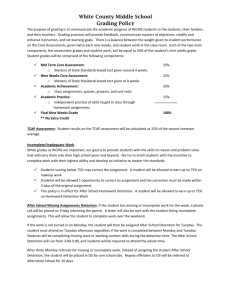

LAWS1205

Australian Public Law

Semester 1 2012

How to Use this Script:

These sample exam answers are based on problems done in past years. Since

these answers were written, the law has changed and the subject may have

changed. Additionally, the student may have made some mistakes in their answer,

despite their good mark.

Therefore DO NOT use this script by copying or simplifying part of it directly for use

in your exam or to supplement your summary. If you do so YOUR MARK WILL

PROBABLY END UP BEING WORSE! The LSS is providing this script to give you

an idea as to the depth of analysis required in exams and examples of possible

structures and hence to provide direction for your own learning.

Please do not use them for any other purposes - otherwise you are putting your

academic future at risk.

This paper is provided solely for use by ANU Law Students. This paper may

not be redistributed, resold, republished, uploaded, posted or transmitted in

any manner.

Page 1 of 6

ANU Law Student’s Society

© Copyright 2015, All Rights Reserved

Q2 Semester 1 2012.

Mark: 77

i)

The validity of ss 1-4 of the Act

Source of the Power to enact ss 1-4

The Cth legislature ahs the power to pass laws under s 1 fo the Cth constitution. The

problem here is that there is no express head of power in s 51 under which this Act

can be passed.

IF it can be shown, however, that it is merely legislation which is incidental to an

executive power, then the Act will be valid (s 51xxxix). This involves that such an

executive power exists for these purposes and that the legislation is incidental and

proportionate (Davis).

The Executive Power:

S 61 provides that the executive may undertake action for the execution and

‘maintenance’ of the Constitution. That section has been taken to include the

prerogatives (Davis) but also all executive action appropriate to the position of the

Cth in areas that relate to those responsibilities laid out in s 51, but also in those areas

appropriate to the character and status of the Cth as a national polity (Barton; Davis).

It must therefore be shown that the power here, to set up the ‘NVN’ is one appropriate

to the status of the Cth as a national government.

The subject being about the health of the nation and being a response to a ‘full-scale

epidemic’ throughout the country means that it is here a subject of a national and

widespread scale.

The action taken, of setting up clinics which administer a certain vaccination is,

arguably, adapted to that subject matter and a relevant action as it is necessary to

administer the particular policy (AAP).

There are, however, certain limitations to the power that need to be considered when

assessing this Act’s validity.

Limitations

The exercise of the nationhood, executive power must be one that is ‘peculiarly

adapted’ to the Cth executive and not otherwise be able to be carried out (AAP). It is

clearest where there is no competition with states (Pape) and must go beyond mere

convenience and there be a need (AAP).

The creation of the NVN Clinics and their administering of vaccinations is, arguably,

not needed here and the Cth is arguably not the only body to have the resources to do

so (Pape). On the facts, each state and territory has already created these clinics,

showing they have the capacity to cover this same subject and action. It could,

however, be argued that the Cth is the only body to do this quickly and given the

Page 2 of 6

ANU Law Student’s Society

© Copyright 2015, All Rights Reserved

short-term nature and measure (Pape) of the response it could be acceptable here. It

can also be likened to a crisis scenario as in Pape.

Given the executive power should be employed in times of protection (and

advancement) (Tampa) it is arguable that the executive power can here be found to

exist and its exercise ok.

The legislation being incidental

The legislation in its provision of the establishing of a network can be taken to

achieve that executive purpose and be reasonably proportionate. There are potential

issues with its coercive nature (s 5-8), but for this section (1-4), the legislation is

likely to be found valid and acceptable as per s 51xxxix and I would so advise the SA

Government. (V. Good analysis)

ii)

Advising John: ss 5-6

Again, the source of power is s 1 of the Cth Constitution.

Validity of ss 5-6:

As established in (i) here, the power to enact this Act was it being incidental to an

executive power founded under the idea of the ‘nationhood power’. The potential

problem with ss 5-6 is that they provide for coercive measures (it being an ‘offence’

and also detention measures). This is problematic because legislation incidental to the

nationhood power should usually not involve coercive measures (Pape), but rather be

restricted to a facultative measures and promotion and advancement (Tampa).

It could be argued that such coercive measures are appropriate here because there is a

need to isolate people and for there to be an incentive for people to isolate themselves

when they have the virus and stop the virus. On this view, the legislation, while

coercive, does remain reasonable and proportionate (Davis) [tick]. But also, given

that the symptons are only visible until the last 24 hours, there is an argument to be

had, that the coercive nature does go beyond what is reasonable in its affecting

possibly a large group of people who have not actually been exposed or did not know

they were being potentially exposed, as in John’s case here.

There are, therefore, arguments on both sides and it, arguably, goes beyond being

reasonably adapted and incidental. In any case, I would advise John that he is better

arguing that his detention was illegal because detention is usually to stem from a grant

of judicial power, which will now be discussed.

SS 5-6 validity re: legality of detention

Adjudgement and punishment of criminal guilt and powers of involuntary detention

under law is exclusive to and cannot be excluded from the judicial power of the Cth

(Lim).

The detention here was not authorised by a judicial order, but was carried out by

executive under legislation. This is problematic given that only Ch III courts (s 71)

can exercise judicial power, (such as punishment and detention) and non-judicial

power incidental to judicial power (Boilermakers). The executive legislature is,

Page 3 of 6

ANU Law Student’s Society

© Copyright 2015, All Rights Reserved

therefore, exercising judicial power which would usually point to John’s detention

being found illegal.

There are, however, exceptions to the rule that detention must involve judicial power.

As said in Lim and acknowledged at common law generally, quarantine [tick] may be

such an exception, which this arguably, is. But given that it is not clear yet that the

friend had contracted the virus, this is arguably not for real quarantine reasons and on

the Lim test, is not reasonably capable as being necessary. On this ground, the

detention could likely be found illegal.

But I would advise John that the Al-Kateb ruling will potentially help to find the

detention legal here even given its executive as opposed to judicial nature. That case

held that it is a matter of the law’s purpose not the punitive nature of the detention and

as long as that purpose is on foot, Ch III limitations (Boilermakers) will not be

breached. Al-Kateb also held that where that purpose is ‘purely protective’, detention

will not be classed as punitive.

Here, the law’s purpose was one of protection and its action of isolating by detention

remained on food with that purpose. I would advise John, whoever, that given the Alkateb case was in the context of aliens as opposed to citizens, that his case is not

hopeless and that if he pursues a reasonably necessity and need for judicial in put line

of argument here, that his detention could potentially be found illegal and the section

invalid.

iii)

There are two main elements here: i) does the minister have that power, and ii) is the

Museum bound by the legislation.

Source of the Minister’s power here:

The Cth Parliament can delegate power to the executive branch (Dignan), as has been

done here in s 7 [tick]. It cannot, however, abdicate power (Giris). If it can be shown

that power was abdicated s 7 will be invalid and the museum will not be required to

comply.

Was the power abdicated or delegated?

A number of factors will be considered: The subject matter here is not too wide or

uncertain (Dignan). Although there is some discretion in finding a penalty and

choosing the employers, the subject matter is constrained to those being infected and

to the virus (And is no where near to the powers conferred in Dignan).

Parliament seemingly has the power of ultimate control given it can still repeal or

amend the Act (Cobb&Co).

There are also provisions for supervision and accountability mechanisms (Cobb&Co),

given there is a tabling procedure (although it is for a short time) and the fact that

there is a possibility for disallowance by vote (Dignan). The Museum could

potentially argue that the period between tabling and the vote is too short, but this is

unlikely to be forceful and given most of the elements of delegation are in place, it is

likely to be found that the minister does have the power to make regulations [tick].

Page 4 of 6

ANU Law Student’s Society

© Copyright 2015, All Rights Reserved

Is the Museum bound by the Legislation?

Bropho held that it is a rule of statutory construction as to whether the Crown bound

by legislation, but that the Crown will usually be immune from burdensome

legislation. It must first have to be established as to whether the museum can be taken

as the crown.

Is the museum ‘the crown’? A number of factors will be considered:

i)

The presumption that the authority is not part of the Crown unless

parliament has expressly declared it is (Townsville) should first be

considered, but because the terms and purpose of the Act that founded the

body are not known not much analysis can take place here.

ii)

The establishment of museums and their running is arguably something

that govt. usually does and here given the fact that the majority of their

funding comes from the government demonstrates that it is quite closely

connected as a function as the next factor will also discuss.

iii)

There is a degree of ministerial and financial control (as above) here that

does indicate that the body is a regular part of government and this part of

the Crown here (Bradken). Its members are appointed by the minister and

its funding comes from government. Arguably, their degree of discretion

in spending money and running the museum separates them from being

found as part of the Crown, but this is unlikely to be determinative here.

iv)

The immunity privilege being claimed is arguably not something central to

its running of the museum (Townsville).

The Museum is likely to be found as part of the Crown on a balance of these factors.

Is it immune here?

This is a question of statutory construction as stated above (Bropho).

Here there are no express terms that bind the crown here or implied terms which

either extinguish or bind all employers or the Crown here (Bropho).

It is also unlikely that the purpose of the statute and its subject matter would be

wholly frustrated if the museum wasn’t here bound. However, given its purpose is in

response to a crisis and the crown generally now seeps into most aspects of life it

would potentially frustrate the Act’s purpose, if no statutory authority had to give

over the employees details, which is problematic (Bropho) [Tick]

The identity being purported to be bound is an employer which points towards it

being likely that it is bound given the presumption then becomes weak (Bropho).

The Museum is likely to be found, but it is likely a civil remedy or agreement will be

established as the crown is not usually subject to criminal penalties like the $50,000

fine (Doyle; Jackson).

iv)

Page 5 of 6

ANU Law Student’s Society

© Copyright 2015, All Rights Reserved

S 163 of the Cth Electoral Act provides for certain qualifications for members such as

needing to be an Australian citizen. The power to make those laws comes from ss 16,

34 and s 51(xxxvi) in the Cth Constitution, which provides a more broad ground.

S 44 of the Constitution provides more specific qualifications and restrictions for

members of parliament. I would advise Stephen that there are potentially two areas

that he can challenge Susan’s election. They are:

S 44(i): member cannot be a subject/citizen of a foreign power (confirmed in Skyes).

The problem here is that Susan is still a citizen of Vietnam, which means that she

potentially violates this section. SKyes held, however, that it turns on the

circumstances and that section will not be violated where the person has taken ‘all

reasonable steps to divest the citizenship’.

Although she has renounced the citizenship, it is unclear whether all reasonable steps

have been taken and no further action has been sought.

S 44(iv): incapable of being chosen if holds any office of profit under the crown.

Here problem: works at South Aus Department of Health and only on leave.

--Likely to be found to have breached section as in Skyes, given there he was a

teacher (similar-low exec position), on leave and in Victoria---which is similar here

and given the importance of independence, she will likely be found not qualified.

Though this is a matter for parliament (s 47).

But Stephen will likely be successful if he pursues these lines.

Page 6 of 6

ANU Law Student’s Society

© Copyright 2015, All Rights Reserved