Daubert Brief

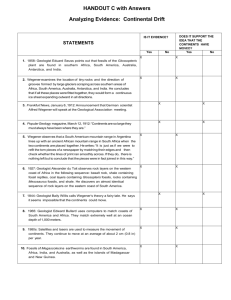

advertisement

IN THE CIRCUIT COURT OF THE EIGHTEENTH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT IN AND FOR COUNTY, FLORIDA CIVIL DIVISION JAMES PLAINTIFFS and NATALIE PLAINTIFFS, Plaintiffs, vs. Case No.: ALPHA INSURANCE COMPANY, Defendant. ______________________________/ DEFENDANT’S MOTION TO EXCLUDE TESTIMONY OF JOHN GEOLOGIST WHICH EXCEEDS THE STANDARDS FOR ADMISSIBILITY UNDER EVIDENCE RULE 90.702 This is an Insurance Coverage dispute regarding an alleged sinkhole loss at Plaintiffs’ residence. Three investigations excluded sinkhole as a cause of loss, including a statutorilycompliant geotechnical investigation as required by Florida Statute 627.7072, a separate peer review of that investigation, and a Neutral Evaluation. The statutory investigation conducted by Geovestigate followed the testing referenced in the Florida sinkhole statute, using recognized and accepted ASTM engineering standards, and the generally accepted standards in the industry, which were developed by Geologists and geotechnical professionals to assure standardized procedures for sinkhole investigations. Plaintiffs, on the other hand, retained a Geologist named John Geologist, who disagrees with these three investigations. While both Geologist and Geovestigate conducted “SPT” subsurface borings, Mr. Geologist re-interpreted the boring results, espousing a theory which is not generally accepted in the field, and which cannot be challenged or tested. His theory, which he calls the “Calculated Overburden Analysis,” has never been used (except by him) in sinkhole testing. The analysis requires Mr. Geologist, who is not an engineer, to engage in engineering calculations, which are beyond the scope of his expertise as a Geologist. Furthermore, Mr. Geologist offered an opinion as to the meaning of legislative terms in the sinkhole statute, which usurps this Court’s role to determine issues of law, and instruct the jury as to the meaning of such terms. Accordingly, Alpha Insurance Company, (“Alpha”) moves to exclude the opinion testimony of Geologist John Geologist, regarding the interpretation of SPT boring N Values based on his “Calculated Overburden Analysis,” opinions which he concedes may only be determined by engineering calculations, along with other opinions which cannot be tested, and opinions with respect to the meaning of legislative enactments, which are legal issues to be determined by the Court. Under the standard for admission of expert testimony outlined in Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 509 U.S. 579 (1993), and adopted in the Florida Rules of Evidence, Mr. Geologist’ testimony should be excluded because: A. Mr. Geologist is not permitted to offer testimony about engineering standards and calculations because he is a Geologist, not a licensed engineer, and therefore, is not qualified to offer engineering opinions; B. Mr. Geologist is not permitted to offer opinions based on an untested methodology, which is not generally accepted, has not been peer reviewed, and which cannot be independently tested and verified; C. Mr. Geologist is not permitted to offer an opinion regarding the meaning of a statutory term because this is a job for the Court; D. Mr. Geologist is not permitted to offer opinions based on mere assumptions, as to which there is no factual evidence, based on his own say-so. Mr. Geologist’ claim to years of experience does not excuse him from Daubert scrutiny. STATEMENT OF FACTS Alpha provided homeowner’s insurance to Plaintiffs under a policy issued on April 22, 2007, which was in effect until April 22, 2012. In May, 2011, Plaintiffs, through a Public Adjuster, provided notice of a claim alleging settlement cracks caused by sinkhole activity. In response, Alpha retained Geovestigate, Inc. to conduct a statutorily-compliant sinkhole investigation pursuant to Florida Statute 627.707. Geovestigate conducted testing in accordance with Florida’s sinkhole investigation requirements, including a review of the lithology and regional conditions, a site investigation to identify surface conditions, an interview with the property owner, hand auger borings to determine the nature of near surface materials, hand cone penetration tests to investigate the bearing capacity of the near surface materials, test pits, Ground Penetrating Radar soundings to determine evidence for the presence of subsurface conditions, Electrical Resistivity Imaging to identify site specific geological conditions, an investigation of the structure, a floor elevation survey to record variations in elevation within the structure, and standard penetration test (or “SPT”) borings to explore deeper subsurface conditions. Based upon the data collected during the investigation, Geovestigate issued a report dated August 17, 2011, signed by both a professional Geologist and a professional engineer. Significantly, none of Geovestigate’ SPT borings encountered a limestone or similar rock formation despite drilling to depths of almost 100 feet, and the measurements from the SPT borings (known as “N values”) did not establish raveling of soils or underground voids. Based on this data, Geovestigate ruled out sinkhole activity as a cause of damage, concluded there was no change in elevation in the structure beyond normal parameters, and identified other causes of settlement which were excluded under the policy. Before making its coverage decision, Alpha requested a peer review of Geovestigate’ investigation from MCD Geosciences and Engineering. MCD’s principal, another licensed professional Geologist, agreed with Geovestigate’ conclusions that sinkhole activity was not a cause of damage. Based on Geovestigate’ conclusions and the peer review, Alpha denied the claim on September 8, 2011. Apparently unhappy with these results, Plaintiffs filed suit for breach of contract. After being served with the lawsuit, Alpha requested Neutral Evaluation, the alternate procedure for resolution of disputed sinkhole insurance claims outlined by Florida Statute 627.7074. According to this procedure, the Department of Financial Services appointed a professional engineer, Theresa Bailey, of KCI Technologies, as the Neutral Evaluator. She conducted her own investigation, including a review of all reports, photographs, test and lab results from both parties, and held a meeting with representatives of both Plaintiffs and Defendant at the property. Afterwards, Ms. Bailey also concluded that sinkhole activity could be eliminated as a cause of the damage to the home. Despite the findings of Geovestigate, MCD, and the Neutral Evaluator, Plaintiffs continued to pursue this lawsuit. In order to be covered by the policy, the insured must sustain a “sinkhole loss” caused by “sinkhole activity.” Both the policy and the statute provide the following definitions: (c) “Sinkhole loss” means structural damage to the building, including the foundation, caused by sinkhole activity… (d) “Sinkhole activity” means settlement or systematic weakening of the earth supporting such property only when such settlement or systematic weakening results from movement or raveling of soils, sediments, or rock materials into subterranean voids created by the effect of water on a limestone or similar rock formation. §§ 627.706 (c) & (d), Fla. Stat; Policy (emphasis added). By its express terms, the definition of “sinkhole activity” is limited to movement of material into subterranean voids in a limestone or similar rock formation. Absent such a formation, there cannot be “sinkhole activity” as defined by the statute. As a preliminary matter, the Court will need to issue a ruling on the legal meaning of “a limestone or similar rock formation” and make a determination whether such condition exists at the property.1 While Geovestigate’ investigation revealed no limestone bedrock until approximately 100’, Plaintiffs’ Geologist N.S. “John” Geologist contends that shell material starting 30’ below the property constitutes limestone material that has undergone dissolution/collapse. Geologist claims that because shell material dissolves similar to limestone, the shell within the unconsolidated mixed soils constitutes a “similar rock formation.” The flaw in Mr. Geologist’ position is that the shell was identified within layers of unconsolidated soils which also include sand and clay, and was not within a “formation” as required by the statute. Mr. Geologist’ interpretation would expand the definition of “similar rock formation” and “sinkhole activity” well beyond the language of the statute, well beyond the intent of the legislature and would include any property in the state which contains any shell material whatsoever in the soil. More significantly, the proposed testimony usurps the Court’s role of interpreting the meaning of a statute and instructing the jury as to that meaning. Mr. Geologist also claims that he confirmed sinkhole activity by applying a theory he calls the “Calculated Overburden Analysis” to the actual SPT boring data. The SPT borings gather data points known as N values which are determined based on the number of blows it takes a 140 pound hammer to drive a sampler through 24 inches of the subsurface. The N value measures the strength 1 Defendant has filed a companion Motion under Florida Rule of Civil Procedure 1.200 (a)(9) and 1.200 (b)(6) with respect to this preliminary issue. Notably, if there is no “sinkhole activity” as defined by statute, based upon the subsurface conditions at the property, Plaintiffs cannot meet the statutory definition of a sinkhole, and a summary disposition may be appropriate. See Roberts v. Braynon, 90 So. 2d 623 (S. Ct. 1956). of the subsurface layer. THE “CALCULATED OVERBURDEN ANALYSIS” According to Geologist’ theory, he “calculates” what the N Values “should be” using an engineering formula, and then compares these calculated N Values to those actually measured at the site. If the N Values actually measured at the site are lower than what his calculations said they should be, he confirms sinkhole activity. While Mr. Geologist did not discuss the Calculated Overburden Analysis in his initial report, (Ex. A.), he testified at his January deposition, (Ex. B), that his conclusions regarding systematic weakening of the soil were based on adjustment of the N-values in the SPT boring data to account for “overburden pressures.” Ex. B, T. 34:10-17. He then compared the actual Nvalues from the SPT boring data to a hypothesis of what he believed the N values “should” be, after making calculations to account for “overburden pressures.” Ex. B, T. 34:10-17. Geologist originally testified that the use of this overburden analysis was based on a paper by “some Russian guy.” Ex. B. T. 34:18-20. According to Geologist, this hypothesis allowed him to offer an opinion as to what an SPT N-value “should” be at any given depth, which when compared to the actual N-value collected by the SPT borings showed that systematic weakening has occurred. Accordingly, Mr. Geologist’ opinion of systematic weakening was not based upon the actual measured N values, as generally accepted and traditionally done in sinkhole investigations, but upon “what he would expect them to be” based upon his “Overburden Theory.” His conclusion at deposition, that sinkhole activity is present, was based on the Overburden Theory, but without having conducted any actual calculations. Ex. B, T. 44:18- 45:1, 71:1-20, 36:22-37:6. In other words, his opinions at that point were based upon his subjective hypothetical theory by “some Russian guy,” and guesses regarding what the actual density “should be” at the site. In his February 28, 2014 report, Mr. Geologist actually conducted the engineering calculations to support his opinion regarding this Overburden Analysis. Ex. C. His findings are set forth in charts which compare the actual SPT N values with what his calculations determine the N values at the property “should” be. Ex. C, Bates No. 01275-01279. On April 14, 2014 Mr. Geologist was questioned about these calculations. He testified that in order to assign an overburden pressure he had to calculate a relative density using a few constants that were developed to create an equation, which “produces an N value that would be comparable or that you would expect to get for that specific relative density.” Ex. D, T. 23:2124:13. Based upon these calculations, and according to Mr. Geologist’ charts, even though a boring records an N value identified as “stiff” or “dense” under generally recognized ASTM standards, if his calculations indicate the N values should be higher, he can confirm systematic weakening, regardless of – and in fact in spite of – the actual field results. When questioned about the source for his calculation, Mr. Geologist first referenced equations in a paper by Cubroniovski & Ishihira. Ex. D, T. 23:2-12. The abstract for this publication describes it as relating to fine John soils and naturally John deposits in Japan. See Aff. J. Smith, ¶6 (Aug. 28, 2014) (attached as Exhibit E.). However, Geologist was as unable to identify the published information he used to determine the relative soil density data: Q. In this case, what chart or information did you use to make the calculations? … A. Couldn’t really tell you. This probably came out of Tergagi and Peck or one of the Chen soil mechanics books. Ex. D, T. 28:17-23. He was similarly unable to identify the source of the “constants” that were factored into the calculation, and could only respond that they were “in geotechnical publications, such as soil mechanics books. I mean that’s where all this comes from.” Ex. D, T. 29:4-10. Accordingly, Mr. Geologist provided at least four different sources from which he developed his calculations, but was not able to identify the formula he actually used, the constants he used, or the source for his input data. Mr. Geologist’ inability to identify the source of his work renders it untestable, uncheckable and inherently unreliable. Similarly, it is clear that Mr. Geologist himself did not use the sources in a reliable manner. Mr. Geologist, not being an engineer, made numerous mistakes in applying the formula, including the use of constants rather than variables, using a formula related to fine sands without regard to the actual consistency and characteristics of the soil at the site, and by failing to include necessary steps in conducting the calculation. The result is the application of an incorrect methodology, which skips a number of required steps. Ex. E, Aff. J. Smith at ¶¶ 8-14. Geologist’ opinion with respect to the Calculated Overburden Analysis falls short of every Daubert test for admissibility – he is not an engineer and thus not qualified to conduct engineering calculations or testify with respect to engineering issues. His Calculated Overburden Analysis also falls short of each Daubert test for reliability – general acceptance, peer review, testability, control standards, and error rate. This Court, exercising its function as “gatekeeper,” under the Daubert standard adopted by the Florida legislature should preclude Mr. Geologist’ testimony related to the “Calculated Overburden Analysis,” engineering opinions, and subjective non measurable interpretations and conclusions. His methods are so dependent on his subjective interpretations that they cannot be tested in a scientific manner. Such proposed testimony wholly fails the standards for admissibility under Rule 702 and Daubert. LEGAL STANDARD In 2013, the Florida legislature amended Florida Statute § 90.702 to adopt the standards for expert testimony in the courts of Florida as set forth in three Supreme Court decisions and implemented under the Federal Rule of Evidence 702 over 20 years ago. The purpose of the Legislation was clear – “subjective belief and unsupported speculation are henceforth inadmissible.” Perez v. Bell South Telecomms., Inc., 138 So. 3d 492, 499 (Fla. 3d DCA Apr. 23, 2014). The standards of admissibility are set forth in Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 509 U.S. 579, 589 (1993), General Electric Co. v. Joiner, 522 U.S. 136 (1997), and Kumho Tire Co. v. Carmichael, 526 U.S. 137 (1999) as well as subsequent case law.2 Expert testimony is admissible only “if (1) the testimony is based upon sufficient facts or data, (2) the testimony is the product of reliable principles and methods, and, (3) the witness has applied the principles and methods reliably to the facts of the case.” §90.702, Fla. Stat. (2013). In Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the Supreme Court explained that trial judges must be gatekeepers with respect to expert testimony and “ensure that any and all scientific testimony or evidence admitted is not only relevant, but reliable.” 509 U.S. 579, 589 (1993). The trial court must make “a preliminary assessment of whether the reasoning or methodology underlying the testimony is scientifically valid and of whether that reasoning or methodology properly can be applied to the facts in issue.” Id. at 592. To be admissible under Daubert, expert testimony must be both reliable and relevant. A court first must ask whether the scientific methodology underlying the testimony is 2 The legislation went into effect on July 1, 2013 reliable—is it “ground[ed] in the methods and procedures of science” and “supported by appropriate validation.” Id. at 590. The Court provided a series of factors that courts may consider in determining whether a methodology is reliable: (1) Testability: “a key question to be answered in determining whether a theory or technique is scientific knowledge that will assist the trier of fact will be whether it can be (and has been) tested”; (2) Peer review: “whether the theory or technique has been subjected to peer review and publication”; (3) Error rate: “the court ordinarily should consider the known or potential rate of error”; (4) Control standards: “the court ordinarily should consider … the existence and maintenance of standards controlling the technique’s operation”; (5) General acceptance: “Widespread acceptance can be an important factor in ruling particular evidence admissible.” Id. at 593-94 (emphasis added). The Advisory Committee on the 2000 amendments to Rule 702 voiced support for the five reliability factors listed in Daubert, and also pointed to five other factors that courts could consider in evaluating the reliability of an expert’s scientific testimony: (6) Independence from the litigation: Whether experts are “proposing to testify about matters growing naturally and directly out of research they have conducted independent of the litigation, or whether they have developed their opinions expressly for purposes of testifying”; (7) Unjustified extrapolation: Whether the expert has unjustifiably extrapolated from an accepted premise to an unfounded conclusion; (8) Alternative explanations: Whether the expert has adequately accounted for obvious alternative explanations; (9) Due care: Whether the expert “is being as careful as he would be in his regular professional work outside his paid litigation consulting”; (10) Reliability of field of expertise: Whether the field of expertise claimed by the expert is known to reach reliable results for the type of opinion the expert would give. Fed. R. Evid. 702 (Notes of Advisory Committee on 2000 amendments and cases cited therein.) The second prong of Daubert is whether the testimony is relevant to the questions at hand. Regardless of the soundness of the methodology, the expert’s opinion must “assist the trier of fact to understand the evidence or to determine a fact in issue.” Daubert, 509 U.S. at 591. The Court described this prong as a question of “fit,” and gave an example of testimony about the phases of the moon: such testimony might be relevant if darkness is an issue in the case, but not if the issue is whether an individual was unusually likely to behave irrationally on a given night. Id. The Supreme Court elaborated on the scope of a trial court’s inquiry into the expert’s underlying methodology in General Electric Co. v. Joiner, 522 U.S. 136 (1997), stressing that the trial court should examine whether there is a valid connection based on existing factual data between the expert’s methodology and the expert’s conclusion: Conclusion and methodology are not entirely distinct from one another. Trained experts commonly extrapolate from existing data. But nothing in either Daubert or the Federal Rules of Evidence requires a district court to admit opinion evidence which is connected to existing data only by the ipse dixit of the expert. Id. at 146 (emphasis added). Judges are free to consider the validity of the conclusions experts draw from otherwise reliable data and can exclude testimony when “there is simply too great an analytical gap between the data and the opinion proffered.” Id. In Kumho Tire Co. v. Carmichael, 526 U.S. 137 (1999), the Supreme Court held that the trial court’s “gatekeeping obligation” applies not only to scientists but to all experts. Id. at 147. The Supreme Court emphasized that the trial court’s role is not to determine whether the expert’s methodology is sound as an abstract or theoretical matter but “to determine reliability in light of the particular facts and circumstances of the particular case.” Id. at 153, 158. The question is whether the expert’s approach is a reliable method “to draw a conclusion regarding the particular matter to which the expert testimony was directly relevant.” Id. at 154 (emphasis in the original). The Eleventh Circuit and the Unites States District Courts in Florida have adopted these standards. See City of Tuscaloosa v. Harcos Chemicals Inc., 158 F. 3d 548 (11th Cir. 1998); Atlanta Gas Light Co. v. UGI Utilities, Inc., 2004 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 30691 (M.D. Fla. Nov. 24, 2004) (“To insure these requirements are met the Eleventh Circuit has devised a three-part test in which expert testimony is admissible if: (1) the expert is qualified to testify competently on the matters on which he intends to address; (2) the methodology by which the expert reaches his conclusions is sufficiently reliable as determined by the sort of inquiry mandated in Daubert; and (3) the testimony assists the trier of fact through the application of scientific, technical or specialized expertise, to understand the evidence or determine a fact in issue.”). The burden of proving qualifications, reliability and relevance rests on the party offering the expert. Daubert, 509 U.S. at 592, n10; Allison v. McGhan Medical Corp. 184 F. 3d 1300, 1306 (11th Cir. 1999). ARGUMENT Mr. Geologist’ expertise, methods, and opinions fail every test for scientific reliability prescribed by the Rules of Evidence and Daubert and its progeny. There are multiple recognized and accepted standards for conducting underground soil investigations, including “SPT” Boring Test Standards, ASTM D1586-11 (Standards for Standard Penetration Tests and Split Barrel Sampling of Soils), and other procedures reviewed and recommended in a state-sponsored document titled Florida Special Publication 57 (Geological and Geotechnical Investigation Procedures for Evaluation of the Causes of Sinkhole Subsidence Damage in Florida). Florida Geologists and Geotechnical Engineers regularly use these standards, guides, and tests, including data collected by SPT borings known as “N” values to determine the density of soils underground in accordance with accepted standards for sinkhole investigations. Mr. Geologist proffers of a completely different, non-accepted, non-peer reviewed “method” to undermine the actual SPT boring results, in order to “substitute” fictional comparison calculations that are being utilized to reach a subjective result-oriented conclusion. A. Geologist is not qualified to testify as an expert on the matters he addresses because he is a Geologist and is attempting to apply engineering calculations. Under Evidence Rule 90.702, a witness must be “qualified as an expert by knowledge, skill, experience, training or education.” An expert must “stay within the reasonable confines of his subject area, and cannot render expert opinion on an entirely different field or discipline.” Lappe v. Am. Honda Motor Co., 857 F. Supp. 222, 227 (N.D. N.Y. 1994), aff’d, 101 F.3d 682 (2d Cir. 1996). In Dura Automotive Systems of Indiana, Inc. v. CTS Corp., 285 F.3d 609, 614 (7th Cir. 2002), the well regarded jurist, Judge Posner, confirmed the exclusion of an expert hydrologist who strayed beyond his field, and warned “the Daubert test must be applied with due regard for the specialization of modern science. A scientist, however well-credentialed he might be, is not permitted to be the mouthpiece of a scientist in a different specialty. That would not be responsible science.” See also Fireman’s Fund Ins. Co. v. Videfreeze Corp., 540 F.2d 1171, 1180 (3d. Cir. 1976) (precluding Geologist from testifying about earthquake damage where Geologist was qualified to testify about rock formation or slippage but had no training in seismology); Mattke v. Deschamps, 374 F.3d 667, 671 (8th Cir. 2004) (physician specializing in sleep and pulmonary disorders was not qualified to offer opinion on aspect of pathology); O’Conner v. Commonwealth Edison Co., 807 F. Supp. 1376 (C.D. Ill. 1992), aff’d, 13 F.3d 1090 (7th Cir. 1994) (ophthalmologist prohibited from testifying in action alleging radiation exposure caused plaintiff’s cataracts because ophthalmologist was not qualified in field of radiationinduced cataracts); Sadler v. Int'l Paper Co., 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 59422, 2014 WL 1682014 (W.D. La. Apr. 28, 2014) (engineer permitted to testify about characteristics of fuel used in plant, and the odor emanating from such fuel, as within the scope of his expertise, but not as to his conclusions of negative health impacts of emissions, or the plants statutory failure to meet social responsibility, which were not within scope of expertise, or which were legal conclusions). As a Geologist, Mr. Geologist may give geological opinions about soil quality, soil classification, and soil content from a Geologist’s perspective, but he should not be allowed to offer opinions regarding engineering standards or to conduct engineering calculations, such as the Calculated Overburden Pressure. Mr. Geologist has previously conceded that he is not competent to make required engineering calculations to determine sinkhole loss, and he should not be permitted to testify to that opinion to the jury. Ex. F, T. 37:14-21, 44:6-13, 113:25-114:5, 124:24-125:3. Yet in this case he has apparently borrowed from several sources in the field of civil engineering, which include multiple formula for developing tolerances for building foundation, and has conducted, from his pick and choose sources, engineering calculations. The entire exercise is outside Mr. Geologist’ sphere of expertise.3 Similarly, Mr. Geologist is not competent to challenge or critique the ASTM standards adopted by Geovestigate in its investigation as he is not an engineer, or to recalculate those findings 3 Engineering fundamentally involves the design, construction and operation of artifacts- buildings, bridges, roads…”man-made modifications of nature. George Bugliarello, The Social Function of “Engineering” 73.86 n. 1 (Hedy Sladovich, ed. 1991). Engineers have special skills that flow from a body of theoretical knowledge, M. David Burghadt, Introduction to the Engineering Profession, 88 (1991). The emphasis of engineering is the analysis and design that is fundamental to engineering. Id. It differs from science, Mr. Geologist expertise, in that engineering focuses on modifying nature, Bugliarello, Engineering and the Crossroads of our Species, 28 The bridge 9, 10 (No. 1 Spring 1998). by using engineering calculations. ASTM standards are engineering standards. See http://www.astm.org/Standards/geotechnical-engineering-standards.html. Mr. Geologist has been specifically warned about practicing engineering while testifying in sinkhole litigation. In November 2011, the Florida Board of Professional Engineers ordered him to “cease the practice of professional engineering, without a license.” Ex. G. His Appeal of that Order was denied on December 30, 2011. Id. In that case he was giving engineering advice in a sinkhole matter concerning the location and method of underpinning of a structure. Id. Mr. Geologist has also previously been precluded from testifying about ASTM soil testing in a sinkhole case in the United States District Court for the Middle District of Florida, when he attempted to critique soil testing conducted by an engineering firm pursuant to ASTM standards. See Ex. H. All of his proposed engineering testimony, including his calculation of overburden pressures, is totally beyond his area of expertise and must be excluded.4 B. Geologist’ methodology, called the “Calculated Overburden Analysis,” fails every test for reliability outlined by Daubert. 1. General Acceptance in the Field of Inquiry The object of the Daubert inquiry is to ensure that a scientist who testifies in court adheres to the same standards of “intellectual rigor” that are demanded in the practice of an expert in the relevant field. Kumho, 526 U.S. at 155-56; Rosen v. Ciba-Geigy Corp., 78 F.3d 316, 318 (7th Cir. 1996). Thus, an expert witness must use the same methodology normally utilized in that expert’s field. If the expert fails to do so, the resulting opinion testimony should be excluded. See McClain v. Metabolife Int'l, Inc., 401 F.3d 1233, 1251 (11th Cir. 2008) (error 4 Obviously, one reason not to allow an expert in one field to wander into another is to assure that the testimony provided to the jury is reliable. The reliability factor is heightened when unqualified experts, are permitted to testify as to a subject which is not within their expertise. This is readily apparent in this case, given Mr. Geologist’ incorrect and incomplete use of the civil engineering formulas. See Ex. E, Aff. Smith at ¶¶ 7-14. While Mr. Geologist can be excused for miss-applying the formula and making several errors, as he is not an engineer, his mistakes underscore why as a Geologist, he is not competent to provide testimony based upon engineering calculations. to permit expert to opine on the toxicity of ingredients in Metabolife where the expert “failed to show the trial court either that his opinions were based upon reliable sources and data or that his methodology comported … with those standards otherwise utilized by experts in the field of toxicology”); Rink v. Cheminova, 400 F.3d 1286, 1290, 1292 (11th Cir. 2005) (district court properly excluded expert retained “to reconstruct the temperatures” at chemical storage sites in different states where the expert’s methods of extrapolating weather data produced calculations that were not scientifically reliable, not tested, and not generally accepted). Furthermore, “the facts on which the expert relies must be reasonably relied on by other experts in the field.” Allen v. Penn. Eng'g Corp., 102 F.3d 194, 198, 199 (5th Cir. 1996) (excluding epidemiological opinion where experts failed to rely on the facts necessary to form epidemiological opinions). In In re TMI Litigation, 193 F.3d 613, 668-669 (3d Cir. 1999), a meteorologist who purported to explain the effect of wind and weather on the disbursement of radioactive particles following the accident at Three Mile Island should not have been permitted to testify under Daubert because he “discarded standard and generally accepted computer models, especially the Gaussian plume model,” in favor of his own numerical models without providing “any testimony, documentation or any other evidence that the numerical models he did use are generally accepted within the meteorological or the broader scientific community.” Geotechnical professionals in the field of sinkhole investigation have developed multiple accepted methodologies for investigating sinkholes. In 2005, the Sinkhole Summit II published Special Publication 57 (Geological and Geotechnical Investigation Procedures for Evaluation of the Causes of Sinkhole Subsidence Damage in Florida). Ex. I. The Publication identifies itself as developing standards for sinkhole investigation by professionals: These various technologies, however, must be utilized in a competent manner along with routine professional care in making reasonable interpretations. There can be a generalized listing of the steps, processes and tools a competent professional would utilize or consider in carrying out such an investigation. These “protocols” are included later in this report. Ex. I. at p. 3. Publication 57 emphasized that Sinkhole Investigations should be conducted in an unbiased, scientifically credible, and professional manner: It is important that all consultants or other professionals who perform this service produce thorough, unbiased, scientifically credible, evaluations as to the cause(s) of the damage that has resulted in a sinkhole claim. These guidelines are intended to ensure that the procedures followed by any geological consultants investigating sinkhole claims in Florida are thorough and consistent. The protocols are intended to ensure that sufficient information is gathered to assist in sinkhole claim evaluation and standard methods that can withstand the evidentiary competence tests required for admission in state and federal court. Ex. I, pp 4-5. (emphasis added). Similarly ASTM D1586- 1, (American Standards for Testing and Measurement) sets forth Standard Test Measurements for Standard Penetration Test (SPT) and Split –Barrel Sampling of Soils. ASTM states “this test method is used extensively in a great variety of geotechnical exploration projects.” Instead of relying on time-honored methods and procedures, Geologist bases his conclusions of “raveling and sinkhole activity” on his “calculated overburden analysis.” Ex. B, T. 35:25-37, 6, 71:1-20, 75:14-19. According to Geologist’ own testimony, however, the analysis was developed to account for building design tolerances, Ex. F, T. 30:3-14; the theory was not developed in relation to sinkhole investigations, Ex. F. T. 31:4-7; and it relates to the need to account for overburden pressure “when you build a foundation.” Ex. F, T. 33:5-18. The sources for the theory referenced by Mr. Geologist all relate to civil engineering, not sinkhole investigation. See Ex. E, J. Also, Mr. Geologist could not identify anyone else who has used this theory in the context of sinkhole investigations. Ex. F. T. 33:25-34:12. Further, Mr. Geologist admitted that the geotechnical statute in Florida does not recognize the “theory.” Ex. B. T. 35:8-10. In his Affidavit, Richard Professor, a licensed professional Geologist, Professor Emeritus and Past Chair of the University of Florida Geology Department, who was involved with the development of Florida sinkhole investigation procedures, states that “the ‘Calculated Overburden Analysis’ that Geologist describes is not a valid geological methodology to determine the existence or non-existence of sinkhole activity, nor is it a theory that has attained general (or any) acceptance in the geological community.” Aff. A. Professor ¶¶ 9-13 (September 3, 2014) (attached as Exhibit J). Further, Dr. Professor states that in his experience, “neither [Geologist’] analysis, nor any semblance of it, has ever been used in the field by any Geologist.” Id. at ¶11. Geologist’ eschews the generally accepted standards and has opted instead to rely on the design theory developed by “some Russian guy” to “correct” the SPT N values. Rather than using the actual on site N Values, his theory ignores the actual data by substituting a theoretical measure for the actual findings at the site. There is no question that the method is not generally accepted or even appropriate in this field. See Ex. E. Aff. J. Smith; ¶¶ 18-20; Ex. J. Aff. A. Professor, ¶¶ 8-13. 2. Peer Review There is no evidence that Geologist’ methodology has been peer reviewed for use in sinkhole investigations. Peer review, the “submission to the scrutiny of the scientific community,” as Daubert instructs, “is a component of ‘good science,’ in part because it increases the likelihood that substantive flaws in methodology will be detected.” Daubert, 509 U.S. at 593-94. Peer review is the process of subjecting an author’s scholarly work, research, or ideas to the scrutiny of others who are experts in the same field. Courts recognize that peer review is a hallmark of scientific reliability. See Wheat v. Pfizer, Inc., 31 F.3d 340, 343 (5th Cir. 1994) (affirming exclusion of physician’s theory of drug interactions because the theory had not been studied and “[n]either had it been subjected to peer review and publication, which Daubert also identifies as key”); Stanczyk v. Black & Decker, Inc., 836 F. Supp. 565, 567 (N.D. Ill. 1993) (excluding mechanical engineer’s testimony because he offered no testable design to support his techniques, which had never been submitted for peer review and publication). If experts’ methods have not been subjected to peer review, then “the experts must explain precisely how they went about reaching their conclusions and point to some objective source—a learned treatise, the policy statement of a professional association, a published article in a reputable scientific journal or the like—to show that he has followed the scientific method, as it is practiced by (at least) a recognized minority of scientists in his field.” Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 43 F.3d 1311, 1318-19 (9th Cir. 1995) (on remand from the landmark Daubert decision) (citing United States v. Rincon, 28 F.3d 921, 924 (9th Cir. 1994), cert. denied, 516 U.S. 869 (1995)). Mr. Geologist admits that the Calculated Overburden Analysis has not been recognized for geotechnical investigations in Florida. It has never been subjected to peer review with respect to its use in determining the existence of sinkhole activity. Ex. J, Aff. A. Professor at ¶¶ 12-13. It has not been tested, subjected to experimentation or verification, there is no known error rate, and no known validation of the theory with respect to sinkhole investigations. Id. at ¶12; Ex. E, Aff. J. Smith at ¶¶ 18-19. Significantly, Mr. Geologist’ amalgam of formulas and calculations from multiple sources, which was developed for litigation, is unique and could not possibly be peer reviewed. It is an attempt to cobble together a calculation from a general theory, which fails to follow the formula and steps which are required. It is unique unto itself. Ex. E. Aff. J. Smith at ¶¶ 7-14. 3. Reliability, Testability, Error Rate, Control Standards On April 14, 2014, Mr. Geologist was questioned at length about the source of data he used for his calculations, the factors he included, and the formulas he applied. As outlined above, Geologist testified that he used relative density and a few constants to create an equation that produces an expected N value. However, Geologist was only able to identify a general source for the data; he was not able to identify the published information he used for the soil density, the source of the “constants” that factored into the equation, or the source of the equation itself. Ex. D, T. 23:21-24:13, 23:2-12, 28:17-23, 29:4-10. Geologist’ inability to identify the source of his work renders it untestable, uncheckable and inherently unreliable. Rink v. Cheminova, 400 F.3d 1286, 1290, 1292 (11th Cir. 2005) (district court properly excluded expert retained “to reconstruct the temperatures” at chemical storage sites in different states where the expert’s methods of extrapolating weather data produced calculations that were not scientifically reliable, not tested, and not generally accepted). Further, Mr. Geologist did not apply the sources in a reliable manner because he made a number of errors in the calculation: he used an improper number of variables (two instead of three), an improper number of constants (four instead of three), inserted constants in the formula which should have been variables, (used a constant relative density of 100%, which should have been 20-90% based upon particle size, amount of silt and clay, and grain size and shape), did not apply proper density and weight factors, and failed to consider horizontal stresses. Ex. E, Aff. J. Smith at ¶¶ 7-14. His results are unscientific, incomplete and unreliable. Id. The bottom line is that the calculations were just wrong, as was his testimony about them. And his work cannot be tested or checked. Therefore it is unreliable and inadmissible. In B.H. v. Gold Fields Mining Corporation, 2007 U.S. Dist. Lexis 4612 (N.D. Ok. Jan. 22, 2007), the defendants successfully challenged plaintiff’s expert who had modified calculated factors, (such as Geologist has done here with the N values), in reaching his conclusions. The defendants argued that the C factor used by the expert was 100 times more than what was appropriate and that the expert deviated from accepted applications of the model. Id. at *3-11. Like here, the plaintiff’s expert acknowledged that he deviated from the normal application of the C value; however, he claimed that this deviation was necessary to determine the windblown emissions on a local scale instead of a regional scale. Id. The court rejected the plaintiff’s argument and found the expert’s opinion to be unreliable. The court noted that the expert (like Mr. Geologist does here) developed his own mathematical values for data and had no support in his report or in the peer-reviewed literature for use of his C factor. Id. at 12-13. The court emphasized that the issue of admissibility must focus not on the conclusions but on the methodology employed, in reaching the conclusions and that analytical gaps in an expert’s methodology can be a sufficient basis to exclude expert testimony. The court observed that “any step that renders the analysis unreliable…renders the expert testimony inadmissible. This is true whether the step completely changes a reliable methodology or merely misapplies that methodology.” Id. at 11. Mr. Geologist missed several steps in his analysis, and substituted constants for variables in conducting his calculation. Ex. E. Aff. J. Smith at ¶¶7-8 (a)-(d). Each missed step renders the testimony unreliable. In B&H, the court also found that the testing was an “after the fact” justification to create the results Plaintiff desired (supra, at *12) and concluded that it “would not be fulfilling its duty as gatekeeper if it permitted the introduction of novel scientific methodology based solely on the assurances of the expert himself.” B & H, supra. at *13. See also Cartwright v. Home Depot U.S.A., 936 F. Supp. 900, (M.D. Fla. Jul. 23, 1996) (Expert testimony should be excluded where expert cannot explain methodology or where witness merely providing personal hypothesis: “only a hypothesis which he had yet to attempt to verify or disprove by subjecting it to the rigors of scientific testing”). Mr. Geologist developed his own (unscientific) formula, and his own (unscientific) values, in a second report to self justify his prior hypothesis. Each step in his methodology is simply wrong, and accordingly, it is not sufficiently reliable to permit it to be presented to the trier of fact. Mr. Geologist’ Calculated Overburden Analysis calculations is sui generis (of its own kind), was created solely for litigation, and has not been tested, subject to experimentation, or verification, there is no known error rate, and no known validation of the theory with respect to sinkhole investigations. Ex. E. J. Smith; ¶¶ 12-13; Ex. J. Aff. A. Professor ¶¶ 11-13. C. Geologist’ testimony regarding the definition of “similar rock formation” must be excluded because the meaning of the term is a legal issue for the Court to decide. In order to recover under the policy, the Plaintiffs’ insured home must have sustained a “sinkhole loss” caused by “sinkhole activity.” As outlined above, the policy and statutory definitions for these terms address settlement, but “only when such settlement … results from movement or raveling of soils … into subterranean voids … [in] a limestone or similar rock formation.” §§ 627.706 (c) & (d), Fla. Stat., Policy. By definition, absent “a limestone or similar rock formation” there cannot be “sinkhole activity.” Accordingly, a preliminary showing that subterranean voids created by the action of water on limestone or a similar rock formation is required. See, Cincinnati Ins. Co. v. Wiltshire, 472 So. 2d 1276 (Fla. 1st DCA 1985) (reversing trial court finding of sinkhole activity, where expert opined holes under driveway were caused by the displacement of sand that could contain calcium carbonate, silicate, and iron which would dissolve in water because the cause of the holes was displacement of sand and not settlement resulting from “subterranean voids created by the action of water on limestone or similar rock formations”). The SPT borings completed by Geovestigate and Geologist did not reach limestone bedrock until approximately 94 feet below the surface. The absence of limestone bedrock until this depth was a factor in Geovestigate’ conclusion that there was no “sinkhole activity.” Mr. Geologist proffers the opinion that because the shell material (shell marl) within the soils above the limestone bedrock dissolves similar to limestone, the shell composition within the overlaying mixed soils constituted a “similar rock formation.” In his December 2011 report he identifies shell within the upper soil layers as “carbonate shell marl” which he claims “constitutes limestone material.” Ex. A at p. 1. Mr. Geologist’ opinion as to the composition of the soil in the borings is well within his realm of expertise. However, in his depositions, he goes beyond this expert opinion, and offers testimony about the meaning of the sinkhole statute, asserting that the “shell marl” within the John upper deposits constitutes “a limestone or similar rock foundation” under the statute. It is not Mr. Geologist’ job to interpret or instruct the jury with respect to the meaning or applicability of the statute. See, Companion motion In Limine. Yet that is exactly what his opinion purports to do. He testified that as long as any layer of soil contains a minimal amount of carbonate material, it qualifies as a “similar rock formation” under the Florida sinkhole statute. Ex. B, T. 23:21-24:24. In fact, under Mr. Geologist’ interpretation, a layer of sand with “one shell” would qualify as “a limestone or similar rock formation.” Ex. B, T. 25:21-26:10 (as long as there is calcium carbonate present, it constitutes a similar rock formation). Notably, this exact theory was rejected by the First District in Cincinnati v. Wilshire, when the court reversed a trial court’s finding of sinkhole damage because shifting sand with material that is subject to dissolution did not meet the definition of sinkhole. Despite the merit – or lack thereof – in Mr. Geologist’ position, it is the Court’s role to instruct the trier of fact on the meaning of the statute, including the meaning of the term “a limestone or similar rock formation.” Osborne v. Dumoulin, 55 So. 3d 577, 581 (Fla. 2011) (“The determination of the meaning of a statute is a question of law and thus is subject to de novo review”). Florida courts have held that expert testimony is inadmissible concerning the construction of a statute. See Lee County v. Barnett Banks, Inc., 711 So. 2d 34, (Fla. 2d DCA 1997) (“Expert testimony is not admissible concerning a question of law. Statutory construction is a legal determination to be made by the trial judge, with the assistance of counsels’ legal arguments, not by way of ‘expert opinion.’”); Devin v. City of Hollywood, 351 So. 2d 1022, 1026 (Fla. 4th DCA 1976); Hann v. Balogh, 920 So. 2d 1250 (Fla. 2d DCA 2006); see also Gyongyosi v. Miller, 80 So. 3d 1070, (Fla. 4th DCA 2012) ; Edward J. Seibert, A.I.A., Architect & Planner, P.A. v. Bayport Beach & Tennis Club Ass'n, 573 So. 2d 889, 891-92 (Fla. 2d DCA 1990). See Discussion of Cases, in Companion Motion In Limine, at pp. 4-6. The Court may permit Mr. Geologist to testify regarding the composition of the soils, the characteristic of the soils, the percentage of certain chemicals in the soils, the chemical properties of those materials, and whether he considers limestone and shell to be similar. See Noa v. United Gas Pipeline Co., 305 So. 2d 182, (Fla. 1974). However, he should not be permitted to testify as to the meaning of the statutory term “a limestone or similar rock formation,” or whether the layers above the limestone bedrock constitute “a limestone or similar rock formation” to the jury. That meaning must be determined by the Court and the Court must instruct the jury as to the meaning. D. Geologist’ opinions that the soils contained “micro voids,” which cannot be discerned or measured, should be excluded as they are wholly subjective and incapable of being tested. The “key inquiry” under Daubert is whether a scientific theory or technique “can be (and has been) tested.” 509 U.S. at 593. As Judge Easterbrook explains, an “expert must offer good reason to think that his approach produces an accurate estimate using professional methods, and this estimate must be testable. Someone else using the same data and methods must be able to replicate the result.” Zenith Electronics Corp. v. WH-TV Broadcasting Corp., 395 F.3d 416, 419 (7th Cir. 2005) (emphasis added). An expert’s extrapolations from the raw data behind the expert’s opinions to his or her conclusions must be sound, and any opinions connected to existing data only by the ipse dixit of the expert (the “say-so” of the expert) are not to be admitted. See General Electric Co. v. Joiner, 522 U.S. 136, 146 (1997). Here, Mr. Geologist makes several assumptions and offers several opinions which amount to prohibited “ipse dixit.” His opinions are not based upon what has been tested or seen, but are in fact, contrary to what has been tested or seen. For example, Mr. Geologist testified that while the SPT borings did not show voids (which could be evidence indicative of sinkhole activity), there were “micro voids” present in the SPT borings, even though they could not be measured or seen. Ex. B, T. 24:25-25:15. “Your voids are microscopic, okay.” Ex. B, T. 29:410. These microscopic voids form another basis for his conclusion that there is “sinkhole activity” at the property. However, mere speculation or conjecture is not admissible as a basis for an opinion. In re Air Crash Disaster at New Orleans, La., 795 F.2d 1230 (5th Cir. 1986); Eastern Auto Distributors, Inc. v. Peugeot Motors of America, 795 F.2d 329 (4th Cir. 1986). Courts condemn such “guesswork” which does not satisfy the dictates of Daubert. Sanner v. Bd. of Trade of Chicago, 2001 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 15458, *20-21 (N.D. Ill. Sept. 27, 2001) (precluding testimony because the expert’s method of merely “visually inspecting certain charts and graphs” without testing his conclusions did “not lend itself to verification by the scientific method”); see also Johnson-Lee v. City of Minneapolis, 2004 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 19708, *52 (D. Minn. Sept. 30, 2004) (precluding demographer’s testimony because “[t]he bulk of plaintiffs’ expert’s opinion appears to be based on little more than ‘eyeballing’ the numbers and maps”). Mr. Geologist concedes that most of his opinions are interpretative, meaning they cannot be tested. The “fundamental problem” with this “is that anyone can look at the same map and come up with a different opinion.” See Henry v. St. Croix Alumnia, LLC, 2009 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 31352, *16-17 (D. V.I. Apr. 13, 2009) (rejecting an expert’s “qualitative view” of soil analysis based only on his observations and experience and not on reliable methodologies for that field, such as sample analysis). An expert’s “conclusions that are not falsifiable aren’t worth much to either science or the judiciary.” Zenith, 395 F.3d at 419. Accordingly, Mr. Geologist’ testimony regarding “micro voids” does not meet the standard required by Daubert, and must be excluded as unreliable and untestable. E. Geologist’ Extensive Experience Does Not Excuse His Opinions From Daubert Scrutiny. Mr. Geologist relies heavily on his experience in reaching many of his untested and untestable conclusions. See, e.g., Ex. B. T. 35:6-8, 63:19-20. It is very difficult to effectively cross-examine that type of testimony making Daubert scrutiny even more important: A great deal of expert testimony in American courts is based solely on an expert’s experience and training, which this Article refers to as connoisseur testimony. The most significant feature of connoisseur testimony is that it has no objective basis, and, given selection bias, its underlying reliability in any given case is therefore completely opaque. Unless a connoisseur is intentionally lying, cross-examination is unlikely to reveal any flaws in the expert’s testimony. Expert Witness, Adversarial Bias and the (Partial) Failure of the Daubert Revolution, David E. Bernstein, 93 Iowa Law Review, 2008. The language of Rule 702 and the Advisory Committee Comments make clear that an expert who relies on experience, still must base his testimony “on sufficient facts or data” and that the testimony is the product of reliable principles and methods and that the expert apply the principles and methods reliably to the facts of the case.” In other words, “years of experience” do not let Mr. Geologist off the hook. In fact, the Advisory Committee note to Rule 702 requires that a witness who is “relying solely or primarily on experience … must explain how the experience leads to the conclusion reached, why that experience is a sufficient basis for the opinion, and how the experience is reliably applied to the facts.” The note also warns: “The more subjective and controversial the expert’s inquiry, the more likely the testimony should be excluded as unreliable.” Here, Mr. Geologist has testified that he only works for homeowners, and that each time he has testified, he concluded that there is a sinkhole. Ex. B. T. 7:12-18. Accordingly, his testimony is subject to strict scrutiny. This includes the determination of whether the testimony relies on “sufficient facts or data” and a determination of whether his calculations were conducted to self justify previous hypothesis. B.H. v. Gold Fields Mining Corporation, supra, at 12. The Calculated Overburden testimony does not meet the Rule 702 requirement that an expert rely on “sufficient facts or data” and “apply the principles and methods reliably to the facts of the case.” Therefore, it must be excluded. CONCLUSION For all the foregoing reasons, Alpha’s motion should be granted and Mr. Geologist should not be allowed to testify to the “Calculated Overburden Analysis,” “micro voids,” or his interpretation of the statutory definition of “a limestone or similar rock formation.” CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE I HEREBY CERTIFY that a true and correct copy of the foregoing has been furnished via e-mail to: firm@danahyandmurray.com, David C. Murray, Esquire, Danahy & Murray, PA, 901 W. Swann Avenue, Tampa, FL 33606, Attorney for Plaintiffs, on this day of September, 2014. ____________________________________ MICHAEL K. KIERNAN, ESQUIRE Fla. Bar No. 391964 C. RYAN JONES, ESQUIRE Fla. Bar No. 0029043 REBECCA LEVY-SACHS Fla. Bar. No. 596124 Traub Lieberman Straus & Shrewsberry, LLP Post Office Box 3942 St. Petersburg, Florida 33731 727.898.8100 - Telephone 727.895.4838 - Facsimile Attorneys for Defendant jdenson@traublieberman.com FLPleadings@traublieberman.com