Psychoanalysis in San Francisco: The History Begins

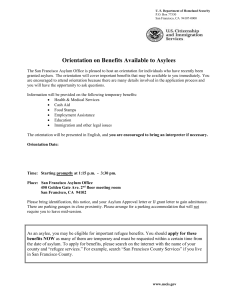

advertisement