Cardiovascular health among immigrants in Sweden

advertisement

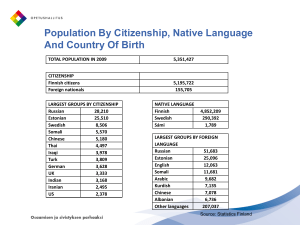

1 Cardiovascular health among immigrants in Sweden Sammy Zwackman, MD. Resident of internal medicine and cardiology Department of medicine Värnamo Hospital, Jönköping County Council Project supervisor: Jan-Erik Karlsson, MD, PhD. Jönköping County Council 2 Title Cardiovascular health among immigrants in Sweden Supervisor Jan-Erik Karlsson, MD, PhD. Jönköping County Council. Co-workers and contributors Mats Nilsson, PhD, Futurum, JönköpingCounty Council Tomas Jernberg, MD, PhD. KarolinskaUniversity Hospital. Background Sweden has changed steadily since the 1960s in regard to its population. Both labor immigrants and refugees have contributed to a more heterogeneous citizenry. These new residents have brought unique hereditary and environmental properties with them. Scientifically it provides an extraordinary opportunity to study this distinctive group from a cardiovascular point of view. It has previously been demonstrated that immigrants have a worse risk profile in respect to cardiovascular illness compared to ethnic Swedes (1). There is a higher preponderance of unhealthy habits and risk factors for coronary artery disease. It could constitute a remnant risk from the country of birth or it could partially explain the stress and difficulties that the process of immigration pose when leaving the ancestral and cultural land of birth (2). Emigration from a high-risk country to a low risk country in context of cardiovascular disease lowers the burden of coronary artery disease. Despite this fact a certain degree of increased 3 risk is transferred to the next generation (1, 3). Studies have also found that there is a strong association between immigration and prevalence of hypertension and smoking (4). Diabetes type 2 is more prevalent in European immigrants in comparison to ethnic Swedes. However among non-European immigrants the prevalence of diabetes type 2 is six times greater than their Swedish counterparts. Dyslipidemia in combination with low health awareness and low compliance have also been elucidated in this group (5, 6, 7). Socioeconomic factors have been suggested in order to explain the increased incidence of first myocardial infarction (MI) among immigrants. Most probably there are some external factors creating this discrepancy (8). A Swedish research team from Malmö University Hospital has conducted studies in this field. Their findings corroborate the aforementioned study results. Their results reveal that both cardiovascular mortality and morbidity is higher both in men and women living in less affluent areas in Malmö, Sweden (9). The same is also applicable in survival after 28-days, 3 and 4.5 years in patient from areas with low socioeconomic status, which has been defined by percentage of foreign born residents, unemployment level and annual income (10, 11). Taking into account the aforementioned studies, it should be pointed out that these papers are based on older patient data. Almost entirely all patients are from local registries entered in 1970s, 1980s and 1990s. Both diagnostic and therapeutic regimes have changed which merits a new look into this patient category. Furthermore patients in these studies are concentrated in same geographic area such as Malmö, which is not representative for Sweden entirely. Malmö according to Swedish Board of Health and Welfare has higher incidence of cardiovascular disease then the national average. It should be pointed out that Malmö has also changed its character. It has been transformed from the predominantly blue-collar 4 employment market into a white-collar professional market. A new university has been established and the percentage of immigrants has also been increased. Demographic changes are also evident in this group with the increasing number of second-generation immigrants. The latter has never been studied very thoroughly before. Moreover in the previous studies the fact of being foreign-born was equated with low socioeconomic status regardless of level of education. Both immigrants and Swedes living in areas of low socioeconomic status have been shown to have a poor survival prospects and a higher incidence of cardiovascular disease. This fact has been indirectly correlated to immigrants having a higher risk of cardiovascular disease. This is irrespective of duration of stay in Sweden, socioeconomic status on individual level and the fact that immigrants are not a homogenous group. Additionally the groups are divided into two homogenous groups of ethnic Swedes versus immigrants irrespective of the fact that immigrants are a highly heterogeneous group. To our knowledge no trials have been conducted on national or multi-center level on the new patient data from the Swedeheart register. Thus there are gaps in the knowledge, which need to be bridged especially as the diagnostic and therapeutic options have been increased and the mortality and morbidity of cardiovascular patients have been affected positively. However, so far we have no data elucidating the prognostic course of immigrant patients. The secondary prevention in the SEPHIA register has not been studied at all. Since previous studies indicate differences in risk factors, morbidity and mortality between ethnic Swedes and immigrant patients, it would be only logical to have a different approach to these patients in the secondary preventive strategy. Perhaps it needs to be tailored and individualized. However this approach cannot be implemented until we extract novel 5 knowledge from the contemporary data in regard to the effectiveness of the current therapy. Thereafter future intervention could be tailored on the individual basis. Aims The aim of this study is to answer; 1. Is there a relation between AMI and country of country/region of birth? 2. Does the relation between AMI and country/region of birth change in respect to duration of residency in Sweden? 3. Do immigrants and ethnic Swedes get the same evidence-based initial treatment of AMI (medication, primary PCI etc.)? 4. Is there a difference in lifestyle changes (physical exercise, tobacco use) between ethnic Swedes and immigrants after an MI? 5. What does happen to blood pressure, lipid profile and diabetes in Swedes versus immigrants after an MI? 6. Is there a difference in survival rate after 28 days and one year in these groups? 7. Does the long-term survival, for instance 5 years survival rate, after an MI differ in Swedes and immigrant patients? 8. Do immigrants get the same evidence-based secondary prevention after an MI? 9. Are immigrant women treated in accordance with evidence-based guidelines and does it differ in comparison to Swedish women? 10. (Is there a difference in acute versus planned PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention, in these two groups?) 6 Method The accumulated data in the Swedeheart register (which constitutes RIKS-HIA, SEPHIA, SCAAR and Heart Surgery register) will be used. In Swedeheart about 80000 entries are registered annually whereof circa 20000 are MIs. For this project the data from 2006-2010, will be retrieved. In Swedeheart patients are registered upon admission to ICCU (intensive cardiac care unit) and CCU cardiac care unit together with information about cardiovascular history, symptoms, diagnostic findings and treatments. This information is easily retrieved through unique Swedish social security number, which is universally employed in Sweden. This information will be then matched with the registers from Statistics Sweden (which has the data in regard to country of birth, immigration date, duration of residency in Sweden and socioeconomics state. See Annex 3) and statistical data from the National Board of Health and welfare. The latter has access to registries with data including diagnosis, hospitalizations, medications, country of birth and last date of immigration, marital status and gender. The first step is to subdivide all subjects in two groups of ethnic Swedes and immigrants. We have defined immigrants as individuals who were themselves born outside Sweden or have at least one parent born outside Sweden. Immigrants are also partitioned into clusters based on being first or second generation immigrant. Furthermore the immigrants are sectioned into different countries or regions of origin in order to make the data more manageable (Annex 1). Subsequently these cohorts will be compared to each other in order to address the aims of the study. Appropriate statistical methods will be used for data analysis. 7 Relevance of the study Immigrants constitute a significant part of the Swedish society contributing to its cultural and material wealth. Previous studies have indicated a poor outcome in this group, which merits investigating the persistence of these differences and adherence to guidelines in treating immigrants. The outcome of the study would be utilized in prospective interventional studies in the future. Ethics We plan to send an application for ethical review of the project to the regional ethical committee in Linköping. All patient data will be treated in accordance to the Swedish laws. The patient will be identifiable by the Swedish social security number when the data is initially retrieved from the registries. In further effort to protect the patient integrity and privacy, in our database we will designate each patient a unique identification number, from which he/she will not be traceable. The key will be kept at a safe location. In order to avoid stigmatizing specific immigrant nationalities, immigrants have been clustered into regional cohorts based on their country of birth. This clustering is based on geographic proximity. Funding Futurum has granted 1.5 months paid leave in order to launch this project. A sum of 5000 kronor has also been awarded for the fee of ethical review of the project. A private health provider, Familjeläkarna I Sverige AB, has promised 20 000 kronor in grants. Further financial support is needed. 8 Timetable It is under construction. 1. Final review of the application to ethical rev. 2012-12-19 2. Application to ethical review board 2013-02-25 3. Application to Futurum for funding 2013-03-31 4. Application to FORSS for funding 2013-04-01 5. Meeting with Mats Nilsson ? 6. Application for other donors Dec 2012 - April 2013 7. Consulting Swedeheart and Epistat at UCR Jan – April 2013 8. Start the process of post graduate admission April - 2013 9. Retrieving data from different sources Jan – August 2013 10. Building up the database August 2013- 11. Start analyzing data, consulting Epistat at UCR Sep 2013- 12. First article ready to be sent for publication Jan 2015. 9 References 1. Dotevall A, Rosengren A, Lappas G, Wilhelmsen L. Does immigration contribute to decreasing CHD incidence? Coronary risk factors among immigrants in Göteborg, Sweden. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2000; 247: 331-339. 2. Gadd M, Sundquist J, Johansson S-E, Wändell P. Do immigrants have an increased prevalence of unhealthy behaviours and risk factors for coronary heart disease? European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. 2005; 12 (6): 535541. 3. Jartti L, Rönnemaa T, Raitakari O T, Hedlund E, Hammar N, Lassila R, Marniemi J, Koskenvuo M, Kaprio J. Migration at early age from a high to a low coronary heart disease risk country lowers the risk of subclinical atherosclerosis in middle-aged men. Journal of Internal Medicine. 265; 345-358. 4. Koochek A, Miramiran P, AziziTohid, Padyab M, Johansson S-E, Karlström B, Azizi F, Sundquist J. Is migration to Sweden associated with increased prevalence of risk factors for cardiovascular disease? European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. 2008; 15(1): 78-82. 5. Wändell PE, Gåfvels C. High prevalence of diabetes among immigrants from nonEuropean countries in Sweden. Prim Care Diabetes. 2007;1: 13-16. 6. Alastalo H, Raikonen K, Pesonen AK, Osmond C, Barker DJ, Kajantie E, Heinonen K, Forsen TJ, Eriksson JG. Cardiovascular health in Finnish war evacuees 60 years later. Ann Med. 2009; 41(1):66-72. 7. Langllier B A, Garza J R, Glik D, Prelip M I, Brookmeyer R, Roberts C K, Peters A, Ortega A N. Immigration disparities in cardiovascular disease risk factor awareness. J Immigrant Minority Health. 2012; 01 January (online paper). 8. Hedlund E, Lange A, Hammar N. Acute myocardial infarction in immigrants to Sweden. Country of birth, time since immigration, and trends over 20 years. Eur J Epidemiol. 2007; 22:493-503. 9. Engström G, Berglund G, Göransson M, Hansen O, Hedblad B, Merlo J, Tydén P, Janzon L. Distribution and determinants of ischemic heart disease in an urban population. A study from the myocardial infarction register in Malmö, Sweden. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2000:588-596. 10. Gerward S, Tydén P, Engström G, Hansen O, Janzon L, Hedblad B. Survival rate 28 days after hospital admission with first myocardial infarction. Inverse relationship with socio-economic circumstances. Journal of Interanal Medicine 2006:164-172. 11. Tydén P, Engström G, Hansen O, Berglund G, Hedblad B, Janzon L. Myocardial infarction in an urban population: worse long term prognosis for patients from less affluent residential areas. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;785-790. 10 Annex 1 Country or region of 1. Sweden 2. Norway 3. Denmark 4. Finland 5. The Balkans; Serbia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Macedonia, Slovenia, Kosovo, Albania, Greece, Romania, Turkey, Bulgaria, Cypress 6. Eastern Europe; Russia, Ukraine, Moldova, Belarus, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Estonia, Georgia, Latvia, Lithuania, The Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia. 7. Northern Europe; Austria, Germany, Liechtenstein, Switzerland, The Netherlands, Ireland, Great Britain, Sweden, Denmark, Iceland, Norway and Finland. 8. Southern Europe: France, Portugal, Spain, Italy, France, San Marino, Monaco, Malta 9. Southeast Asia; Japan, China, Mongolia, Korea, Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, Burma, Eat Timor, Brunei, Singapore 10. Central and South Asia; Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal 11. Middel East; Egypt, United Arab Emirates, Iraq, Iran, Israel, Yemen, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria. 12. North America; Canada, USA, Mexico. 13. Central and South America; Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Jamaica, Dominican Republic, Haiti, Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Columbia, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru, Surinam, Uruguay, Venezuela 14. Africa; Algeria, Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Central African Republic, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Ivory Coast, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Cameron, Kenya, Congo, Congo-Brazzaville, Lesotho, Liberia, Libya, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Morocco, Mauritania, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Sudan, South Africa, Tanzania, Chad, Togo, Tunisia, Zambia, Zimbabwe. 15. Miscellaneous; Australia, New Zeeland, Fiji. 11 Annex 2 Questions to SCB 1. Country or region of birth 2. At least one parent born outside Sweden 3. First date of immigration to Sweden 4. Socioeconomic status 12 Annex 3 Variables fromSwedeheart/RIKS-HIA 1. Risk factors - Previous MI - Other ailments -Medications - BMI - Line of work - smoking - other type of tobacco usa 2. Primary ECG for treatment decision 3. Physical state at arrival 4. Acute revascularization 5. In-hospital work-up 6. Treatments 7. Complikations 8. 28 day resp1 year mortality 9. Medications upon discharge 10. Planned procedures after discharge 11. follow-up