Sermon - Church of the Advent

advertisement

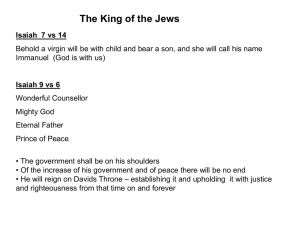

The Rev. Marc Eames Christmas II January 3, 2015 This is my first of a brief two part 8:00 sermon series on the immediate aftermath after Christ’s birth. In a quirk of the Lectionary, the story is told out of order. So I will begin with sermon 2 and work backward. The Christmas story is filled with good news. The Son of God, the Word made flesh, dwelt among us in the person of Jesus Christ. Good news was delivered by angels to lowly shepherds. But after the shepherds leave, we are left with a truly terrible story that the church long ago named “the slaughter of the innocents.” This story is buried in the lectionary and is infrequently read. It is usually our practice to do the Epiphany Pageant this Sunday, so we would have used the readings for the Feast of the Epiphany which we will do next week, but, today, we are left with this dark story which leads to Jesus, Mary, and Joseph becoming refugees in Egypt. Herod the Great was a truly bloodthirsty and paranoid man. He was smart, crafty, political, and ambitious. The closest comparison I can make to anyone in history is Joseph Stalin. Both had the same violent drive for greatness achieving their goals with ever increasing numbers of bodies being buried. Where they are different is that Stalin had a powerful opponent, Herod was able to convince the Romans that he was the best person to pacify the pesky Jewish population. With the Romans backing, he was able to channel his positive energy into amazing building projects. The second temple where Jesus and Peter preached was a marvel and a far cry from the one that Nehemiah helped build five centuries earlier. Nehemiah’s foundation had as much to do with Herod’s temple as the small Puritan houses here in Medfield have to do with the modern much added on to buildings that currently exist. “Historic building”? Well, sort off. Herod also built the famous and still used theatre, city, and artificial harbor at Caesarea. Modern archeologists still don’t know how he did it. He was driven. He expected the impossible and perhaps achieved it. He used his murderous reputation to good effect in his building projects. If he didn’t think his reputation was scary enough, he threatened them with the might of the Roman Empire. Like Lord Vader in Return of the Jedi, he would visit construction sites he was concerned with, and he would threaten them. If he was told that they were on schedule, he could say, “The Emperor does not share your optimistic appraisal of the situation.” Perhaps ending with “The emperor is not as forgiving as I am.” Herod would stop at nothing to get what he wanted, and he murdered every conceivable threat. He was certainly not against the killing of children. He killed several of his own children including Herod Alexander who by all accounts, even of his enemies, was an honorable and gifted man. I have no doubt that Herod ordered the murder of those children in Bethlehem. Not because he had to, but because he could. He took every threat, no matter how weak or tiny, as a serious danger. Several times in Joseph Stalin’s life, he really thought he was going to be murdered and overthrown. Especially when the Nazi’s first invaded. I think Herod really thought that his first wife was plotting against him. I think he really thought his son Alexander was going to have him murdered. I think he really thought a baby was a threat to him. This story of the slaughter of children is one of the most power in scripture because, unfortunately, it has happened so many times. So many times in history, the possible death of family members has been used to threaten people. So many times in history, has a mother desperately tried to hide her child from villains. One of the most beautiful artistic responses to this tragic story is the Coventry Carol. The Carol was originally written in the 14th century for the play the Pageant of the Shearmen and Tailors, and it was later modified in the early 16th century. In the Middle Ages, plays about the bible were very common. Every year the city of Coventry performed plays about Christmas and the aftermath. This song came from that tradition. The carol captures the sadness of that time, “1. Lullay, Thou little tiny Child, By, by, lully, lullay. Lullay, Thou little tiny Child. By, by, lully, lullay. 2. O sisters, too, how may we do, For to preserve this day; This poor Youngling for whom we sing, By, by, lully, lullay. 3. Herod the King, in his raging, Charged he hath this day; His men of might, in his own sight, All children young, to slay. 4. Then woe is me, poor Child, for Thee, And ever mourn and say; For Thy parting, nor say nor sing, By, by, lully, lullay.” The lyrics are rather dark. They seem to end on a helpless note that the children will all be killed. The lyrics do not reveal what the music foreshadows. The music ends on a Picardy third. This means that the music ends in an unexpected shift to the major key with a note in the upward direction. It is always seen as positive in music theory. The music suggests that Jesus will escape into Egypt surviving yet another perilous situation. The lyrics stand as they are, though. Many children died. Their suffering is not to be tossed aside, but hope honors their loss. This carol was very nearly lost. Hundreds of carols from the middle ages were burned by the Puritans. Many more have been lost to the ravages of accident and time. This carol was saved by an antiquarian, but it was not widely known until World War II. In the Second World War, the great Medieval Cathedral of Coventry was bombed and destroyed by the Nazis. On Christmas of 1940, in that crippled and gnarled house of worship, a group of woman sang the Coventry carol. They sang of hope through the very real loss of the sons and daughters of Coventry at the orders of an evil man. That song which was broadcast on BBC moved a nation, and we continue to sing it to this day. It is a beautiful response in the face of wanton human cruelty. Mary, Joseph, and the young Jesus escaped into Egypt. We are not told where they stayed, but they are thought to have been there for about 2 years. When King Herod died, his kingdom was split among his three sons all of whom were an improvement on Herod’s evil, but all of whom were incompetent. The Tetrarch Herod Archelaus’ rise to the thrown in Judea was a welcome sign to the refugee family, but he was also a possible danger. According to the great Jewish historian Josephus, Archelaus and his foes had some serious fights in Jerusalem causing Archelaus to cancel Passover. Matthew reports that an angel let Joseph know about the danger, and the family returned to Nazareth in Galilee. Joseph, Mary, and Jesus seemed to have never returned to Bethlehem. In Nazareth, Jesus grew up in relative peace, but he always knew what had happened in his early life. This no doubt helped Jesus identify with the poor and with those in danger whether from disease, political violence, or even from terrible loneliness and separation from all one knows. In his name. Amen.