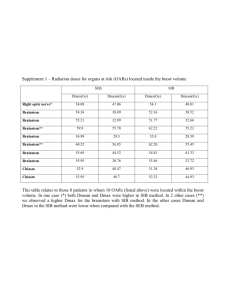

Electronic supplementary material Warm ischemia times and

advertisement

Electronic supplementary material Warm ischemia times and functional outcomes for donation after cardiac death Organ Warm ischemia Comments time (min) Kidney 120 min Up to an additional 120 min warm ischemia time in selected donors Higher incidence of delayed graft function compared to DBD donors, but similar long-term function pre-clinical evidence of augmented immune response in transplanted kidneys with prolonged warm ischemia time and older aged donor Terminal donor acute kidney injury (not requiring dialysis) may not impair recipient or transplant outcomes Extended donor kidney pool now being considered, but associated with poorer 2-year graft function Lung 60 Impact of specific donor interventions not evaluated Warm ischemia time related to time to re-inflation of lungs rather than cold perfusion Similar outcomes to recipients of organs from DBD Pre-explantation bronchoscopy to document bronchial anatomy, evaluate degree of lung injury (including infection) and to rule out suspicious lesions If donor extubated when treatment is withdrawn, donor reintubation (without ventilation) is required to reinflate the lungs. Pre-clinical data suggest that pre-mortem administration of heparin might improve lung function by preserving endothelial homeostasis, but little evidence for clinical benefit Liver 30 Warm ischemia time limited to 20 min in suboptimal donors Higher mortality and increased incidence of graft failure and risk of ischemic cholangiopathy compared to DBD Greater donor age, and longer cold and warm ischemia are risk factors for poor outcome Database review suggested donor hypernatremia associated with poor post-transplant outcome, but recent evidence suggests no relationship Pancreas 30 Similar outcomes to DBD organs No organ-specific recommendations for potential donor management Heart 30 Heart DCD possible with rapid ex vivo perfusion and resuscitation of the heart prior to transplantation Pre-mortem echocardiography can assist in assessing suitability of the donor heart for transplantation No interventions that improve transplant function identified Ongoing Controversies in Organ Donation There are some lingering uncertainties that need ongoing clarification. We think there are 4 topics: 1) acceptance of the concept of brain death, including accommodation for decision makers not in agreement with brain death determination; 2) the seemingly never ending “whole brain” vs. “brainstem” death discussion; 3) pediatric guidelines as compared to adult guidelines; and 4) challenges in the interactions with Organ Procurement Organizations (OPO’s). Acceptance of Brain Death, Accommodation In recent years, numerous cases have received extraordinary publicity in which families have not been accepting of the concept of brain death. The most recently famous was the Jahi McMath case,1 in which the parents of an unfortunate brain dead adolescent refused to accept the diagnosis, and ultimately had her body, with the other organs still artificially supported, transported to an undisclosed facility in New Jersey for continued maintenance. The case brought to light the ambiguity or absence in most brain death policies as to how to deal with situations in which there is non-acceptance. Some brain death policies in the U.S. specifically provide guidance for “accommodation” in such situations, but the vast majority do not. Although some policies suggest giving additional time in these situations, very few give guidance about processes for reaching a resolution. Furthermore, very few policies address the specific situation in which the brain dead patient is pregnant and whether (and how) a body should be maintained in order to bring the fetus to a viable state - if possible at all. Guidance might be needed in these arenas. Brainstem vs. Whole Brain Death Brainstem death refers to the patient who has suffered a catastrophic neurological injury primarily to the brainstem, leading to a complete loss of neurological function. In the United Kingdom, there is a formal stance regarding a patient with brainstem death, in that they may be determined dead neurologically so long as all of the clinical criteria are met. However, in the United States and most of the rest of the world, there is no formal stance one way or the other regarding brainstem death. The Uniform Determination of Death Act3 is ambiguously written and left open to interpretation: brain death consists of the “irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brain stem…A determination of death is made with acceptable medical standards.” One could interpret this in two ways: 1) the “whole brain” must be dead, meaning, not just the brainstem; or 2) brainstem death is acceptable, so long as the “functions of the entire brain” are irreversibly ceased. And the phrase “acceptable medical standards” also leaves leeway for physicians to determine death with whatever standard/interpretation they deem appropriate. Brain death criteria in Children The pediatric guidelines were revised in 2011 under the auspices of the Society of Critical Care Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Child Neurology Society,4 and the adult guidelines revised in 2010 through the American Academy of Neurology.5 Key updates in the 2011 pediatric guidelines included specifications for the initial waiting period before conducting the first brain death examination, specialty of examiner, number of examinations, inter-examination interval, number of apnea tests, PaCO2 thresholds during apnea testing, and when an ancillary test may be used to reduce the inter-examination observation interval or assist with the diagnosis of brain death. The argument that more comprehensive testing produces greater certainty in the diagnosis of brain death and that patients may be mistakenly diagnosed as brain dead with only first examination is not supported by data — why would a 17-year-old be so different from an 18-year-old? Pediatric criteria have also mushroomed in countries outside the US. Without data it may be difficult to maintain these differences. Interactions with Organ Procurement Organizations With brain death determination and in situations of neurological catastrophes in which the patient is more suitable for DCD, there is often a challenging “decoupling” of the communication of the diagnosis and prognosis by the medical team and then the separate conversation with representatives for OPO’s who are involved in the process of discussing with families/decision makers about the possibility for organ donation. (ref) The intensivists – and particularly neurointensivists - caring for these patients are traditionally excluded from these secondary conversations, on the premise that they otherwise could be seen as having a potential conflict of interest or ulterior motive. This logic is flawed, however, as physicians are well aware of the fact that OPOs have been called expressly for this purpose, and most are committed to the concept of organ donation and the potential to save other lives when their own patient cannot be saved. This relationship and “hand off” needs to be further explored, and a more rational and collaborative approach realized for its potential. References: 1. Burkle CM, Sharp RR, Wijdicks EF. Why brain death is considered death and why there should be no confusion. Neurology. Oct 14 2014;83(16):1464-1469. 2. Criteria for the diagnosis of brain stem death. Review by a working group convened by the Royal College of Physicians and endorsed by the Conference of Medical Royal Colleges and their Faculties in the United Kingdom. Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of London. Sep-Oct 1995;29(5):381-382. 3. Uniform Determination of Death Act, 12 uniform laws annotated 589 (West 1993 and West supp (1997))(1980). 4. Nakagawa TA, Ashwal S, Mathur M, et al. Clinical report-Guidelines for the determination of brain death in infants and children: an update of the 1987 task force recommendations. Pediatrics. Sep 2011;128(3):e720-740. 5. Wijdicks EFM, Varelas PN, Gronseth GS, Greer DM. Evidence-based guideline update: Determining brain death in adults: Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. June 8, 2010 2010;74:1911-1918.