Allergic Rhinitis & Asthma Case Study: Diagnosis & Management

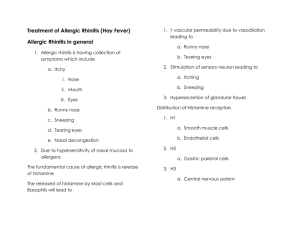

advertisement

Dr. Sailesh Gupta, MD DCh Practicing Pediatrician, Mumbai; Honorary Secretary General, Central office of Indian Academy of Pediatrics, Past Secretary, IAP Respiratory Chapter, Past Editor, Pulmonology Update, Bulletin of the IAP Respiratory Chapter, Past President, IAP Mumbai. A child with allergic rhinitis Case presentation A five year-old boy with no family history of atopy, who had been in reasonably good health until the age of three years, was presented to the pediatrician because of sneezing, rhinorrhea, blockage of nose, and occasional nasal bleeding. The patient also complained of cough, headache, malaise and redness of the eyes with watering. The symptoms had been occurring intermittently for the past two years, and exhibiting no seasonal variation, but usually got exacerbated in a pollen season and/or smoky environment. Consequently, the child had been experiencing difficulty in breathing, a feeling of tightness in the chest, wheezing and worsening of cough at night, and poor sleep. He had begun to be irritable at home and his kindergarten class. Examination findings The child was well oriented, though uncooperative and irritable, appeared normal in developmental domains, and had no obvious external abnormality. ENT examination: Rhinitis, swelling of nasal mucosa and slight deviation of the nasal septum Chest examination: Mild reduction of air entry Systemic examination: The cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and central nervous system examination was normal Investigations X-ray for sinuses: No evidence of sinusitis X-ray of chest - Normal Allergy testing: Skin prick tests with a standard panel of allergen extracts: Positive for dust mite antigen, pollen, and fungus Blood examination: Eosinophils - 8 - 9 %. Overall lymphocytosis Serum immunoglobulin concentrations: IgA - 82 mg/dl (normal: 0-163 mg/100 ml) IgM - 168 mg/dl (normal: 24-88 mg/100 ml) IgG – 835 mg/dl (normal: 519-1255 mg/100 ml) IgE total - 6.35 kU/l. (normal: 1-161 kU/l) Raised Diagnosis Based on the characteristic history, symptoms, and evaluation, the child was diagnosed as a case of intermittent mild to moderate allergic rhinitis with intermittent asthma. Management The patient was prescribed intranasal corticosteroid, and a leukotriene receptor antagonist, and an oral bronchodilator syrup containing terbutaline. In addition, the parents were advised to protect the child from pollen and smoke, and avoid substances and environment that they considered could exacerbate the child’s symptoms. On follow-up visit, the patient reported considerable improvement in his symptoms, and, was advised to continue the treatment for another week. Later, he reported having control of symptoms with no exacerbation, and correspondingly improved quality of life. The patient was advised to continue allergen avoidance; the leukotriene antagonist and intranasal steroid were continued for six weeks, and the oral bronchodilator was given for cough, when necessary. Discussion Allergic rhinitis is the most prevalent form of chronic rhinitis in children, driven by allergic inflammation, and commonly associated with other atopic diseases, such as asthma and atopic eczema. The disease is caused by an inflammatory process related to IgE-mediated reaction allergens to which the subject is sensitized.1 While the main allergens are primarily aeroallergens (house dust mite, and tree, grass and weed pollen), it is not unexceptional to experience symptoms of allergic rhinoconjunctivitis together with food allergy and oral food allergy Nasal block is the main symptom syndrome, especially in infants and toddlers.2 affecting children with allergic A recently proposed classification of allergic rhinitis based on the rhinitis duration and severity of clinical symptoms takes into consideration both the quality of life and the possible impact of the symptoms on school, work and free-time activities. The quality of life of the children affected by allergic rhinitis is severely compromised by frequent night awakenings, easy fatigue, defects of language and irritability, which can have a negative influence on learning abilities. Nonetheless, it has a negative impact on the quality of life of the whole family owing to its interference on social life, and financial costs. 1 Nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, sneezing, and pruritus of the eyes and nose are troublesome symptoms in patients with allergic rhinitis (Figure 1). In particular, the importance of congestion is noted in children and adults. As emphasized by the recent publication of the Pediatric Allergies in America survey, congestion is the main symptom affecting children with allergic rhinitis.3,4 Further, depending on the symptom frequency, it is classified as intermittent or persistent and according to the intensity of the symptoms, as mild or moderate-to-severe (table 1).5 Figure 1. Classic symptoms of allergic rhinitis Classic symptoms of allergic rhinitis Sneezing Pruritus Rhinorrhea Nasal obstruction Table 1. Classification of allergic rhinitis Allergic rhinitis and asthma Allergic rhinitis is associated with asthma in nearly 40 percent of cases, while nearly 75 percent patients with asthma have allergic rhinitis, and, thus, making it essential to treat both conditions together. Indeed; it is not considered an isolated disease since the nasal mucosa inflammation involves paranasal sinuses and lower airways, thus worsening the asthmatic symptoms.1 Evidence suggests that for better asthma control rhinitis has to be managed. Despite anatomically related differences existing between these two clinical conditions, allergic rhinitis and asthma, share a pathogenetic mechanism represented by an inflammatory pattern wherein many upper airways cells and mediators are the same as those involved in lower airway disease.6 Thus, they seem to be a different phenothypical expression of a common immunological process. Biomarkers in asthma and allergic rhinitis An applicable biomarker represents a physical sign or laboratory measurement that can serve as an indicator of biological/pathophysiological processes or as a response to a therapeutic intervention, and possesses the characteristics of clinical relevance (sensitivity and specificity for the disease) and is responsive to treatment effects, in combination with simplicity, reliability and repeatability of the sampling technique. Currently, there are numerous biomarkers for allergic rhinitis and asthma that can be obtained by non-invasive or semi-invasive airway sampling methods meeting at least some of these criteria. Allergic rhinitis is characterized by Th2 polarized immune response, such as increased IL-4 and reduced IFN-gamma production; also, there exists a significant correlation between IgE levels and allergy severity. Further, in clinical practice, such biomarkers can provide complementary information to conventional disease markers, including clinical signs, spirometry and PC (20) methacholine or histamine, and, therefore, can aid in establishing the diagnosis, in staging and monitoring the disease activity/progression, or in predicting/monitoring of a treatment response. Evidently, reliable and noninvasive biomarkers would be valuable, particularly in (young) children. Besides diagnostic purposes, biomarkers can also be used as (surrogate) markers to predict a (novel) drug’s efficacy in target populations. When implementing biomarkers in allergic rhinitis and asthma, it is important to consider the heterogeneous nature of the inflammatory response which should direct the selection of adequate biomarkers. At the same time, some biomarker sampling techniques await further development and/or validation, and should, therefore, be applied as a “back up” of established biomarkers or methods. Moreover, some biomarkers or sampling techniques are less suitable for (very young) children. Thus, in practice, a decision needs to be made on a case by case basis pertaining to what biomarker is adequate for the target population or purpose pursued. This is also the driving force behind continued search for a perfect biomarker, and future development of more sophisticated sampling methods and quantification techniques, for example-- omics and biomedical imaging, will enable detection of adequate biomarkers for both clinical applications. Source: 1. Diamant Z, Boot JD, Mantzouranis E, et al. Biomarkers in asthma and allergic rhinitis. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2010;23(6):468-81. 2. Ciprandi G, De Amici M, Tosca MA, et al. Sublingual immunotherapy affects specific antibody and TGFbeta serum levels in patients with allergic rhinitis. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2009;22(4):1089-96. 3. Ciprandi G, De Amici M, Tosca MA, et al. Immunoglobulin production pattern is allergen-specific in polysensitized patients. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2009;22(3):809-17. Treatment – the need for decongestants While the mainstay of treatment is environment modification, most children would require drug therapy for symptom control, which includes intranasal corticosteroids, antihistamines, leukotriene antagonists and decongestants. Short-term (up to 3 months) use of intranasal corticosteroids has not been associated with any significant local or systemic side effects.2 Nonetheless, while intranasal corticosteroids are an integral part of the clinical protocol, oral decongestants would be particularly beneficial for their symptomatic relief, considering the fact that congestion is the main symptom affecting children with allergic rhinitis. In fact, oral treatment is best in chronic cases of nasal congestion, such as allergic rhinitis, or when decongestion of mucosa away from the nose is required.7 Hence, phenylephrine (decongestant) and bromhexine (mucolytic) may be particularly helpful in symptomatic treatment of allergic rhinitis. Oral decongestants are known for their property of reducing nasal congestion and thus can attenuate drainage effectively, nasal congestion responds quite well to decongestants regardless of its cause. Phenylephrine is an orally administered sympathomimetic nasal decongestant that causes powerful vasoconstriction by stimulating the post-synaptic alpha receptors.8 It causes vasoconstriction of the nasal blood vessels, thus decreasing blood flow to the sinusoidal vessels, and leading to decreased mucosal edema – the basis of its decongestant effectiveness. Furthermore, the drug, being a direct selective α-adrenergic receptor agonist, does not cause the release of endogenous noradrenaline, unlike pseudoephedrine, and, therefore, is less likely to cause central nervous system stimulation, insomnia, anxiety, irritability, and restlessness. Bromhexine is another potential therapeutic agent meant for symptomatic relief in allergic rhinitis and asthma, and respiratory disorders associated with viscid or excessive mucus. The drug also has antioxidant properties, and supports the body’s own natural mechanisms for clearing mucus from the respiratory tract. In effect, bromhexine exhibits a secretomotoric effect - it increases production of serous secretion in the respiratory tract, and make the phlegm thinner and less sticky, thus enhancing the mucus transport by reducing its viscosity, and also by activating the ciliated epithelium. Conclusion Allergic rhinitis affects 10-25% of the population, making it the most prevalent allergic disorder, and similar to other diseases results in direct, indirect and hidden costs.9 Further, with its impact on the quality of life of the affected, allergic rhinitis is more than just sneezing and an itchy nose.10 Since avoidance of allergens often proves to be difficult in practice; pharmacotherapy may generally be required in all cases.11 While intranasal corticosteroids have direct position in management, oral decongestants would be helpful particularly in children, as congestion is the main symptom affecting children with allergic rhinitis. References 1. Miraglia Del Giudice M, Marseglia A, et al. Allergic rhinitis and quality of life in children. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2011;24(4 Suppl):25-8. 2. Richter D. Allergic rhinitis in children. Acta Med Croatica. 2011;65(2):163-8. 3. Sardana N, Craig TJ. Congestion and sleep impairment in allergic rhinitis. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2011;29(4):297-306. 4. Meltzer EO, Blaiss MS, Derebery MJ, et al. Burden of allergic rhinitis: results from the Pediatric Allergies in America survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:S43–70. 5. Camelo-Nunes IC, Solé D. Allergic rhinitis: indicators of quality of life. J Bras Pneumol. 2010;36(1):124-33. 6. Braido F, Baiardini I, Lagasio C, et al. Allergic rhinitis in asthma. Panminerva Med. 2011;53(2):97-107. 7. Empey DW, Medder KT. Nasal decongestants. Drugs. 1981;21(6):438-43. 8. Pawankar R. Allergic Rhinitis and Asthma: The Link, The New ARIA Classification and Global Approaches to Treatment. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;4(1). 9. Rutkowski R, Kosztyła-Hojna B, Rutkowska J. Allergic rhinitis--an epidemiological, economical and social problem of the XXI century. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2008;76(5):348-52. 10. Borres MP. Allergic rhinitis: more than just a stuffy nose. Acta Paediatr. 2009 Jul;98(7):108892. 11. Kemp AS. Allergic rhinitis. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2009;10(2):63-8. Success Story Before mentioning about 'my' mantra's for success, i would like to define success. Success means differently to different people. To my mind success is being able to do exactly what one desires to do, in the manner and at a pace that one is happy with, without the need to 'prove' oneself, without compromises that one is unwilling to make, and without external influences and controls. Success happens every day, in small and big ways, in short and long moments to people from all walks of life. Similar to the individualistic nature of success, the mantras for success are also very individualistic. Different persons achieve the same measurable result or reach the same goal through different means or paths. The effect of success also varies. It brings different levels of happiness and contentment to differently natured persons. My mantras for success are 1) Following the intuitive dictates of my 'heart' rather than the studied counsel of my 'intellectual mind' in choosing my goals, objectives, and projects 2) Working to my best capacity on everything I take up 3) Attempt to achieve excellence in whatever I do 4) Be my own best judge, and aim to satisfy myself more than anyone else 5) The result of my efforts is important to me, and i find it hard not to focus on getting the desired and best result in the smallest of tasks I am not sure i have reached any 'level' that should satisfy me and make me happy. Life is in a constant flux, and it is wise to consider every 'level' important enough to deserve one's best attention. My biggest challenges in achieving my personal and career milestones came from within me and sometimes from the attitudes of people that I met along the way. Not endowed with a natural sense of self confidence, i battled self doubt several times. I also sometimes dealt with less than flattering assessments of my abilities by my others, but understood through experience that the best assessment whether good or bad, was always mine One must remember that success and failure are flip sides of the same coin and just as everything else in life, including life itself, are temporary and fleeting. The focus should be on survival and 'going-on' in life rather than the achievement of 'ultimate' success or goal, for there isn't an ultimate goal except death. One never really changes inside and one should never attempt to do so artificially simply to measure up to one's external success. One should not force one's success on others around and success should not be allowed to create walls between individuals and alienate loved ones, for success is temporary, an artificial and penetrable shield to hurts and pains of the world. If one's external success is stripped away, one is only a soft, vulnerable and alone human being. The strength and confidence should be inside of us, and not on the outside. True success lies in the ability to stand alone and unafraid in the face of the worst natural or human adversity. The most challenging phases in my career have not been the development of my practice or my rise in the hierarchy of my professional organisation, but the inner turmoil faced by me at various stages in my career when i had to follow set norms in practice and administrative responsibilities as against the intuitive paths i would have preferred to follow. At such times, for general good, i had to put my instincts on a back burner and work as per the calculated advices of my thinking mind. Such instances have been few, but significant for the distress they caused me. My advice to young Paediatricians is 1. Treat every child as your own and not as a 'patient' or a 'case' 2. Only think of the patient and never about yourself when you advise treatment. You will be taken care of very well by the universe 3. Never do harm, even if you can't sometimes do good 4. Never make money an issue in your relationship with the patient 5. While you may be seen as akin to God, remind your patients (parents) that their expectations of you should be within reasonable limits 6. Seek to educate parents; focus on preventive rather than curative medicine; provide holistic management to the entire family of humans rather than disease based treatment of your child patient