entangling-v3c - Center for Computation & Technology

advertisement

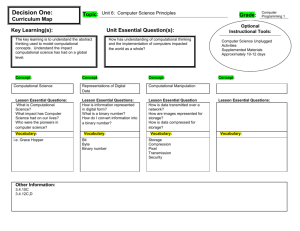

Entangling space, form, light, time, computational STEAM, and cultural artifacts Brygg Ullmer, Louisiana State University Department of Computer Science + Center for Computation and Technology (CCT) Two decades ago, three paradigms were birthed that have grown mightily. The Web, for which Berners-Lee released the first browser and server in 1991, needs no introduction. Weiser’s 1991 “ubiquitous computing” (or ubicomp) vision has similarly blossomed, with many of his postulations now regarded as lived reality [13]. While a quieter birth (first as a two-week student project), Bishop’s 1992 “marble answering machine” is also familiar to many interactions readers [3]. With its physical marbles acting as embodiments of voice messages, and their manipulation offering fluid engagement with digital “contents” and metadata, Bishop’s conception has greatly influenced both tangibles researchers (e.g., as discussed in [7]) and the interaction community more broadly. The Web, ubicomp, and tangibles were first articulated as entirely independent phenomena, with few hints of mutual awareness. While separated at birth, we feel their present and future are entwined with increasing intimacy. To borrow a quantum metaphor, we see the Web, ubicomp, and tangibles as entangled – both with each other, and with crosscutting notions of space, form, light, and time. More than a philosophical diversion, this entanglement is actionable, with real implications for substantial impact. We illustrate this with and consider future prospects for computational STEAM (science, technology, engineering, the arts, and mathematics) and cultural artifacts, which we argue may also be seen as productively entangled. Space Consider space. People presently use cyberspace, the Web, the Net, and the cloud somewhat interchangeably as descriptors for online realms of diverse virtual artifacts. In parallel, physical space – architectural space, urban space, and beyond – is a central, if too often neglected, canvas and foundation for both ubicomp and tangibles. Indeed, Bishop long expressed frustration that in excitement over his marbles and machine, many forget that his conception centered upon a spatially-situated ecology of interacting products. We find deep intersection and resonance between virtual and physical spaces. Introducing “tangible bits,” Ishii and I spoke of “dual citizenship” – for both humans and tangibles – between physical space and cyberspace [7]. Citizenship should not be taken lightly. The tangibles of Bishop, ourselves, and others are first-class members of both physical and cyberspace, of corridors and clouds, with all the rights, privileges, and responsibilities accorded to each. Conversely, it is fruitful to consider pervasive physical-world entanglements of cloud content – especially as relates to form (beyond tags), light, and time. Form Like space, form evokes many productive entanglements between cyberspace and the physical world. Webster introduces “form” in terms of shape, structure, and nature. Again, consider the Web. The Web manifests itself in many different forms. Some pages are plaintext; others richly, dynamically structured, heavily interwoven with hyperlinked content. These reflect the diverse (and in the long view, still embryonic) nature of Web content – from simple documents, to perpetually evolving Facebook pages and online forums, and far beyond. In a different sense, one can view the <form> tag and its manifestations as one early foundation upon which the Internet’s commercialization is grounded. Further afield, in Gibson’s “Mona Lisa Overdrive,” the character Gentry “was convinced that cyberspace had a Shape, an overall total form; [and] this obsessive conviction that the Shape mattered totally.” Recent echoes can be seen in the March 2012 “Operation Global Blackout” threats against the Internet’s domain name system (DNS). In the original ubicomp vision, the diverse, complementary physical forms of Weiser’s grounding artifacts – tabs, pads, and boards – together with their spatial situatedness, are foundational to the underlying argument. As for tangibles, formgiving and shape languages are for many practitioners (especially product designers) among the most central intellectual activities and concerns. Why is this discussion of form relevant? While the tangibles community’s associations of physical objects and Web content date at least to the hypercards of [7], common practice stands at a “pre-HTML” stage – one object, one link; and then rarely (if ever) supporting entanglements between diverse systems of disassociated creators. Uses of QR codes and augmented reality tags from magazines and posters offer a clear, if highly limited, example of entangling physical and virtual forms. But again, such present uses stand at less than a “Web 1.0” stage of maturity (at least in the West); one of minimal human legibility and limited malleability for many visual+physical design goals. In short, our current virtual and physical forms are at best loosely entangled, bringing varied costs and lost opportunities. In a time when attention is among the scarcest of human resources, modal isolationism between online, screen, and tangible realms can be seen as fostering psychosislike (“loss-of-contact”) states. For example, the decades-long waxing and waning of online virtual worlds might be seen as partial consequence of insufficient entanglement with our physical world, to allow increased human awareness and presence both in our on-and off-screen orbital phases. Prospective faults are easy to find; harder, how might entanglement help? Light From the vantage of human habitats, light itself can be seen as undergoing not only technical, but also conceptual transformations. The progression toward pervasive use of solid state (e.g., LED) light sources deepens prospects for computational entanglements [2]. To be sure, an LED light bulb th can be controlled by a 19 century switch as easily as like-vintage incandescent bulbs. Simultaneously, with our habitats now bathed in WiFi and other Net-linked carriers, it is progressively easier to envision a time when the majority of artificial illumination is cloudentangled. With Web-entangled light, shadows of cloudspace – mediations of people and processes near and far, and countless variations – take on new liberties for play beyond the bounds of our rapidly multiplying screens [12]. Where graphic design has long concerned positive and negative space, the kinds and ratios of emissive and non-emissive surfaces, and fine-and course-grained light (both spatially and temporally) could give rise to analogous themes, with substantial implications for attention and interaction. Marshall McLuhan presaged these themes with his assertion “the medium is the message” and discussions of “hot” and “cool” media (considering varying implications for audience engagement across different mediums). High-intensity emissive and projective displays can tend to seize visual attention. Alternatives such as diffusely illuminated passive artifacts or bistable (e.g., e-ink) displays, entangled with cloud-sourced stimuli, prospectively offer legible, actionable, aspirational, and inspirational ambient immersion in mixed physical/digital space [2, 7]. Several of our recent efforts in this arena are visible in Figure 1. Time For decades, HCI (human-computer interaction) has fixated its concerns at and around the 100ms threshold of interactivity. Inspired by Dyson’s powers-of-ten consideration of past and future time [5], we briefly consider powers of ∼ten thousand: milliseconds, minutes, months, and millennia. Milliseconds and minutes are well-understood to HCI, as today’s native habitat for all things digital. As a tool for thought regarding longer timescales, the shrines and temples of Japan offer both a compelling example and our inspiration for Figure 1. Figure 2 shows signage entangled with ancient Japanese practices accompanying the maintenance of temples and shrines. These buildings in many cases date back a thousand years or more, with wood a dominant structural material (and earthquakes a too-frequent companion). Given this, maintenance – and the funding necessary to support this – has both pragmatic and spiritual significance. nd As one extreme, the temple of Ise has been rebuilt every 20 years since ∼A.D. 680, with the 62 reconstruction scheduled for 2013. (The exact rationale for this long tradition is unclear; among various asserted spiritual connotations, one suggestion involves training each new generation of architects in the traditional techniques of their ancestors.) In such contexts, Figure 2 depicts a wall recounting benefactors across long time (here, for Nan’endō at Kōfuku-ji in Nara). Of course, not all Japanese architecture elements are bound to the eternal. For example, rice paper windows and walls were often replaced every one to two years. These examples encourage us to contemplate prospects for interface artifacts with aspirations toward heirloom and UNESCO World Heritage status. Of equal interest are compostables, with aspirations toward net-positive total cost of ownership / whole life costs [4]. An example of compostable tangibles is illustrated in Figure 3. Computational STEAM Thus far, we have considered philosophical entanglements between space, form, light, and time. Having done so, it is worthwhile to consider examples illustrating how these ideas can be operationalized. We consider two diverse examples – computational STEAM and cultural artifacts – partly with an eye toward generalization, and partly to explore their own mutual entanglement. Computational STEAM is an extension of computational science. Computational science has been heralded as a third pillar of scientific inquiry, joining theory and physical experimentation [14]. It concerns scientific inquiries that can only be conducted through use of high-performance computing. For example, in our work with computational genomics, we routinely task hundreds of compute cores for days or weeks on end to analyze hundreds of millions of DNA fragments, as part of efforts uniting dozens of collaborating science teams spanning the globe (e.g., [8]). Computational science is also deeply interwoven with the Web’s origin. Berners-Lee conceived the Web initially as an enabler for CERN particle physics efforts, where single papers sometimes include more than a thousand co-authors. Similarly, Andreessen and team developed the Mosaic web browser (evolving into Netscape and Firefox) at NCSA, a supercomputing center. STEAM is a variation of the familiar acronym STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics), with the added “A” signifying the Arts (including design, fine and performing arts, craft, and architecture). STEAM has been the subject of growing activity – for instance, the recent NSF-funded workshop “Bridging STEM to STEAM” at the Rhode Island School of Design. One view of STEAM-entangled arts can be seen as analogous to the doping of semiconductors (a process fundamental to microprocessors and most solid-state electronics). There, on the order of one dopant atom per 100 million base atoms (for light doping; in other cases, a heavier mix) can radically transform material properties. Similarly for STEAM, the arts can play transformative roles in representing and communicating complex STEM activities, provoking contemplation of their implications, anchoring these in diverse cultural contexts, and inspiring broader impacts. Our team has developed tangible interfaces servicing computational STEAM for roughly a decade. Figure 4 provides one example – here, a Microsoft Surface, Apple iPad, and custom electronics devices being used to collaboratively engage with a visualization of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. As with most digital interfaces, the depicted interaction is primarily conducted at the milliseconds and minutes timescales. While sharing these short-timescale dynamics, the larger temporal and human scales of our computational genomics efforts – with hundreds of collaborators, each perhaps averaging a ∼1000 hour investment over years on a single project – stretch the capacities of traditional HCI, and have compelled us to embrace entanglement. The illustrations of Fig. 1 depict an architectural-scale project exploring entanglement, here with corridor content engaging both computational STEAM and cultural events. Cartouches and casiers – part web-born cloudstuff, part physical avatar, loosely serving as the words and sentences of simple tangible grammars [11] – represent elements such as people, SVN data repositories, papers, funded research projects (legacies of Kōfuku-ji and Ise), supercomputers, and more. As pictured, we restructure light so that all illumination is sourced below the knees (allowing the floor to be safely traversed), through screens and Surfaces, or through back-and sideilluminated cartouches by way of hundreds of Web-entangled RGB LEDs. This ecology of interactors allows the state of diverse entanglements to be monitored – the physical and virtual state of people, data, etc. – and acted upon. Arrays of embedded Microsoft Kinect sensors will allow the act of pointing to these cartouches to retrieve their associations to the integrated screens, and simultaneously change the ensemble LED states to show related entanglements. Small illuminated, capacitively-sensed cartouches ringing the screens’ bezels provide complementary direct-touch access to the same or complementary information. Detailed elaboration upon this entangled wall is a topic for other venues. Here, we feel it primarily important to note the temporal dimensions of this wall content. Many organizations’ data repositories for papers, grants, talks, and their ilk span decades (if not longer). Similarly, tenured faculty often reside for decades; but these durations are also daily marked by 18 hour showers of activity entangled with numerous students and colleagues near and far. Closely synergistic with the Japanese temples, we intend for the cartouches representing funded projects – and through them, images, videos, papers, talks, datasets, participants, and other entanglements – to live over long durations (months to millennia) on these walls, speaking through (e.g.) Google Scholar citation tracking of research funding’s impacts long after the students have gone. Even the supercomputers represented by the wall’s cartouches have surprising entanglements with Ise and its kin. A supercomputer – whether costing US$200K or $200M – has an expected lifetime of roughly five years. Within this narrow window, such machines are enswirled by a mad race to make the most of their brief lives. Yet many supercomputing results transcend time. For instance, the first supercomputer entangled within Figure 1, Supermike, was used to calculate Hurricane Katrina storm surge simulations, calculations partially motivating the first mandatory evacuation of New Orleans. While the storm claimed thousands of lives, in the absence of Supermike the numbers might have been far worse. While Supermike has long since been decommissioned, this is a computational result worth remembering a thousand years (and more) from now. Our entangled wall provides a step toward a plausible path for celebrating this impactful heritage. Cultural artifacts For the remainder of this article, we consider another past-and future-oriented trajectory: the entanglement of cultural artifacts. To begin, consider the term “plurality.” One interpretation is a core thesis of ubiquitous computing: trends toward more numerous and functionally diverse computational devices. st Plurality is also used as a synonym for “pluralism” and “cultural pluralism,” defined in the 21 Century Lexicon as “a condition in which many cultures coexist within a society and maintain their cultural differences.” In his memoirs, physicist Freeman Dyson writes “in biology, a clone is the opposite of a clade.... This... has its analog in the domain of linguistics. A linguistic clone is a monoglot culture.... Linguistic rejuvenation requires the analog of sexual reproduction, the mixture of languages and cross-fertilization of vocabularies.... In human culture as in biology, a clone is a dead end, a clade is a promise of immortality. Are we to be a clade or a clone? This is perhaps the central problem in humanity’s future.” Dyson’s proposition has deep implications for HCI – and far beyond. On the one hand, the systems we have illustrated in Figures 1 and 4 heavily leverage mainstream smart phones and tablet computers. From the perspective of early 2012, paralleling the last few decades of desktop computing, the convergence of mobile devices toward a small handful of operating systems again raises the prospect of HCI “clone culture.” As noted by the late Kees Overbeeke [9], this trajectory remains populated by computational devices intentionally designed with universal “Ulm school” product language, abstractly sculpted to find equal comfort across diverse cultures. As an illustrative counterexample, Overbeeke suggested the Dutch bonensnijmolen – a particular kind of bean cutter pervasive in Dutch culture, and unknown to others – as one of myriad examples of culturally-specific design, with strong implications for computational artifacts. Sister examples include Japanese genkan, Chinese red envelopes, and Swiss Appenzeller festival hats. We close by introducing two such culturally specific artifacts, birthed centuries and worlds apart, but each offering incisive lenses and prisms toward entangled futures. The first is a page of “Canon Tables” within an illuminated manuscript now more than 800 years old (depicted and described in Fig. 5). Its painted “illuminations” of gold and silver cry out for awakening as perhaps still-functional capacitive touch sensors; the precious gems encrusting its covers, as lenses for entangled digital light1. Today, much conventional wisdom casts physical books as all but obsolete. This ancient monastic handwork suggests a profoundly different alternative. The entangled “function” of the above excerpted page – as comparative cross-index to the Christian Gospels, reinterpreted as illuminated hyperlinks to otherwise scroll-like digital texts – is at least as relevant today and appropriate to its physical medium as when first inscribed. Far from limited to religious studies, such an approach could be equal cogent for secular messages as diverse as competing budgets from divergent political factions, to scientific domains such as comparative genomics. A world away in medium and message, but latently a sister in entangled prospects, the memory boards of the Luba Lukasa use bits of shell, wood, and stone inset over generations to record important functional and spiritual features of an embodied memory landscape (Figure 6; [10]). Originally passive placeholders for an oral culture, each pinned piece can be seen as a prospective cloud-entangled interactor – for recording or accessing stories or music (whether ancient or live), communicating with remote relatives, monitoring natural phenomena, and countless other prospective entanglements. Be they of Lukasan, Lakotan, or Laotian hands – by monks, artisans, chancellors, or children – tangibles and broader entanglements can be viewed as mediums through which cloudstuff can be interwoven with diverse spaces, forms, lights, and times, yielding artifacts ranging from enduring heirlooms to compostable transient stuff. While we have prototyped contemporary entangled cultural artifacts, including Web-entangled Nepali prayer boxes and mnemosynetic music boxes, we have been counseled toward caution in sharing them prematurely. The rationale concerns the criticality of cultural provenance – of such artifacts arising from the hands, minds, and souls of native voices, rather than imposed by interested outsiders. We hope our examples offer prospective exemplars and enthusiasm toward near at hand, high-impact prospects. We believe the most promising of these will likely not be purely imitative of past artifacts, but rather hybrid entities – as for all children, bearing some ancestral traits, with others novel and distinctive. We hope the lens of entanglement may provide a fruitful view to the rich interplay and 1 Related prospects have been compellingly illustrated in the books, walls, and clothing of Buechley and collaborators [5] complementarity of the Web, ubicomp, and tangibles. We have also endeavored to illustrate old and new dimensions to synergisms and fusions between the STEM disciplines with arts and culture. Ours is a fertile and demanding time for new mediums and messages – and one crying out for paths that engage our world’s many peoples in their responsible production, consumption, and use. Acknowledgements The research described and pictured was the product of many hands and minds. Figure 1 efforts were co-lead by Narendra Setty, Landon Rogge, Chris Branton, Jeremy Grassman, Rod Parker, and Robert Kooima. Wall2 and Wall3 efforts were co-lead by Debra Waters, Colby Jordan, Courtney Barr, Phil Winfield, Kevin Nguyen, Stephen Tanguis, and Jesse Allison. Figure 4 efforts were co-lead by Claudia Gil, Christian Dell, Alex Reeser, and Cornelius Toole. Co-implementation of these projects was by Benjamin Birk, James Hamilton, Isaiah Joseph, Phillip LeBlanc, Rajesh Sankaran, Suroj Shrestha, Christian Washington, Andr´e Wiggins, Tim Wright, and many others at LSU. Thanks to John Underkoffler of Oblong, and Bernt Meerbeeck, Dzmitry Aliakseyeu, and others of Philips Research, for inspiring discussions concerning the future of light(ing). Special thanks to Miriam Konkel, William Bainbridge, Joanna Berzowska, Karin Conynx, Nadine Couture, Hali Dardar, Kristina Höök, Elise van den Hoven, Hiroshi Ishii, Robert Kahn, Kees Overbeeke, Rita RodriguezAnger, Sho Shibata, Joel Tohline, Jean Vanderdonckt, and Ron Wakkary for many invaluable motivating conversations. This research was funded by NSF (CNS-0521559, CNS-1126739, IIS0856065, and EPSCoR), NIST CDI, LSU CCT, and the Louisiana Board of Regents. Figures Figure 1. Hallway space with computationally + physically entangled content. Above: back- and side-illuminated cartouches display activity in document space (SVN-based code, papers, designs, etc.) and people space (both via social media and physical presence). Below: virtual and physical posters allow both content viewing, and awareness of entangled activity, both locally (associated files and people) and remotely (e.g., associated citation activity). Interactivity with entangled content underway both through wall display, Microsoft Surface 2 (SUR40, under retrofitting for convertible vertical+horizontal use), smart phones, and arrays of Microsoft Kinects (detecting both pointing and presence). All interoperate with tech in other spaces. Figure 2: Sign recounting patronage of Nan’endō Kōfuku-ji in Nara, Japan. Figure 3: Tablet computer tangible enclosures of wood and paper (casiers [10]) undergoing mechanical and biological decomposition (in a NatureMillTM heated robotic composter). Figure 4: Microsoft Surface and cartouches + casiers [10], used to engage with a visualization of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Here, one casier is back-illuminated and -sensed by an Apple iPad tablet; the tablet; the other, physically identical, is bidirectionally mediated by the Surface itself. Figure 5: Illuminated manuscript with Canon Tables: “lists of primitive chapter numbers arranged in columns so that a reader of the four Gospels could match up parallel passages in different texts.” (ca. 1170, St. Albans Abbey; Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS. 48, fol. 201v.) From “A History of Illuminated Manuscripts,” de Hamel, 1994. Figure 6: “Memory board” of Luba Lukasa (migratory African tribe) [9]. References [1] ADAMS, C. Japan’s Ise shrine and its thirteen hundred-year-old reconstruction tradition. In Journal of Architectural Education 52, 1 (September 1998), 49–60. [2] ALIAKSEYEU, D., MASON, J., MEERBEEK, B., VAN ESSEN, H., AND OFFERMANS, S. The role of ambient intelligence in future lighting systems. In Ambient Intelligence, vol. 7040 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer, 2011, pp. 362–363. [3] BISHOP, D. Marble answering machine. http://tangint.org/v/1992/bishop-rca-mam/, 1992. [4] BLEVIS, E. Sustainable interaction design: invention & disposal, renewal & reuse. In Proc. of CHI’07 (2007), pp. 503–512. [5] BUECHLEY, L. Questioning invisibility. Computer 43, 4 (April 2010), 84 –86. [6] DYSON, F. Evolution. In Imagined Worlds. Harvard University Press, 1998. [7] ISHII, H., AND ULLMER, B. Tangible Bits: towards seamless interfaces between people, bits and atoms. In Proc. of CHI’97 (1997), pp. 234–241. [8] LOCKE, D. P., HILLIER, L. W., WARREN, W. C., WORLEY, K. C., ET AL. Comparative and demographic analysis of orang-utan genomes. Nature 469, 7331 (January 2011), 529–533. [9] OVERBEEKE, K., DJAJADININGRAT, T., HUMMELS, C., AND WENSVEEN, S. Beauty in usability: forget about ease of use! Taylor & Francis, 2002. [10] ROBERTS, M. N., AND ROBERTS, A. F. Memory: Luba art and the making of history. African Arts 29, 1 (1996), pp. 22–35+101–103. [11] ULLMER, B., DELL, C., GIL, C., TOOLE, C., AND ET AL. Casier: structures for composing tangibles and complementary interactors for use across diverse systems. In Proc. of TEI’11 (2011), pp. 229–236. [12] UNDERKOFFLER, J., ULLMER, B., AND ISHII, H. Emancipated pixels: real-world graphics in the luminous room. In Proc. of SIGGRAPH’99 (1999), pp. 385–392. st [13] WEISER, M. The computer for the 21 century. Scientific American 272, 3 (1991). [14] WILSON, K. Grand challenges to computational science. In AIP Conference Proc. (1988), vol. 169, p. 158.