details (not a legislative function)

g. US v. Grimaud (1911): Conviction of people who grazed on public land, Congress had given

President power to make regulations to set aside land for public forest reserves

1. Statute didn’t let Secretary make rules “for any purpose,” but had to be rules to

insure that these reservations are preserved

ii. Holding: UPHELD Act- Difficult to separate legislative power to make laws from

administrative authority to make regulations BUT congress can give agencies power to “fill in

the details” without giving them actual legislative power

1. Expanded the Contingency Doctrine (Field, Brig) because here, the executive made

the rules, not just implementing rules made by Congress

h. J. W. Hampton v US: (1928): Tariff Act of 1922 allowed President to change statutory schedule of

tariffs on goods at President’s discretion if there was unequal exchange

i. (Taft): Congress cannot give up its legislative powers and give them to the President or

Judiciary, BUT the extent of the assistance one branch can give to another are fixed

“according to common sense and inherent necessities of the governmental coordination”

ii. Rule: As long as Congress gives out an “intelligible principle” by which a person authorized

to fix rates is directed to conform, its not a forbidden delegation of legislative power (president

only executes the law, he doesn’t make it)

iii. UPHELD- There was a sufficient intelligible principle for the agency to follow

Limitations on Delegation of Legislative Power:

a. Expansion of government during the passing of these two statutes before 2 cases

i. Government plagued by lack of transparency - where code was, when modified, etc.

ii. Court had tremendous hostility to dramatic expansive of federal regulatory authority wanted

opportunity to halt expansion (not have CFR, public comment, etc.)

b. Panama Refining v. Ryan (1935) (hot oil case): Statute allowed the President to regulate oil in

excess of state quotas by executive order – change pricing/stop allow oil transport

i. Holding: Court found that this was an INVALID, impermissible delegation to the executive

because there was NO intelligible principle for the President to follow, so President was

virtually legislating, so that isn’t allowed

1. Congress can’t assign this power to the President, because Legislature should

regulate IC commerce, and the 19 substantive standards were insufficient as an

“intelligible principle” – too much agency discretion

ii. Cardozo (dissent): Thought there was constitutional delegation- would have upheld

1. It shouldn’t matter the number of standards, because if there was a standard, and

president complied with one, that’s allowed

2. Banzhaf says that Cardozo is correct here- do have standards by which to guide

agency discretion to come into play

c. Schecter Poultry v. US (1935) (sick chicken case): Congress allowed Pres. to approve trade codes

for fair competition (submitted by industry) if certain elements met

i. Holding: Was an INVALID delegation- violated delegation doctrine – even though there were

standards, the standards weren’t well defined

ii. Hughes: There were no explicit guidelines, on how to define “fair competition,” – can’t

delegate to private groups an essential legislative function and there were no adequate

IV.

administrative procedures for the approval of the trading codes

1. Setting standards for industries was much more liberal than yes/no to oil transportleaves too much discretion to President to set standards

iii. (Cardozo): Unlike Panama Refining, where all Pres. is authorized to do is to prohibit

transportation, yes or no black/white- here he agreed with majority, said it violated delegation

doctrine because there was no limit to the president’s power here. Power was not “canalized”

but “unconfined and vagrant”

iv. Notes: If you have sufficient procedural protections, that may overcome vague and general

kind of delegation.

1. Ex: publish reasons for decision, have public comment period, etc.) (especially if

their substantive standard is “within the public interest” then significant procedural

protections)

d. Yakus v. US (1944): Congress authorized Administrator to promulgate regulations fixing “fair and

equitable prices” during war (court may have given agency additional “war power”)

i. Rule: Should only say its an impermissible delegation if its impossible to decide whether the

will of Congress has been followed or not

ii. Holding: UPHELD- There are enough details set out that we can determine what Congress

wanted – not too much discretion given to the agency here

iii. Might be moving from a formalist emphasis on separation of powers to a functionalist concern

with effective checks on delegated powers

iv. Purpose of Delegation Doctrine:

1. (1) Provide guidance to the agencies

2. (2) Provide for a substantive standard when agency’s actions are under review by

the courts (“intelligible principle”)

Functionalist Emphasis on Encroachment

a. Mistretta v. US: (1989): US sentencing commission- created federal crime penalties

i. Holding: UPHELD Congressional delegation to an agency set up in judicial branch because

there was a sufficient intelligible principle that the authority could use

ii. Blackmun: Functionalist: Separation of powers is flexible, no S of P violation here

1. Founders didn’t require that the branches be entirely separate and distinct, wanted to

focus on effective government (Jackson in Youngstown- “separateness but

interdependence, autonomy but reciprocity”)

iii. Different characteristics that should inform commission’s judgment for penalties- so better left

to a specialized body than the legislature

1. Ok to have some degree of comingling of functions, as long as there is no danger of

aggrandizement or encroachment of powers

b. Trucking I: American Trucking v. EPA (1999): DC Circuit Court of Appeals

i. CAA required EPA to set “primary standard” to protect public health with adequate margin of

safety, and a “secondary standard” to protect public welfare

ii. Holding: The court STRUCK DOWN for lack of an “intelligible principle” to use- “protect

public health” is too vague (what is the “requisite level of safety”?)

1. Like Benzene case: Could interpret statute to narrow what’s otherwise a more broad

authority

iii. The court wanted to give agency the opportunity to use an interpretation that doesn’t violate

the delegation doctrine SO court allowed the agency to adopt a more precise standard that

wouldn’t violate delegation doctrine

1. EPA needs to make a threshold finding setting how their standards were developedotherwise too much influence over American life without justification without any

constraints

2. Davis Principle- agency should adopt a more narrow construction

3. By supplementing substantive standard in the statute it cures problem.

c. Trucking II: American Trucking v. EPA (1999) DC Ct. Ap. Petition for Rehearing

i. EPA said that there was a limiting intelligible principle under the CAA

ii. The court followed Chevron instead of Industrial Union and deferred to the agency’s

reasonable interpretation of a statute of an ambiguous principle by which to guide its exercise

of delegated authority

1. BUT the “intelligible principle” itself was ambiguous, and not clear that the agency

applied the principle

d. Trucking III: Rehearing of American Trucking v. EPA (date?) Denying EPA’s Petition for

Rehearing En Banc

i. The court UPHOLDS finding that “requisite to protect public health” was enough of an

“intelligible principle”

ii. Constitutional avoidance canon used- APA should be used to limit EPA’s discretion under the

arbitrary and capricious standard

1. Davis’ Principle- agency can cure a weakness by coming up with an interpretation

of its own- but this was REJECTED

iii. The court said that it never suggested that an agency can cure an unconstitutional delegation of

power by making a limiting interpretation of the statute

e. Trucking IV: Whitman v. Trucking Association (2001): EPA has authority to set AAQS

i. Whether EPA has to look at costs of achieving an adequate standard of safety

ii. Scalia- Interpreted in its statutory and historical contact, §109 bars cost considerations for the

NAAQS setting processiii. Holding: Court UPHELD statute as delegation with sufficient “intelligible principle”

1. Provision requiring protection of public health granted EPA allowable discretion“well within the outer limits of the non-delegation precedent”

2. EPA made judgments, but that’s not conclusive for delegation purposes- EPA

wasn’t exercising legislative power, just implementing a statute

Notes: Don’t need intelligible principles to allow EPA to define “country elevators,” but would

need intelligible principle to allowed EPA to interpret “public health”

**Court hasn’t used delegation doctrine to invalidate a federal statute since 1936 (?), but has used

it to interpret a statute narrowly**

f.

Industrial Union v. API (Benzene case) (1980): OSHA directed agency to set safety standards

providing safe/ healthful place of employment using latest scientific knowledge

i. Holding: Plurality opinion STRUCK DOWN as potentially violating the delegation doctrine–

Court didn’t allow OSHA to interpret the statute so broadly

ii. Powell: Section 3(a) doesn’t preclude CBA, need to look at whether industry can bear costs of

reducing the safety standard – invalid how OSHA interpreted

1. Issue here is how to balance scientific harm against cost of compliance

iii. Stevens: Problem was delegation –Act requires Secretary to make threshold finding that the

working conditions are unsafe before implementing regulations

1. Like Schecter Poultry - no explicit guidelines, on defining “fair competition,” or

“safe” here- Congress probably didn’t intend to give Sec. power to determine what’s

“safe”

iv. Rehnquist: Said it violates the delegation doctrine –only justice to find that statute would be

invalid regardless of how interpreted

1. Benefits of Non-Delegation Doctrine (Locke)

2. (1) Provides recipient of any delegated authority an “intelligible principle” to guide

the exercise of the delegated discretion- guide agencies

3. (2) Courts reviewing the exercise of delegated legislative discretion must be able to

test them exercise against ascertainable standards- guide courts

4. (3) Ensures that important policy choices are made by Congress to be consistent

with orderly governmental administration- decisions aren’t made by politically

unresponsive agency- congress can’t “punt”

v. Notes: Maybe ultra vires- what is the scope of the power and how it was exercised?

1. Congress probably didn’t want to give Secretary power to create standards that

would have huge costs for the industry with little benefit to workers

a. Congress probably didn’t understand the implications of the determination

of whether something is a carcinogen

2. If the only limitation was feasibility, no CBA is required, then there is no safe lower

limit (down to zero), that’s a delegation issue

a. To save statute- plurality narrowed the statute by construction

b. New interpretation: the Sec has to make the determination that there is a

risk/something is unsafe, and since no decision was made, decision was

ultra vires

g. Chevron v. NRDC (1984): EPA’s CAA passed, different interpretations of “source” under Carter

and Reagan – DC Circuit said can’t change interpretation,

i. Holding: UPHELD as an agency reasonably interpreting statute

ii. Stevens: When a court reviews an agency’s construction of a statute it must ask:

1. (1) Did Congress speak directly to the precise question at issue? If YES, then the

Court should defer to Congress’ stance

2. (2) If NO, then ask if the agency’s construction of the section in question a

permissible interpretation of the statute?

iii. Rule: When a statute is ambiguous on the precise issue, a court should defer to a reasonable

interpretation of the statue by the agency responsible for administering it

1. Congress can decline to make basic issues, especially when its so technical that they

can’t do it, or if it’s too politically contentious to decide, want agency to do it- but

regardless of the reason, it’s allowed

2. If Congress has explicitly left a gap for the agency to fill, there is express delegation

of authority to the agency to elucidate a specific provision of the statute by

regulation.

iv. Notes: Holding is in contrast to Rehnquist’s belief that policy decisions should be made by

legislature not the courts

1. Very deferential. Dramatic contrast to the view of Rehnquist in Industrial Union

2. Where to put this – legislative delegation issue- but ultra vires?

V.

The Doctrine of Ultra Vires

a. Courts will strike down an agency action as utra vires (outside authority/beyond the power) if the

agency goes outside or beyond its delegation of power.

b. Congress could set broad policies in statutes, agencies could fill in details

i. If agencies were doing it wrong, congress could clarify

c. Direction: Court theoretically is working with Congress to prevent agencies from exercising a

power congress didn’t intend for them to have

d. Cure: Congress would have to amend the statute to cure ultra vires problem.

i. Ex: Regulate weather “within the public interest” (vague)

1. Cure: If we want agency to be able to do something, amend statute to give it greater

authority

e. Differences from Non-Delegation: Under delegation- court isn’t letting agency do what it wants

(cure with a substantive standard for an intelligible principle)

i. Working against Congress- Congress wants them to do something, but courts are limiting

agency’s authority

f. Similar to Non-Delegation Doctrine:

i. Working against Congress- Congress wants them to do something, but courts are limiting

agency’s authority

g. Example: Federal Hemline Commission

i. Statute to regulate “hemlines:” Can they regulate dresses or skirts, or is it ultra vires if

regulated pants

1. No idea as to purpose for statute- so don’t know if it should include pants

2. Meant for modesty or to keep women warm?

ii. Cure Ultra Vires: Could change to say “hemline including length of pants and suits”

iii. Cure Delegation Doctrine: Set an intelligible principle “regulate length of skirts to preserve

modesty” (reason for regulation)

VI.

State and Federal Delegation Doctrine:

a. Federal judges are more respectful of federal agencies, but there is less effective oversight from the

public and industry for state agencies

i. Judges are more wary of allowing federal agencies to act- more direct impact on daily life

(books in school, roads, zoning, etc.)

ii. Less publication, less public awareness about state agencies’ purpose

b. Boreali v. Axelrod (1987): Challenged NYC’s ban on smoking under the Public Health Law as too

vague, restricted smoking, but not in bars – no scientific expertise

i. Holding: NY Court of Appeals found it INVALID- no real reason why

1. Legislative function to balance competing health cost and privacy interests violated

the state-level non-delegation doctrine- exemptions for bars and at small restaurants

have no considerations of public health

ii. (1) Agency constructed a regulatory scheme with too many exceptions with social concerns

(carved out bars) (ULTRA VIRES?)

iii. (2) Agency didn’t just fill in the details, but created its own broad regulatory regime from a

blank slate (DELEGATION DOC?)

iv. (3) Agency exceeded scope of authority delegated to it- acted in an area where legislature

failed to come to an agreement- too controversial (ULTRA VIRES?)

1. Inferences from negative legislative action isn’t favored- can’t show what they

intended based on what they didn’t do

v. (4) No expertise was involved in the development of smoking regulation- just banned it

(DELEGATION DOC?)

1. Regulations might involve more common-sense than scientific – don’t always need

technical expertise

vi. Rule: Difficulty in getting legislation passed shouldn’t be a reason to defer it to the agenciespeople’s elected representatives should resolve difficult problems

Topic 3: Delegation of Regulatory Adjudication (Adjudicative Power)

I. Delegation of Adjudicative Power – 7th Amendment Issues

a. Article III of Constitution suggests problems with adjudicative authority in agencies

i. 6th Amendment: Criminal prosecutions get public trial by impartial jury

ii. 7th Amendment: Suits at common law, the right of trial by jury shall be preserved

iii. Statutes may be void for vagueness – this is the counterpart in adjudicative authority to the

intelligible principle doctrine with legislative authority

1. Cure a void for vagueness issue: Promulgate more specific regulations that clarify the

vague statute OR issue a “cease and desist” order, then that party then knows that he

has violated the vague statute and is on notice that if he continues violating action, he

will suffer the penalty

b. Old Standard: Divide all agency proceedings involving adjudication as either involving private

rights or public rights (Crowell)

i. Historically allowed delegation of adjudicatory power to non-Article III entities if it was a (1)

military court, (2) territorial court, or (3) tribunal for public rights (Northern Pipeline)

1. Public rights – Created by the statute - usually where the government is a party –

delegation of adjudication passes constitutional muster (claims people had against the

government, ok to be heard only by non-Article III courts because under doctrine of

sovereign immunity, didn’t have to allow them to be heard at all

2. Private rights – Individualized rights like contract law, but adjudication of private

rights usually created constitutional problems

c. New Standard: Look at whether delegation impairs either an individuals’ interest in having a claim

adjudicated by an impartial Article III judge or the structural interest in having an independent

judicial branch decide matters that have traditionally fallen within the core of Article III business.

(Schor factors) while also keeping in mind due process considerations requiring an Article III court

to play a role

d. Crowell v. Benson: (1932): Longshoreman Workers Act gave federal tort-substitute for injuries

i. Statute allowed the delegation of adjudicative power – courts had substantial reviewing power,

and the Act didn’t expressly preclude review by Article III courts

ii. Holding: Court UPHOLDS the delegation of adjudicative power over public rights to nonArticle III courts. Allowed judicial review of agency decisions for questions of law, but

limited authority to review questions of fact.

1. Reasons: (1) efficacy of the plan depends upon finality of determinations of fact, (2)

Plan provides for due process (notice, being heard, etc.), (3) And Article III courts

still get the final determination of non-jurisdictional facts.

iii. Rule: The doctrine of public rights vs. public rights used in Murray’s Lessee is no longer valid

because there is no requirement that determination of fact in constitutional courts shall be

made by judges (i.e. juries).

1. Looks to historic practice of courts of equity and admiralty – courts of equity allowed

non-article III courts to take part in some of proceeding (like fact-finding)

e. NRLB v. Jones & Laughlin: (1937)

i. 7th amendment jury trial right would rarely attach to typical regulatory programs

ii. Holding: 7th Amendment only applied to proceedings in the nature of a suit at common lawand National Labor Relations Act was unknown to common law

f. Curtis v. Loether: (1974): Fair housing provision of Civil Rights Act – right to jury trial?

i. Holding: Court found that 7th Amendment does apply to actions enforcing statutory rights if it

creates legal rights and remedies.

1. Congress can determine the primary statutory legal rights and remedies, and who can

enforce

ii. Rule: 7A generally inapplicable in administrative proceedings where jury trials would be

incompatible with whole concept of administrative adjudications and substantially interfere

with agency’s role in statutory scheme

g. Atlas Roofing v. OSHA: OSHA could give penalty upon finding of safety violation

i. White: When “public rights” are being determined, congress can decide that a jury forum

would be incompatible, can delegate adjudicative authority to agency

1. Ex: Government suing in its sovereign capacity to enforce a public right created by a

statute within the power of congress to enact

2. Private rights are sill reviewable by the courts and can have a jury- K, tort, etc.

ii. Holding: Violations requiring a civil penalty can be reviewable by the court system (like

public rights are reviewable by Article III Court), but findings of fact made by the ALJ are

conclusive if supported by evidence

iii. Rule: The 7th Amendment does not prohibit Congress from assigning fact-finding function to

administrative forum where jury would be incompatible – 7A is no bar to the creation of new

rights or their enforcement outside of regular court of law

1. Right to a jury trial turns not solely on nature of issue but the forum in which it is to

be resolved.

iv. Notes: Court still refers to distinction between private and public rights but the distinction

doesn’t work well – important to look at formalist/functionalist approach

1. When do they apply one approach over the other? No idea.

2. Formalism – Look at 4 corners of constitution/statute and don’t look beyond it to

decide constitutionality with no weighing or balancing. When court applies formalist

approach, it almost always strikes down.

3. Functionalist – Court looks beyond the words and look to balancing/reasonableness.

Much broader and more forgiving review.

h. Northern Pipeline v. Marathon: NP filed in Bankruptcy Court and sued Marathon on state-law K

claim – Act allowed bankruptcy court to decide state K claim with limited Article III court review

i. Holding: The Court INVALIDATED the bankruptcy courts’ acceptance of an unconstitutional

assignment of adjudicatory power to decide state K claim outside of Article III courts.

1. It is a necessary but not sufficient condition that the gov’t must be a party for public

rights – even though bankruptcy reorganization is a public right, state contract claims

are private rights, so legislative agency can’t hear it

a. Not an Article III judge, not a public right = strike it down

2. This is an extreme delegation of adjudicative powers to non-Article III judges – but

plurality opinion, so close to succeeding! (Plurality, so read narrowly)

ii. Rule: Congress can constitutionally assign cases of involving public rights to “legislative”

courts for resolution, but not state-law private right, contractual causes of action

1. Bankruptcy courts have too much power. District courts can appoint a special master

to conduct proceedings and make findings, but they are an adjunct. The bankruptcy

judges aren’t mere adjuncts for federal district courts

2. Bankruptcy judges lacked the protections afforded to Article III judges (life tenure,

secure pay), judicial power must be found in an independent judiciary – why aren’t

agency officials considered “independent judiciaries” – in other cases talk about how

they are assumed to have special unbiased judgments?

a. See C&W Fish v. Fox and Winthrow v. Larkin

iii. Approach: Plurality = Formalist: No balancing or weighing importance for delegating.

1. Rehnquist (concurrence): None of the cases has gone so far as to sanction the type of

adjudication in which Marathon will be subjected against.

2. White (dissent): Functionalist approach. Constitutional values should be balanced

against legislative responsibilities - the presence of judicial review and absence of

high political interest insure that Bankruptcy Court wouldn’t weaken the judiciary.

i.

Thomas v. Union Carbide: FIFRA permitted EPA to use one manufacturer’s data about effects of

its product in considering another manufacturer’s later application.

1. Act provided for binding arbitration if parties couldn’t agree on the amount and

limited, but didn’t preclude Article III review of arbitration proceeding

ii. Holding: Thomas: Court UPHELD Act: Licensing provision creates the relationship between

the data submitter and later registrant, and federal law supplies rule of decision.

1. Repudiates the Northern Pipeline public/private distinction definition

iii. Rule: Congress can create a seemingly “private” right that is so closely integrated into a public

regulatory scheme as to be a matter appropriate for agency resolution with limited

involvement by the Article III judiciary

iv. Approach: Functionalist: Focus on purpose served by statutory delegation of adjudicatory

power and impact of delegation in “independent role of judiciary in constitutional scheme,”

rather than doctrinaire reliance on formal categories.

1. Purpose of the legislation must be weighed against the intrusion of the right and

when that balancing is done, there is little encroachment on Article III powers

v. Factors Considered: (1) Manufacturers’ rights in their data were more fitting of public right

with a public purpose (safeguard public health, instead of a purely private right- created by

statute not common law), (2) Arbiter is selected by agreement of parties or appointed on a

case-by-case basis by an independent federal agency (free from political influence), (3) Act

does not preclude judicial review even though review was limited

j.

CFTC v. Schor: Trading through broker at CFTC-regulated firm, Shor filed administrative

complaint under Commodity Exchange Act, Broker counterclaimed alleging violation of CEA

i. Issue: Can Congress allow the Commission to adjudicate compulsory counterclaims?

1. Counterclaims were like those that non-article III bankruptcy judges were unable to

adjudicate under Northern Pipeline

ii. Holding: O’Connor: Yes. Court UPHELD Act– Commission can hear broker’s counterclaims

without violating Article III

iii. Rule: Constitutionality of a congressional delegation of adjudicative functions to a non-Article

III body must be assessed by reference to purposes underlying Article III requirements–

Courts should not rely solely on the language of the Constitution.

1. Functionalist: Want to (1) Structural: Protect the role of an independent judiciary

and (2) Personal: Safeguard litigants’ right to have claims decided before judges who

are free from potential influence by other branches

a. Litigant waived his right to an independent judiciary by counterclaiming in

the administrative hearing

b. More efficient to have the permissible counterclaims adjudicated with the

main claim, the actual claim heard is a very small part of judicial business

and the decisions were subject to judicial review

2. Balance: (1) Whether the essential attributes of judicial power are reserved to Article

III courts, (2) The extent to which the Non-Article III forum exercises range of

jurisdiction/powers normally vested in Article III courts, (4) Origins and importance

of right to be adjudicated, (5) Concerns that drove congress to depart from

requirements of Article III.

iv. Notes: Difference between Crowell: CFTC only deals with a “particularized area of the law, in

contrast, the bankruptcy courts extended to broadly “all civil proceedings arising under cases

related to cases under title 11 (more efficient to hear counterclaim here than new case)

1. CFTC orders are only enforceable by order of the district court

2. CFTC orders are reviewed under the same “weight of the evidence” standard under

Crowell, not the “clearly erroneous” standard of Northern Pipeline

3. BUT is a private right, so look more closely- Congress has given only limited CFTC

jurisdiction over narrow class of common law claims and unchallenged adjudicative

function doesn’t create a S of P threat

k. Granfinancera: Plaintiff’s 7A rights were violated by refusing a right to a jury trial for a claim to

recover money fraudulently transferred by the bankrupt party

i. Holding: Brennan: INVALIDATED refusal of jury: D had right to jury because the claim was

legal not equitable – recovering money transfer was a private right.

1. Was a private right because it was neither a (1) public right nor a (2) private right so

closely intertwined with a public regulatory program (like Union Carbide FIFRA

case)

ii. Rule: Test: Did congress, acting for a valid legislative purpose create a seemingly private right

that is so closely integrated into a public regulatory scheme that it’s appropriate for agency

resolution with limited involvement by Article III courts? Not here! Congress can only deny

trials by jury in actions at law in cases where “public rights” are litigated

iii. Approach: Functionalist – federal government doesn’t have to be a party for a case to revolve

around “public rights” – diverged from Northern Pipeline holding that government as a party

is necessary but not sufficient for a public right

iv. Scalia (dissent): Public rights must be only between government and others

1. Advocated a formalist approach

l. Stern v. Marshall (2011): Anna Nicole Smith case – bankruptcy issue

i. Holding: Even though bankruptcy court had statutory authority to enter judgment on core

counterclaim, it lacked the constitutional authority to do so under Article III.

1. Bankruptcy court wasn’t subject to the constitutional assurances of independence

which would allow adjudication of debtor’s state law claim

ii. Rule: Bankruptcy court cannot enter final judgment on the counterclaim even though the

statute attempts to distinguish between the core functions and non-core functions where this

would purportedly be permissible

iii. Notes: Question: How far can we go in terms of turning things which are handled by courts

over to agencies?

iv. Experts say – this is a relatively narrow holding in an unusual case because state law

counterclaims are not frequent

1. But – fair reading of plurality and concurring opinion points to an extension of the

Stern holding that would prevent Bankruptcy Court from entering final judgments on

certain other claims

2. No clear limits have emerged because of these obscure Court opinions.

Topic 4: Congressional and Presidential Impact (Appointment & Removal)

I.

Congressional & Presidential Regulatory Outcomes: Appointment & Removal

a. Three Branches: Article I – Legislative, Article II – Executive, Article III – Judicial

b. Article III, §2, cl. 2: “The President . . . shall nominate, and by and with the advice and consent of

the senate, shall appoint officers of the US . . . but Congress may by law vest the appointment of

such inferior officers as they think proper in the President alone, in the courts of law or in the heads

of departments”

i. Appointments clause doesn’t give Congress power to appoint “officers of US”

c. Invalid Congressional control of administrative agencies:

i. (1) Appointing administrative officials (like Buckley), (2) Having members of Congress serve

on administrative bodies (like Metro Washington Airports), (3) controlling removal of

administrative officials (like Bowsher), (4) by exercising a legislative veto over administrative

action (like Chada), and (5) oversight power.

d. Framers didn’t want Congress to have the power to create agencies and then fill them too

II.

Congressional Control Over Agency Action

a. INS v. Chada (1983) Student from US, tried to get deported –Immigration & Naturalization Act

said either house could veto AG’s order that Chada stay

i. Deportation could be reinstated if a house of congress disagreed with INS ruling

ii. Background: Congress wanted to delegate powers to president, but reluctant to give that

power up, so gave executive power, but reserved the right to overrule executive decision

(discussion of APA amendment to make legislative reviews generic)

1. Presentment: Article 1, §7: Present legislation to Pres. before adoption

2. Bicameralism: Article 1, §1&7: No law could take effect without the concurrence of

the prescribed majority of the members of both houses

iii. Holding: Burger: Legislative veto provision of Act allowing a one-house veto over executive

orders was UNCONSTITUTIONAL – action wasn’t within any of the express constitutional

exceptions authorizing one House to act, and as an exercise of legislative power, it was subject

to Article I requirements

1. Appropriate body to deal with rights is the judiciary, not the legislature

2. House’s disapproval had the purpose and effect of altering the legal rights, duties and

relations of persons outside the legislative branch

iv. Approach: Formalist: Need stronger division between executive and legislative

1. Efficiency of government is not the goal- presumption of constitutionality

2. Need presentment and bicameralism if actions are “properly regarded as legislative in

character and effect”

v. Powell (concurring): This invalidates all legislative vetoes- frequently used historically – the

Court should have decided the case on narrower grounds

vi. White (dissenting): Bad to take away legislative veto- congress has to make laws all very

specific now, or leave all lawmaking to the executive and independent agencies

1. Legislative veto was a democratic tool used to keep government structure in check

without overburdening congress – functionalist approach

vii. Notes: Very broad opinion, usually courts shy away from a constitutional argument, or make a

narrow holding – but here the decision impacted many statutes

1. Maybe SCOTUS wanted to discourage Congress from expanding this legislative veto

into the APA

2. Many of these statutes still exist because people lack standing to challenge

b. Bowsher v. Synar: OMB/CBO were to independently estimate federal deficit, and tell Comptroller

General, who was to identify cuts needed deficit exceeded statutory limits

1. Congressional Budget Office (Article I), OMB (Article II) – wanted to insulate

Comptroller from special interest groups due to the importance of their decisions so

had budget cutting authority as executive, with the Comptroller removable by

congress

ii. Holding: Burger: INVALID- Congress encroached on the power of the executive by vesting

executive functions in the Comptroller, who is answerable to Congress

iii. Approach: Formalist - Congress wanted Comptroller as an officer of legislative branch, but

tasked with executing the laws (executive) so Congress is intruding on executive function (like

Chada)

iv. Rule: Congress can’t reserve for itself the power of removal of an officer charged with

execution of the laws except by impeachment

1. Congress can’t have control over the execution of the laws because that would

essentially give Congress control over execution of laws through veto power by

removing officer who didn’t execute the laws correctly

v. White (dissent): No actual threat to separation of powers (functionalist approach)

1. Congress can’t reserve an executive role for itself or its agencies, but removal of

Comptroller isn’t a Congressional execution of the laws- the statute articulated the

limited job of the agency

vi. Blackmun (dissent): If Congress attempts to remove him improperly, then it would be S of P

issue, but should be allowed to have Comptroller until then- functionalist

vii. Notes: Congress can only act through legislating – can’t do indirectly what they can’t do

directly (Chada applies to independent agencies)

c. Buckley v. Valeo: Federal Election Act tried to set campaign finance reform

i. Holding: Court found statue authorizing Congress to appoint officials to serve on Federal

Election Commission an INVALID violation of Article II

1. These congressional leaders weren’t within the “courts of Law or “heads of

Department” that the Constitution said Congress could appoint

ii. Rule: Congress CANNOT appoint an officer of the US besides those officers authorized by

Article I to assist in the legislative process

d. Metropolitan Washington Airports v. Citizens (1991): Federal airports transferred to Commission

operated by VA, MD and DC, Act gave Review Board right to veto Commission’s decisions, but

Review Board as made up of Congressmen

i. Holding: Stevens: Court found Act INVALID because Congress can’t vest in itself agents

with executive power

1. If they were being executive, can’t do that because Congress isn’t executive AND if

they were being legislative, can’t do that because violates Article 1 Section 7

(bicameralism & presentment)

ii. On Remand: Didn’t put Congressmen on the Review Board, but put individuals who are

registered voters not in DC, MD or VA, and are on lists of candidates supplied to Commission

by House and Senate

1. DC circuit struck down and SCOTUS refused to hear it again

III.

Presidential Control Over Agency Actions: Appointment

a. Article II allows president to appoint “Officers of the US” with advice and consent of senate

i. Congress can invest power to appoint “Inferior officers” in the President, Courts of law, or

heads of departments”

b. Morrison v. Olson (1988) Superfund law, DOJ’s OGC may have given false testimony, Morrison

appointed as special investigatory counsel, served subpoenas

i. If certain criteria are met, AG must call judges of the Special Court who must appoint an

independent counsel, who could be removed for “good cause/disability”

ii. Holding: Rehnquist: Since the Independent Counsel was an inferior officer, the inter-branch

appointment was permissible unless it impaired the ability of the Executive Branch to perform

its functions - “good cause” removal provisions don’t impermissibly undermine or impede on

the executive branch functioning

1. Does NOT disrupt the proper balance between the branches

iii. Approach: Functionalist- Allow appointment of prosecutors in judiciary contempt cases,

(policy reasons)

iv. Test for finding whether legislation is an impermissible intrusion on S of P: (Morrison v.

Olson)

1. Does it limit his ability to “take care” and faithfully execute the laws?

2. Does it impede his constitutional duties?

3. Does he still have effective control over the executive branch?

v. RULE: No violation of the separation of powers by increasing the power of one branch at the

expense of another. Grounds for finding that she is an inferior, not a principle officer, so no

violation of the appointments clause (is she subordinate/independent, scope of jurisdiction,

extent of duties)

1. Ability to remove someone at will isn’t imperative to carrying out executive

functions (different than Weiner and Buckley principle)

2. Subject to removal by a higher executive official (AG), only performed limited duties

(only one task), no policy making duty

3. Court can terminate to be used narrowly when task is virtually completed

(functional)

vi. Scalia (dissenting): Law has to be struck down because (1) Criminal prosecution is an exercise

of "purely executive power" as guaranteed in the Constitution and, (2) the law deprived the

president of "exclusive control" of that power (Congress can’t qualify by adding limits to that

exclusive control)

1. Two checks against abuses of power, can impeach a person who impedes

investigations, and political check, remove president at next election

vii. Notes: Should have independent counsel investigating executive wrongdoing

1. Most people think it falls under Myers, not Humphreys, but Rehnquist thinks its more

like Humphreys, but establishes a different test

c. Freytag v. Commissioner of IRS (1991): Whether Tax Court (Article I, leg) qualifies as a

department or a court of law (can special trial judges be appointed by the chief judge?)

i. Rule: Tax Court judges are inferior officers, BUT Department is only a division of the

executive branch - But Tax courts are courts of law for appointments purposes

1. Don’t want to let the power to appoint be a way to decrease public accountability

ii. Holding: Blackmun: Allowed even though Tax Courts are within the legislature (Article I),

court of law, because the court makes adjudicative decisions

1. BUT then how do the freestanding or independent agencies fit?

2. Limiting definition of “Department”

3. “Inferior Officers” includes special trial judges on US tax court – president can

appoint them if Congress vests power in President instead of “Courts of Law”

iii. Free Enterprise- Adopted reasoning of “self-contained entities in executive “branch” where

class of duties are allotted to a particular person

d. Edmund v. US (1997): Military judges have neither limited jurisdiction nor limited tenure – Court

found them to be “inferior officers” (other factors for determining inferior than Morrison)

i. No power to issue final decisions unless permitted by superiors, who were appointed

ii. Inferior/Superior: Inferior if you have a superior/have a relationship with a higher ranking

officer below the President, have work which is directly supervised at some level by a person

who is appointed by the president and confirmed by the senate

iii. Officers or Not: Whether they exercise significant authority over the laws of the US (Case)

e. Misretta v. United States: President appointed members to Sentencing Commission, approved by

senate, 3 of 7 are federal judges – attorney general is non-voting member

i. Holding: Blackmun: Court UPHELD Sentencing Commission act. The vesting of nonadjudicatory activities in the judicial branch DOES NOT violate S of P

ii. Approach: Functionalist: Separation of Powers not violated with an independent commission

in judicial branch – flexible, and practical approach used here

1. Commission is not controlled or accountable to the judicial branch, doesn’t add to

judicial branch powers, Commission has no judicial authority

2. Delegation doctrine: had guidelines and protocols, so clear about what congress

wanted- delegation doctrine was probably not violated

3. Not too political (which would be executive), not beyond their expertise (not

deciding foreign policy)

4. Executive and legislative branches voted for it (ok here, but argument didn’t work in

Chada or Bowsher)

iii. Test: Does the extrajudicial assignment undermine the integrity of the judicial branch? NoThe commission is only focusing on the development of rules, not sharing judicial powers in

decision-making

iv. Scalia (dissent)- Constitution not a suggestion, but a structure to be followed closely

f. Intercollegiate Broadcasting v. Copyright (2012): Copyright Royalty Judges issued a final

determination adopting royalty structure

i. Holding: Court INVALIDATED Act for appointments clause violation. CRJ’s were principal

officers who had to be appointed by president and confirmed by the Senate

1. Can’t have principal officers who are able to be removed by Librarian of Congress,

so remedy by changing Judges to be “inferior officers”

ii. Inferior or Superior? Have little substantive oversight, librarian can only remove for cause,

rate determinations weren’t reviewed or corrected by any other officer within the executive

branch – so they were probably superior officers – but changed status

1. Ratemaking has huge control over the industry, so need to make sure constitutional

appointment and supervision of authority

IV.

Presidential Control Over Agency Actions: Removal

a. Court allowed “for cause” removal power whether or not person was purely executive or quasijudicial/legislative – turned on impediment to executive functioning in Morrison

i. Court now takes a functional approach in reviewing congressional restrictions on President’s

removal of officials (1) What type of function do they exercise? (2) Are they a principal or

inferior officer? (Morrison))

b. Myers v. US: Postmaster General fired Postmaster of Oregon before end of 4-year term

i. Postmaster and cabinet members serve under a Tenure of Office Act

ii. Holding: Taft: Court UPHELD presidential authority to remove postmaster even though his

statutory term was longer (Postmaster is purely executive)

iii. Rule: The power to remove inferior executive offers, like that for superior executive officers,

is incident of the power to appoint them, and is in its nature an executive power

1. Congress can’t participate in the exercise of executive power

iv. Holding: President has exclusive power to remove executive branch officials whose functions

are purely executive- doesn’t need approval of Senate or other legislative body

1. (Dissent): Prescribing conditions under which an officer can be removed is a

legislative duty

2. (Dissent): Myers was an inferior officer, so should follow other rules about

discharging him

c. Humphreys Executor: FDR tried to remove FTC commissioner before his tenure was up

1. FTC commissioner made investigations and reports to Congress, and proposed

judicial decrees for the courts, so both quasi-judicial and legislative

ii. Holding: Court INVALIDATED removal. Congressional intent was to create body

independent of executive authority, except in selection – Commissioner was quasi-x

1. Congress can make place limitations on heads of independent agencies to dismissal

for things like “for cause” to insulate from political pressure

2. Coercive power of removal threatens independence of commission, plus Commission

had a very limited role, limited power

iii. RULE: If the officer is quasi-legislative or quasi-judicial, and not purely executive, then

separation of powers prevents placing an unlimited power of removal in Pres.

d. Weiner Case: Since president couldn’t dictate the outcome directly, he couldn’t do so indirectly by

having the power over their firing

i. Holding: Commissioner who was wrongfully removed could be sued for back pay

1. Didn’t decide if he could get job back –even if they get back pay, Pres. could violate

and fire

ii. Rule: No express provision that someone could be fired without cause, but Court found it

implied in statue because the agency exercised quasi-adjudicative powers

e. Sierra Club v. Costle (1981): EPA issued new sulfur emission standards, lower standard would

have been hard for economic stability (opposed by Senator Byrd and Pres. Carter)

1. Proposed draft rules, written comments, documents and written responses from

interagency review process during rulemaking should be in the docket

ii. Holding: It WAS NOT necessary for due process to docket a face-to-face policy session

between EPA officials and the President after the comment period because the rule wasn’t

based on any information arising from that meeting.

1. Don’t need to document every single rulemaking session

2. How is this an appointment/removal power issue? Isn’t it due process?

f. Portland Audubon v. Endangered Species Committee (1993): Litigation about timber sales in the

habitat of northern spotted owl: ESA’s 7 member committee can authorize exemptions from Act

during on-the-record hearing before ALJ and report by Sec of DOI

1. Section 557(d) prohibits ex parte communication between an agency decisionmaking member, and an “interested person” outside the agency

2. Numerous “off the record” meetings between white house and agency

ii. Holding: The committee’s proceedings are subject to the ex parte communications ban, and

POTUS is an “interested person” under the Act, so his communications are covered by the

provision

1. The Committee’s decisions are “quasi-judicial” so are adjudications under the section

- even though President appointed commission members, can’t dictate an outcome

iii. Congress hasn’t invaded any legitimate constitutional power of President in forbidding him to

attempt to influence a Committee decision – if President could influence decision, would

destroy the integrity of all federal agency determinations

iv. Rule: When an agency performs a quasi-judicial/legislative function, its independence must be

protected

1. President is not “an agency” and if he was, his actions would be reviewable by the

judiciary under an abuse of discretion standard

g. Free Enterprise Board v. PCAOB (2010): PCAOB members can be removed for “good cause” by

SEC Commission, and Commission can be removed by pres. for inefficiency, duty neglect,

malfeasance (multilevel protection from removal for PCAOB members)

i. Holding: Roberts: Court INVALIDATED Act, but allowed Board to continue its duties – the

removal process was contrary to Article II’s vesting clause – Act denied the President the right

to remove inferior officers directly

1. Decision of whether “good cause” exists isn’t with the president, but in the

Commissioners, who aren’t under direct Presidential control

ii. Approach: Formalist: Diffusion of powers is a diffusion of accountability

1. Board members are inferior officers whose appointment congress may permissibly

vest in a “Head of Department,” but President can’t here hold his subordinates

accountable, so his execution of the laws is impaired

2. Rejects Freitag – doesn’t worry about “Department” definition distinction

iii. Bryer (dissent): No S of P issues- doesn’t interfere with President’s executive power

V.

Presidential Direction of Regulatory Outcomes

a. Delegation: Statutes usually delegate decisional authority to a named federal official (Cabinet

Secretary, Administrator, head of a Commission, etc.) instead of the president

i. Stages of Regulatory Activity: (1) Agenda-setting, (2) Negotiation of Standards, (3)

Implementation, (4) Monitoring, (5) Enforcement

ii. Methods of Influence: Clinton was able to influence/dictate the content of agency rulemakings

and policy making (formal executive memoranda to executive agency heads, Bush had

“signing statements” when signing a statute into law

1. Influence by fear of his removal power, and his help in budgetary maters

2. Courts don’t pay attention to signing statements- little increase in authority re

Congress, but most authority still comes from his saying how statutes should be

interpreted and which ones are on his priority lists

iii. Increasing Politicization: Number of political appointees not stable, varied across agencies and

time with how close agency’s policy views were perceived to be aligned with the Agency’s

1. Issues with loyalty, trust and competence in agencies between career and political

appointees - need intra-agency checks and balances- make sure people on the inside

have long-term knowledge and no conflicts of interest like political’s might have

(close ties to industry after administration’s end)

iv. Obama Administration: Disavowed signing statements, but then used, appointed policy special

advisors/czars

1. But no real formal authority- can’t control budgets, hire or fire or promulgate

regulations – just powerful people influencing others

2. Czars make cabinet secretaries middle managers – disrupt executive power flow (plus

Czars have no accountability to Congress/voters)

b. Legal Basis for Presidential Directory:

i. Little Judicial Review: President’s directory authority has had little judicial review

1. Marbury v. Madison: President should use his discretion, accountable to his country,

political character, and his conscience

a. No review of executive officers except by President

2. Myers v. US: Even presidential power to remove doesn’t equate with power to direct

particular regulatory outcomes

3. Youngstown:

ii. “Take Care” Clause: President has authority to execute laws (even those that mention

Secretary as head) because President has power to execute all federal laws

1. Need a strong unitary executive to ensure effective governance

iii. General Deference: Deference among executive officials to presidents opinion –need

presidential oversight/ directory to make regulation democratically accountable

1. Maybe president has more oversight over everything- but can’t dictate outcomes?

Oversight as different from accountability

2. Accountability vests ultimate decisional authority in a person who is elected

(President is most accountable)

VI.

3. Popular control keeps check on unitary executive from becoming a dictatorship –

don’t want public power to be seized by private interests

Law & Economic Discussion

a. Libertarian Paternalism- Making it harder to do something, but not prohibiting it

i. Behavioral regulatory approach that manipulates how choices are framed to consumers

(Volokh Law Website- says L.P. will fail)

1. Ex: Soda size limitations, but can buy as many as you want

ii. Way of presenting alternatives - Nudge principle

1. Ex: check box to sign up or check box to opt out of Retirement Plan

iii. Change is designed to benefit your own welfare

b. Behavioral Economics: Econ & psychology shows that people are not always rational – risk

adverse, ex: lottery tickets

c. Veblen Goods: Theory of the Leisure Class (price goes up, you buy more- status)

d. Banzhaf: Favors government intervention in some circumstances

Topic 5: Other Legislative & Administrative Controls

I. Congressional Direction: Appropriations & Spending

a. Legislative Influence on Agencies:

i. Standing Committees: Oversight, hearings are designed to increase agency pressure, threats

of investigation

ii. Appropriations/Funding: Determine agency funding, not only x amount, but dictate what to

spend it in (limitations and riders)

1. Legislative bodies write laws which impact executive agencies

a. Can put riders in appropriations bills (“and no portion of this appropriation

shall be used for ___”)

2. Funds can be authorized in the legislation, but then have to be appropriated

3. Legality: No SC case has addressed whether appropriations directing agencies to act

or not unconstitutionally infringes upon president’s authority

4. Limitation rider- says that agency can’t spend any of the appropriated money to

engage in a specific activity

a. Used to prohibit finalization of particular proposed rules

b. Prohibits the development of regulations on particular statues or issues

c. Limitation riders help congressional majorities more under divided

government than under a unified government

5. Allowed as “spending retrenchments,” don’t require orders from House Rules

Committee to reach the floor, less Presidential ability to remove individual riders

6. Agencies can work around appropriations limitation – might issue a guidance

document instead of a regulation or another agency with overlapping statutory

authority might take the responsibility

7. Substantive riders- Impel (or impede) regulatory action (“can’t use this to pay for a

salary if that person will prohibit the enforcement of x”)

8. Presidential “impoundment” or refusal to spend money for certain activities

9. Programmatic impoundments- if money no longer needed, no mandate to spend it

iii. Congressional Review Act:

iv. Agency Proceedings: Legislature can participate in agency proceedings

1. Rulemaking: No limits on Congressional ability to submit proposals for rulemaking

or comments on existing rulemaking proceedings

2. Adjudicatory: Congress can initiate and participate in many agency proceedings (but

some limitations)

b. Executive Influence on Dependent Agencies:

i. Califano from HEW (not HHS): Hard to get agencies to operate

1. Political’s or career people might be resistant to change

ii. Harder to inject new ideas into agencies – hard to implement new strategies because of

bureaucratic inertia (but more stability?)

c. Executive Influence on Independent Agencies:

i. Harder to influence an independent agency, but possible.

ii. Budget Control: OMB of executive branch controls agency budget requests

iii. Litigation: Question of legal defenses in defense of an Agency is made by DOJ/ executive

branch, not by the agency (including settlement agreements)

iv. FOIA: Information requests go through executive branch agency – may influence response

v. Signing Statements: Used by president when legislation passed, often in relation to agencies

(not a veto, but not an endorsement)

vi. Impoundment: President can impound various funds

vii. Czars: Ability to appoint czar has persuasive power, but how does that impact agencies?

viii. Limitations: Limits on removal power - FTC Chairman: Paul Randixon: President asked him

to leave for new administration, but refused to leave office

1. Can’t fire Commissioners if the have a term limit EXCEPT for cause

2. Difficult to determine what is “cause” and how established

3. Most employees are protected by civil service

b. Other Influences on Agencies:

i. Industry - if regulatory agency deals with a small industry/smaller interest groups

1. FDA has close ties with drug companies/ FCC and Broadcasters

ii. Media has large influence on agencies – different today (blog/twitter)

1. Peace symbol, front page of Washington Post, trademark case shut down application

iii. Public Interest Organizations also influence

Topic 6: Methods of Obtaining Judicial Review (Damages)

II. Methods of Obtaining Judicial Review, Damages Actions, Suing States

a. Specific Relief: Injunctions, Declarations & the Prerogative Writs

i. Banzhaf: Favors more expansive judicial review, narrower reading of doctrines intended to

prevent judicial review (mootness, standing, etc.)

ii. More review creates more agency expense, harms public interests, adds to delay of agency

actions, weaken agency action

b. Historical Judicial Review:

i. Judicial Review in France: Had to bring a common-law cause of action (strong presumption

against judicial review)

1. Agencies treated like people – charge with conversion for tax issues

c. Means of Getting Judicial Review of Agency Decisions:

i. APA is not a source of jurisdiction, then frame action (not like a common law) but within

boundaries of APA

1. But 28 USC §1331 – federal question statute – provides jurisdiction for suits in

federal district courts raising questions under federal law

2. Or under the specific statute – details review by a court of appeals (usually)

a. But what if the organic statute doesn’t make its statutory jurisdiction

exclusive – can they use either that statute or 1331 or something else?

b. What about if they’re raising a claim not exactly within the provision

allowing judicial review?

i. Might allow suits failure to act under that specific portion

ii. Issues: Sometimes not clear which court to go to because statute may not be as clear about

where to review (if file in wrong court, issues with Statute of Limitations if refilling)

iii. Specific Statutory Review: A statute sets process for judicial review

1. As long as your situation falls within the statutory requirements, you get the review

2. Ex: FTC says “person ordered to cease and desist from unfair trade practice may

seek judicial review of a final order by filing in US court of appeals”

3. Normally in Court of Appeals – appeal from an agency decisions is similar to an

appeal from lower court (petition for review)

iv. General Statutory Review:

1. Ex: Same FTC, but want to appeal something that isn’t a “final” order – doesn’t fit

in specific statutory framework

a. TRAC: Where a statute says final action reviewed in court of appeals, bring

all actions in court of appeals because otherwise might affect future statutory

powers to review decisions {hard to know what fits in this rule}

2. Normally but NOT always in District Court – need jurisdiction

a. Still have to find jurisdiction and a cause of action

v. Non-Statutory Review:

1. Federal courts only have jurisdiction given to them by statute (§1337: commerce,

§1342: deprivation of constitutional rights by state officials, or §1331: federal

question, §133x: diversity), so have to give the courts that statutory jurisdiction

2. Have to use historical writs, etc. because no particular statue

a. Ex: Equitable maxims

3. Issues: Injunction, writs are remedies, not causes of action

a. Sometimes in district court, or force agency to go to court

d. Prerogative Writs: Originate in British law (common law), equitable rights with equitable relief

i. Most equitable rights or actions come with equitable maxims

1. May have a legal right, but if relief you want violates an equitable action, can be

denied remedy (“Equity won’t reward dirty hands, etc.”)

ii. Certiorari: Order by a higher court directing a lower court to send the record in a given case

for review – like SCOTUS petitions

iii. Habeas Corpus: Challenging validity of holding person; demands that a prisoner be taken

before the court to determine whether there is lawful authority to detain the person

iv. Mandamus: Remedy/Order issued by higher court used to compel or to direct a lower court

or a government officer to perform ministerial/non-discretionary duty (ex: license)

1. But limited, because few governmental duties are purely non-discretionary

2. If an official goes beyond his discretion: Can still seek a remedy in the nature of

mandamus to compel them to stay within ‘zone of discretion’

a. 28 U.S.C. §1361: “District courts shall have original jurisdiction of any

action in the nature of mandamus to compel an officer or of the US or any

agency thereof to perform a duty owed to the P”

b. Ex: 20 years of fireman service, right to retire and get pension

i. Pension Board said no, court declined to consider the order because

would “Let a Public Mischief” which was an equitable doctrine

v. Prohibition: Directing a subordinate to stop doing something the law prohibits;

vi. Procedendo: Sends a case from an appellate court to a lower court with an order to proceed

to judgment;

vii. Quo Warranto: Requiring a person to show by what authority they have to hold

office/exercise a power;

viii. In Re: An action brought on behalf of something which is not properly able to represent itself

(historically wives had no legal capacity so, sued on their behalf)

1. Bribes MD Governor/VP: Guilty, but not required to give $ back

a. GW Students brought suit: Agent and principle- if someone bribes an agent,

then the principle has a cause of action against the principle to recover the

funds

b. Qui Tam- Can recover from an injury for a person who is dispossessed and

not able to bring the action

ix. Writs all impact agency behavior and policy (unlike damages which is just $$)

1. Not really a suit against the sovereign because sovereign didn’t order its agents to

violate the law (certain relief is codified- determines what rights you can seek)

e. Damages: Good option- “sue the bastards” if you have a tort claim – less issue with standing and

cause of action because more explicit

1. Sue agency or the individual – more likely to have impact on agency action

2. Contingency fee- so makes it easier for poor people to sue

3. If agency action injured a private party, could sue in tort or contract for damages

ii. Tort Action: Sue agency or the individual – more likely to have impact on agency action

1. Contingency fee- so makes it easier for poor people to sue

2. No need for new common law theory, don’t have to worry about standing, because

you got tort-ed AND it’s a good way to deter government repeating mistakes - $$

3. Banzhaf loves tort actions – “most effective way of getting judicial review of

agency actions because potential for assessing real and substantial damages”

(sometimes punitive) both against governmental official and governmental unit

4. Limitations: Sometimes agency did wrong, but didn’t commit a tort, but strong