Physical Risks

advertisement

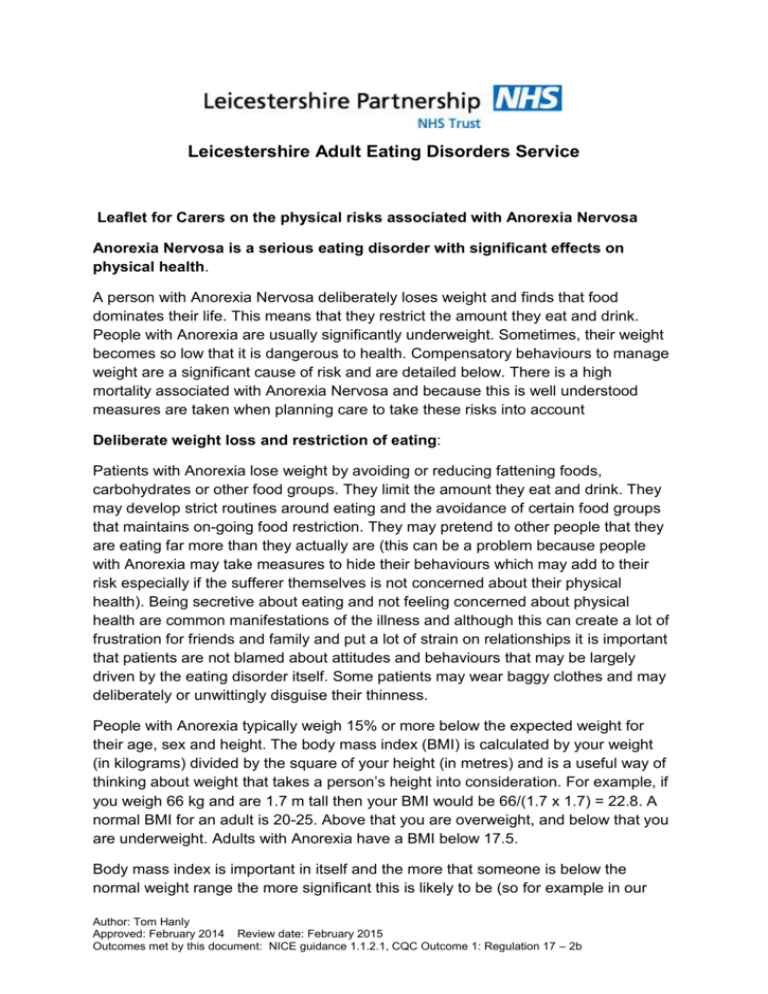

Leicestershire Adult Eating Disorders Service Leaflet for Carers on the physical risks associated with Anorexia Nervosa Anorexia Nervosa is a serious eating disorder with significant effects on physical health. A person with Anorexia Nervosa deliberately loses weight and finds that food dominates their life. This means that they restrict the amount they eat and drink. People with Anorexia are usually significantly underweight. Sometimes, their weight becomes so low that it is dangerous to health. Compensatory behaviours to manage weight are a significant cause of risk and are detailed below. There is a high mortality associated with Anorexia Nervosa and because this is well understood measures are taken when planning care to take these risks into account Deliberate weight loss and restriction of eating: Patients with Anorexia lose weight by avoiding or reducing fattening foods, carbohydrates or other food groups. They limit the amount they eat and drink. They may develop strict routines around eating and the avoidance of certain food groups that maintains on-going food restriction. They may pretend to other people that they are eating far more than they actually are (this can be a problem because people with Anorexia may take measures to hide their behaviours which may add to their risk especially if the sufferer themselves is not concerned about their physical health). Being secretive about eating and not feeling concerned about physical health are common manifestations of the illness and although this can create a lot of frustration for friends and family and put a lot of strain on relationships it is important that patients are not blamed about attitudes and behaviours that may be largely driven by the eating disorder itself. Some patients may wear baggy clothes and may deliberately or unwittingly disguise their thinness. People with Anorexia typically weigh 15% or more below the expected weight for their age, sex and height. The body mass index (BMI) is calculated by your weight (in kilograms) divided by the square of your height (in metres) and is a useful way of thinking about weight that takes a person’s height into consideration. For example, if you weigh 66 kg and are 1.7 m tall then your BMI would be 66/(1.7 x 1.7) = 22.8. A normal BMI for an adult is 20-25. Above that you are overweight, and below that you are underweight. Adults with Anorexia have a BMI below 17.5. Body mass index is important in itself and the more that someone is below the normal weight range the more significant this is likely to be (so for example in our Author: Tom Hanly Approved: February 2014 Review date: February 2015 Outcomes met by this document: NICE guidance 1.1.2.1, CQC Outcome 1: Regulation 17 – 2b service we would be very concerned about any patient with a BMI lower than 15 and we might strongly advise a patient not to drive at this weight for example). However other factors need to be taken into account too. The rate at which weight is lost is an important factor. Ideally it is best if a patient can stabilise their weight or manage to restore their weight towards a normal range and weight loss especially if consistent is always a concern. As a rule of thumb weight loss of 0.5-1kg per week is significant but weight loss in excess of 1kg per week should raise a red flag and a patient with this degree of weight loss needs to be carefully monitored by health care professionals either the GP or an eating disorder professional. The rate of weight loss is to some degree associated with the body’s capacity to adapt to the changes and more rapid weight loss is more usually associated with increasing physical symptoms. Patients are very individual and two patients at the same BMI may be very different in how they present in terms of physical health. Only a thorough medical assessment can determine how unwell and therefore how at risk a patient is. Compensatory behaviours: Patients may be using other ways of staying thin such as exercising too much, vomiting, taking laxatives, taking appetite suppressant, diuretics (water tablets) or recreational drugs that promote loss of appetite such as cocaine or amphetamines. The use of these compensatory mechanisms often a response to a subjective sense of having eaten more than one intended, add to the risks from dietary restriction. Patients using several compensatory behaviours are at increased risks of physical health problems, that is the risk accumulates with each new behaviour. Self-induced vomiting can be very dangerous. The body responds to vomiting by lowering a chemical called potassium which has a key role in the function of nerves. At worst this can affect the nerves of the heart causing irregular heart rhythms and sometimes sudden collapse and death. Many patients with eating disorders believe that they can tell when their potassium levels are low because they may experience muscle weakness and muscle cramps. Although this may be true in some cases levels of potassium can be very low without physical symptoms so there is the danger of being falsely reassured by feeling well. Patients who engage in regular vomiting especially if this is at least daily should have regular blood testing to estimate their blood potassium levels (weekly or more frequently). Vomiting can also cause dehydration which can worsen the problem. Replacement treatment can be given to manage the problem with potassium supplements while the patient works on changing this behaviour: managing the risks to physical health is paramount. Misusing laxatives can also affect hydration and the acid base balance of the body and in itself may be less immediately dangerous than vomiting. However when combined with vomiting it is much more dangerous and in longer term use laxative Author: Tom Hanly Approved: February 2014 Review date: February 2015 Outcomes met by this document: NICE guidance 1.1.2.1, CQC Outcome 1: Regulation 17 – 2b misuse can permanently damage the function of the bowels but also in some cases cause irreversible damage to the heart. Patients may feel compelled to exercise to manage their weight and may pursue punishing levels of exercise in spite of low energy levels and feeling physically poorly. Signs that exercise may be out of control are that it interferes with other day to day activities; it is prioritised above other things including social contacts, work, hobbies etc., it is very routine bound with exacting rules, the patient may exercise in spite of injury and often exercise ceases to be enjoyable and is experienced as a chore. Exercise may take the form of excessive activity, being unable to sit or relax etc. Other physical symptoms: Patients often complain of having less energy, being unable to do physical tasks that were previously managed such as lifting things, climbing stairs (the patient may stop several times or need to pull themselves up using the hand rail which is a significant sign of reduced muscle power), managing walking on an incline, feeling washed out after routine activities of daily living that would not be expected to cause such problems such as dressing. Sometimes patients become restless and fidgety; they may struggle to relax or settle in spite of low energy levels (this may be a manifestation of semi-starvation). Patients may complain of the cold and wear several layers of clothes or insist that the house is kept very warm. Their skin may be dry, their hair thinning, falling out or lacking life and nails may be broken or damaged. Patients who vomit may damage their teeth and should seek dental advice. Chest pain or tightness, shortness of breath at rest or on exertion, palpitations (a sensation of the heart thumping or beating irregularly) may be signs of heart problems and should always be taken very seriously. Those who restrict and who do not eat regularly may have several digestive problems; they may feel full easily and bloated especially after meals, they may feel nauseous and complain of indigestion or tummy ache. They may lose their regular bowel habit and typically may be passing stool much less often reflecting the smaller loading of food on the gut. Some patients report finding it hard to delay urinating or having to pass urine more frequently as the muscles maintaining the bladder weaken and in some cases patients have reported incontinence. Menstrual functioning may be affected with lighter of less frequent menstruation or total cessation and this may have implications for bone health and density. Author: Tom Hanly Approved: February 2014 Review date: February 2015 Outcomes met by this document: NICE guidance 1.1.2.1, CQC Outcome 1: Regulation 17 – 2b Patients with Anorexia may suffer anaemia from dietary deficiencies or other issues related to the lack of nutrients and changes to blood cells may mean that the capacity to fight infections is lessened. Patients may complain of feeling dizzy and this might be related to low blood sugars or dizziness on changing position which is usually a sign of low blood pressure the result of low weight and loss of muscle mass. How can you help with these issues? A full discussion of the supporting role of carers and family is not within the scope of this leaflet but these issues are comprehensively discussed in “skills based learning for caring for a loved one with an eating disorder-the new Maudsley method” by Janet Treasure and co-writers published by Routledge which is highly recommended to you. This is available on the ward to loan but is worth buying as a reference to return to as required. This book covers issues concerning the wider issues of supporting a loved one with Anorexia including physical health issues. Caring for someone with an eating disorder means that you may be spending a significant amount of time with the patient and be in a good position to notice changes to physical health. Things to look out for include the emergence of new physical symptoms or worsening of current symptoms. Some patients who have been unwell for some time can get so used to feeling unwell that they take this as their normal state and may not be alarmed or worried and are at risk of underestimating the seriousness of their symptoms. You may notice significant changes to eating, weight or other behaviours and you may be well placed to alert others including professionals that help is needed or a situation is deteriorating (in the first instance concern should be raised with the patient who should be encouraged to seek help themselves but with more serious concerns you may need to take the initiative especially if the patient is unable to act in their own best interests). In some cases it may be necessary to over-ride the wishes of the patient and this can be difficult and impact on relationships. Nonetheless, it is not reasonable as a carer to have to carry and bear very high levels of concern about the patients’ health nor should you be expected to exercise the judgement of a health professional. In that sense your primary task is to notice and raise the alarm. Ultimately it is the patient who must take responsibility for their physical well-being and many patients will appreciate positive intentions to help even if they cannot appreciate this in a crisis. Author: Tom Hanly Approved: February 2014 Review date: February 2015 Outcomes met by this document: NICE guidance 1.1.2.1, CQC Outcome 1: Regulation 17 – 2b