James Bradley essay with references

advertisement

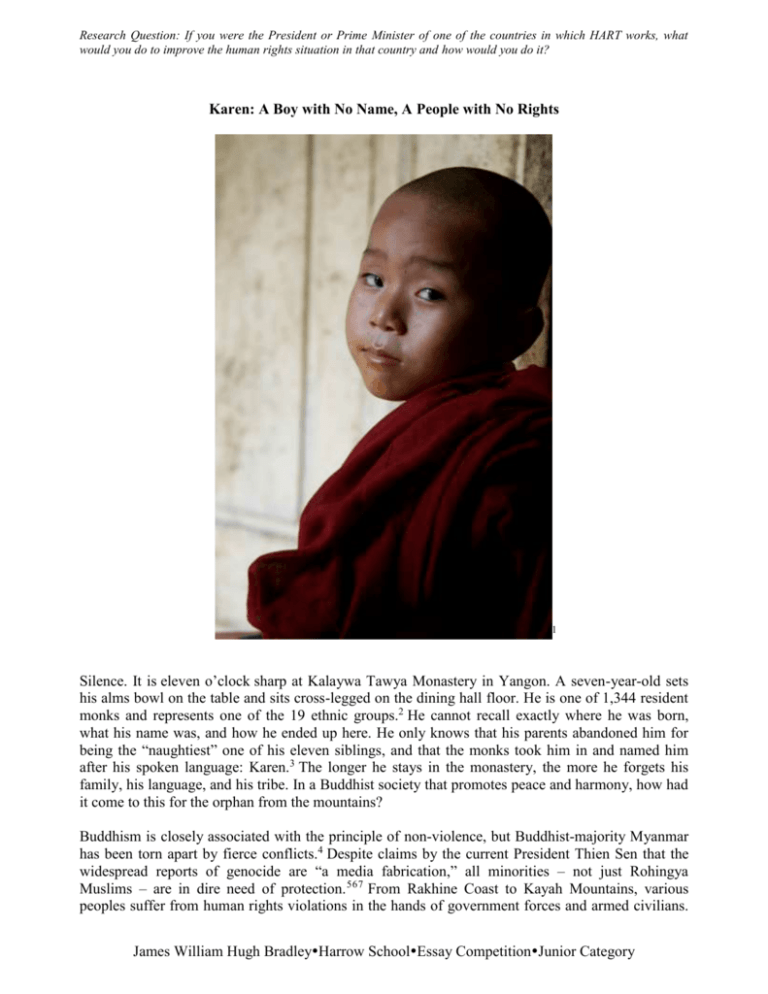

Research Question: If you were the President or Prime Minister of one of the countries in which HART works, what would you do to improve the human rights situation in that country and how would you do it? Karen: A Boy with No Name, A People with No Rights 1 Silence. It is eleven o’clock sharp at Kalaywa Tawya Monastery in Yangon. A seven-year-old sets his alms bowl on the table and sits cross-legged on the dining hall floor. He is one of 1,344 resident monks and represents one of the 19 ethnic groups.2 He cannot recall exactly where he was born, what his name was, and how he ended up here. He only knows that his parents abandoned him for being the “naughtiest” one of his eleven siblings, and that the monks took him in and named him after his spoken language: Karen.3 The longer he stays in the monastery, the more he forgets his family, his language, and his tribe. In a Buddhist society that promotes peace and harmony, how had it come to this for the orphan from the mountains? Buddhism is closely associated with the principle of non-violence, but Buddhist-majority Myanmar has been torn apart by fierce conflicts.4 Despite claims by the current President Thien Sen that the widespread reports of genocide are “a media fabrication,” all minorities – not just Rohingya Muslims – are in dire need of protection. 567 From Rakhine Coast to Kayah Mountains, various peoples suffer from human rights violations in the hands of government forces and armed civilians. James William Hugh BradleyHarrow SchoolEssay CompetitionJunior Category Research Question: If you were the President or Prime Minister of one of the countries in which HART works, what would you do to improve the human rights situation in that country and how would you do it? Not only are they denied citizenship rights, but they are also suffering from violence, discrimination, and land-grabbing.89 Those who stand and speak against such abuses face imminent danger. The international community has focused on the recent skirmishes between Kokang rebels and Myanmar military and the on-going conflict between Rohingya Muslims and Rakhine Buddhists.1011 But let’s not forget the other minority groups – specifically the Karen people – who have been quietly pushed to the margins. Karen are no strangers to marginalisation and consider themselves “orphans” without a homeland.12 Throughout history, they lived at the boundaries and were caught in the crossfire of regional powers; today, seven million Karen continue to struggle against various forms of oppression in Myanmar.13 The government has systematically targeted Karen and employed brutal tactics: compulsory relocation, village annihilation, forced labour, indiscriminate killings, and enforced starvation, just to name a few.14 These human rights violations were highlighted by the Back Pack Health Workers Team in 2006 and further supported by a few advocacy groups.1516 However, with media attention on Muslims and Chinese minorities, the government seems to be getting away with its aggressive campaign against Karen. Besides physical violence, Karen suffer from more silent forms of marginalisation. Since 2011, the government has been assigning less than 3% for healthcare and education.17 It is very unlikely that these funds are allocated to the Karen community. Whereas 50% of Burmese children attain secondary education, the Karen students mostly complete elementary learning level.18 The lack of educational opportunity and the nationalisation of schools are calculated measures by the government to suppress freethinking, cultural consciousness, and economic advancement. 19 Furthermore, the recent splintering of Karen into two main fractions has torn numerous communities apart. The Democratic Buddhist Army is now working with the government to fight against Karen National Union.20 The further marginalized Karen are now fighting against their own people and trying to avoid possible killings, torture, rape, landmines and forced labour. Some have sought refuge in camps administered by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) along the Thai-Myanmar border.212223 The experience of the Karen refugees parallels that of the young Karen monk. He was sick and lost before finding aid within the monastery. The monks not only nursed him back to health but also fed and educated him. And, without their compassion and care, he would not still be here today. In February 1947, General Aung San once said: “If we want the nation to prosper, we must pool our resources, manpower, wealth, skills, and work together. If we are divided, the Karens, the Shans, the Kachins, the Chins, the Burmese, the Mons and the Arakanese, each pulling in a different direction, the Union will be torn, and we will all come to grief. Let us unite and work together…”2425 If we combine the general’s sense of solidarity amongst all ethnic groups with the monks’ practice of compassion for all nationalities, we will be able to improve the human rights situation in Myanmar.26 Of his past life, Karen, the orphan monk, hardly remembers anything at all. Not the bamboo huts, the dusty villages, or the terraced hills. Neither the faces nor the voices. Not the abject poverty or the violent persecution. He doesn’t know what he’s missing, but he still does. He has little knowledge of the conflicts raging outside of the monastery walls, yet he fears the worst. As he joins his fellow novice monks in a chant, he expresses gratitude for the gift of food, prays for his long-lost family, and hopes for peace all across Myanmar. Silence is broken. James William Hugh BradleyHarrow SchoolEssay CompetitionJunior Category Research Question: If you were the President or Prime Minister of one of the countries in which HART works, what would you do to improve the human rights situation in that country and how would you do it? Works Cited: 1 Sohn, Tae Kyung. Karen at Kalaywa Tawya Monastery. 22 July 2012. Photograph. Yangon, Myanmar. 2 http://www.kalaywa.org/index.htm 3 Sohn, Tae Kyung. Personal Interview. 22 July 2012. 4 http://www.globalreligiousfutures.org/countries/burmamyanmar/religious_demography#/?affiliations_religion_id=0&affiliations_year=2010 5 http://www.voanews.com/content/voa-exclusive-interview-myanmar-president-theinsein/2527766.html 6 http://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2014/11/burma-genocide/ 7 http://www.hrw.org/reports/2013/04/22/all-you-can-do-pray 8 http://www.youthforhumanrights.org/what-are-human-rights/universal-declaration-of-humanrights/articles-1-15.html 9 http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-18395788 10 http://www.cnn.com/2015/02/12/asia/myanmar-violence/ 11 http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/10/26/myanmar-clashes_n_2022328.html 12 Gravers, Mikael. “Waiting for a Righteous Ruler: The Karen Royal Imaginary in Thailand and Burma.” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 43.2 (2012): 340-363. 13 http://www.karen.org.au/karen_people.htm 14 http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/on-the-run-with-the-karen-people-forced-to-fleeburmas-genocide-432267.html 15 Milbrant, Jay. “Tracking Genocide: Persecution of the Karen in Burma.” Texas Journal of International Law. 48.1 (2013): 63-100. 16 Falise, Thierry. “On the Run: In Burma’s Jungle Hell.” World Policy Journal, 27.1 (2010): 57-64. 17 http://www.dvb.no/news/war-office-sets-out-ambitious-army-plan/16661 18 http://www.oxfordburmaalliance.org/education-in-burma.html 19 http://www.culturalsurvival.org/ourpublications/csq/article/karen-education-children-front-line 20 Risser, Gary. “Running the Gauntlet: The Impact of Internal Displacement in Southern Shan State.” Humanitarian Affairs Research Project. Asian Research Center for Migration Institute of Asian Studies, 2003: 1-92. 21 http://www.karen.org.au/karen_refugees.htm 22 Tangseefa, Decha. “Taking Flight in Condemned Grounds: Forcibly Displaced Karens and the Thai-Burmese In-Between Spaces.” Alternatives: Global, Local, Political, 31.4 (2006): 405-429. 23 “Road of Resistance.” Online Film. <http://roadofresistance.com/> 24 Deland, Claudio. “Suffering in Silence: The Human Rights Nightmare of the Karen People of Burma.” Karen Human Rights Group. Universal Publishers, 2000. Web. 31 Jan. 2015. 25 http://www.burmalink.org/background/burma/dynamics-of-ethnic-conflict/history-of-armedopposition/ 25 Tanabe, Juichiro. “Buddhism and Non-Violent World: Examining a Buddhist Contribution to Promoting the Principle of Non-Violence and a Culture of Peace.” Journal of Peace Education and Social Justice, 8.2 (2014): 122-149. Web. 31 Jan. 2015. References Considered: Matthews, Bruce. “Buddhism under a Military Regime: The Iron Heel of Burma.” Asian Survey, 33.4 (1993): 408-423. This article discusses the relationship between religion and politics. It describes how Buddhist James William Hugh BradleyHarrow SchoolEssay CompetitionJunior Category Research Question: If you were the President or Prime Minister of one of the countries in which HART works, what would you do to improve the human rights situation in that country and how would you do it? leaders and followers staged the mass protests throughout Myanmar in the late 1980s. It helps me to understand why some Buddhist monks are currently protesting against voting rights for Muslim Rohingyas. It also explains the deep divisions within the Buddhist organisation: old versus young monks; conservatives versus activists; pluralists versus nationalists. It concludes with a very hopeful statement: “Not withstanding these anxieties, Buddhism still remains a potent integrative power, the "soul of the people," and a force that will yet have its say in the destiny of the nation.” I think that Buddhism holds the key to solving the on-going problem in Myanmar. Hayami, Yoko. “Pagodas and Prophets: Contest Sacred Space and Power among Buddhist Karen in Karen State.” The Journal of Asian Studies, 70.4 (2011): 1083-1105. This article focuses on Buddhist Karen and their relationship with other Buddhists. It says that not all Karen are Buddhists and that Buddhist Karen are more likely to support the government. It also says that not everyone practices Buddhism in the same way. It introduces the term “Myanmafication,” which means the government’s policy of enforcing Theravada Buddhism and sidelining local practices. It explains how the central government is tightening its control over the peoples of Myanmar through Buddhism. I wonder if the recent Buddhist monk protests against Muslim Rohingya are secretly encouraged by the government. Dittmer, Lowell. “Burma vs. Myanmar: What’s in a Name?” Asian Survey, 48.6 (2008): 885-888 This article explains the reason for changing the country’s name from Burma to Myanmar. It helps me to understand the history of Burma and the current situation in Myanmar. It describes the conflict between national majority and ethnic minorities. It also explains the difference between “splittist tendencies” and “counterinsurgency operations.” It included information about how Karen signed a truce with the government in 1988 and why Karen started rebelling again in 2006. It confirms that human rights abuses have never really stopped. I recognise that something radical must be done to improve the situation for minorities in Myanmar. Silverstein, Josef. “Civil War and Rebellion in Burma.” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 21.1 (1990): 114-134. This article describes Burma’s history of civil war and minority rebels. It says that General Aung San passed a constitution to unify Burma but that it forced a “union of unequal states.” It goes on to explain how the civil war was divided into different stages and why Karen were seeking autonomy and self-determination. It helps me to get familiar with specific terms, such as People’s Volunteer Organisation (PVO) and Karen National Union (KNU). I realise that the government’s nonstop campaigns against Karen won’t ever be successful. Kinley, David. “Engaging a Pariah: Human Rights Training in Burma/Myanmar.” Human Rights Quarterly, 29.1 (2007): 368-402. This article states that Myanmar’s human rights record is “one of the worst worldwide.” It describes how the military dictatorship has been destructive economically, politically, socially, and legally. It also discusses how the West and the East has responded to this humanitarian crisis. The Western nations have tried to pressure the government with “diplomatic condemnation, imposition of economic sanctions and withdrawal of international aid.” The Eastern nations have followed the policy of “non-interference.” The author suggests that Australia’s “Third Way” – hosting human rights training program for government officials – James William Hugh BradleyHarrow SchoolEssay CompetitionJunior Category Research Question: If you were the President or Prime Minister of one of the countries in which HART works, what would you do to improve the human rights situation in that country and how would you do it? may be the best way to help Myanmar sort out this human rights situation. I am not so sure if this training program will end the conflict between the powerful majority and the ethnic minorities. Bray, John. “Ethnic Minorities and the Future of Burma.” The World Today, 48.8 (1992): 144-147. This article describes Burma’s ethnic diversity. It pinpoints the Karen Revolution of 1948 as the beginning of Burmese army offensives. It also says that the government ended its operations in 1992 as “a gesture of solidarity.” It’s interesting to know that the Karen form the largest minority group and that majority are Buddhists. The author warns that Karen are often mistaken as Burmans just because of their religion. He confirms that they “maintain a strong sense of their own identity” and that Karen rebel leaders saw “the creation of an independent state” as the only “guarantee for their people’s safety.” He also explains how the long civil war has “embittered those at the receiving end of army operations and made it difficult to accept the authority of central government.” He says that it’s “not feasible for all minority groups to form their own independent states” and that they should “aim for ‘genuine’ federal union.” He knows that “deep seated mistrust” is the biggest obstacle for Burma but argues that “federalism” is better than “secession.” He then makes these suggestions: “preservation of national unity as a major objective,” “constitutional changes for minority groups,” “commitment on all sides to remove the prejudices.” I agree with him, but I believe that these goals are easier said than done. Clarke, Gerard. “From Ethnocide to Ethnodevelopment? Ethnic Minorities and Indigenous Peoples in Southeast Asia.” Third World Quarterly, 22.3 (2001): 413-436. This article is mostly about government policy towards ethnic minorities. But I find his descriptions of Burmese government to be the most interesting: “unofficial policy of 'Burmanisation' was launched and sustained well into the 1990s”; “policy of forced relocation known as 'four cuts'” was applied in rural areas; “urban development programmes” was to break up ethnic minority communities and relocate them to “new resettlement towns.” He also discusses the results: “intense military conflict,” “insurgent armies organised along ethnic lines,” “tens of thousands of civilian deaths,” “hundreds of thousands of refugees, ” “significant adverse effect on development in ethnic minority areas,” “ethnic minorities underrepresented in the government, the bureaucracy and the military,” “ethnic minority states and regions being the poorest in the country,” and “demoralisation of Karen communities.” Without this article, I wouldn’t have been able to come up with my own ideas on how to improve the human rights situation in Myanmar. Posner, Eric. “Human Welfare, Not Human Rights.” Columbia Law Review, 108.7 (2008): 17581801. This article is generally about the importance of human rights treaties in international relations. It argues that these treaties aren’t very effective at all and that “international concern should be focused on human welfare rather than on human rights.” It also suggests that “foreign aid could be better coordinated so as to help those who need it most.” I agree with his arguments, and I think that social welfare reform is necessary to lessen the sufferings of ethnic minorities in Myanmar. South, Ashley. “Karen Nationalists Communities: The “Problem” of Diversity.” Contemporary Southeast Asia, 29.1 (2007): 55-57. This article traces the root of Karen ethno-nationalism back to the colonial period. It was really interesting to read about how British officials and Christian elites tried to “impose a homogenous James William Hugh BradleyHarrow SchoolEssay CompetitionJunior Category Research Question: If you were the President or Prime Minister of one of the countries in which HART works, what would you do to improve the human rights situation in that country and how would you do it? idea of “Karenness” on this diverse society.” The author says that the concept of autonomy is actually being legitimized by “outsiders, including missionaries and (more recently) human rights activists and aid workers.” He also says that, ironically, Karen unity has broken up the Karen community. He argues that Karen must find “unity in diversity” by rebuilding “civil society networks within and between Karen communities,” and “accepting the segmented nature of this "plural" society.” He also warns that ruling by “grand coalition” would be impossible without “the provision of minority vetoes, proportional representation in decision-making, and federalism.” I like this idea of “unity in diversity” because it may succeed in healing old wounds and helping Karen move forward. Theodorson, George. “Minority Peoples in the Union of Burma.” Journal of Southeast Asian History, 5.1 (1964): 1-16. This article covers the history of ethnic minorities after the independence of Burma. It discussed why some Karen “accepted the impracticability of a separate nation” and “favoured the establishment of a Karen State” inside Burma. It also said that establishing a “satisfactory state” was impossible because Karen were “scattered among the Burman population in the delta” and through the Burmese hinterlands. I realise that social and political integration is the only way to resolve the conflict between the government and the Karen people. Silverstein, Josef. “Nationalism as Political Paranoia in Burma: An Essay on the Historical Practice of Power by Mikael Gravers.” Journal of Southeast Asia Studies, 31.1 (2000): 215-217. This article reviews an essay by another writer. I couldn’t find Graver’s essay in the library or online, so I had to rely on this article for some key information. It relays information about the role of Buddhism in recent developments, the split between Christian-led Karen National Union and the Democratic Karen Buddhist Organization, and the failure of a Western-style national election. However, it criticizes Graver for assuming that “Buddhist-based model is not antiethnic,” overlooking the fact that “ethnic minorities are not fully equal with Burman-Buddhists,” ignoring “Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, the National Democratic Front and the other members of the society who believe in the ideas of a plural society, political equality and democratic rule,” and dismissing the suffering of “Karen in their half-century of civil war.” It argues that Karen Buddhist Organization is backed by the junta and that its goal is to undermine the KNU and become “the voice and leadership of the Karen community.” It concludes with some really thought-provoking questions: “Is this the solution to the Kachin and Chin problems as well? Are all destined to accept religious conformity or die? Is there any acceptable alternatives to the racist state the Burma army leaders are busy trying to impose on the nation?” I am thankful for these questions because they are making me second-guess my idea about Buddhism. Thomson, Curtis. “Political Stability and Minority Groups in Burma.” Geographical Review, 85.3 (1995): 269-285. This article explains why political stability is so “elusive” in Burma. It argues that minority groups “lack long-term attachment or loyalty to a political entity larger than the clan, tribe, or chiefdom.” It gives an example of Karen and they do not “adhere to a single identity or paramount loyalty.” It argues that “the unitarist policy of the central government is not conducive to integration, because it focuses on assimilation to an identity that has never been an important component in the territories controlled by the minority groups.” From this article, I favour pluralism over assimilation. James William Hugh BradleyHarrow SchoolEssay CompetitionJunior Category Research Question: If you were the President or Prime Minister of one of the countries in which HART works, what would you do to improve the human rights situation in that country and how would you do it? Boonlue, Winai. “Karen Imaginary of Suffering In Relation to Burmese and Thai History: Conflict, State, Non-State Segmenting and Splitting on Religion, Community, etc.” Center for Cultural Resource Studies. Kanazawa University, n.d. Web. 31 Jan. 2015. This article describes Karen background and analyses its impact on Karen today. It identifies Karen as “borderlanders” because they have always been living in “borderland regions of different cultures throughout many countries” and “placed in the margins where the human conditions were so difficult to endure.” Next, it explains Karen myths, “The Tale of the Orphan and the King” and “The Tale of Orphan Tiloola,” to show how “a nobody was able to live in this world successfully.” I find these stories so interesting because it reminds me of the real-life Karen the orphan. My aunt visited Kalaywa Tawya Monastery two and a half years ago, and she spent some time talking and photographing Karen. When she shared his story with me, I was really touched but didn’t think that I would ever do anything with it. But as soon as I read this article, I knew that I had to focus on Karen’s suffering – as a boy and a people – and that I should look into how the two Karens have been marginalised and what can be done to improve their situation. The author says: “The most powerful argument of borderlander has been “We have never been transgressing state boundaries, but the state has always been transgressing our lives.” Borderlanders do not cross the line but the “line” has cross their lives. Then we need to cross the lines.” Last but not least, he shares his personal experiences with Karen refugees. I found his story of Nau Hku and his photograph of Nau Hku’s family to be very moving, so I asked my aunt if she would like to share Karen the orphan’s photograph with me. She said, “Yes.” Now I am trying to crossover and passing it on to you. James William Hugh BradleyHarrow SchoolEssay CompetitionJunior Category