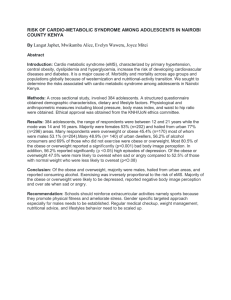

1.2. Childhood obesity, protein metabolism and lean

advertisement