"Arguments for God" handout.

advertisement

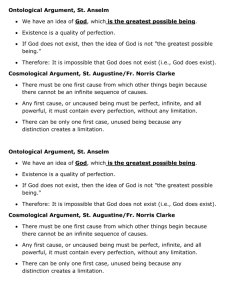

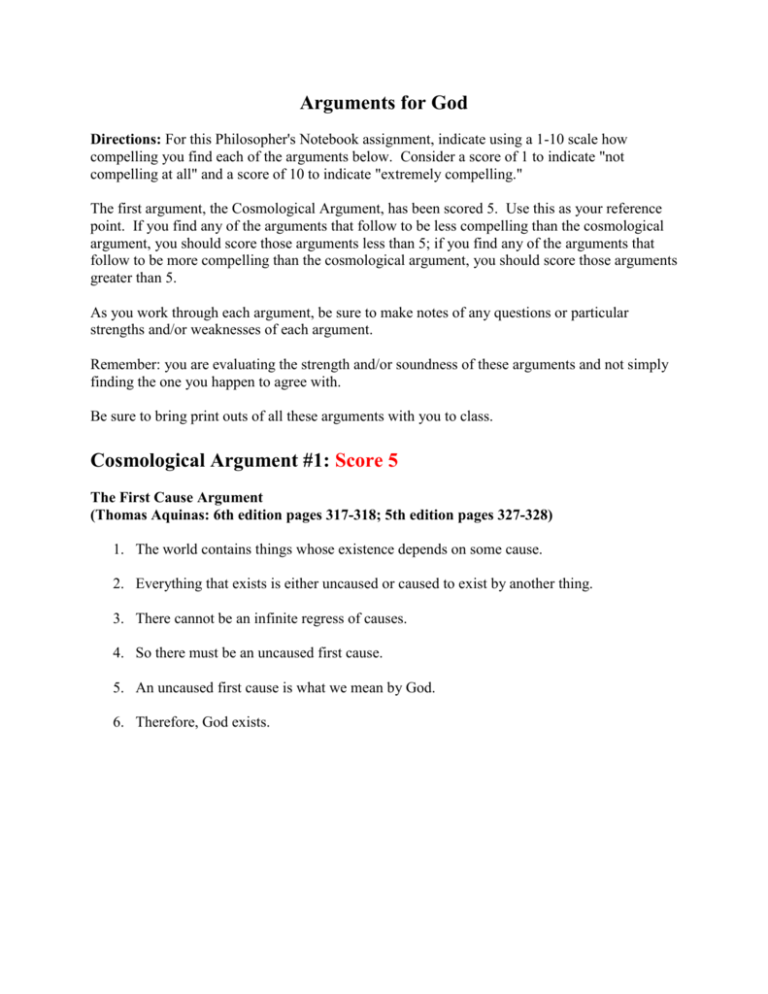

Arguments for God Directions: For this Philosopher's Notebook assignment, indicate using a 1-10 scale how compelling you find each of the arguments below. Consider a score of 1 to indicate "not compelling at all" and a score of 10 to indicate "extremely compelling." The first argument, the Cosmological Argument, has been scored 5. Use this as your reference point. If you find any of the arguments that follow to be less compelling than the cosmological argument, you should score those arguments less than 5; if you find any of the arguments that follow to be more compelling than the cosmological argument, you should score those arguments greater than 5. As you work through each argument, be sure to make notes of any questions or particular strengths and/or weaknesses of each argument. Remember: you are evaluating the strength and/or soundness of these arguments and not simply finding the one you happen to agree with. Be sure to bring print outs of all these arguments with you to class. Cosmological Argument #1: Score 5 The First Cause Argument (Thomas Aquinas: 6th edition pages 317-318; 5th edition pages 327-328) 1. The world contains things whose existence depends on some cause. 2. Everything that exists is either uncaused or caused to exist by another thing. 3. There cannot be an infinite regress of causes. 4. So there must be an uncaused first cause. 5. An uncaused first cause is what we mean by God. 6. Therefore, God exists. Cosmological Argument #2: Score The Principle of Sufficient Reason Argument (Richard Taylor: 6th edition pages 320-324; 5th edition pages 331-334) 1. Something “created” is something contingent on its creator—i.e. the created thing depends on a creator for its existence. 2. A contingent thing cannot be its own cause—i.e. something cannot create itself. 3. A contingent thing may or may not exist—i.e. it is finite, destructible, and not necessary. 4. All the things in the world and the world itself are contingent—i.e. we can imagine an alternative world in which conditions are different and exclude the existence of any individual thing that exists in our world. 5. A necessary thing does not depend on anything outside of itself for its existence and nothing can prevent it from existing. 6. A necessary thing is uncaused, indestructible, self-sufficient, and independent—i.e. it is necessary in the sense that there is no way for it to not exist. 7. The idea of God is the idea of a perfect being that has always been, that will always be, that is omnipotent and omnipresent, and that is the source of all things. 8. There can be only one necessary thing in the universe. 9. The world is contingent on a necessary thing. 10. God is the necessary thing/being on which the existence of the world depends. Teleological Argument: Score The Argument from Design (William Paley: 6th edition pages 328-329; 5th edition pages 338-339) 1. The universe exhibits an apparent design—that is, an ordering of complex parts that function in a machine-like or organism-like universe. 2. The individual parts serve a function as a means to the fulfillment of intelligible goals, ends, or purposes. 3. A purposive, intelligent will is the cause of similar design and order in things we discover in the world. 4. Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that the universe and the complex interdependencies of its individual elements was caused by a purposive, intelligent will. Ontological Argument: Score The Being than which Nothing Greater Can Be Conceived Argument (St. Anselm: 6th edition page 337; 5th edition page 347) 1. I have, within my understanding, an idea of God. 2. This idea of God is the idea of the greatest possible being. 3. A being is greater if it exists in reality than if it exists only in the understanding. 4. If God exists in the understanding alone, then a greater being can be conceived, namely, one that also exists in reality. 5. But premise #4 is a contradiction, for it says I can conceive of a greater being than the greatest conceivable being. 6. So if I have an idea of the greatest conceivable being, such a being must exist both in my understanding and in reality. 7. Therefore, God exists in reality. Perfection Argument: Score Descartes’ Argument from Perfection (Descartes: 6th edition pages 201-203; 5th edition pages 83-85) 1. A being that doubts is an imperfect being (because a perfect being would have full knowledge, hence no room for doubt). 2. I doubt; therefore, I am an imperfect being. 3. Yet I could know that I am imperfect only by having the concept of perfection; therefore, I do have the concept of perfection. 4. I could not have received the concept of perfection from something imperfect; therefore, my concept was not derived from myself. 5. Therefore, my concept of perfection was derived from something that is perfect. 6. Only God is perfect (i.e. God is perfection), so I derived my concept of perfection from him, and therefore, he exists. Pragmatist Argument #1: Score The Wager (Blaise Pascal: 6th edition pages 342-343; 5th edition pages 352-353) 1. God either exists or he/she/it does not exist. 2. If God exists, we are his/her/its creation and are responsible for living in accordance with his/her/its plan. 3. If God exists and we live rightly (i.e. in accordance with his/her/its plan), then we will reap the great reward of eternal life. 4. If God does not exist, we are completely free and autonomous and can live according to our own desires since the only rewards are the rewards we receive on earth. 5. Choosing to believe in God risks the loss of complete freedom for the possibility of eternal life. 6. Choosing to not believe in God risks the loss of eternal life for the benefits of finite earthly rewards. 7. It is smarter to risk the small sacrifice of loss of total autonomy for the possibility of eternal life than to risk the loss of eternal life for the benefit of finite earthly rewards. 8. Therefore, one should believe God exists. Pragmatist Argument #2: Score The Living, Forced, Momentous Choice (William James: 6th edition pages 346-347; 5th edition pages 356-357) 1. A “living” choice is a choice about something relevant; a “dead” choice is a choice about something irrelevant. 2. A “forced” choice is a choice one must make (i.e. not choosing is results in a de facto choice); an “avoidable” choice is a choice one can postpone or avoid without a de facto choice occurring. 3. A “momentous” choice is a choice of great consequence; a “trivial” choice is a choice of little or no consequence. 4. When faced with living, forced, momentous choices, we should always seek objective, rational certainty to guide our choice; when objective, rational certainty is not unavailable, we should make choices that are the most subjectively and pragmatically appealing. 5. The choice to believe or not believe God exists is a living choice because you are aware of the opportunity to decide whether or not to believe or not believe in an omniscient, omnipresent God. 6. The choice to believe or not believe God exists is a forced choice because not choosing is a de facto choice to not believe God exists. 7. The choice to believe or not believe God exists is a momentous choice because your choice will determine the shape of at least your earthly life and potentially your eternal life. 8. It is not possible to have objective, rational certainty to guide us in choosing to believe or not believe God exists, so one must choose what is most subjectively and pragmatically appealing. 9. It is more subjectively and pragmatically appealing to believe God exists than to believe God does not exist. 10. Therefore, God exists.