Why Establish Rules and Routines?

advertisement

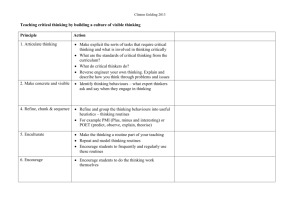

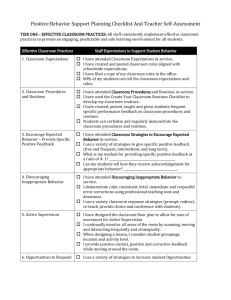

Rules and Routines Overview Defined rules and routines are important components of educational programming for all students, but particularly for individuals with ASD, whose learning differences may present challenges in understanding expectations (Swanson, 2005). This module presents strategies for designing and implementing rules and routines to support students with ASD and promote success in school, home, and the community Pre-Assessment Pre-Assessment Rules and routines support individuals with ASD by addressing which of the following characteristics? Select an answer for question 371 Rules and routines are two different strategies for establishing behavioral boundaries and expectations. Select an answer for question 372 The structure and predictability of rules and routines allow individuals with ASD to manage information and meet the expectations of an environment. Select an answer for question 373 Rules should be: Select an answer for question 374 Routines can help support the development of functional skills. Select an answer for question 375 Rules and routines are more comprehensible when paired with visual supports. Select an answer for question 376 Why Establish Rules and Routines? Unique learning needs, including differences in attention, organization and sequencing, independent initiation, transitioning, and interpreting social cues between activities, often cause individuals with ASD to miss out on important information and activities that occur throughout the day. The next section details some of the specific characteristics that necessitate well-structured rules and routines. Attention Individuals with ASD often demonstrate a myriad challenges related to attention. Quill (2001) highlights problems with engaging and disengaging attention, which ultimately affect attention-shifting skills. Another issue related to attention is over-selectivity, or the tendency to attend to a limited number of environmental cues at one time (Reed & Gibson, 2005). These differences in attention may influence an individual's ability to meet expectations across environments throughout their day. Organization and Sequencing Differences in organizing and sequencing information may impair the ability of individual with ASD to initiate and complete steps in an activity. For example, they may not be able to determine how to approach a situation, identify exactly what needs to be done, and set an appropriate goal or plan (Carnahan, Hume, Clarke, & Borders, 2009). Independent Initiation The National Research Council (NRC) (2001) identified personal independence as a key component in instruction for individuals with ASD. However, individuals with ASD often need high rates of adult prompting or supervision and are susceptible to developing a pattern of waiting for prompts before initiating tasks (Hume & Odom, 2007). Prompt dependence interferes with the development of skills like initiation that support independent functioning. Difficulty with Transitions Transitions between events, locations, and people often present significant challenges for individuals ASD. Environments that provide clear expectations and predictable routines promote increased engagement and on-task behavior (Tien & Lee, 2007), so the new expectations and changes that come from transitions can produce anxiety for individuals with ASD. Difficulty Interpreting Social Cues Monitoring behavior often requires interpretation of social cues. Attention and response to such cues requires abstract and conceptual thinking, skills that are often challenging for individuals with ASD. Therefore, interpreting dynamic social situations, such as those in the school environment, and determining an appropriate behavioral response can present a considerable challenge for individuals with ASD (Hodgdon, 2005). courtesy of Mayer Johnson Individuals with ASD thrive in well-organized, highly structured environments (see AIM module on Structured Teaching for more information). Rules and routines are important components of such learning environments. The predictability of clearly defined rules and routines promotes understanding and participation. Specifically, individuals with ASD may rely on rules and routines to reduce confusion, to make predictions about an event, and then to meet the expectations of the environment (Schuler, 1995). This, in turn, frees individuals with ASD to shift attention to other information, such as instruction, work tasks, and/or environmental cues. When they can better attend to, organize, sequence, and store information, individuals with ASD can later access and apply that information for meaningful purposes. Further, when better able to manage information, individuals with ASD encounter fewer challenges related to transitions and increased levels of independent initiation. Being responsive to the needs of individuals with ASD requires developing and explicitly teaching rules and routines that facilitate participation in many different environments. Without explicitly taught routines, individuals with ASD may develop their own, which are often not adaptive or effective (Mesibov, Shea, & Schopler, 2005). Meaningful and functional rules and routines, in combination with visual schedules and many other organization tools, assist individuals with ASD in understanding the environment and becoming more flexible (Swanson, 2005). Developing and Teaching Rules and Routines courtesy of Mayer Johnson Differences Between Rules and Routines Rules and routines are not the same. Each is a different strategy for establishing behavioral boundaries and expectations. Rules are statements defining behavior permissible in given situations or environments, whereas routines detail the steps required in carrying out certain actions. For example, a rule in the home environment may be that an individual, Johnny, can answer the telephone when it rings. A routine establishes the steps involved when Johnny answers the phone (pick up the phone from the base, press the "talk button," say "hello," wait for a response, etc.). Together rules and routines meet the needs of individuals with ASD, thereby promoting independence and success in many different environments. Visual picture sets are available online to support development of rules and routines at a variety of places, one of those on the Special Education Technology of British Columbia website. Developing and Teaching Rules In order to explicitly teach individuals with ASD to follow the rules across environments throughout the day, it is important to understand the levels of rules they may encounter. Parents may enforce a specific set of rules at home, whereas community and work settings operate under certain rules. Most schools establish a broad set of building-wide rules for students to follow. At the same time, individual teachers establish different sets of rules for each of their classrooms. To complicate matters even more, there are also different rules for certain areas of the school environment, such as the playground, the cafeteria or the library. Since individuals with ASD navigate many different environments during the day, initially identifying one broad set of rules that applies across settings can help promote success. Once they demonstrate understanding of and proficiency in following the broad set of rules, establishing other environmental rules is helpful. Implementing a limited number of concrete rules is important when developing rules. Rules should be observable and clearly illustrate what the student SHOULD do, rather than simply what not to do. A rule such as "no hitting" does not provide any information about what is desired or appropriate. Alternately, "keep hands to self" or "keep hands on the table" specifically describes the appropriate behavior. After identifying which rules to teach, it is important to determine how to deliver instruction. Specific steps include identifying who will provide explicit instruction, the location of instruction, and the instructional strategies and supports needed. Family members, teachers, paraprofessionals, related-service providers, and peers can deliver instruction related to specific behavioral expectations of rules. Teaching occurs in each of the environments where the rules apply in order to promote generalization. Explicit teaching of each rule minimizes confusion and supports independence. For example, a teacher may establish the rule "use nice words" as an expectation in her classroom. Without direct instruction, an individual with ASD may not understand the categorization of "nice words" versus "not nice words." courtesy of Mayer Johnson Providing individualized visual supports, such as picture representations or written copies of the rules, can enhance instruction as well as provide students with an accessible reference. Individuals with ASD need multiple opportunities for practice in a variety of environments. Instruction should include ongoing monitoring and data collection to provide students with specific feedback about performances in practice and real situations. Finally, consistency of enforcement is important. Variations between individuals can cause confusion and limit the potential for the student to understand and follow the rules. For example, a school rule may be "walk in the hallways." A paraprofessional working with Sara, an individual with ASD, insists that she walk. Meanwhile, her classroom teacher allows her to skip or run. This discrepancy makes it unlikely Sara will learn to consistently follow the rule. Developing and Teaching Routines As with rules, an essential first step in developing routines is determining the role of routines throughout the day and across environments (i.e., home, school, and community). This includes analyzing current routines, the individual's adherence to routines, and the amount of previous direct instruction on routines. Analysis of an individual's day may highlight challenging areas where implementation of new routines could create more successful experiences. Carefully consider less structured times such as transitions or free time that may demand implementation of routines to provide more structure. When individuals with ASD transition to a new activity, independent work tasks for instance, beginning the activity may be challenging for them. However, often they are able to complete a task independently once given a prompt to initiate. One strategy to address this challenge is to provide a routine for independent work that clearly outlines the steps required to begin and complete a task. This involves careful analysis of each step to ensure that the individual is able to progress independently. Omitting a step may cause the individual to become "stuck," or unable to move forward on the task independently. A visual representation of the steps in the routine can support direct instruction and provide an accessible reference once independence is expected. The same strategy applies to group instruction or activities. Routine is inherent in many group activities, but without explicit instruction, an individual with ASD may not recognize the pattern. Additionally, creating, teaching, and practicing routines related to less common events, such as emergency drills, can lessen anxiety and develop skills for performance during the event. Such preparation can minimize the occurrence of unsuitable behaviors when the event occurs. courtesy of Mayer Johnson Routines are especially useful in supporting the development of functional skills. Activities related to independent living skills can easily be broken into individual steps and taught as routines. For example, creating a routine with visual supports for the toileting process helps minimize prompting and promotes independence. Many individuals with ASD have clearly established preferred items or activities. Building these skills into the routines supports the development of functional skills. Consider an individual who loves eating peanut butter sandwiches for lunch. Creating and teaching a routine with visual supports for accessing the necessary materials, making the sandwich, and cleaning up uses a highly motivating food item to develop the independent living skill of making a meal. It is important to consider that not even carefully developed routines are immune to change - a special event or illness can cause disruptions. Since individuals with ASD "function best when predictability is established across the school day" (Myles, Grossman, Aspy, Henry, & Bixler Coffin, 2007, p. 398-409), it is crucial to prepare for changes that may upset typical routines. Therefore, instruction related to routines should incorporate teaching the concept of flexibility and tolerance of change. Maintaining the structure of familiar routines while injecting preferred activities or objects can teach students that change can be positive and begin to increase the student's tolerance for unexpected events. Rules and Routines at Home Case Study: Anna Sheila struggled to find a support that could help Anna, her 14-year-old daughter with Asperger Syndrome, better manage her time after school. Sheila felt frustrated by the daily battle between homework and Anna's favorite computer activity. To keep the peace, Sheila gave in to Anna's daily demand for computer time, but homework suffered as a result. Sheila felt it was important to implement a set of rules as well as a routine for Anna to follow after school. Shelia identified one rule, "finish your homework before using the computer," to initially implement after school, then started to think about the routine. Recognizing that Anna did her best work after a short break and a snack, Sheila made this the first step in the after-school routine. Second was "take backpack to the office," followed by "complete homework," "have homework checked by an adult," then "put completed homework in backpack." "Computer time" completed the routine. Sheila decided the best presentation would be to have the steps written out and paired with boxes to be checked off as the individual steps were completed. She posted the routine on the bulletin board by the door where Anna could access it when she entered the house after school. Sheila reviewed and practiced the rule and routine with Anna for a few days, gradually fading her support as she saw Anna becoming more proficient. Anna learned to follow the steps independently and significantly increased the amount of homework she completed each day. The image to the right shows the visual supports Sheila used to teach Anna the new routine. Rules and Routines at School Case Study: Joey Understanding that Joey, a kindergarten student with ASD, needed both visual supports and predictability throughout his day, his teachers created a picture schedule outlining his daily activities. His visual schedule quickly became very important to Joey, but it wasn't long before his teachers noticed another issue developing. Joey was so anxious to check his schedule each morning that he would enter the classroom at a run, drop his backpack and coat in the center of the room and go directly to his transition area to check his schedule. Recognizing that Joey had developed a routine that was not acceptable in their classroom, his teachers knew that they would need to create a more appropriate morning routine for Joey to follow. The teachers decided to develop a routine for arrival that included the steps Joey had to follow when he came into the classroom each day. Once they determined the steps they would address, they chose a picture symbol to represent each one and sequenced the symbols on a strip of cardboard. For the next week, an adult met Joey each day as he got off the bus and did a mini-lesson with him about his routine. After the lesson, the adult prompted Joey through they steps of the routine in the classroom. Within a few weeks of implementation of this routine, Joey's arrival in the classroom became much more controlled and he was able to independently follow the steps in his morning routine. The picture to the right depicts the visual supports used to implement Joey's new rules and routines at school. Rules and Routines in the Community Case Study: Jose' Jose, a 19-year-old individual with autism, enjoyed participating in a community bowling league. Jose's brother, Angelo, typically drove him to and from the bowling alley, but a change in his work schedule made that impossible. Mike, one of Jose's teammates, offered to give him a ride instead. However, the first day that Mike went to Jose's house to pick him up, Jose became very upset with the change and refused to get in the car, repeatedly insisting that it was bowling day and he needed to go bowling. No level of explanation could convince Jose that just like Angelo, Mike would take him to the bowling alley. Mike and Angelo realized they needed to help Jose better understand the change in his routine. Knowing that Jose had responded well to video self-modeling in the past, they decided to develop a video to teach the new routine. From the backseat, Angelo filmed Jose getting into Mike's car, the two of them driving to the bowling alley, and going into the bowling alley together. Angelo then arranged for Jose to watch the video each day before Mike picked him up to bowl. Watching the video helped Jose understand the change and learn the new routine for his outings. Because Jose's family presented the change in a way he could comprehend (visually), his anxiety and fear significantly decreased. Soon after, Jose was able to enjoy bowling as in the past. Summary The predictability of clearly defined rules and routines promotes understanding and participation. Specifically, individuals with ASD may rely on rules and routines to reduce confusion, to make predictions about an event, and then to meet the expectations of the environment. Rules and routines are not the same. Each is a different strategy for establishing behavioral boundaries and expectations. Rules are statements defining behavior permissible in given situations or environments, whereas routines detail the steps required in carrying out certain actions. When designing rules for individuals with ASD it is important to determine what rules will be taught, ensure that the rules are concrete and comprehensible, determine how the rules will be taught and what structures and supports will facilitate understanding, and finally determine how the rules will be enforced. When designing routines for individuals with ASD, it is important to determine which activities or behaviors to target by teaching a routine, perform a task analysis of the routine, determine how to teach the routine and what structures and supports will support that instruction, and determine how inevitable changes in routine will be addressed. Post-Assessment Post-Assessment Rules and routines support individuals with ASD by addressing which of the following characteristics? Select an answer for question 612 Rules and routines are two different components of establishing behavioral boundaries and expectations. Select an answer for question 613 The structure and predictability of rules and routines allow individuals with ASD to manage information and meet the expectations of an environment. Select an answer for question 614 Rules should be: Select an answer for question 615 Routines can help support the development of functional skills. Select an answer for question 616 Rules and routines are more comprehensible when paired with visual supports. Select an answer for question 617 Discussion Questions [ Export PDF with Answers | Export PDF without Answers ] 1. Discuss the differences between rules and routines. Why are these distinctions important? A correct response would include: Rules are statements defining behavior permissible in given situations or environments, whereas routines detail the steps required in carrying out certain actions. Because rules and routines are often discussed together, it is important to distinguish between the two in order to ensure that both are being addressed. Establishing rules does not eliminate the need for routines and vice versa. 2. Discuss the connection between rules and routines. How do rules and routines support each other? A correct response would include: Each is a different strategy for establishing behavioral boundaries and expectations. After clearly defining rules for an individual with ASD it becomes easier to target the behaviors and routines that will facilitate compliance with the established rules. 3. Identify some rules and routines in your own life. Describe the structures that support these rules and routines. A correct response would include: For example, many individuals have waking up' routines. This might begin with an alarm going off, followed by a shower, dressing, drinking a coffee and having a bite to eat. Structures that facilitate completion of this routine may include setting the alarm to music rather than a beep, because one may find it more motivating to wake to music. Another example could be pre-preparing the coffee maker in the evening before going to bed. A rule associated with this routine may be that family members will wake one another if they are more than ten minutes late getting out of bed. 4. Why are rules and routines important for individuals with ASD? A correct response would include: The predictability of clearly defined rules and routines promotes understanding and participation. Specifically, individuals with ASD may rely on rules and routines to reduce confusion, to make predictions about an event, and then to meet the expectations of the environment. Citation and References If included in presentations or publications, credit should be given to the authors of this module. Please use the citation below to reference this content. Carnahan, C., & Snyder, K. (2011). Rules and routines: Online training module (Columbus, OH: OCALI). In Ohio Center for Autism and Low Incidence (OCALI), Autism Internet Modules, www.autisminternetmodules.org. Columbus, OH: OCALI. REFERENCES Carnahan, C., Hume, K., Clarke, L., & Borders, C. (2009). Using structured work to promote independence and engagement for students with autism spectrum disorders. Teaching Exceptional Children, 41(4), 6 - 14. Hodgdon, L. A. (2005). Solving behavior problems in autism: Improving communication with visual strategies. Troy, MI: QuirkRoberts Publishing. Hume, K., & Odom, S. (2007). Effects of an individual work system on the independent functioning of student with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 1166-1180. Mesibov, G. B., Shea, V., & Schopler, E. (2005). The TEACCH approach to autism spectrum disorders. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. Myles, B. S., Grossman, B. G., Aspy, R., Henry, S. A., & Bixler Coffin, A. (2007). Planning a comprehensive program for individuals with ASD spectrum disorders using evidence-based practices. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 42(4), 398-409. National Research Council (2001). Educating Children with Autism. Lord, C. & McGee, J.P. (Eds.), Washington, DC: National Academy Press. Reed, P. & Gibson, E. (2005). The effect of concurrent task load on stimulus overselectivity. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 35(5), 601-614. Schuler, A. L. (1995). Thinking in autism: Differences in learning and development. In K. A. Quill (Ed.), Teaching children with autism: Strategies to enhance communication and socialization (pp.11-32). New York: Delmar Publishers. Swanson, T. (2005). Provide structure for children with learning and behavioral problems. Intervention in School and Clinic, 40, 182-187. Tien, K. C., & Lee, H. J. (2007). Structure/modifications. In S. Henry & B. S. Myles (Eds.), The comprehensive autism planning system (CAPS) for individuals with Asperger Syndrome, autism, and related disabilities: Integrating best practice throughout the student's day (pp. 23-44). Shawnee Mission, KS: Autism Asperger Publishing Company.