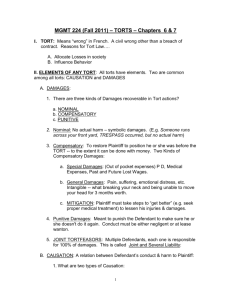

Spring Outline Torts

advertisement