Proposal - Bren School of Environmental Science & Management

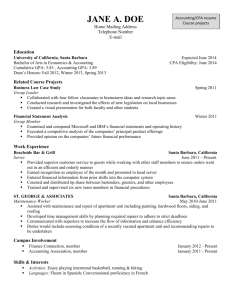

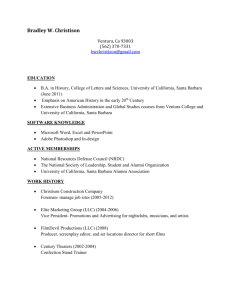

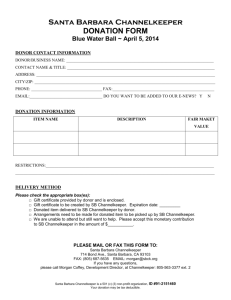

advertisement

Proposed Bren School Group Project 2015 – 2016 Project Title: Planning sustainable residential development in the South Coast: Assessing the carbon footprint of proposed housing projects using multi-scale analysis of the built environment Proposers: John Campanella: (805) 886-0654; johnsonofphil@gmail.com Smadar Levy, MESM student, The Bren School: (323) 449-0937; slevy32@gmail.com Background: In the past decade, widespread concern over global warming has prompted California to pass a number of bills requiring and incentivizing communities to adopt sustainability measures. The Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006 (AB 32) set the stage for much of this legislation by mandating the reduction of California’s GHG emissions to 1990 levels by 2020 and tasking the California Air Resources Board (CARB) to identify GHG sources and means of mitigation1. Senate Bill 375 (SB 375) arose from CARB’s finding that automobiles and light trucks alone contribute almost 30 percent of GHG emissions and declared change in land use patterns and improved transportation as essential for reducing vehicle emissions to meet GHG targets2. To ensure that these essential changes take place, the bill requires metropolitan regional transportation plans and local housing elements to include strategies to: 1) meet GHG reduction targets, and 2) provide sufficient housing for all income levels. Recent legislation further strengthens California’s support for the development of sustainable communities. Created in 2008 by SB 732, the Strategic Growth Council (SGC) executes the state’s Affordable Housing and Sustainable Communities (ASHC) Program. Beginning this year, the SGC will award approximately $120 million to projects for affordable housing, infill and compact transit-oriented development, as well as infrastructure connecting these projects to transit. More recently, in 2013, Senate Bill 743 altered the criteria by which CEQA evaluates traffic impacts “…to promote the state’s goals of reducing greenhouse gas emissions and trafficrelated air pollution, promoting the development of a multimodal transportation system, and providing clean, efficient access to destinations3.” Currently, traffic impacts are assessed through a project’s associated loss-of-service (i.e. reduced traffic flow), but will shift within the next two years to being assessed through a project’s associated vehicle-miles traveled (VMT), which serve as a proxy for GHG emissions. Collectively, this wave of legislation illustrates policy makers’ commitment to GHG emission reductions and a growing awareness of the importance of building environmentally and economically sustainable communities to combat global warming. 1 “Assembly Bill 32 - California Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006.” Accessed: 1/14/2015, http://www.arb.ca.gov/cc/ab32/ab32.htm. 2 “Senate Bill 375 - The Sustainable Communities and Climate Protection Act of 2008.” 3 “Senate Bill 743 - Environmental quality: transit oriented infill projects, judicial review streamlining for environmental leadership development projects, and entertainment and sports center in the City of Sacramento. (2013-2014).” Accessed 1/22/2015, http://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billVotesClient.xhtml Problem Statement: The South Coast’s current isolation from affordable residential communities presents a major opportunity to improve environmental and economic sustainability. The high cost of housing necessitates many employees to live a lengthy drive away in Ventura, Lompoc, or Santa Maria4; this contributes significantly to vehicle-related GHG emissions as well as traffic and congestion. In accordance with the sustainability initiatives of SB 375, Santa Barbara’s 2015 Housing Element draft prioritizes meeting affordable housing demand through high-density residential infill development with proximity to transit, job centers and public and community services5. Because Housing Elements are updated every eight years, it is essential the environmental benefits of this new policy be quantified so that future evaluations of housing policy can take GHG emission benefits into consideration. In addition, recent state legislation requires, or will soon require, the quantification of a project’s associated VMT to demonstrate compliance with CEQA (SB 743), and/ or win state funding (SB 732). Thus, there is an ever-growing need by South Coast planners for tools that quantify a building’s associated GHG emissions and VMT. How environmental costs and benefits of a residential building should be assessed remains a topic of debate. Increasingly, planning literature argues for a multi-scale approach that assesses a building within its urban context by incorporating building construction, operation, and usertransport costs6,7. For 2014-2015, its first year of project funding, the AHSC Program requires that applicants use the California Emissions Estimator Model (CalEEMod) 1 to estimate GHG emissions related to vehicle-miles traveled of proposed projects. This model incorporates a multi-scale approach and includes components that calculate construction, energy, and waterrelated emissions, as well as VMT-related emissions; however, the first three components will not be used in the assessment of proposed projects8. The CalEEMod1 is presented as an “interim methodology,” suggesting that a different methodology may be required in future years and points to continued contention over methodology. A comparison of currently available tools to assess GHG emissions associated with residential development could provide valuable insight on the usability and robustness of different models. Project Significance: This project will use multiple methodologies to assess the GHG emissions costs and relative savings of two residential projects in the South Coast as well as quantify GHG emission savings of higher density infill development relative to status quo development. In doing so, it will provide valuable feedback to South Coast leaders and community stakeholders regarding the environmental benefits of higher-density infill development. It will also provide the necessary 4 “Santa Barbara State of the Commute Summary,” Santa Barbara County Association of Governments. Accessed 1/19/2015: www.sbcag.org/uploads/2/4/5/.../state_of_the_commute_summaryv5.pdf 5 “Santa Barbara Housing Element,” City of Santa Barbara. Accessed 1/20/15: http://www.santabarbaraca.gov/services/planning/plan.asp 6 Emilia Conte and Valeria Monno, “Beyond the Buildingcentric Approach: A Vision for an Integrated Evaluation of Sustainable Buildings,” Environmental Impact Assessment Review 34 (April 2012): 31–40, doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2011.12.003. 7 André Stephan, Robert H. Crawford, and Kristel De Myttenaere, “Towards a Comprehensive Life Cycle Energy Analysis Framework for Residential Buildings,” Energy and Buildings 55 (2012): 592–600. 8 “Final Draft AHSC Program Guidelines,” Strategic Growth Council. Accessed 1/20/15: http://sgc.ca.gov/docs/AHSC_Proposed_Final_Guidelines.pdf VMT-related GHG emissions assessment needed to apply for project funding through the AHSC Program. By utilizing multiple methodologies to complete the assessments, this project will also allow comparison of available models that could be informative in developing standardized planning tools for California. Ultimately, the product of this project will provide South Coast’s planning community with customized models to assess GHG emissions associated with residential buildings that can be used to garner state funding, comply with new CEQA standards, optimize South Coast sustainability, and win stakeholder support for sustainable housing policies. Project Objectives: 1. Quantify the emissions savings of downtown, high-density infill residential development relative to residential developments in “bedroom communities” for Santa Barbara employers. 2. Compare multiple methodologies to assess GHG emission savings of at least two proposed residential projects. 3. Provide VMT-related GHG assessments of proposed residential projects that can be used by projects to apply for funding from the AHSC. Deliverables: A brief communications report assessing the benefits of downtown, high-density development based upon comparative analysis of downtown development versus averaged county residential emissions. A customized multi-scale framework to assess emission contributions of residential buildings that can be used by South Coast planners to guide future decisions about development. A review and recommendations for improvement of currently available tools to assess GHGemissions of residential building projects. Approach and Available Data: To quantify the emissions savings of downtown, high-density infill development relative to current residential development (objective #1), GHG emissions associated with completed infill development projects will be compared with GHG emissions associated with completed residential developments in Ventura, Lompoc, and/or Santa Maria. A software tool developed by Stephan et al. will be used that can assess the multi-scale energy cost of residential buildings as well as districts9. Inputs include embodied energy costs (i.e. energy costs of materials used to construct the building and associated infrastructure), building operational costs, and transport energy costs to present an assessment that integrates building and city-scale energy costs. This framework will be one of the methodologies used to assess the GHG-emissions associated with two residential projects, along with the CalEEMod1 (objective #2). The CalEEMod1 will also be used as directed by AHSC Program guidelines to determine VMT-related GHG emissions specifically (objective #3). The model by Stephan et al. provides far more inputs than the CalEEMod1 so data obtained should be more than sufficient for the CalEEMod1. Data available and data required by the Stephan et al. model are outlined below for each cost category: 9 Stephan, Crawford, and De Myttenaere, “Towards a Comprehensive Life Cycle Energy Analysis Framework for Residential Buildings.” Embodied energy costs will be calculated primarily based on building materials and infrastructure density data. For objective #1, building materials for a number of randomly selected county developments will be averaged to represent typical South Coast residential buildings. For objective #2, building material estimates proposed for a given project will be used. Location-specific infrastructure density data will be obtained using Google Earth. Operational energy costs will be calculated based on local user utility data from management and/or utility companies. To help planners select projects that optimize GHG emissions, operational energy costs will include building feature parameters, such as building size, number of units, number of occupants, and proposed rent because income-level significantly affects operational costs10. Transport energy costs will be calculated based on user transport behavior and energies associated with different transport modes. A survey will be conducted to obtain commuter data for South Coast residents in the residential project neighborhoods. Available regional commuter data will be used to calculate transport energy costs for typical residential development. References: 1. “Assembly Bill 32 - California Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006.” Accessed: 1/14/2015, http://www.arb.ca.gov/cc/ab32/ab32.htm. 2. “Senate Bill 375 - The Sustainable Communities and Climate Protection Act of 2008.” 3. “Senate Bill 743 - Environmental quality: transit oriented infill projects, judicial review streamlining for environmental leadership development projects, and entertainment and sports center in the City of Sacramento. (2013-2014).” Accessed 1/22/2015, http://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billVotesClient.xhtml 4. “Santa Barbara State of the Commute Summary,” Santa Barbara County Association of Governments. Accessed 1/19/2015: www.sbcag.org/uploads/2/4/5/.../state_of_the_commute_summaryv5.pdf 5. “Santa Barbara Housing Element,” City of Santa Barbara. Accessed 1/20/15: http://www.santabarbaraca.gov/services/planning/plan.asp 6. Emilia Conte and Valeria Monno, “Beyond the Buildingcentric Approach: A Vision for an Integrated Evaluation of Sustainable Buildings,” Environmental Impact Assessment Review 34 (April 2012): 31–40, doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2011.12.003. 7. André Stephan, Robert H. Crawford, and Kristel De Myttenaere, “Towards a Comprehensive Life Cycle Energy Analysis Framework for Residential Buildings,” Energy and Buildings 55 (2012): 592–600. 8. “Final Draft AHSC Program Guidelines,” Strategic Growth Council. Accessed 1/20/15: http://sgc.ca.gov/docs/AHSC_Proposed_Final_Guidelines.pdf 9. Stephan, Crawford, and De Myttenaere, “Towards a Comprehensive Life Cycle Energy Analysis Framework for Residential Buildings.” 10 John E. Anderson, Gebhard Wulfhorst, and Werner Lang, “Energy Analysis of the Built environment—A Review and Outlook,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 44 (April 2015): 149–58, doi:10.1016/j.rser.2014.12.027. 10. John E. Anderson, Gebhard Wulfhorst, and Werner Lang, “Energy Analysis of the Built environment—A Review and Outlook,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 44 (April 2015): 149–58, doi:10.1016/j.rser.2014.12.027. SUPPORTING MATERIALS Budget and justification Available funds - $1,300 (Bren School): Research and report expenses - $1,500 (John Campanella): Travel expenses, workshops, other expenses Contact List (Partial) (1) Mike McCoy, Executive Director, Strategic Growth Council – mike.mccoy@sgc.ca.gov | Coordinates Affordable Housing and Sustainable Communities Program Funds (cap and trade) (2) Chris Ganson, Senior Planner, Governor’s Office of Planning and Research – chris.ganson@opr.ca.gov | Sets policy and receives public comments on the use of VMT in CEQA traffic impact analysis (3) Peter Imhoff, Deputy Director Planning, Santa Barbara County Association of Governments – pimhof@sbcag.org | Responsible for producing Sustainable Communities Strategy and Regional Transportation Plan (4) Rob Fredericks, Deputy Executive Director, Housing Authority of the City of Santa Barbara – rfredericks@hacsb.org | Responsible for affordable housing financing/operations for the City Housing Authority (5) John Polanskey, Housing Authority of the County of Santa Barbara – johnpolanskey@hasbsrco.org | Responsible for affordable project development for the County Housing Authority (6) Ron Biscaro, V-P of Project Management, Bella Riviera Workforce Homes, Santa Barbara Cottage Hospital – rbiscaro@sbch.org | Project Manager for the completed Bella Riviera moderate-middle income employee housing purchase program in the City of Santa Barbara (7) Craig Minus, Director of Project Management, The Towbes Group – cminus@towbes.com | Responsible for market rate rental projects in the City of Goleta (8) Bill McReynolds, Vice-President Development, City Ventures – bill@cvassets.com | Responsible for infill workforce for-sale projects in the City of Santa Barbara and Goleta Various South Coast Planning Department Personnel – City of Santa Barbara, County of Santa Barbara, City of Goleta, City of Carpinteria