PEDRO DE MENA Y MEDRANO (Granada, 1628 – Malaga, 1688

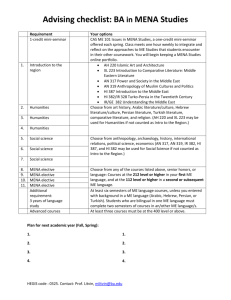

advertisement

PEDRO DE MENA Y MEDRANO (Granada, 1628 – Malaga, 1688) “The Virgin of Solitude” 1660s Carved, polychrome wood. Image, 53 cm high. Base, 3cm high This bust of a woman with a sad, serene and pale face makes use of a frontal, symmetrical composition. It includes the head, shoulders and upper part of the torso, all covered by a white veil and pale blue mantle. The only elements that are not completely symmetrical are the slight inclination of the head towards its left, the number of folds in the veil and the breadth of the mantle falling on each side. Were it not for its religious significance and devotional purpose, this could be a genre depiction of woman stoically enduring extreme suffering, given that the image lacks any symbolic and iconographic elements that would enable the viewer to identify the subject. It was this realist language and extremely naturalistic and accessible type of depiction that captivated Pedro de Mena’s clients. The artist expressed religiosity through restrained emotions and poses, concentrating his expressive resources on the image’s head through the expression of the face, eyes and mouth. It was Pedro de Mena who popularised life-size or small-scale bust-length sculptures, normally displayed in urns or glass display cases, as they are referred to in some posthumous inventories. The fact that they were enclosed in such cases, with a wooden backboard and the other three sides of glass, has meant that they are often well preserved. Busts of Christ and the Virgin were commissioned from all over Spain and even from South America, including places such as Lima and Mexico, as well as other European locations including Vienna. From his studio in Malaga this Granada-born sculptor produced a large number of busts of the Virgin Dolorosa, some as individual figures and others forming pairs with Ecce Homos. Mena’s sculptures can be classified as falling into three groups: 1 short, bustlength images that represent the head and start of the bust, focusing attention on the face, as in the present image; and two different half-length or prolonged bust formats, one with the figure truncated at the height of the breast but including the hands, such as the Virgins in the church of La Victoria in Malaga and in Cuenca cathedral, and another type that has the bust cut off below the hips and which includes the arms with the hands joined or separated. This latter type has a more dramatic expression, for example the two in the convent of the Descalzas Reales in Madrid. This year (2014) marks the 100th anniversary of the publication of the first monograph on Pedro de Mena, written by the Malaga-born art historian Ricardo de Orueta. 2 Among the works that he catalogued, the only bust-length Virgin Dolorosa without arms is the one that was in the collection of José Lázaro Galdiano and which the present author identified as this Virgin of Solitude. 3 Since Orueta’s text, various studies and exhibitions have allowed for a better appreciation of the merit of this sculptor’s work, his extensive outlet, the importance of his clients and the influence he exercised on artists of his own day and on subsequent generations active in Malaga, Granada and Madrid. Twenty years after the identification of this work, Professor Diego Angulo published another very similar version that formed a pair with an Ecce Homo which he saw in the sacristy of the Jesuit church of La Profesa in Mexico City, now the church of San Felipe Neri. 4 This second Virgin has the face of a much younger woman with her eyes raised. In his article Angulo compared the present Dolorosa with the one in the Lázaro Galdiano collection and completed his commentary by referring to the existence of another similar pair in the church of San Luis in Seville, also a former Jesuit church. With regard to the theme of the Virgin Dolorosa, fifty years after Orueta’s publication Professor Emilio Orozco analysed this iconography and the expressive resources deployed by Mena, 5 also discussing the devotional function of bust-length images of this type of Virgin and drawing a distinction between the Virgin Dolorosa and the Virgin of Solitude. 6 It is now considered that these different depictions reflect the Virgin at different times during the Passion of Christ: Suffering, Anguish, Mercy and Solitude. The number of images of the Virgin Dolorosa and the Virgin of Solitude attributed to Mena have increased over the past century with the growing number of studies on the artist. There are four known images that form pairs with an Ecce Homo (former Jesuit churches in Seville, Mexico City 7 and Lima, Peru); convent of the Descalzas de la Piedad in Cadiz; 8 the church of the Palace of San Telmo, Seville; and the Museo Diocesano and Catedralicio, Valladolid. 9 The other versions are individual ones: in addition to the present one, they are to be found in: the church of San Nicolás in Madrid, 10 the church of the Holy Trinity in Vienna, 11 the Museo Nacional de Escultura in Valladolid, 12 the Museo Conventual de las Descalzas in Antequera (Malaga), 13 the Basilica del Gran Poder in Seville, and one in a private collection. 14 Presented frontally, these youthful Virgins have half-open mouths with their eyes (either open or half closed) looking upwards, with the exception of the present example, which is older, looks down and reveals a higher quality modelling. These busts are all approximately 50cm high except the ones in the church of the Palace of San Telmo, which are smaller. In addition to this list of wood, polychrome figures, reference should also be made to a pair of small-scale, carved ivory busts of the Dolorosa and Ecce Homo. These are in the style of Pedro de Mena but are of average quality (Museo Nacional de Artes Decorativas, Madrid). The origins of this type of bust have been explained in different ways but art historians agree that it represents a Baroque updating of 16th-century models. Diego Angulo was the first to note with regard to these images that Mena “preferred the Renaissance bust type.” Emilio Orozco pointed to precedents in the vigorous realism of the figures painted by the Carthusian Sánchez Cotán, the half-length reliquary figures carved by Mena’s father Alonso de Mena y Escalante, and the versions modelled by the García brothers 15 and by the Sevillian sculptor Gaspar Núñez Delgado. Orozco did not refer to all of Mena’s Dolorosas nor to the present version as his discussion focused on the small-scale image of the Virgin of Solitude that the Spanish State had acquired for the Museo de Bellas Artes in Granada. It is possible that Mena was familiar with the half-length Virgins painted by Titian, El Greco and Luis de Morales, but only El Greco depicted her in the short bust format without arms and wearing a blue mantle and white veil. Nonetheless, for the present author the precedents closest to Pedro de Mena are the Dolorosas by the García brothers, Granada-born sculptors active in that city in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, who produced pairs of relief busts of the Ecce Homo and Dolorosa (Ricardo Sierra collection, Seville; and Galería Coll y Cortés, Madrid). These sculptures allow us to correct the opinion of the art historian María Elena Gómez-Moreno in her study of the iconography of Mena’s works when she states that: “We thus arrive at the final subject: the Virgin Dolorosa, which has no precedents in sculpture from Granada.” 16 Orueta only catalogued a single short-length bust of what he termed the Dolorosa type, which is in fact the present version, at that point in the collection of José Lázaro Galdiano. While the present-day Museo Lázaro Galdiano is based on part of his collection, this sculpture did not enter its collections. Orueta described it as a “beautiful sculpture, conceived in a monumental manner and with such serene majesty. The drapery, which is perfectly observed, falls in a simple, natural manner. This is a very beautifully realised work.” 17 The sculpture conveys the Virgin’s solitude after the death of her son. This is the moment just after Christ’s burial when his mother is prostrate with grief. Her face reflects her exhaustion following such great suffering. The three tears that fall down each cheek were added in the last restoration, despite not being visible in the old photograph published by Orueta. Mena does not include the hands joined in prayer with the weeping eyes that witnessed the suffering of the Virgin’s son, nor the arms outstretched in a gesture of supplication for him. Rather, the artist has reduced the expressive element not only to a state of solitude but also to a simple, modest depiction, using a frontal format and omitting any element that might distract the attention of those praying before this image. The Virgin’s head, which is slightly elongated and has a pointed chin, is framed by her brown hair, by the white veil that meets at its two lower points in the centre of the lower part of the bust, and by the blue mantle that flanks the image, falling vertically at its lower edge and revealing the veil and the curved neck of the tunic. The Virgin’s face is serious, possibly the most serious depicted by the artist. The skin is created through soft modulations in the cheeks and on the lips, while her almost closed eyes define a sinuous line framed by the swollen eyelids. The slightly pointed eyebrows, with a faint line between them, emphasise her sadness. The eyes are made of glass and the sculpture still shows traces of the eyelashes on the upper eyelids. Her hair clearly reflects Mena’s style: dark brown and close to the head, with a centre parting that also functions to frame the face. The figure wears the typical white veil and blue mantle of Mena’s Virgins. The mantle is extremely naturalistically carved, its ample, voluminous folds narrowing to a crease at the front and to a beautifully finished area of large, soft folds on the back. In addition, the rest of the mantle adapts itself to the form of the shoulders in an extremely soft manner. The outstanding quality of the back reveals how, despite the fact that the image was intended to be seen from the front and displayed in an urn with a closed back, Mena focused on the smallest details of his sculptures, which are thus worthy of being seen from all viewpoints. The front view reveals the artist’s skill in creating empty spaces between the mantle, the veil and the Virgin’s head, which he achieved by separating the entire head and the clothing into two blocks, a back and a front one, which he positioned, joined and stuck to the head once he had carved and polychromed it. This technique results in a highly realistic effect, creating depth around the head and thus producing a range of shadows and a crepuscular effect depending on the intensity of the light falling on the image. The tunic is purplish in tone with the remains of painted decoration. However, this is very probably an alteration of the aubergine red habitual in Mena’s Virgins. There is no information to confirm that Mena executed the polychromy of his sculptures, but we do know that his images have a characteristic painted finish, from which it is possible to deduce that if he did not paint them himself, he fully supervised the final results. For the clothing of this Virgin of Solitude, Mena combined various textiles, as in his other Virgins, contrasting the heavy texture of their smooth surface and broad folds with that of the white wool veil. For the latter, the artist created the texture of the weave with small drops of oil pigment that produce a detailed linear and horizontal relief. This sculpture can be considered a magnificent image of the Virgin in her solitude, in which the artist achieved an enormous degree of expressivity through a pairing down of resources. The distant, lowered gaze and flaccid face, almost devoid of striking features, conveys the sense of exhaustion after prolonged weeping. Due to this soft modelling of the face, the sculpture should be dated to the 1660s and the present author agrees with Orueta that it was made between the Virgin of Bethlehem in the conventual church of Santo Domingo in Malaga and the Calvary group in the former Jesuit church of the Casa Profesa in Madrid (subsequently the cathedral of San Isidro), both of which were lost in the political and military upheavals of 1931 and 1936. We know now that Mena carved the latter in 1671 for the Colegio Imperial of the Jesuits in Madrid, whose church became the cathedral of San Isidro in the 19th century. 18 For this reason Lázaro Gila’s suggestion that the short-length bust Dolorosas date from the end of the artist’s career, between 1679 and 1688, should be rejected. Pedro de Mena’s Virgin Dolorosa and Virgin of Solitude figures should be distinguished from those made by José de Mora (Granada, 1642-1724), who produced other versions of this image. Thirteen years younger than Mena, Mora was also a pupil of Alonso Cano. He carved bust-length images of the Virgin without arms of the Dolorosa or Solitude type. Examples include the one in the Museo de Bellas Artes de Granada, following the Virgin of Solitude type of the Order of Minims, 19 and the one in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. 20 However, Mora’s Virgins have more expressive faces and his modelling is softer and more sinuous. When analysing Mora’s Dolorosa figures in conjunction with the exhibition on Pedro de Mena held in Malaga, Professor Sánchez-Mesa of the Museo de Bellas Artes de Granada defined the formal traits of these two Granada-born artists: “Mora’s Dolorosas become poetic through their idealisation and soft forms, and Mena’s through their piercing, direct realism, using a smoother, harder modelling.” In conclusion, the formal features of this magnificent Virgin of Solitude correspond to the style of Pedro de Mena y Medrano while its quality and type of modelling allow the work to be dated to the 1660s. Finally, this is the only known version to date with the gaze lowered and depicting the Virgin as an older woman in comparison to the young girls of the other versions. Fig.1 Fig.2 1.- ROMERO TORRES, José Luis: “Dolorosa, Pedro de Mena y Medrano, Iglesia de la Victoria, Málaga”, in El Esplendor de la Memoria. El Arte en la Iglesia de Málaga, exhib. cat., Sala de Exposiciones del Palacio Episcopal de Málaga. Seville, Consejería de Cultura de la Junta de Andalucía, 1998, pp. 182-183, cat. 50. GILA MEDINA. Lázaro: Pedro de Mena. Escultor (1628-1688). Madrid, Arcos Libros, 2007, pp. 183-184. María Elena Gómez Moreno studied Mena’s iconography but did not clearly categorise the different models of the Virgin Dolorosa that she described. GÓMEZ-MORENO, María Elena: “Pedro de Mena y los temas iconográficos”, in Pedro de Mena. III centenario de su muerte, 1688-1988, exhib. cat., Malaga, Consejería de Cultura de la Junta de Andalucía, 1989, pp. 94-95. 2.-ORUETA Y DUARTE, Ricardo: La vida y la obra de Pedro de Mena y Medrano, Madrid, Centro de Estudios Históricos, 1914. That same year Orueta expanded his catalogue of Mena’s works in an article published in an art magazine. ORUETA Y DUARTE, Ricardo de: “La vida y la obra de Pedro de Mena y Medrano”, Museum (Barcelona), vol. 4, no. 4 (1914), p. 142. 3.- While María Elena Gómez Moreno, Lázaro Gila and other experts refer to this Virgin as the work in the Museo Lázaro Galdiano, according to that museum the sculpture did not enter its collections from that of José Lázaro Galdiano. 4.-ANGULO ÍÑIGUEZ, Diego: “Dos Menas en Méjico. Esculturas sevillanas en América”, Archivo Español de Arte y Arqueología, vol. XI, 1935, pp. 132-136, fig. 1. 5.-OROZCO DÍAZ, Emilio: “Devoción y barroquismo en las Dolorosas de Pedro de Mena”, Goya, no. 52 (1963), pp. 235-241. 6.-GUTIÉRREZ DE CEBALLOS, Alfondo R.: “La literatura ascética y la retórica cristiana reflejados en el arte de la Edad Moderna: el tema de la Soledad de la Virgen en la plástica española”, in Lecturas de Historia del Arte. Vitoria-Gasteiz, Ephialte, 1990, pp. 8688. 7-ANGULO ÍÑIGUEZ, Diego: “Dos Menas en Méjico. Esculturas sevillanas en América”..., pp. 132-136, fig. 1. 8.-BANDA Y VARGAS, Antonio de la: “Dos obras de Pedro de Mena en las Descalzas de la Piedad”, Boletín del Museo de Cádiz, no. 2 (1979-1980), pp. 87-88. 9-GARCÍA DE WATTENBERG, Eloisa: “Virgen Dolorosa. Pedro de Mena, atribución”, in Pedro de Mena y Castilla, exhib. cat., Valladolid, Museo Nacional de Escultura, 1989, pp. 42-43. 10.-GÓMEZ-MORENO, María Elena: “Pedro de Mena y los temas iconográficos”…, p. 95. 11.-PÉREZ SÁNCHEZ, Alfonso Emilio: “Piezas inéditas y nuevas consideraciones sobre la interpretación estética de Pedro de Mena a comienzos de nuestro siglo”, in Actas del Simposio Nacional Pedro de Mena y su época. Malaga, Consejería de Cultura, 1989-1990, pp. 308-309. 12.-HERNÁNDEZ REDONDO, José Ignacio: “Dolorosa. Taller de Pedro de Mena”, in Pedro de Mena y Castilla, exhib. cat., Valladolid, Museo Nacional de Escultura, 1989, pp. 4647. 13.-ROMERO BENÍTEZ, Jesús: El Museo Conventual de las Descalzas de Antequera. Antequera, 2008, pp. 49 and 51. 14.-JIMÉNEZ, María Teresa: “Unas obras desconocidas de Pedro de Mena”, in Actas del Simposio Nacional Pedro de Mena y su época. Malaga, Consejería de Cultura, 1989-1990, pp. 444-446. 15.-OROZCO DÍAZ, Emilio: “Los hermanos García, escultores del Ecce Homo”, Cuadernos de Arte (Granada), 1934. 16.-GÓMEZ-MORENO, María Elena: “Pedro de Mena y los temas iconográficos”…, p. 94. 17.-ORUETA Y DUARTE, Ricardo: La vida y la obra..., pp. 154-155, fig. 49. 18.-LLORDÉN, Padre Andrés: Escultores y entalladores malagueños. Ensayo histórico documental (siglos XV-XIX). Ávila, Ediciones Monasterio El Escorial, 1960, pp. 125-126. 19.-SÁNCHEZ-MESA MARTÍN, Domingo: “Dolorosa, José de Mora, Granada, Museo de Bellas Artes”, in Pedro de Mena. III centenario de su muerte, 1688-1988, exhib. cat., Malaga, Consejería de Cultura de la Junta de Andalucía, 1989, pp. 136-137. 20.-TRUSTED, Marjorie: Spanish sculpture. Catalogue of the post-medieval Spanish in wood, terracotta, alabaster, marble, stone, lead and jet in the Victoria and Albert Museum. London, Victoria and Albert, Museum, 1996. JOSÉ LUIS ROMERO TORRES Art historian and curator of cultural heritage