To what extent did the reparations clause of the

advertisement

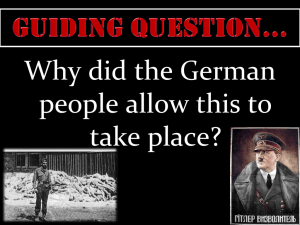

Post-WWI German Economy and Politics (To what extent did the reparations clause of the Treaty of Versailles shape German politics in the post-WWI era?) Word Count: 1883 1 Table of Contents Plan of Investigation 2 Summary of Evidence 2 Evaluation of Sources 5 Analysis 6 Conclusion 8 Bibliography 10 Appendices 12 2 Plan of Investigation This investigation will explore the question “To what extent did the reparations clause of the Treaty of Versailles shape German politics in the post-WWI era?” This paper will first examine the immediate effects, especially the economic and social effects, of the reparations on Germany by examining secondary sources—mainly historians’ and economists’ accounts of the era in Germany—found both online and in libraries. Next the focus of the investigation will switch to examining the relationship between these immediate ramifications of the treaty and the political changes in Germany. More books and articles written by historians will be examined to establish exactly what these political changes were and how they manifested themselves. Primary sources like photographs of German protests and Nazi propaganda from the era as well as historians’ arguments as to the cause of these changes in German politics will be used to investigate the relationship between the reparations and these changes. Ultimately the goal of the research portion is to establish via primary and secondary sources the economic and political changes in Germany following WWI and through historical evidence in primary sources and historical arguments through secondary sources, examine the relationship between these parallel changes. Summary of Evidence The first photograph, from the 1920’s, depicts the scene of a protest in Germany over the terms of the Treaty of Versailles; hundreds and possibly thousands of people have taken to the street over the peace terms.1 In the sixth chapter of the second volume of Mein Kampf, Hitler wrote about, among other things, the efforts he made to convince the German public—many of whom did not see the treaty as entirely unjustified due to the similar treaty Germany had 1 Unknown. Versailles Protest. Photograph. London: Mary Evans Picture Library/Weimar Archive, 2013. Unattributed source. http://www.maryevans.com/images/10/06/30/10063062a.jpg (accessed November 8, 2013). See Appendix A. 3 imposed upon Russia during WWI—that the Treaty of Versailles had been a “scandal and a disgrace… a robbery against [German] people.” He planned on growing to “dominate” public opinions by opposing the treaty; when the public came to realize how unjustified it had been, he expected that they would “give [the NSDAP] their confidence.”2 The next photograph shows a Nazi-lead protest in Germany in 1933. There are thousands of people in the streets to protest, bearing signs that read in German “Day of Versailles, Day of Dishonor!”3 Years later, William Shirer describes in his book the reasons that the peace terms so offended the German people: the worst of these reasons were the disarmament and the territorial concessions, both of which “hurt” and “infuriated” the German people. According to Shirer, the signing of the peace was the day “Germany became a house divided,” leading to the Beer Hall Putsch and the NSDAP’s eventual growing in popularity.4 The Treaty of Versailles itself specifically outlines the terms imposed on Germany: significantly, its military’s reduction to “100,000 men,” its territorial losses to France and Poland, its accepting of “the responsibility” for WWI itself, and its undertaking of providing “compensation” to the Allied Powers.5 In an article published in 1921, Amos Hershey describes Germany’s failure to fully comply with the terms of the treaty and argues that these new protocols enforced upon Germany, namely the requirement that Germany pay “2,000,000,000 gold marks” as well as “26 percent of the value of her exports” annually, exceed Germany’s economic ability to pay. Hershey also recounts the history of the debate of the reparations 2 Hitler, Adolf. Mein Kampf. Translated by James Murphy. Camarillo, CA: Elite Minds, 2009, Volume II Chapter VI. 3 Unknown. Germany 1933. Photograph. London: Mary Evans Picture Library/Weimar Archive, 2013. Unattributed source. http://www.maryevans.com/images/10/06/26/10062676a.jpg (accessed November 8, 2013). See Appendix B. 4 Shirer, William L. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany. New York City: Simon & Schuster, 1960, p53-59, 63-69. 5 US Department of State. The Treaty of Versailles and After: Annotations of the Text of the Treaty. Washington, DC.: Government Printing Office, 1944. Modern History Sourcebook. http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/1919versailles.html, Articles 49, 51, 159, 160, 231, and 232. 4 payments and the consequent meetings between the Allies and Germany.6 Years later, the Italian professor Costantino Bresciani-Turroni wrote on the subject of just how these reparations payments affected the German economy and were the “principle cause” of the crisis involving the value of German mark, cost of living, wholesale good prices, currency circulation, and prices of both imports and exports, as well as the fluctuations in the wages of the working class, their subsequent unionization, and the skyrocketing unemployment rates.7 In the intro to BrescianiTurroni’s book, Lionel Robbins, another economist, noted that the economic conditions described were the “breeding ground” for disaster as well as the father of Hitler’s rise to power.8 Charles Dyar, in an article written in 1922, described the increased political activity of German students and young people: faced with economic struggles and unemployment, more young Germans were aligning themselves with political parties and creating small “selfgoverning bodies” to express their outrage at the unfairness of their conditions.9 Created and circulated beginning in 1924, the Nazi propagandizing poster primarily features a Nazi saying “first bread, then reparations” and pointing at a sad-looking woman with a call to join the NSDAP at the bottom.10 Years later, economist and political scientist Adam Fergusson argues that the economic crisis in Germany “made Hitler possible.” Furthermore, he asserts that the 6 Hershey, Amos S. "German Reparations." The American Journal of International Law 15, no. 3 (July 1921): 41118. Jstor. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2188001, p 412-413, 415-417. 7 Bresciani-Turroni, Costantino. The Economics of Inflation: A Study of Currency Depreciation in Post-War Germany. Translated by Millicent E. Sayers. London: George Allan & Unwin, 1937, p 26-41, 93-99, and 300-312. 8 Robbins, Lionel. Foreword to The Economics of Inflation: A Study of Currency Depreciation in Post-War Germany by Costantino Bresciani-Turroni. Translated by Millicent E. Sayers. London: George Allan & Unwin, 1937, p 5-6. 9 Dyar, Charles B. "The Youth of Germany." The North American Review 215, no. 799 (June 1922): 739-50. Jstor. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25121056, p 741-746. 10 Unknown. Untitled. Cartoon/Poster. Berlin: The Nazi Party, 1924. From the Mary Evans Picture Library/Weimar Archive reproduction of a Nazi poster. http://www.maryevans.com/images/10/06/90/10069088a.jpg (accessed November 8, 2013). See Appendix C. 5 inflation that plagued Germany was worsened by the pressure to make reparations payments, but that the problem of inflation existed independently of reparations and the treaty.11 Evaluation of Sources When Money Dies: the Nightmare of Deficit Spending, Devaluation, and Hyperinflation in Weimar Germany by Adam Fergusson, originally published in 1975, is a book whose purpose is to examine and analyze the economic situation in post-war Germany as well as the concurrent societal changes. In it, Fergusson argues that the roots of the collapse of the German economy can be traced prior to the imposition of the reparation payments, but that these payments did augment the economic problem. Its value lies partially in the author’s reliability: Fergusson was a political and economic journalist before becoming a business consultant and Special Advisor to the European Union. His understanding of politics and the economy and his expertise in such subjects makes his writing and analysis more reliable. Additionally, his book does note social changes and economic changes, rather than just one or the other, and it connects the two more clearly than other sources, which is particularly relevant to this investigation. Although it does analyze social changes, the source is limited in that it does not analyze the accompanying political changes. Political changes can be inferred, but they are not directly or thoroughly addressed. The next source is reproduced Nazi propaganda, a poster showing a Nazi standing up for a downtrodden German woman and choosing her over a fat man—the Allied powers—who is demanding reparations. “First bread, then reparations!” is written across the top in German, and along the bottom is a call for the German people to stand behind and support the NDSAP. Its purpose is to persuade the German people to join and support the Nazi Party, who, according to 11 Fergusson, Adam. When Money Dies: The Nightmare of Deficit Spending, Devaluation, and Hyperinflation in Weimar Germany. New York City: Public Affairs, 2010. 6 the poster, will protect the German people from reparations and economic turmoil. It intends to make a statement and portray the NSDAP as looking out for the German people and acting in their best interests. It is valuable as a source because it shows that the Nazi Party used the economic distress—the sad-looking woman—caused by the reparations to gain influence over the German population and to grow their own popularity. This source directly ties the reparations and the German economy with German politics, and, as a poster created by the official Nazi Party in 1924 (during the time period when the Nazis were beginning to gain influence), it is incredibly relevant to an analysis of the economy’s effects on politics. It is at the same time limited: its creation shows the Nazi perspective but not that of the German people and its effectiveness as propaganda is unable to be determined. Being published in 1924 (before the Nazi Party had taken over control of Germany) means that this poster may not have been distributed widely enough to have had any significant impact on politics at all. Analysis The reparations clause of the Treaty of Versailles first and foremost impacted the German economy in such a way that the economy itself collapsed. By forcing Germany to pay such a significant sum and such a large portion of their economy, the reparations clause overextended the German economy and lead to the period of economic instability and hyperinflation in the early 1920’s.12 However, the economic disaster was not only caused by the reparations—it had begun before the payments were enforced and continued through breaks in required payments13—and thus the reparations cannot be entirely blamed for the hyperinflation and other 12 Bresciani-Turroni, Costantino. The Economics of Inflation: A Study of Currency Depreciation in Post-War Germany. Translated by Millicent E. Sayers. London: George Allan & Unwin, 1937, p 26-41, 93-99, and 300-312. 13 Bresciani-Turroni, Costantino. The Economics of Inflation: A Study of Currency Depreciation in Post-War Germany. Translated by Millicent E. Sayers. London: George Allan & Unwin, 1937, p 26-41, 93-99, and 300-312. 7 problems, despite the importance of their role in how these issues played out.14 In this way, the economic crisis was a wider problem rather than one caused immediately by the ending of WWI and the treaty imposed upon Germany. Regardless of its principle cause, the German economy in turn influenced the political climate. The economic collapse lead to the increasing number of politically active young—and often unemployed or underpaid—people in Germany, who hurried to align themselves with the growing number of viable political parties.15 The newly created Nazi Party began to target and use both the increasing interest in politics and the resentment of the unemployed and underpaid workers to further their own cause. By targeting the economic problems with propaganda, the Nazi Party continued to gain influence over both the German public and eventually German politics.16 The economic distress directly enabled the growth of the Nazi’s popularity17 and Hitler as well as the rest of the Nazis, purposefully capitalized upon the economic distress in order to sway more Germans to their cause.18 A country with an unsteady economy and resentful population was one that was particularly susceptible to leadership that promises a way out of hard times, and thus the German economy made it easier for Hitler and the Nazis to seize control of Weimar Germany. 14 Fergusson, Adam. When Money Dies: The Nightmare of Deficit Spending, Devaluation, and Hyperinflation in Weimar Germany. New York City: Public Affairs, 2010. 15 Hershey, Amos S. "German Reparations." The American Journal of International Law 15, no. 3 (July 1921): 41118. Jstor. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2188001, p 412-413, 415-417. 16 Unknown. Untitled. Cartoon/Poster. Berlin: The Nazi Party, 1924. From the Mary Evans Picture Library/Weimar Archive reproduction of a Nazi poster. http://www.maryevans.com/images/10/06/90/10069088a.jpg (accessed November 8, 2013). See Appendix C. 17 Robbins, Lionel. Foreword to The Economics of Inflation: A Study of Currency Depreciation in Post-War Germany by Costantino Bresciani-Turroni. Translated by Millicent E. Sayers. London: George Allan & Unwin, 1937, p 5-6. 18 Hitler, Adolf. Mein Kampf. Translated by James Murphy. Camarillo, CA: Elite Minds, 2009, Volume II Chapter VI. 8 The treaty as a whole angered the German people and made them desperate for a leader to rebuild their nation’s strength.19 The Germans people protested the treaty in its entirety; the territorial losses and humiliation of the disarmament were particularly egregious and built resentment among Germans towards other Western powers.20 The Nazi Party targeted the immense resentment the Germans had towards the Allied Powers for the treaty: the treaty was a “day of dishonor” to the German people and the Nazis used this in order to encourage people to join their political movement.21 The sense of humiliation at losing territory and their right to a full military bred resentment and a powerful desire to return to the glory of an older Germany, which Hitler promised them. The racial elements of Nazi ideology also appealed to the German public: in particular the Nazi view of the Polish, who were commonly considered an “inferior” people22 and who were specifically referenced in Hitler’s racist plans for his vision of Germany.23 From these sources, it becomes clear that the Nazis, in playing off the gripes of the German people, had plenty of material to work with. Conclusion Despite the huge influence of the reparations clause of the Treaty of Versailles over German political changes following WWI, the reparations alone cannot account for all of the changes that occurred. The economic collapse of Germany may have made the German people more susceptible to persuasive political leaders (i.e. Hitler), but the fall of the Weimar Republic and 19 Shirer, William L. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany. New York City: Simon & Schuster, 1960, p53-59, 63-69. 20 Unknown. Versailles Protest. Photograph. London: Mary Evans Picture Library/Weimar Archive, 2013. Unattributed source. http://www.maryevans.com/images/10/06/30/10063062a.jpg (accessed November 8, 2013). See Appendix A. 21 Unknown. Germany 1933. Photograph. London: Mary Evans Picture Library/Weimar Archive, 2013. Unattributed source. http://www.maryevans.com/images/10/06/26/10062676a.jpg (accessed November 8, 2013). See Appendix B. 22 Shirer, William L. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany. New York City: Simon & Schuster, 1960, p53-59, 63-69. 23 Hitler, Adolf. Mein Kampf. Translated by James Murphy. Camarillo, CA: Elite Minds, 2009, Volume II Chapter VI. 9 rise of the Nazi Party cannot be adequately explained by just the ramifications of the reparations imposed on Germany. The political changes in Germany were the culmination of racial, social, and economic unrest and dissatisfaction with the existing German government as well as wider global politics, and while the reparations did affect this change, they are not fully or arguably even mainly responsible. 001394-610 10 Bibliography Bresciani-Turroni, Costantino. The Economics of Inflation: A Study of Currency Depreciation in Post-War Germany. Translated by Millicent E. Sayers. London: George Allan & Unwin, 1937. Dyar, Charles B. "The Youth of Germany." The North American Review 215, no. 799 (June 1922): 739-50. Jstor. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25121056. Fergusson, Adam. When Money Dies: The Nightmare of Deficit Spending, Devaluation, and Hyperinflation in Weimar Germany. New York City: Public Affairs. Hershey, Amos S. "German Reparations." The American Journal of International Law 15, no. 3 (July 1921): 411-18. Jstor. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2188001. Hitler, Adolf. Mein Kampf. Translated by James Murphy. Camarillo, CA: Elite Minds, 2009, Volume II Chapter VI. Robbins, Lionel. Foreword to the Economics of Inflation: A Study of Currency Depreciation in Post-War Germany by Costantino Bresciani-Turroni. Translated by Millicent E. Sayers. London: George Allan & Unwin, 1937. Shirer, William L. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany. New York City: Simon & Schuster, 1960. Unknown. Germany 1933. Photograph. London: Mary Evans Picture Library/Weimar Archive, 2013. Unattributed source. http://www.maryevans.com/images/10/06/26/10062676a.jpg (accessed November 8, 2013). See Appendix B. Unknown. Untitled. Cartoon/Poster. Berlin: The Nazi Party, 1924. From the Mary Evans Picture Library/Weimar Archive reproduction of a Nazi poster. http://www.maryevans.com/images/10/06/90/10069088a.jpg (accessed November 8, 2013). See Appendix C. 001394-611 10 Unknown. Versailles Protest. Photograph. London: Mary Evans Picture Library/Weimar Archive, 2013. Unattributed source. http://www.maryevans.com/images/10/06/30/10063062a.jpg (accessed November 8, 2013). See Appendix A. US Department of State. The Treaty of Versailles and After: Annotations of the Text of the Treaty. Washington, DC.: Government Printing Office, 1944. Modern History Sourcebook. http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/1919versailles.html, Articles 49, 51, 159, 160, 231, and 232. 001394-612 10 Appendix A This is a photograph (from Mary Evans Picture Library) of a Berlin Fotest sometime in the 1920's over the Treaty of Versailles. Both the photographer and the elate are unknown 001394-613 10 Appendix B This is a photograph (from the Mary Evans Picture Library) of 1933 Nazi-lead protest against terms of Treaty of Versailles. One sign (in German) reads “Day of Versailles, Day of Dishonor!” The photographer is unknown. 001394-614 10 Appendix C This is an official Nazi poster (from Mary Evans Picture Library) from 1924. In German it reads “first bread, then reparations,” along the top and urges the viewer to join the NSDAP (the Nazi party) along the bottom of the poster.