Full Text (Final Version , 2mb)

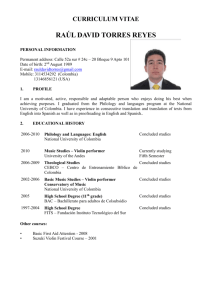

advertisement