Lizzio & Wilson First Year Student`s Appraisal of

First-Year Students’ Appraisal of Assessment Tasks: Implications for efficacy, engagement and performance.

Alf Lizzio and Keithia Wilson

Griffith University

Corresponding Author: Professor Alf Lizzio, Griffith Institute for Higher Education, Griffith

University, Queensland Australia. Email: a.lizzio@griffith.edu.au

Acknowledgement: This study was funded by a grant from the Australian Learning and

Teaching Council.

Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, Volume

38 , Issue 4 , 2013

1

Abstract

This study investigated students’ appraisals of assessment tasks and the impact of this on both their task-related efficacy and engagement and subsequent task performance.

Two hundred and fifty-seven first-year students rated their experience of an assessment task (essay, oral presentation, laboratory report or exam) that they had previously completed. First-year students evaluated these assessment tasks in terms of two general factors: the motivational value of the task and its manageability. Students’ evaluations were consistent across a range of characteristics and level of academic achievement.

Students’ evaluations of motivational value generally predict their engagement and their evaluations of task manageability generally predict their sense of task efficacy.

Engagement was a significant predictor of task performance (viz., actual mark) for exam and laboratory report tasks but not for essay-based tasks. Findings are discussed in terms of the implications for assessment design and management.

2

This study seeks to understand the factors that students’ use to appraise or evaluate an assessment task and the consequences of their perceptions for their subsequent motivation and performance. An evidence-based understanding of the processes that influence students’ engagement with assessment is particularly important for informing our educational practice with first-year or commencing students who are relatively unfamiliar with the culture and context of university-level assessment.

While the way in which students approach learning may, to some extent, be a function of their personal disposition or abilities, the nature of the learning task itself and the environment in which it is undertaken also significantly mediate their learning strategy (Fox,

Mc Manus, & Winder, 2001). More accurately, it is students’ perceptions, rather than any objective features of tasks, that are crucial in shaping the depth of their engagement. In this sense, students’ learning approaches (process factors) and academic performance (product factors) are influenced by their appraisal of, and interaction with, the curriculum content, design and culture of their current ‘learning system’(presage factors) (Biggs, 2003). Central to this process is a significant body of research indicating students’ perceptions of the methods, modes and quantity of assessment to be perhaps one of the most important influences on their approaches to learning (Entwistle & Entwistle, 1991; Trigwell & Prosser,

1991; Ramsden, 1992; Lizzio, Wilson & Simons, 2002). Indeed it has been argued that students’ perceptions of assessment tasks ‘frame the curriculum’ and are more influential than any intended design elements (Entwistle, 1991), to the extent of potentially overpowering other features of the learning environment (Boud, 1990).

The appreciation that assessment functions not only to grade students, but also fundamentally to facilitate their learning, is central to the paradigm evolution from a traditional summative ‘testing culture’ to an integrated ‘assessment culture’ (Birenbaum,

1997). Understanding how students appraise or construct their learning is the foundation of

3

design frameworks such as integrated teaching (Wehlburg, 2010) and constructive alignment

(Biggs, 1996a) which view students’ engagement and performance with assessment as a complex interaction between learner, task and context. From this perspective, the consequential validity of an assessment task or mode (viz., its positive influence on students’ learning approaches and outcomes) is a key consideration (Dierick & Dochy, 2001). The importance of students perceiving course objectives and pedagogy to be congruent, besides satisfying the test of ‘common-sense’, has also received empirical support. For example, a curriculum that emphasises acquisition of knowledge and a concurrent assessment package that emphasises problem solving (Segers, Dierick, & Dochy, 2001) has been found to contribute to both sub-optimal learning and student resentment. The implications of these findings for educational practice are quite fundamental. A foundational educational discipline would appear to be the need to distinguish between our educational intentions (however worthy) and their impact on students. This requires us to more closely examine the ‘hidden curriculum’ (Snyder, 1971) of our assessment practices. If we want to understand and evaluate our learning environments we need to authentically understand how students experience them. Thus, if our aspirations are to influence students towards deeper learning and higher-order skill development then a prerequisite task is to appreciate students’ perceptions of the assessment tasks with which we ask them to engage.

Students’ Perceptions of Assessment

Students’ preferences for different modes of assessment (Birenbaum 2007) and the effects of different assessment methods (e.g., multiple choice formats, essays) on whether students’ adopt deep or surface approaches to study (Scouller, 1997; Trigwell & Prosser, 1991;

Thompson & Falchinov, 1998) have been well-established. It is interesting to note that while there may be clear differences in the ways that students with different study strategies approach assessment, there are also significant commonalities in their criticisms of the

4

processes of some traditional assessment practices (Lindblom-Ylanne & Lonka, 2001). A series of qualitative studies have investigated students’ perceptions of the assessment characteristics that they report as positively influencing their learning and engagement. Mc

Dowell (1995) found that perceived fairness was particularly salient to students’ perceptions of both the substantive validity and procedural aspects of an assessment task. Sambell, Mc

Dowell and Brown (1997) extended this early work and identified the educational values

(authentic tasks, perceived to have long term benefits, applying knowledge), educational processes (reasonable demands, encourages independence by making expectations clear), and the consequences (rewards breadth and depth in learning, rewards effort) of assessment that influence students’ perceptions of its validity. More recently, Savin-Baden (2004) examined students’ experience of assessment in problem-based learning programs and identified two meta themes in students’ comments, and conceptualised these as forms of student disempowerment: unrewarded learning (including the relationship between the quantity of work and its percentage weighting), and disabling assessment mechanisms, including both processes (e.g., lack of information and inadequate feedback) and forms (assessment methods that didn’t fit with espoused forms of learning). Further empirical support for the centrality of notions of empowerment and fairness to students comes from studies of social justice processes in education. For example, Lizzio, Wilson and Hadaway, (2007) found students’ perceptions of the fairness of their learning environments were strongly influenced by the extent to which they both feel personally respected by academic staff and the adequacy of the informational and support systems provided for them to ‘do their job’, of which assessment was a core component.

What these investigations share is an appreciation of the value of a situated and systemic investigation into the student experience. The focal question is not just ‘what type of assessment’ but ‘what type of assessment system’ are students experiencing on both cognitive

5

and affective levels. Thus, there is a balanced concern with the impact of both assessment content and assessment process (Gielen, Dochy & Dierickl, 2003) on student learning and satisfaction. Hounsell, Mc Cune, and Hounsell (2008) have extended this guiding notion of

‘assessment context’ by operationalising the prototypical stages of an assessment lifecycle and identifying students’ needs and concerns as they engage with, and seek to perform, assessment tasks (viz., their prior experiences with similar assessment, their understanding of preliminary guidance, their need for ongoing clarification, feedback, supplementary support and feed-forward to subsequent tasks). Hounsell et al., in particular demonstrated that the perceived adequacy of guidance and feedback as students attempted tasks were central to their success. Lizzio and Wilson (2010) utilised Hounsell et als'., (2008) framework to investigate first-year students’ appraisal of a range of assessment tasks using focus groups and individual interviews. These students evaluated their early university assessment tasks in terms of seven dimensions (familiarity with type of assessment, type and level of demand/required effort, academic stakes, level of interest or motivation, felt capacity or capability to perform the task, perceived fairness and the level of available support). The dimensions identified in this study confirm a number of the themes (e.g., demand, motivation, fairness, and support) commonly identified in previous investigations of student perceptions of assessment.

Parallel to this line of inquiry has been the development of a number of good practice frameworks to guide the design of assessment protocols. For example, Gibbs and Simpson

(2004) identified eleven conditions under which assessment supports students’ learning, and developed the Assessment Experience Questionnaire (AEQ) as a measure of the extent to which these conditions (viz., good distribution of time demands and student effort, engagement in learning, appropriateness of feedback, students’ use of feedback) were evident in a particular learning context. More recently, Boud and associates (2010) developed a set of

6

seven propositions for assessment reform in higher education. The propositions address the centrality of assessment to the learning process (assessment for learning placed at the centre of subject and program design) and both questions of academic standards (need for assessment to be an inclusive and trustworthy representation of student achievement) and the cultural (students are inducted into the assessment practices and cultures of higher education) and relational (students and teachers become responsible partners in learning and assessment) dimensions of assessment practice that can serve to help or hinder student engagement and learning. The conceptualisation of ‘assessment systems’ and the empirical validation of underlying assumptions from a student’s perspective is a useful basis for guiding change processes in higher education. Thus, for example, Gibbs and Simpson’s framework has been employed to provide the evidence-base in collaborative action research projects to improve assessment practices (Mc Dowell, et al., 2008). Similarly, Carless (2007) reports the use of a learning–oriented assessment framework to inform action learning at both the institutional and course level.

Broader Research Traditions

What can we learn about good assessment practice from broader research traditions? There is considerable convergent support from studies of psychological needs, cognitive load and wellbeing, for the importance of both appreciating students’ key role in constructing the meaning or ‘making sense’ of their experiences with assessment and actively incorporating this into design and management processes.

Students’ psychological needs may be particularly influential on their approach to assessment tasks. Cognitive evaluation theory proposes that people appraise events in terms of the extent to which their needs to feel competent and in control will be met (Deci & Ryan,

2002). From this perspective, events or tasks that positively influence student’s perceived

7

sense of competence will enhance their motivation. Legault, Green-Demers, & Pelletier

(2006) identified four dimensions of academic motivation (student’s ability and effort beliefs, characteristics of the task and value placed on the task) and found that in a particular context these may interact to produce either high levels of motivation or feelings of general helplessness. Clearly, a student’s appraisal of an assessment task and what it may demand/require from them in terms of effort and ability appear to be important considerations in how they will both engage (or detach) and approach its performance. This of course raises the question: What are the characteristics of assessment design that optimally support a students’ sense of competence and autonomy? Certainly, how the assessment process is managed may be salient to student’s efficacy and approach, as constructive task-related interpersonal support has been found to encourage self-determined motivation (Hardre &

Reeve, 2003). Given that students look to information provided from both the task and their teachers to affirm their academic capability, appropriately matching task demands to student capabilities may be a key design consideration.

Cognitive load theory also provides insights into the processes that are salient to students’ experience of assessment tasks, in terms of both their efficiency and effectiveness, and their appropriateness to learners’ levels of expertise. From this perspective, it is not just students’ performance outcome on an assessment (viz., their grade) that is of interest, but also the degree of cognitive effort required. Students’ cognitive load typically derives from two sources, the intrinsic load of a learning task (usually the level of interactivity or complexity of its constituent elements) and any extraneous load placed on the student as a result of its management (e.g., poor timing and clarity of scaffolding information to learners and mismatched instructional procedures) (Kalyuga, 2011). Importantly, since load is additive, assessment tasks with higher intrinsic load are more likely to be negatively affected by process factors which increase extraneous load (Pass, Renkl & Sweller, 2003). The question

8

of ‘managing cognitive load’ may be particularly important for novice learners who lack the working schemas to integrate new knowledge. Tasks that require students to find or construct essential information for themselves (unguided or minimal guidance) have been found to result in less direct learning and knowledge transfer compared to tasks where scaffolded guidance is provided (Kirschner, Sweller & Clark, 2006).

The goal of protecting or enhancing student well-being may also be relevant to our management of the assessment process. University students generally report lower levels of well-being than the general population, with first-year being a time of heightened anxiety

(Cooke, Bewick, Barkham, Bradley & Audin, 2006). Given the identified vulnerabilities of this population, there may be a significant ethical and mental health dimensions to good assessment practice. Work stress and well-being can be influenced by the psychosocial system within which a person functions and effective person-system interaction is commonly conceptualised as the necessary balance of the factors of reasonable job or task demand, necessary support and opportunities for control and positive working environment (Kanji &

Chopra, 2009). Whether high demands result in positive activation or strain will depend on the presence of appropriate support and felt control (Barnes & Van Dyne, 2009; Karasek,

1979). These findings can be readily generalised to the leadership of learning environments, with implications for both the design of assessment tasks and the support of students through the performance process.

First-Year Students

The present study is particularly concerned with the experience of first-year or commencing students’ experiences of assessment. Early academic experiences have been identified as critical to the formation of tentative learner identities and self-efficacy (Christie, et al., 2008). Clearly, ‘assessment backwash’ (Biggs, 1996), whereby badly designed or

9

poorly organised assessment can unintentionally impair students’ learning, is more likely with a commencing student population. Indeed poorly matched and managed assessment is arguably a major contributor to the phenomenon of premature ‘student burnout’ (viz., feelings of exhaustion and incompetence and a sense of cynicism and detachment) (Schaufeli, et al., 2002) and disengagement. From a positive perspective, first-year learning environments potentially provide our greatest opportunities to not only align our educational intentions and impact, but also, to work collaboratively with new students to develop an evidence-based culture of success. An empirically supported understanding of the design and process elements of our ‘assessment systems’ can potentially make a contribution to the important challenges of student engagement and retention.

However, it should be noted that a wholistic approach to assessment that actively engages with students’ needs and expectations is a somewhat contested proposition. On the one hand arguments are made for greater accommodation and inclusion of students’ voices and circumstances around assessment. In Birenbaum’s (2007) terms this requires moving away from an ‘inside out’ approach where the ‘insiders’ (teachers) assume ‘what’ and ‘how’ needs to be assessed, to a greater engagement with an ‘outside in ‘ approach where students’ preferences are legitimated. On the other hand there is an increasing concern with the apparent rise within the student population of notions of ‘academic entitlement’

(Greenberger, et al., 2008), and an invocation to academics not to collude with or accommodate ‘student demands’. The present paper takes the position that, with first-year students in particular, pejorative labels of ‘demanding and entitled students’ do little to advance practice, and that from a systems perspective, such behaviour may also be understood as ‘students trying to assertively negotiate with institutions which may be perceived as somewhat indifferent to their success or wellbeing. In this sense the genesis of this observed behaviour may be more interactive than individual.

10

Aims

The present study aims to contribute to our understanding of the aspects of assessment that influence first-year students’ engagement, confidence and learning outcomes. Research to date has identified a number of design and process factors that may be particularly salient to students; however, there is a need for the structure of these to be more clearly identified and their relative impact on first-year students’ efficacy and performance assessed.

Thus the focal research questions for the present study are:

What are the general dimensions which first-year students use to appraise or evaluate assessment tasks?

How do first-year students’ appraisals influence their sense of efficacy and approach to assessment tasks?

What is the contribution of first-year students’ appraisals and approaches to their actual performance on assessment tasks?

What are the implications of these insights for the design and management of assessment?

Method

Participants

Two hundred and fifty seven first-year students (212 females and 45 males) across four disciplinary programs (Medical Science (16), Nursing (65), Psychology (81) and Public

Health (38)) participated in this study. The mean age of the sample was 25 years (SD =

9.1years) and 56% were the first in their family to attend university. Students were in their second semester of university study and their mean grade point average (GPA) on their first semester courses was 5.5 on a 7-point scale.

11

Procedure

Students were emailed at the beginning of their second semester of study and invited to participate in an online survey. Approximately 35% of the targeted student population responded to the invitation. The survey process asked students to “”Reflect back on your first semester of university study and to recapture the experience of ‘being new to it all’. Recall your early thoughts and feelings about the assessment tasks you had to complete”. Students were then asked to select one type of assessment task (exam, oral presentation, essay or laboratory report) and to use the scales provided to “honestly tell us how you remember thinking and feeling as you approached this task”. Some students (n = 87) completed the survey for more than one assessment task. In the first section of the survey students rated their selected assessment task on a set of 28 items operationalising each of the seven dimensions (viz., familiarity with type of assessment, type and level of demand/required effort, academic stakes, level of interest or motivation, felt capacity or capability to perform the task, perceived fairness and the level of available support) identified by first-year students as how they appraise or evaluate assessment in Lizzio and Wilsons’ (2010) qualitative study.

Items were piloted with a small group of students (n= 12) to establish clarity of wording and appropriate matching of items to dimensions. In the second section of the survey students evaluated their response to the assessment task in terms of their self-reported levels of taskrelated confidence ( I am confident that I will do well on this assessment task) , anxiety (

I’m feeling fairly anxious about this assessment task ), achievement motivation ( I want to do very well on this assessment task ) and approach to learning on the task ( I will be approaching this task with the aim of learning as much as possible ). Students were also asked to report their level of academic performance (percentage mark) on their selected assessment task. Finally, students provided demographic (age, gender), background (equity group membership, prior

12

family participation in higher education) and academic (university entrance score, GPA for their first semester courses) information.

Results

A series of analyses were conducted. Firstly, exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses were used to investigate the structure of first-year students’ appraisals of assessment tasks.

Secondly, correlation analyses were used to establish if students’ appraisal processes were associated with a range of demographic, background or academic achievement factors.

Finally, structural equation modelling was used to establish the relationships between students’ appraisal processes, their approach to assessment tasks and their performance on those tasks.

Structure of students’ appraisal of assessment

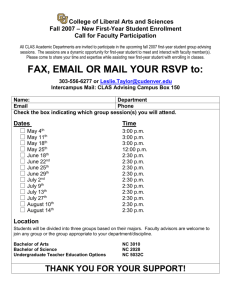

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy indicated the data set was highly structured and appropriate for further factor analysis (KMO = 0.94). Students’ responses to the 28 items describing their appraisal of the four assessment tasks (exam, oral presentation, essay and laboratory report) were analysed using exploratory factor analysis

(Principal Axis Factor analysis (PAF) with varimax rotation). This initial analysis yielded a two-factor solution accounting for 79.36% of the variance, with 17 items loading on factor 1

(72.19% variance, Eigenvalue 20.21) and 6 items on factor 2 (7.17% variance, Eigenvalue

2.0). Cross-loading, low loading and highly correlated items were removed, and a PAF analysis was then conducted on the reduced 15 item set. This analysis produced an interpretable two-factor solution with simple structure accounting for 81.64% of variance with 8 items loading on factor 1 (variance 42.43%) and 7 items on factor 2 (variance 39.21%)

(See Table 1).

13

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Insert Table 1 about here

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The first factor was defined by four themes related to first-year students’ perceptions of the motivational content and value of an assessment task: the perceived academic stakes of the task (How important is it to do this well?), its level of intellectual challenge (What will it take me to do this?), the motivational value of the task (Do I want to do this?), and students’ sense of task capability (Can I do this?). The academic stakes of the assessment task were pragmatically reflected in students’ instrumental perceptions of potential contribution to their grades ( The weighting of this task is sufficiently high for me to be concerned about how it will impact on my overall grade). The intellectual challenge of an assessment task was reflected in terms of perceived cognitive load ( This assessment task requires us to learn a lot of material), and intellectual demands ( This assessment task requires us to really think about the material ; This assessment task requires me to demonstrate mastery of skills ).The motivational value of an assessment task was reflected in terms of items related to clarity of learning outcomes ( I can see how doing this assessment task will develop my academic skills ) and curriculum alignment ( This assessment task makes sense to me given the learning objectives of this course ). First-year students’ sense of capability to undertake the assessment task was also expressed in terms of prior familiarity ( I have recently done something similar to this task ) and confidence ( I have the skills required to do this assessment task ).

The second factor contained four themes related to students’ perceptions of the m anageability of an assessment task: fairness (How fair is this task?), support (Who can help with this task?), self-protection (How safe is this task?) and self-determination (Is this in my hands?). The fairness aspects were reflected in students’ perceptions of the required difficulty

( I think this assessment task is at an appropriate level for first-year students ), required

14

investment ( I think the weighting of this assessment task matches the time required to do it ) and level of organisation ( I feel that this assessment task is organised fairly ). Students’ sense of appropriate support with an assessment task was expressed through the perceived availability of staff ( My sense is that there will be good mechanisms in place to support students with this assessment task ), and workload management ( I have a good sense of the workload involved in this task ). Students also associated items related to ego threat and shame ( It’s fairly safe to ‘have a go’ with this assessment task without a high risk of ‘looking stupid’ or making a mistake

) and a sense of personal control ( This assessment task allows individual students sufficient personal control over how well they will perform ) on this factor.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was then used to test the fit of the data to either a single or two-factor model. Unlike exploratory factor analysis which provides only an indirect test of a theoretical model, CFA provides a direct test of the proposed models

(Bernstein & Teng 1989). Given the high level of inter-factor correlation (0.85) the first analysis tested whether all items could be associated with a global assessment appraisal factor. However this yielded a very poor fit with none of the indices meeting accepted standards. A two-factor conceptualisation of students’ appraisal of assessment was then tested and after removal of co-varying items yielded a good level of fit of the model to data

(

Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) =.97, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = .98,

Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) = .97, Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI) = .94, Root Mean

Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) =.06). A good fit is generally indicated by measures of incremental fit (closer to 1 is better, with values in excess of 0.9 recommended) and measures of residual variance (RMSEA recommended to be not higher than 0.08) (Hu &

Bentler, 1999). The reduced first-factor was defined by three items concerned with the perceived motivational content and value of an assessment task: learning outcomes (.70) ( I can see how doing this assessment task will develop my academic skills ), curriculum

15

alignment (.74) ( This assessment task makes sense to me given the learning objectives of this course ) and intellectual demand (.35) ( This assessment task requires me to demonstrate mastery of skills ).The reduced second factor was defined by four items concerned with the perceived manageability of an assessment task: fairness of required investment (.81) ( I think the weighting of this assessment task matches the time required to do it ), appropriate difficulty (.89) ( I think this assessment task is at an appropriate level for first-year students ), transparency of workload (.77) ( I have a good sense of what workload is involved in this task ) and appropriate support (.41) ( My sense is that there will be good mechanisms in place to support students with this assessment task ). Inter-factor correlation was reduced to .68 indicating that the confirmatory analysis had better differentiated these two assessment appraisal dimensions.

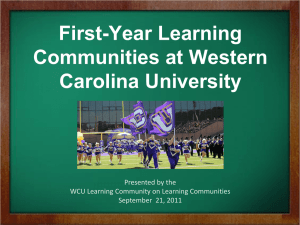

Relationship of appraisal factors with student characteristics

Correlations were conducted to examine the associations between student characteristics and the appraisal dimensions (See Table 2). Students’ appraisals of assessment tasks were not significantly associated with demographic (age, gender), background (first-generation status, equity group membership, English as second language) or level of academic achievement

(tertiary entrance score or first-semester GPA). This suggests that students’ perceptions of assessment tasks were not significantly confounded by variations in their characteristics or circumstances. While this pattern of findings does not necessarily establish the validity of students’ evaluations, it does increase our confidence in their consistency or consensus.

Results suggested that students’ appraisals of assessment were significantly associated with their task-related confidence, anxiety and task orientation. This indicated the value of further analyses of the contribution of these variables to assessment performance.

16

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Insert Table 2 about here

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

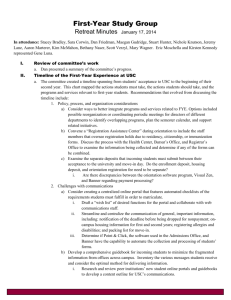

General relationship of students’ appraisals to assessment approach and performance

Structural Equation modelling (SEM) analyses (using the AMOS program) were conducted to test the contribution of students’ appraisals of assessment tasks to their approaches and their actual outcomes on a task. This allowed examination of direct and indirect relationships between variables and the extent to which a conceptual model adequately fitted the empirical data. The first analysis tested the global relationship, across all assessment types, of students’ scores on the two appraisal factors (perceived assessment motivational content and value and perceived assessment manageability) to their reported approach to the task. Students’ ratings of their levels of confidence and anxiety on an assessment task formed the latent variable assessment task efficacy and students’ ratings of their levels of achievement motivation and deep learning orientation to the assessment task formed the latent variable assessment task engagement, which is conceptually similar to the construct of a deep-achieving approach to learning (Donnon & Violato, 2003; Fox, et al., 2001). This analysis produced a moderate model fit (

2

(39) = 117.244, p < .0001;

2

/df ratio = 3.04; TLI = .86; CFI = .90; GFI = .91,

AGFI = .85, RMSEA = .10) with theoretically interpretable associations between variables.

See Figure 1 for a simplified presentation of the model.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Insert Figure 1 about here

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Students’ perceptions of the motivational content and value of assessment tasks significantly positively predicted their level of task engagement. Students appear to be describing a pattern of engagement whereby ‘good academic behaviour’ (viz., wanting to

17

learn and do well) is facilitated when they experience an assessment task to be aligned with broader learning objectives, be appropriately challenging and to be of value to them.

Students’ perceptions of the manageability of assessment (viz., its fairness and level of support) significantly positively predicted their sense of task efficacy. In this regard, students are making a clear association between perceived task processes (viz., the more clear, fair, supported, and in-control we feel) and their sense of task-related efficacy. This is certainly consistent with previous findings whereby constructive task-related interpersonal support encouraged self-determined motivation (Hardre & Reeve, 2003).

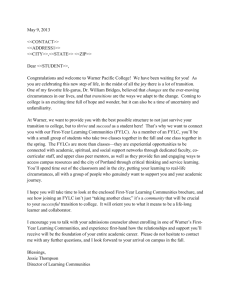

General relationship of students’ appraisals with specific assessment tasks

While the above analysis provides a level of insight as to the ‘general conceptual model’, it is also important to understand how these processes function with specific types of assessment tasks. Separate analyses were conducted to test relationships between first-year students’ perceptions and approaches and assessment outcomes for four sub-sets of the overall sample: essay, oral presentation, laboratory report and closed-book exam tasks.

Students’ reported marks on each task were converted to a standard percentage value to form the dependent variable assessment outcome .

These analyses must be considered exploratory given that, because of smaller sample sizes

(exam n = 137; laboratory report n = 85; essay n = 122; oral presentation n = 85), they do not satisfy the recommended ratio of participants to parameters for a latent variable analysis

(Bentler & Chou, 1987). Thus, while the SEM analyses for each of these tasks produced interpretable models, because of limited sample sizes, the levels of fit were relatively modest

(Exam CFI = .87, RMSEA = .10; Essay CFI = .87, RMSEA =.12; Oral presentation CFI =

.83, RMSEA = 1.22; Laboratory report CFI = .86, RMSEA = .10). However, given the

18

exploratory nature of the present study, these findings are cautiously reported for theory development purposes (See Figure 2).

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Insert Figure 2 about here

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

While the previous overall analysis across all assessment tasks produced clear general associations, these task-specific analyses suggest that students’ appraisals of motivational value and manageability will have different impacts on their task-related engagement and efficacy depending on the type of task being undertaken. Exam-based tasks appeared to function in the most straightforward fashion for students. Thus, the greater the perceived motivational value of an exam the greater students’ task engagement, which, in turn, contributed to a better assessment outcome. Students’ relative familiarity with the examination format may also explain why their perceptions of support do not predict their level of task efficacy. Consistently, given that performance based tasks such as oral presentation involve a level of anxiety and public evaluation, it should not be surprising that perceived manageability influenced students’ sense of efficacy more than the structured

(laboratory report), and traditionally private (examination) forms of assessment.

However, first-year students reported a different pattern of associations with their experience of essay-based tasks. Students’ perceptions of manageability of an essay task were a strong positive predictor of both their essay writing efficacy and their engagement with the task. What might be different about commencing students’ perceptions of essay tasks that would, unlike other assessment tasks they undertook, result in perceived support influencing both their efficacy and engagement?

19

It may be that essay-based tasks are particularly problematic for first-year students. As

Hounsell’s (1984) seminal work demonstrated, students (particularly commencing students) have varied and often contradictory conceptions of academic essay writing, and in addition, there is considerable cross-disciplinary variability in the opportunities to systematically develop this capability. McCune (2004), following a longitudinal study of first-year psychology students’ learning, similarly concluded that students have considerable difficulty in developing their conceptions of essay writing and understanding expected disciplinary discourses. Beyond this, the guidance provided by tutors was often ‘tacit and sophisticated’, and thus less accessible to students than staff might expect. Assessment tasks such as exams and laboratory reports have a comparatively clearer logic and explicit structure than essay writing in its many potential forms. Thus, in this regard, university-level essays are ‘new territory’ with ‘hard to learn’ rules’. Students in these circumstances may be pejoratively labelled as ‘anxious and dependent’ (and indeed they themselves report more anxiety), but from a system’s perspective they are simply seeking to negotiate tasks that are perhaps significantly more challenging and inherently ambiguous than insiders ‘comfortably in the discourse’ may expect or intend. Unfortunately, unlike other more familiar (e.g., exams) or structured (e.g., laboratory reports) assessment tasks, students’ best intentions and efforts

(viz., higher task engagement) were not routinely reflected in higher grades. First-year students, in the present sample at least, were perhaps yet to sufficiently develop the enabling conceptions and strategies that mediate or bridge engagement (their intentions) and performance (their outcomes).

Interestingly, only students’ reported level of task engagement ( I will be approaching this task with the aim of learning as much as possible; I want to do very well on this assessment task) was a significant positive predictor of their actual performance on an assessment task

(viz., their marks). Thus clearly, outcomes may be less a function of how students feel

20

(anxiety, confidence) and more what they actively seek to do (learn and achieve) in relation to a task. The present analysis provided little support for previous findings that position selfefficacy as a strong predictor of success (Gore, 2006). Present findings are consistent with research demonstrating that constructs such as self-efficacy are less influential of performance as tasks become more complex (Chen, Casper, & Cortina, 2001), and that selfefficacy expectations are less accurate in field settings (Stajkovic & Luthans, 1998). It may be that first-year students are not well-equipped to make accurate appraisals of their abilities in relatively unfamiliar learning contexts. Indeed, student over-optimism has been identified as a significant contributor to academic failure in the first year of university (Haynes, et al.,

2006).

The stronger contribution of students’ perceptions of assessment task value to their task performance should not be taken to indicate that we can discount the importance of effectively responding to students’ need for guidance and support through the assessment lifecycle. Firstly, from a cognitive load perspective while the structure of an assessment task establishes the intrinsic load of a task, an appropriate assessment management process reduces extraneous load on students. Secondly, both cognitive and affective processes are important to student satisfaction and well-being. Thus, for example, while students may be able to ‘do well’ with a challenging task they may also ‘become unnecessarily stressed’ in the process. Designing challenging and engaging assessment tasks and implementing these within a fair and supportive context is likely to enhance students’ satisfaction as well their achievement. This is particularly the case since variables strongly defining students’ evaluation of assessment process (e.g., fairness) have been shown to influence higher order affective outcomes such as identification and belonging (Lizzio, et al., 2007).

Implications for Practice

21

Present findings provide some guidance as to the elements that first-year students use to appraise their assessment tasks. In terms of assessment task design, students are particularly sensitive to a task’s motivational potential. In terms of assessment task process, students are particularly aware of the perceived manageability of a task (as judged by appropriate weighting, organisation and support). Given that students’ perceptions of task motivational value and manageability both contribute to their sense of efficacy and engagement in different ways, optimal learning is more likely to be achieved if assessment is not so much

‘set for students’ as ‘discussed with them’. This may have a twofold benefit: firstly, establishing a clear and explicit assessment system, and secondly, cueing students to the implicit processes that may be influencing their engagement. In this sense, staff-student dialogue contributes to the higher-order goal of enabling students to more effectively selfregulate with unfamiliar or challenging tasks.

Future Research

There are a number of limitations with the present study that require consideration and should be addressed in future research. The present study was retrospective in design, with students reporting their ‘remembered perceptions’, which may raise questions of accuracy of recall.

Future research should seek to address these questions by prospectively monitoring students’ progress through the assessment lifecycle from the point of first contact onwards. A second limitation of the retrospective nature of this study concerns the composition of the student sample. Failed and non-retained students are underrepresented in the present sample and thus present findings may have limited generalisability to students with at-risk characteristics.

Only modest levels of fit were obtained due to restricted sample sizes for the separate analyses of each type of assessment. Clearly, present findings should be replicated with larger and more diverse student populations. The variability in the pattern of associations across assessment types (particularly essay tasks) strongly indicates that analyses should be

22

conducted at the task specific level and only cautiously aggregated to a general model. In this regard, students’ appraisals of diverse assessment tasks (e.g., group work) should also be investigated to determine the general applicability of present findings. Finally, consideration should be given to investigating the extent to which individual difference variables may mediate the relationships between students’ appraisal of assessment tasks and their subsequent engagement and performance. For example, the extent to which students actively deconstruct both the tacit and explicit expectations or cues of assessment (viz., the extent to which they are strategic cue-seekers, cue-conscious or cue deaf/oblivious) (Miller & Parlett,

1974), may be particularly influential. Similarly, students’ dispositional approaches to learning should be measured to determine the differential contribution of general presage factors and appraisals of specific assessment tasks to their subsequent engagement and performance.

23

References

Barnes, C. M. & Van Dyne, L. (2009). “I’m tired: Differential effects of physical and emotional fatigue on workload management strategies. Human Relations, 62, 59-92.

Bentler, P. M., & Chou, C. P. (1987). Practical issues in structural equation modelling.

Sociological Methods and Research , 16 , 78-117.

Bernstein, I. H., & Teng, G. (1989). Factoring items and factoring scales are different:

Spurious evidence for multidimensionality due to item categorization. Psychological Bulletin,

105, 467-477.

Biggs, J. B. (2003). Teaching for quality learning at university.

Buckingham: Open

University Press.

Biggs, J. B. (1996a). Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. Higher Education,

32, 347-364.

Biggs, J. B. (1996b). Assessing learning quality: reconciling institutional, staff and educational demands. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 21, 5-15.

Birenbaum, M. (2007). Assessment and instruction preferences and their relationship with test anxiety and learning strategies. Higher Education, 53 , 749-768.

Birenbaum, M. (2003). New insights into learning and teaching and the implications for assessment. In M. Segers, F. Dochy, & E. Cascallar (Eds.), Optimising new modes of assessment: In search of qualities and standards.

Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Birenbaum, M. (1997).Assessment preferences and their relationship to learning strategies and orientations. Higher Education, 33, 71-84.

Boud, D. and Associates (2010). Assessment 2020: Seven propositions for assessment reform in higher education.

Sydney, Australian Learning and Teaching Council.

Boud, D. (1990). Assessment and the promotion of academic values. Studies in Higher

Education, 15, 101-111.

Carless, D. (2007). Learning-oriented assessment: conceptual bases and practical implications. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 44, 57-66.

Chen, G., Casper, W.J., & Cortina, J.M. (2001). The roles of self-efficacy and task complexity in the relationships among cognitive ability, conscientiousness, and work-related performance: A meta-analytic examination. Human Performance, 14, 209-230.

Christie, H., Tett, L., Cree, V. E., Hounsell, J. & McCune, V. (2008). ‘A real rollercoaster of confidence and emotions’: learning to be a university student.

Studies in Higher Education,

33, 567-581.

24

Cooke, R., Bewick, B. M., Barkham, M., Bradley, M., & Audin, K. (2006). Measuring, monitoring and managing the psychological well-being of first-year university students.

British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 34, 505-517.

Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. (2002). Overview of self-determination theory: An organismic dialectical perspective. In E. L. Deci & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination research (pp. 3-33), Rochester, New York: University of Rochester Press.

Dierick,S. & Dochy, F. (2001). New lines in edumetrics: new forms of assessment lead to new assessment criteria. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 27, 307-329.

Donnon, T. & Violato, C. (2003). Testing competing structural models of approaches to learning in a sample of undergraduate students: A confirmatory factor analysis. Canadian

Journal of School Psychology, 18 , 11-22.

Entwistle, N. J. (1991). Approaches to learning and perceptions of the learning environment.

Higher Education, 22, 201-204

Entwistle, N. J. & Entwistle, A. (1991). Contrasting form of understanding for degree examinations: The student experience and its implications. Higher Education, 22, 205-227.

Fox, R. A., Mc Manus, I.C., & Winder, B.C. (2001). The shortened Study Process

Questionnaire: An investigation of its structure and longitudinal stability using confirmatory factor analysis. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 71, 511-530.

Gibbs, G., & Simpson, C. (2004). Does your assessment support your students’ learning?

Journal of Learning and Teaching in Higher Education, 1, 3-31.

Gielen, S., Dochy, F. & Dierick, S. (2003). Evaluating the consequential validity of new modes of assessment: The influence of assessment on learning, including pre, post and true assessment effects. In M. Segers, F.Dochy, & E. Cascallar (Eds.). Optimising for new modes of assessment: In search of qualities and standards (pp.37-54). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic

Publishers.

Gore, P.A. (2006). Academic self-efficacy as a predictor of college outcomes: Two incremental validity studies. Journal of Career Assessment, 14, 92-115.

Greenberger, E., Lessard, J., Chen, C., & Farruggia, S. P. (2008). Self-entitled college students: Contributions of personality, parenting and motivational factors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37, 1193-1204.

Hardre, P. L. & Reeve, J. (2003). A motivational model of rural students’ intentions to persist in, verses drop out of high school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95, 347-356.

Haynes, T. L., Ruthig, J. C., Perry, R. P., Stupnisky, R. H., & Hall, N. C. (2006). Reducing the academic risks of over-optimism: The longnitudinal effects of attribution retraining on cognition and achievement. Research in Higher Education, 47 ,755-779.

25

Hounsell, D. (1984). Essay planning and essay writing. Higher Education Research and

Development. 3 , 13-31.

Hounsell, D., Mc Cune, V., & Hounsell, J. (2008). The quality of guidance and feedback to students. Higher Education Research and Development. 27 , 55-67.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P.M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indicies in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria verses new alternatives. Structural Equation Modelling, 6 , 1-

55.

Kalyuga, S. (2011). Cognitive load theory: How many types of load does it really need?

Educational Psychology Review, 23 , 1-19.

Kanji, G. K. & Chopra, P. K. (2009). Psychosocial system for work well-being: On measuring work stress by causal pathway. Total Quality Management, 20 , 563-580.

Karasek, R. A. (1979). Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24 , 285-308.

Kirschner, P.A., Sweller, J., & Clark,, R. E. (2006). Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work: An analysis of the failure of constructivist, discovery, problembased, experiential and inquiry-based teaching. Educational Psychologist, 41 , 75-86.

Legault, L., Green-Demers, I., & Pelletier, L. (2006). Why do high school students lack motivation in the classroom? Toward an understanding of academic amotivation and the role of social support. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98 , 567-582.

Lindblom-Ylanne, S. & Lonka, A. (2001). Students’ perceptions of assessment practices in a traditional medical curriculum. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 6, 121-140.

Lizzio, A., Wilson, K., & Hadaway, V. (2007). University students’ perceptions of a fair learning environment: a social justice perspective. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher

Education, 32, 195-214.

Lizzio, A. Wilson, K., & Simons, R. (2002). University students’ perceptions of the learning environment and academic outcomes: implications for theory and practice. Studies in Higher

Education, 27, 27-51.

Lizzio, A., & Wilson, K. (2010). Assessment in first-year: beliefs, practices and systems.

ATN National Assessment Conference , Sydney, Australia.

McCune, V. (2004). Development of first-year students’ conceptions of essay writing. Higher

Education, 47, 257-282.

Mc Dowell, L. (1995). The impact of innovative assessment on student learning. Innovations in Education and Training International, 32, 302-313.

26

Mc Dowell, L., Smailes, J., Sambell, K., Sambell, A., & Wakelin, D. (2008). Evaluating assessment strategies through collaborative evidence-based practice: can one tool fir all?

Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 45 , 143-153.

Miller, M.C. & Parlett, M.R. (1974). Up to the mark: A study of the examination game .

London: Society for Research into Higher Education.

Pass, F., Renkl, A., & Sweller, J. (2003). Cognitive load theory and instructional design:

Recent developments. Educational Psychologist, 38, 1-4.

Race, P. (2010).

Making learning happen: A guide for post-compulsory education . London,

Sage.

Ramsden, P. (1992). Learning to teach in higher education , Routledge, London.

Ryan, R. M. (1995). Psychological needs and the facilitation of integrative processes. Journal of Personality, 63, 397-427.

Sambell, K., Mc Dowell, L., & Brown, S. (1997). “But is it fair?” : An exploratory study of student perceptions of the consequential validity of assessment. Studies in Educational

Evaluation, 23, 349-371.

Savin-Baden. M. (2004). Understanding the impact of assessment on students in problembased learning. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 41 , 223-233.

Schaufeli, W. B., Martinez, I., Marques-Pinto, A., Salanova, M., & Bakker, A. (2002).

Burnout and engagement in university students. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 33 ,

464-481.

Scouller, K. M. (1997). Students’ perceptions of three assessment methods: Assignment essay, multiple choice question examination, short-answer examination. Research and

Development in Higher Education, 20 , 646-653.

Segers, M., Dierick, S. & Dochy, F. (2001). Quality standards for new modes of assessment:

An exploratory study of the consequential validity of the Overall test. European Journal of the Psychology of Education, 16, 569-586.

Snyder, B. R. (1971). The hidden curriculum , New York, Knopf.

Stajkovic, A. D., & Luthans, F. (1998). Self-efficacy and work-related performance: a meta analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 124 , 240-261.

Thompson, K., & Falchinov, N. (1998). “Full on until the sun comes out”: the effects of assessment on student approaches to studying. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher

Education, 23, 379-390.

Trigwell, K. & Prosser, M. (1991). Improving the quality of student learning: the influence of learning context and student approaches to learning on learning outcomes, Higher Education,

22, 251-266.

27

Wehlburg, C.M. (2010). Assessment practices related to student learning: Transformative assessment. In K. Gillespie & D. Robertson (Eds.), Guide to faculty development (2 nd Ed.

., pp.

169-184). San Francisco, Jossey-Bass

28

Table 1: Structure of first-year students’ appraisal of assessment tasks

Item Description

1 This assessment task requires us to learn a lot of material

2 The weighting of this task is sufficiently high for me to be concerned about how it will impact on my overall grade

3 This assessment task requires us to really think about the material

4 This assessment task requires me to demonstrate mastery of skills

5 This assessment task makes sense to me given the learning objectives of this course

6 I can see how doing this assessment task will develop my academic skills

7 I have the skills required to do this assessment task

8 I have recently done something similar to this task

9 My sense is that there will be good mechanisms in place to support students with this assessment task

10 I think the weighting of this assessment task matches the time required to do it

11

It’s fairly safe to ‘have a go’ with this assessment task

12 I feel that this assessment task is organised fairly

13 I think this assessment task is at an appropriate level for first-year students

14 This assessment task allows individual students sufficient personal control over how well they will perform

15 I have a good sense of the workload involved in this task

Percentage of variance

Loadings

Factor 1 Factor 2

.88

.87

.84

.83

.72

.71

.70

.68

42.43

.80

.76

.74

.72

.71

.71

.68

39.21

29

Table 2 Correlations of assessment appraisal factors and student characteristics

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13

1 Age

2 Gender

3 University entrance score

4 First in family at university

5 Language (ESL)

6 Equity group membership

7 Factor 1 Task motivational content and value

1

-.04

-.05

.16 1

.05

.03

.08 .02 1

-.03 .16 -.04 1

.05

.06

.08

.05

1

.09 1

.01 .04 .04 .06 .10 .06 1

8 Factor 2 Task manageability

9 Task confidence

10 Task anxiety

-.02

-.04

-.04

.08

.12

.02

.02

.15 -.02

.07

.10

.05

.06

.06

.03

.09

.07

.06

.67**

.06

.09

1

.46** 1

.48** .76** 1

11 Task learning orientation .02 .06 .06 .08 .09 .04 .38 ** .39* .41** .66** 1

12 Task achievement orientation -.02 .10 .05 .08 .05 .08 .37** .34

** .38** .68** .77** 1

13 Semester 1 GPA .07 .02 .03 .16 -.02 .10 .09 .08 .04 .08 .11 .09 1

Notes: *p < .05; ** p<.01; GPA = Grade Point Average.

30

Perceived

Assessment

Motivation

Value

.61*

Task Learning

Orientation

.66

Task Achievement

Assessment

Task

Engagement

Orientation

.84

.68 .31

Perceived

Assessment

Manageability

.36

Assessment

Task Efficacy

.90

Task Confidence

.55

Task Anxiety

Note: * p < .005; All other associations p < .0001.

Figure 1 Structural equation model of the influence of first-year students’ appraisal of assessment on their reported efficacy and engagement.

31

Perceived

Assessment

Motivation

Value

Exam (.76)*

Lab report (ns)

Essay (ns)

Oral Pres (.50)**

Assessment

Task

Engagement

Exam (.40)***

Lab report (.27)**

Essay ( ns)

Oral Pres. (ns)

Exam (ns)

Lab report (ns)

Essay (.42

)*

. Oral Pres. (ns)

Perceived

Assessment

Manageability

Exam (ns)

Lab report (ns)

Essay (.33)**

Oral Pres.(.21)*

Assessment

Task

Efficacy

Assessment

Outcome

Exam (ns)

Lab report (ns

Essay (ns).

Oral Pres. (ns)

Note: ns = non significant association; *** p < .001; ** p < .01; * p < .05

Figure 2: Structural equation models of the influence of first-year students’ appraisal of exam, laboratory report, essay and oral presentation assessment tasks on their reported efficacy, engagement and outcomes

32