Excerpts from Drafts-in

advertisement

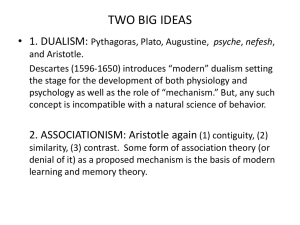

The following are excerpts from a few drafts in progress. Please take a look at each one to get a sense of some of the different things people are doing to address the inquiry prompt successfully. Happy reading! Example #1: Opening of Kendra Gardner’s Inquiry. Notice the way Kendra uses an illustration to establish the focus of the inquiry. With this one image, Kendra points to questions about the existence and “realness” of physical objects, nonphysical ideas, freewill, bodies, and experiences, and then she winds into an indication of the intent of her inquiry. Picture a young war veteran, full of naïve passion and ambition, recovering from shock and trauma on an appointed bed at a hospital: his arm recently amputated. Image the glimmer in this veteran’s eye as he wakes for the first time since battle to discover that he is alive and suddenly feels so parched that he fears a new trauma – death by thirst – and reaches with his right arm to grab a glass of water so close to him. Understand the puzzlement that rips through his body as he is not blessed with water… Had he not willed his arm to move? Had he not felt his fingers lurch forward to sooth his currently rich agony? Later comprehending that his right arm was amputated after an injury he is struck with a serious issue: his arm had moved, it had felt so real, it was Real. Or was it? The once joyful veteran is not the first or the last person to ponder boldly at what stands to be Real and True and what is Real and True. Throughout human history philosophers have argued Ontology and Metaphysics, philosophical topics regarding the nature of existence, reality, and truth. While each argument reasonably explains separate views, one may comprehend and incorporate these arguments to begin a journey in understanding philosophy. Example #2: Opening of Robin Lancaster’s Inquiry Robin accomplishes two things with this opening. First, he establishes a kind of “theme” for his inquiry—a journey into the forest of philosophy. He will use this theme to help him wade through the different questions and ideas. Second, he establishes in paragraph #2 the specific focus of the first section of his inquiry: the questions of metaphysics and ontology. This is a study of questions that philosophers have been trying to answer since the subject first began. The three questions that this essay will deal with will be what is real? How does one know the that the things that we perceive to be real actually? And finally what is the right way to interact with the real things. These questions make up the backbone of philosophy and the great names have often been made by forays into these subjects. Philosophy and these questions in particular are too often the providence of stifling, sweater vest wearing academics with little to no contact with the real world. Yet these questions are vastly important as they help us understand exactly how we view the world which gives us a much better idea of how to proceed. I grew up in two forests, one outside my door and the other inside my mind. Though I have left one forest behind it will be long before I leave the other, and I walk there still every day. So instead of sitting in class and reading from lengthy, dense texts let I invite you to simply take a walk with me. We arrive at the woods, we don’t really remember how we got here and it seems that now there is nothing but trees on all sides. In front of us there is a trail with a nicely painted sign which simply reads “What is real?” We stand at the trailhead looking at the well-worn earth of the trial, many thinkers have stood in this exact same spot. We stand in our hiking boots where the sandaled feet of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle once trod. Where Kant reasoned his way through each step and Mill calculated the ramifications those steps. But none of this history matters because all that remains of those who walked here are their footprints, it is we who will do the actual walking. In order to understand what is real we must first take stock. This is often done by making a list called ontology. However lists are hardly practical for hiking in the forest so instead we shall have a backpack. Armed with our ontological backpack and a bag of trail mix we step onto the trail. Example #3: Opening of Steve Bowman’s Inquiry Steve is deliberately creating a kind of “Socratic-style” inquiry here by taking us through a focused, organized question/answer session with himself. He uses the Socratic method as a way of taking us through the questions and issues of metaphysics and ontology. When I was about two years old, I remember being very upset that the woman who was standing over my crib wasn’t my mother. I was still struggling with object permanence I guess. But that is one of my first memories. It wasn’t a memory of being born, it was a memory from much later. The funny thing is, I can’t remember what happened before that. So how do I know anything happened before that? Maybe I just popped into existence right there in that crib. But I remembered my mom and I knew this woman wasn’t her. So were my memories real even though I can’t remember what made me remember my mom? To figure that out, I first might have to figure out what is real and what exists. But where do I start? Since I’m the one asking the question, I guess I should start with me. Do I exist? A fair question. I could spend years trying to figure that out, but instead, I will use a little test developed by French philosopher and scientist, Rene Descartes. He found that you could prove whether or not you exist by making one simple statement; I don’t exist. I guess it couldn’t hurt to try it. I don’t exist! Well, it must not be a magic trick because I’m still here. It seems if I didn’t exist, there would be no one there to make the statement. So thanks, Rene. So what else exists? Am I alone in the universe? Descartes arrived at that conclusion by being skeptical. He attempted to doubt everything. But he could not doubt his own existence. That became his bedrock of skepticism. He had hit rock bottom and still existed. Example #4: Excerpt from Brittany Carpenter’s Inquiry Body. These paragraphs appear after Brittany has introduced the subject of her inquiry and her intentions. Notice the careful attention Brittany pays to not only explaining very specifically how various philosophers address ontological and metaphysical questions, but also she explains the rationales for addressing the questions in these ways. Once Brittany works in quotations from the philosophical works we’ve studied, these paragraphs will be very strong. In order to answer the first of these questions, what is real and what exists, we must first ask ourselves what it means to say that something exists, and in what ways do these things exist? This is an ontological and metaphysical question that can in a sense, become the foundation upon which other major philosophical questions can be answered and based. In exploring the ontology of the world around us, most all of us would agree that things such as the chair we are sitting on, this paper that you are reading, the burrito you had for lunch, and the shoes in which your feet go are all very "real". We would agree that these things exist because we can see, feel, taste, touch, and smell. We deem these things as real because our sensory data has an experience of it. However, philosophers throughout time such as Descartes believed this was unreliable data in that our senses can deceive us. He reasoned that at any time his sensory experience could be a complete mirage as he could be dreaming and not really perceiving things with his senses at all. Philosophers have dug even deeper into the quest for an ultimate reality, or an ontological explanation for not only the physical world around us, but our internal world, soul, and mind as well. How can we determine that something is "real" when it is something that we do not have sensory data of? How can we determine if justice, love, or truth are real things? Do ideas exist in the same ways that the other items on our ontology such as burritos do? If not, how can we determine how exactly these ideas do exist? Plato presented an extremely vivid picture of what he believed to be transcending levels of reality. In his Allegory of the Cave Socrates paints us the picture of prisoners stuck in the dark glooms of the bottom of a cave. For their whole lives these prisoners have known no reality but the shadows on the adjacent wall, and worshipped these shadows as gods for it was all they had ever known. The truth of the matter was that these puppets were actually depictions being cast by real beings, of things such as trees and horses that existed independent of their shadowy depictions. What Plato is trying to show us is that there are levels of objective reality. Although we may not at any given time see the bigger picture of the real things casting shadows on our lives the depictions that we are perceiving are related to a bigger picture in the whole. Those things that we can perceive with our senses are generally believed to be the most real, but Plato demonstrates to us in The Allegory that those sensory truths are often the most basic form of reality. He believed that things such as ideas, knowledge, justice and love were higher levels of reality, and that the truth of these higher realities could be reached through thought and reason. Descartes reasoned the same question about determining what is real with the conclusion that the only certain thing in the world which is completely justified and free of doubt is the truth that "I exist". Descartes search for the ultimate reality led him to bathe all of his ideas and beliefs in "an acid bath of doubt" to rid himself of any beliefs in which he was not completely justified. Though he was not a "skeptic" or a believer that attaining knowledge is impossible, he embraced the process of the skeptics in order to rid himself of any potentially untrue beliefs. Descartes was a metaphysical dualist, or he believed that there were two kinds of reality, the body as a physical entity and the mind, as a nonphysical or spiritual thing. Descartes believed that the mind and body were two separate entities that interacted in an unknown location. He claimed that he could doubt that his body existed, but he could not doubt that his mind existed. In order to attempt to doubt his mind he determined that you must use your mind to doubt it, this being a contradiction further supported his beliefs. He reasoned that if two things do not have identical properties they are not the same. Since he could doubt one and not the other he determined that the mind and body were not the same. He claimed that the mind is a thing that is self aware, whereas the body is not self aware. In contrast to this position, Physicalism is the claim that the self is identical to or the product of the activities of the body or brain, and that there is no nonphysical aspect of a person. A physicalist would point to the weakness within the dualists argument in the lack of explanation of where exactly this connection between the mind and body takes place. They believe that as soon as you point to a physical place where this interaction takes place you have identified a physical reason for what the dualists claim to be a separate, nonphysical thing. They also point to the question of physical events occurring to the body that ultimately end up changing a persons' mental life. Additionally, physicalists point out the scientific inconsistencies within the dualists claims. If your body is set into motion by a mental even this violates the laws of physics as energy has entered the world and the principle of the conservation of energy is violated as there is the creation of new every with no origin of this creation. For this reason science and the way the world is governed seems to be in coincidence with the physicalists' views. In regards to the question do I exist the physicalist would claim that the non physical mind is not a thing and that we exist only in relation to the physical body. The text describes these views as "the cumulative effect of neuronal interaction is the sort of phenomena we know as consciousness". They believe that our thoughts, feelings and beliefs are a product of our physical bodies' brain that cause us to feel the way that we do, or that our mental events are the same as chemical brain events. The dualist would dispute the physicalists' views with the claim that although measurable brain activity is present when making conscious decisions it does not necessarily mean that the two events occurring together are the same thing. As we can see, both these positions do claim that we exist, though their outlooks regarding the origins and way in which we do exist differ vastly. In addition to the question of whether of not we exist we must then question the existence of our options concerning human freedom. The three main positions surrounding the philosophy of freedom, determination and moral responsibility are the hard determinist, the libertarian and the compatibilist. Example #5: Excerpt from Skylar Stoneman’s Inquiry Body. These paragraphs appear after Skylar has introduced the subject of his inquiry, stated his intentions, and provided some definitions of key terms. Skylar is dutifully citing the page numbers to reference his ideas (good job, Skylar!). Notice in particular how Skylar takes just one idea at a time, explains it completely, and only then moves on to the next idea. He is taking very deliberate effort to ensure that his reader is able to follow him throughout the inquiry. …….Both of these ontological definitions of what is fundamentally real lead to many philosophical viewpoints or positions. But the two main encompassing viewpoints held by philosophers are dualism and physicalism. Dualism is the idea that the body and the mind are separate things, with the mind being the spiritual collection of knowledge and experiences (Lawhead 216). Physicalism is the claim that the thinking mind and body are one and the same and that thought, knowledge, and memory are just the neurochemical signals and neuron pathways in one’s brain (Lawhead 216). Both dualism and physicalism have their individual strength and weaknesses. Dualism depicts us as having a soul, spirit, or essence which follows the more religious viewpoints of individuals. It is also the more comfortable of the two viewpoints since it allows for a belief of life beyond death. Dualism lends itself to the idea that enlightenment or true knowledge can be obtained. One notable supporter of dualism was Rene Descartes who often defended the idea of dualism with his argument of the “Principle of the Nonidentity of Discernables” (Lawhead 221). This argument states that since the mind and body do not have the same properties, then they cannot be identical since all identical things have exactly the same properties. But there is one major problem with dualism though. If the spirit is non-physical and can never be physical, and the body is a very physical entity, then how can the spirit interact with the body? If there is some way for it to interact with the body, where does the interaction occur? Both these questions have yet to be answered by dualist philosophers. Another major flaw in dualism is that every motion or action is driven by force, but the spirit is nonphysical and has no mass. This means that the spirit, by the laws of physics, cannot influence our bodies. If it is energy that the spirit uses move our bodies, then this energy is being produced by a non-material entity, which would violate the law of conservation of energy. This is where the strengths of physicalism come into play. Physicalists state that mental events, such as thoughts and memories, and brain states are one in the same. If we feel happiness, it is because our physical brain is producing extra serotonin, giving us the feeling of happiness. Memories are just the collection of electrochemical paths created by neurons. Our brain and the way it is structured is who we are, no more, no less. With mental events and brain states being the same thing, no physical laws are being violated and the location of consciousness is known to be just in the brain. Even though it is an elegantly simple explanation of what makes us who we are, there are some problems with physicalism. One such problem is brought up the german philosopher Gottfried Leibnitz, who pointed out that if a machine had the ability to perceive, calculate and produce and output based on that sensory data will still not be considered to have a consciousness (Lawhead 243). But physicalism in general describes are actions as just imput-output machines with our brains as the central processor. If we are hungry, the signal from our stomach goes to our brain, which then produces the overall signal of discomfort that we would consider hunger. But we are more than just input-output machines. Our consciousness perceives more than that and we can contemplate what it means to be hungry and how hunger will affect our lives and the lives of others. The ideas of physicalism and dualism also apply to freedom of will and determinism. Determinism is the idea that all of our current and future actions are the results of previous…..