File

advertisement

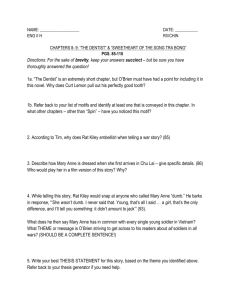

Mak 1 JoAnna Mak Pd. 3 Lang The Disintegration of Gender Roles: War and the Woman In the late 1960s, the Selective Service held two lotteries for men born between 1944 and 1950 to serve in the Vietnam War. The draft did not include women; of the women who did serve in the war, nine out of ten were nurses, and all had volunteered to serve. During this period of time, women were only beginning to become prominent members of society, fighting their way into American culture from a history of submission and passivity. Vietnam veteran Tim O’Brien questions the traditional expectations of women in his short story collection The Things They Carried, in which he addresses the relationship between gender roles and labels, and explores the effect of war on the dominance of social conventions through Mary Anne, a young girl who moves to Vietnam to stay with her boyfriend. At first, Mary Anne takes light enjoyment in wartime activities but gradually immerses herself into the land, eventually disappearing from society altogether. In “Sweetheart of the Song Tra Bong,” O’Brien reveals Mary Anne’s evolution from alluring to untamed through depicting her initial interest in war practices, growing indifference towards her image, and infatuation with Vietnam, suggesting that war distances individuals from the confines of social labels. O’Brien describes Mary Anne’s insatiable curiosity about war practices to foreshadow her transformation from seductive to unfettered, exploring how war renders stereotypes unfitting, and thus obsolete. O’Brien describes how Mary Anne enjoys “roam[ing]” around the quarters “asking questions,” juxtaposing the image of a flirtatious girl with that of a hungry predator (91). By injecting a sense of aggression into Mary Anne’s inviting attitude, O’Brien indicates that war nullifies the social constructs of sexual desire in crafting a character that seems to follow preconceived notions of femininity, yet ultimately contradicts them. The soldiers, amused by Mak 2 Mary Anne’s interest in the war effort, refer to her as their “own little native,” hinting at the general norm of female submission to men, yet also suggesting a primal independence to Mary Anne’s personality (91). While the soldiers want to hold her to the conventions of femininity, they also acknowledge that Mary Anne cannot be restricted to a stereotype, furthering the idea that war revokes the authority of labels in dictating social conduct. Accustomed to admiring women for their appearances, another soldier jokes that Mary Anne has “D-cup guts” to indicate his surprise at her willingness to aid the men, as an attractive woman is not typically associated with audacity, but with sex (92). The conflicting connotations associated with sex appeal and boldness demonstrate how war reduces the capacity of labels to categorize individuals. As Mary Anne begins to evolve from captivating to wild, her interest in the war grows, whereas her attentiveness to her appearance starts to wane. Mary Anne transitions from attractive to free-spirited as she begins to place less emphasis on her sex appeal, indicating that war releases individuals from the societal standards of beauty. Mary Anne expresses her detachment from material beauty as she “cut[s] her hair short” and covers it in a “dark green bandanna,” discarding her femininity and replacing it with the earthy atmosphere of the Vietnam forests, in which she finds solace (94). Through Mary Anne’s severing of ties to her former environment, O’Brien suggests that war minimizes a person’s interest in superficial matters, heightening their true passions. Although material accessories are often used to characterize people as appealing, Mary Anne does not choose to associate herself with sex, instead adorning a “necklace of human tongues” as a barbaric representation of her independent, untamable character (106). Through her wild choice of jewelry, O’Brien insinuates that war allows individuals to deviate from the traditional ideas of physical appeal. However, O’Brien emphasizes that Mary Anne does not become a new person but merely presents herself Mak 3 under different tones, describing how her voice appears to “reorganize itself” with a deeper quality to indicate her decreased focus on materialism and emerging sense of individuality (95). Mary Anne’s desire to abide by society’s definition of beauty ultimately weakens as she reframes her values, emphasizing that war minimizes the significance of physical appeal. As she becomes more and more engrossed in the war, Mary Anne is spellbound by the land, not only expressing disinterest in beauty but also taking action in defiance of gender norms. O’Brien suggests that war distances individuals from societal values and conventions as Mary Anne becomes captivated with Vietnam, ultimately transitioning from ravishing to feral. Mary Anne’s desire to “eat” the land characterizes war as alluring, in stark contrast to its reputation as an unwelcome and damaging affair (106). Furthermore, O’Brien states that Mary Anne wants to “become intimate with danger” to imply that she lusts after the exhilarating uncertainty of death, whereas most people would balk at the thought of jeopardizing their lives (109). The disparity between society’s disdain for threats to order, such as conflict or peril, and Mary Anne’s hunger for the dangerous thrills of Vietnam suggests that war releases individuals from societal perspectives, allowing them the autonomy to form opinions deviant from the norm. Mary Anne’s unusual enthrallment with Vietnam and the pleasures of danger also presents a twist on gender customs: although women are typically known to be pursued, Mary Anne is now portrayed as the aggressor, desiring a connection with the land. In constructing a situation in which female gender norms are reversed, O’Brien implies that war strips women of the expectation to be passive, minimizing the authority of labels over individuals. In Mary Anne’s transition into an independent and adventurous person, O’Brien reinforces the idea that war distances individuals from social expectations. Mak 4 In “Sweetheart of the Song Tra Bong,” O’Brien portrays Mary Anne’s evolution from enthralling to wild to suggest that war distances individuals from the confines of social labels through his depiction of her initial interest in war practices, disinterest in materialism, and infatuation with Vietnam. Although the shocked soldiers view Mary Anne’s transformation as negative, O’Brien hints that the soldiers are uncomfortable with Mary Anne’s change not necessarily because her new personality is distasteful, but due to the fact that she defies categorization into society’s constructed expectations. In depicting their unease, O’Brien criticizes society for imposing these stereotypes upon itself; he asserts that labels do not provide insight on personal character, but restrict the ability of humans to view each other as full-fledged individuals.