Flaming landfill changing waste disposal in the Stans

advertisement

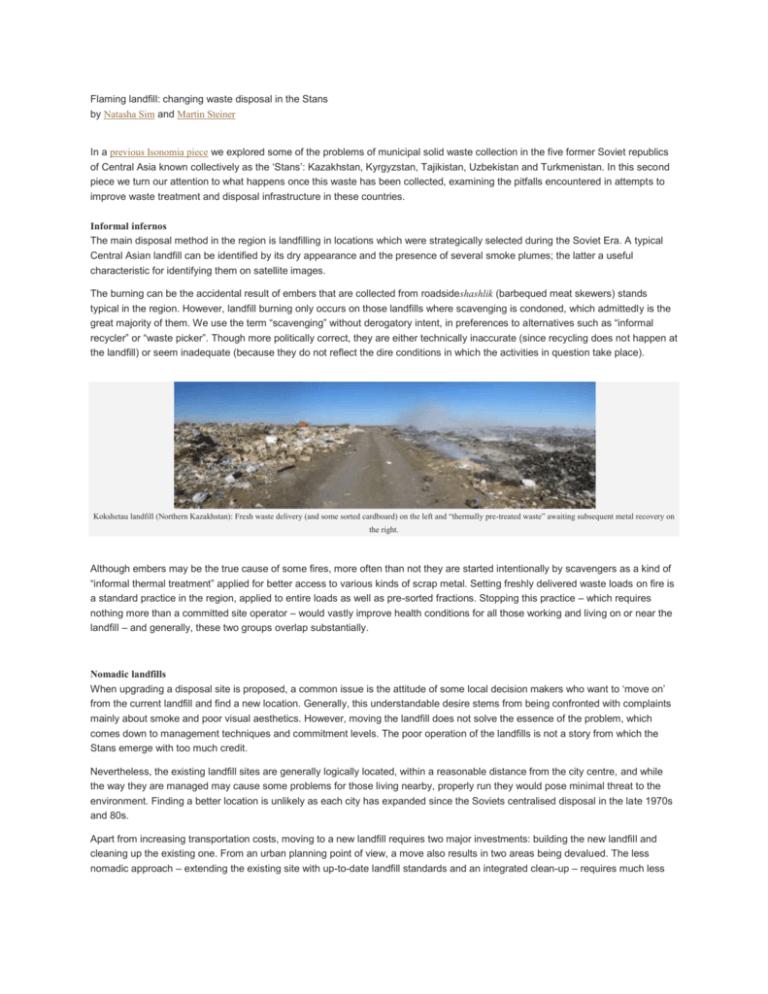

Flaming landfill: changing waste disposal in the Stans by Natasha Sim and Martin Steiner In a previous Isonomia piece we explored some of the problems of municipal solid waste collection in the five former Soviet republics of Central Asia known collectively as the ‘Stans’: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan. In this second piece we turn our attention to what happens once this waste has been collected, examining the pitfalls encountered in attempts to improve waste treatment and disposal infrastructure in these countries. Informal infernos The main disposal method in the region is landfilling in locations which were strategically selected during the Soviet Era. A typical Central Asian landfill can be identified by its dry appearance and the presence of several smoke plumes; the latter a useful characteristic for identifying them on satellite images. The burning can be the accidental result of embers that are collected from roadsideshashlik (barbequed meat skewers) stands typical in the region. However, landfill burning only occurs on those landfills where scavenging is condoned, which admittedly is the great majority of them. We use the term “scavenging” without derogatory intent, in preferences to alternatives such as “informal recycler” or “waste picker”. Though more politically correct, they are either technically inaccurate (since recycling does not happen at the landfill) or seem inadequate (because they do not reflect the dire conditions in which the activities in question take place). Kokshetau landfill (Northern Kazakhstan): Fresh waste delivery (and some sorted cardboard) on the left and “thermally pre-treated waste” awaiting subsequent metal recovery on the right. Although embers may be the true cause of some fires, more often than not they are started intentionally by scavengers as a kind of “informal thermal treatment” applied for better access to various kinds of scrap metal. Setting freshly delivered waste loads on fire is a standard practice in the region, applied to entire loads as well as pre-sorted fractions. Stopping this practice – which requires nothing more than a committed site operator – would vastly improve health conditions for all those working and living on or near the landfill – and generally, these two groups overlap substantially. Nomadic landfills When upgrading a disposal site is proposed, a common issue is the attitude of some local decision makers who want to ‘move on’ from the current landfill and find a new location. Generally, this understandable desire stems from being confronted with complaints mainly about smoke and poor visual aesthetics. However, moving the landfill does not solve the essence of the problem, which comes down to management techniques and commitment levels. The poor operation of the landfills is not a story from which the Stans emerge with too much credit. Nevertheless, the existing landfill sites are generally logically located, within a reasonable distance from the city centre, and while the way they are managed may cause some problems for those living nearby, properly run they would pose minimal threat to the environment. Finding a better location is unlikely as each city has expanded since the Soviets centralised disposal in the late 1970s and 80s. Apart from increasing transportation costs, moving to a new landfill requires two major investments: building the new landfill and cleaning up the existing one. From an urban planning point of view, a move also results in two areas being devalued. The less nomadic approach – extending the existing site with up-to-date landfill standards and an integrated clean-up – requires much less monetary input, by a ballpark factor of 1.5, leaving more resources to invest elsewhere, such as improvements to the collection system. It is usually the “harder sell” but must not be overlooked in a landfill improvement project’s start-up phase. That sinking feeling Landfill projects are not the only disposal schemes where ambition runs ahead of the capability of the creaking systems in the Stans to operate them successfully. Such schemes have a high risk of generating sunken investments, damaging donor reputations, and adding costs for beneficiaries. Companies that struggle with institutional capacity focus mainly on the transportation of waste and not on disposal methods. It is unlikely they will be able to maintain operation of a technically advanced system in an environmentally safe way. Incinerators for stray dogs are an example of prevalent constituents of procurement lists that are almost guaranteed to turn into such losses. However, the underlying reason for becoming a sunken investment is much more fundamental and human: people tend to solve problems only after they start to suffer from them. Currently, nobody suffers from the dead dogs that are deposited at the landfill (where they can be safely buried) and it is therefore likely the beneficiaries will end up preferring to save on the fuel it takes to operate such an incinerator. Ironically, the incinerator itself ends up as a dead dog. Contain yourself: to some eyes, a disposal container in Khujand, North Tajikistan can look like a dwelling. Even something as simple as a move to containerise more waste can run up against local issues in countries so beset with poverty. Large containers have multiple possible uses, and in the picture above the local citizen, to the left in the photo, has confused the disposal container with a private house. Another example of unrealistic expectations is the dream of becoming rich from waste; a common misconception on the part of both donors and beneficiaries, over optimism about the financial rewards of material recovery have made recycling plants a reoccurring item on solid waste management projects’ shopping lists. In Tajikistan, energy saving light bulbs are widely used in even the poorest households. Recently there has been a local wish for the construction of a recycling plant solely dedicated to this specific (moreover hazardous and virtually unrecyclable) perceived problem solver. A recycling plant is often thought of as a modern Western solution that will bring prosperity and popularity when in reality the payback period will exceed the facility’s expected lifespan. The clash between the ambitions of donors and funders and the realities of waste management in the Stans is perhaps best exemplified by the donors’ regular insistence that clients must implement an Environmental Management System (such as ISO 14001). Many donors rightfully expect their investment projects to meet high environmental standards, but fail to see that in the Stans there is an inverse relationship between the emphasis on meeting ‘Western’ environmental standards and the affordability to beneficiaries of implementing them. Though understandable, compliance with ISO 14001 it is much too ambitious for most projects in the Stans, and the attempt to meet funders’ requirements wastes valuable time and effort. Improvement in waste management in the Stans is possible, and there are projects that deliver real benefits. However, both the projects and the standards to which they are held need to be appropriate to their environment and recognise the cultural and social setting in which they are being implemented. The application of less technically ambitious projects and softer standards would create more sustainable solutions at a faster rate, while recognising that it is impossible to leapfrog certain stages of development.