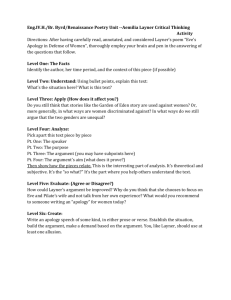

Argument Writing

advertisement