Binge eating in binge eating disorder: A breakdown of emotion regulatory process?

Simone Munsch a,⁎, Andrea H. Meyer b, Vincent Quartier a, Frank H. Wilhelm c

a

b

c

University of Fribourg, Department of Psychology, 2, Rue de Faucigny, CH-1700 Fribourg, Switzerland

University of Basel, Faculty of Psychology, Department of Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, Division of Applied Statistics in Life Sciences, Missionsstrasse 62a, CH-4055 Basel, Switzerland

University of Salzburg, Institute of Psychology, Department of Clinical Psychology, Psychotherapy, and Health Psychology, Hellbrunnerstrasse 34, A-5020 Salzburg, Austria

a b s t r a c t

Current explanatory models for binge eating in binge eating disorder (BED) mostly rely on models for bulimia

nervosa (BN), although research indicates different antecedents for binge eating in BED. This study

investigates antecedents and maintaining factors in terms of positive mood, negative mood and tension in a

sample of 22 women with BED using ecological momentary assessment over a 1-week. Values for negative

mood were higher and those for positive mood lower during binge days compared with non-binge days.

During binge days, negative mood and tension both strongly and significantly increased and positive mood

strongly and significantly decreased at the first binge episode, followed by a slight though significant, and

longer lasting decrease (negative mood, tension) or increase (positive mood) during a 4-h observation period

following binge eating. Binge eating in BED seems to be triggered by an immediate breakdown of emotion

regulation. There are no indications of an accumulation of negative mood triggering binge eating followed by

immediate reinforcing mechanisms in terms of substantial and stable improvement of mood as observed in

BN. These differences implicate a further specification of etiological models and could serve as a basis for

developing new treatment approaches for BED.

1. Introduction

The core feature of binge eating disorder (BED) comprises loss of

control and consumption of large amounts of food (American

Psychiatric Association (APA), 1994). Cognitive behavioral therapy

(CBT) approaches in BED are traditionally based on corresponding

models for bulimia nervosa (BN) and constitute the established

treatment for the majority of BED patients (Vocks et al., 2009). In BN,

negative mood has been shown to be an important antecedent by a

number of studies (Polivy et al., 1984; Agras and Telch, 1998; Waters et

al., 2001). According to the affect regulation model, individuals engage

in binge-purge behavior to alleviate negative mood (Polivy et al., 1984)

or by substitution of a less aversive mood state (trade off-theory,

Kenardy et al., 1996). Masking theory suggests that rather than

decreasing or substituting negative mood, binge eating serves as an

attribution for negative mood that masks other problems (Herman and

Polivy, 1988). In other words, negative affect can be blamed on binge

eating, which seems to be more controllable to the person than the

actual causes of distress. The escape theory (Heatherton and Baumeister, 1991) posits that binge eating represents an attempt to “escape”

from distressing self-awareness and to narrow attention to the

immediate physical surroundings or stimuli (e.g. food). As a secondary

effect, the hypothesized shift in awareness impedes higher level

⁎ Corresponding author at: University of Fribourg, Department of Psychology, 2, Rue

de Faucigny, CH-1700 Fribourg, Switzerland.

E-mail address: simone.munsch@unifr.ch (S. Munsch).

0165-1781/$ – see front matter © 2011 Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2011.07.016

cognitive activities such as inhibition and thus results in the release of

previously suppressed binge eating behavior (Engelberg et al., 2007).

Recent studies using ecological momentary assessment (EMA) to

overcome known limitations of retrospective recall (for an overview,

see Shiffman et al., 2008) convincingly demonstrate that, in line with

the affect regulation model, negative mood increases and positive

mood decreases before binge eating and vomiting, whereas after BN

events, negative mood decreases and positive mood increases again.

Binge-purge behavior in BN thus seems to be reinforcing itself by

improving mood (Engel et al., 2006; Smyth et al., 2007; Engelberg et

al., 2007). Another study from Crosby et al. (2009) investigating

patterns of mood in daily lives of bulimic individuals corroborates that

negative mood drives bulimic behavior.

Research regarding antecedents of binge eating in BED used to rely

on models derived from BN, although there seem to be differences with

regard to the binge cycle. For example, Hilbert and Tuschen-Caffier

(2007), in a comparison of BED with BN patients using EMA for multiple

assessments over a 2-days period found, that BED individuals not only

reveal less dietary restraint, they also experience less intense negative

mood than BN patients and tend to binge eat also when feeling only

moderately negative. Further, BED in contrast to BN individuals turned

out to be vulnerable to negative mood, in particular when they

concurrently suffered from high levels of general psychopathology

(Hilbert and Tuschen-Caffier, 2007). Together with another naturalistic

study from Stein et al. (2007) assessing antecedents and consequences

of binge eating at 7 intervals during 7 consecutive days, these findings

underline that also in BED negative mood was increased on binge eating

S. Munsch et al. / Psychiatry Research 195 (2012) 118–124

days compared to non-binge periods, whereas there were no such

differences for ratings of positive mood. On both studies, however,

contrary to existing emotion regulation models, negative mood

remained increased when measured immediately after binge eating in

student and patient populations (Hilbert and Tuschen-Caffier, 2007;

Stein et al, 2007). The cited studies shed light on possibly different

mechanisms driving binge eating in BED, but their findings remain

limited as they did not consider longer time intervals than one

measurement immediately after binge eating. As a consequence, the

time course of mood factors after binge eating in BED remains open.

Further limitations of the earlier studies concern the application of

solely the time-contingent sampling method of the Stein et al. study as

well as the short observation method of 2 days in the Hilbert et al. study.

In summary, current research about the preceding and maintaining

factors of binge eating in BED indicates distinct processes such as less

pronounced negative mood and a lack of immediate reinforcement in

terms of a fast and pronounced decrease of aversive mood states after

binge eating in BED. Thus, research on the concrete cues and reinforcing

mechanisms of binge eating in BED may help to further specify

etiological models and to engage in developing specialized and

individualized treatment options for BED patients.

The present study aims at extending findings of current naturalistic

studies regarding binge cycles in BED and sets out to investigate in more

detail the binge cycle in BED. Besides negative mood, we additionally

included potentionally meaningful mood factors such as positive mood

and tension. We followed the temporal course of these characteristics

before, during, and after binge eating on binge and, for comparison, on

non-binge days in a small sample of overweight to obese female BED

individuals randomized for participation in a treatment trial for BED. To

minimize influences of retrospective memory recall, participants were

investigated using ecological momentary assessment (EMA). Relative to

traditional questionnaire-based methods, EMA reduces biases associated

with retrospective recall by shortening the interval between an

experience and its recall. Further the EMA method is thought to enhance

ecological validity as it is carried out within the naturalistic environment

of the participant (Shiffman et al., 2008).

The following research questions were investigated: First, we

examined whether the daily courses of the different aspects of mood

varied between binge and non-binge days. Second, to shed light on

binge cycles in BED, we not only examined the pre- but also the postbinge phase. To our knowledge, we are the first to examine

consequences of binge eating not only immediately after but during a

prolonged time span during the day after binge eating. Third, according

to Smyth and colleagues, we further acknowledge that the binge eating

event itself is affect-laden and probably influences estimates recalled

immediately after binge eating. Therefore, we analyzed the trajectories

of mood and tension by including or excluding the 30 min immediately

prior to and the 30 min following the binge episode (Smyth et al., 2007).

Fourth, to account for findings in the current literature (e.g., Hilbert and

Tuschen-Caffier, 2007), we additionally included specific participant

characteristics related to eating disorder and clinical features, i.e.

comorbidity status, body-mass index (BMI), duration of the disorder,

degree of depressiveness and severity of eating disorder pathology,

which may all potentially moderate the temporal trend of negative

mood, positive mood, and tension on binge eating days.

2. Methods

119

Psychiatric Association (APA), 2000) according to a specialized eating disorder

interview (see diagnostic assessment below). Of the 136 individuals who were initially

contacted, 28 female obese individuals with BED fulfilled these inclusion criteria. As

individuals participated in a randomized trial to evaluate treatment efficacy of a shortterm CBT approach, individuals were excluded if they were pregnant, participated in a

diet or psychotherapy, received weight loss medications (currently or during the last

3 months), had previous surgical treatment of obesity, or met DSM-IV-TR (American

Psychiatric Association (APA), 2000) criteria for mental disorders warranting

immediate treatment, as those factors might have influenced treatment response. As

patients who never exhibited a binge during the entire week were excluded from all

analyses (see results section), the final sample consisted of 22 female obese individuals

with an average age of 45.5 years (S.D. = 12.0, range = 21–65), a BMI (kg/m 2) of 33.4

(S.D. = 6.8, range = 24.4–55.5), a Beck Depression Inventory score of 12.8 (S.D. = 8.7,

range = 3–32), an Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) total score of 2.43

(S.D. = 0.86, range = 0.93–4.22), an average number of binges according to EDE of

15.6 (S.D. = 8.0, range = 4–30), and an average age of first manifestation of BED of 16.6

(S.D. = 12.2, range = 2–40). Six (27%) participants suffered from an additional affective

or anxiety disorder and one patient (3.6%) from a comorbid mental disorder on axis-II.

As only one male participant could be recruited, we excluded these data from our

analyses.

2.2. Measures and procedure

2.2.1. Diagnostic assessment

BED diagnosis and associated eating disorder pathology were assessed using the

Eating Disorder Examination (EDE, Fairburn and Cooper, 1993; Hilbert et al., 2004). The

German language screenings for mental disorders on axis-I (Mini-DIPS) (Margraf,

1994) and axis-II (SKID-II) (Wittchen et al., 1997) were administered to assess current

and lifetime mental disorders. Interviewers were trained by the principal investigator

(S.M.). In cases of discordance of interviewers regarding the diagnoses, the diagnostic

process was reevaluated using video tapes of the diagnostic interviews.

2.2.2. Daily electronic diary, ecological momentary assessment (EMA)

All patients gave written informed consent and were offered free treatment. Data

were collected for 7 days before treatment onset using a personal digital assistant (PDA,

Palm Tungsten E). According to Smyth et al. (2007), time-contingent assessment

intervals were decreased during the day to adjust for an increased likelihood of binge

eating in the evening. Time intervals were scheduled as follows: The first alarm was

preset individually at 1.5 h after awakening, the second alarm 5 h after the first, the

third alarm 4 h after the second, the fourth alarm 3 h after the third and the fifth alarm

2 h after the fourth alarm. For event-contingent monitoring, participants were

instructed to fill in the questionnaire whenever binge eating occurred. Participants

were asked to fill in the questionnaire within a 30-min interval. Please refer to Munsch

et al., (2009) for further details including test-theoretical characteristics of the

questionnaires used in this study. Questions were either dichotomous, suggesting a yes

or no response, e.g., item 1 “Did you experience binge eating since your last entry?”, or

corresponded to a computerized Likert-type or visual analogue scale (VAS) scale.

Questionnaires were programmed and displayed using Pendragon Forms software

(Pendragon Software Corporation, Libertyville, IL, USA; unpublished questionnaire

available from the authors). Feasibility of EMA, i.e. practicability (“Did you experience

any difficulties in filling in the electronic diary?”), acceptability (“How did you feel

during the week with the electronic diary entries?”, “Did the electronic diary alarm go

off too often?”, “Was your daily routine disturbed?”; correlations among items were

between 0.47 and 0.72; mean = 7.19, S.D. = 2.24, N = 20), representativeness (“Did the

previous week correspond to your usual weekly routine?”; mean = 7.21, S.D. = 2.55,

N = 17), and signal-compliance (“Was it possible for you to fill in the electronic diary

30 min after the signal?”; mean = 7.05, S.D. = 2.28; Fahrenberg (2006)) were all

measured on an 11-point Likert-type scale from 0 (“not at all”) to 10 (“yes, exactly”)

according to a self-developed exit questionnaire, EXQ (Munsch et al., 2009). EMAbased signal-compliance (filling in of the electronic questionnaire within 30 min after

being alarmed) and recording compliance (rate of overall responses to time-contingent

signaling) were all assessed by EMA. Reactivity was registered according to the EXQ

(“Did the frequency of binge eating change during the diary period?”, “Did you focus

more on your psychological well-being?”, “Did you benefit from filling in the diary?”,

“Did the previous week correspond to your usual weekly routine?”; correlations among

items were between 0.48 and 0.70; mean of averaged items = 5.72, S.D. = 3.29, N = 16;

for detailed information see Munsch et al., 2009). EMA-based signal-compliance, i.e. the

proportion of the number of recordings starting within 30 min after the signal to the

total number of recordings was 0.87. Participants' mean absolute deviation of entry

from the scheduled alarms (in min) was 16.0 (median = 1.0, S.D. = 34.8, N = 722).

2.1. Participants

Data were collected from obese individuals with BED presenting for participation in a

treatment trial to evaluate the efficacy of a short version of a cognitive behavior

therapy (CBT) trial at the Department of Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy of the

University of Basel (Switzerland) (Schlup et al., 2009). The study was approved by the

local ethics committee of the University Hospital of Basel. Inclusion criteria for the

clinical trial included being aged between 18 and 70 years, having a BMI between 27

and 40 kg/m 2, being free from severe medical conditions such as diabetes, heart

disease, or endocrine disorders and meeting full DSM-IV-TR criteria for BED (American

2.2.3. EMA of binge eating, negative and positive emotions

After answering the electronically administered entry question (“did you

experience a binge episode”) with yes, exclusively objective binge eating (OBE, i.e.

binge eating defined as consuming unusually large quantities of food with a subjective

sense of loss of control) was assessed according to the German version of the EDE

(Hilbert et al., 2004; Munsch et al., 2009) (for a critical discussion of concordance rates

of EMA-based and self-report-based measures in order to assess binge eating in BED,

please see Munsch et al., 2009). Daily course of negative mood, positive mood, and tension

were assessed on a scale between 1 and 10 using the Mood Assessment Inventory (MAI,

120

S. Munsch et al. / Psychiatry Research 195 (2012) 118–124

German version by Feist and Stephan, 2007) developed for ambulatory assessment,

which contains five empirically derived subscales: negative mood, positive mood,

interest, tension, and sleepiness. Feist and Stephan (2007) reported sufficient

correlations (r = 0.60) of the Negative Mood Subscale with the Beck Depression

Inventory (BDI, Beck et al., 1961; Hautzinger et al., 1995) and good test–retest

reliability (r = 0.70) in a student sample. Based on clinical experience and literature on

mood in BED (Stickney and Miltenberger, 1999; Vanderlinden et al., 2001; Binford et al.,

2004; Engel et al., 2006; Smyth et al., 2007), we additionally included the following

adjectives in the electronic questionnaire: bored, stressed out, anxious, sad, tense,

lonely, and annoyed.

To combine the items of the MAI with the additional items, and to obtain a limited

number of reliable, valid and interpretable measures of mood, all items were entered

into an exploratory factor analysis using principal components as extraction and

varimax as rotation method. Items with loadings b 0.4 were excluded from further

analyses. Based on the Scree plot and the Kaiser criterion (excluding components with

Eigenvalues b 1.0), we obtained three different factors. These factors represent scale

scores, i.e., they were computed by taking the mean across all items which loaded

highly on them. The first factor, which explained 10% of the variance, was highly

correlated with the MAI-scale “negative mood” (r = 0.92) and was given this label. It

contained the MAI items discontented, depressed, and queasy plus the additional items

bored, anxious, lonely, and sad. The second factor, which explained 39% of the variance

was highly correlated with the MAI scale “tension” (r = 0.94) and received this label. It

contained the MAI items calm, nervous, and agitated plus the additional items stressed

out, tense, and annoyed. The third factor, which explained 15% of the variance, was

highly correlated with the two MAI scales “positive mood” (r = 0.92) and “interest”

(r = 0.94) and was given the label “positive mood”. It contained the MAI items

cheerful/merry, good, and happy of the positive mood scale, and fascinated, interested,

and not interested of the MAI interest scale, with no additional items. Factor scores

based on these three factors were then used as mood-related variables in subsequent

analyses.

2.2.4. Situational context of binge eating

These were assessed by the two questions “where are you at the moment?” and

“whom are you with?”. Answers were recoded into the two variables “being at

home/not at home” and “being alone/not alone“.

2.2.5. Trait specific characteristics moderating the impact of mood and tension on binge

eating

To analyze the moderating impact of participants' characteristics related to eating

disorder and clinical features on temporal trends of positive or negative mood and

tension during binge days, we included the following baseline variables: comorbidity

status, baseline BMI, duration of BED (years since first manifestation of BED), severity of

eating disorder pathology (measured by the global score, GS, of the EDE), and

depressiveness (measured by the BDI, Hautzinger, 1991).

For the temporal trend during both the pre- and post-binge phase, we included only

linear polynomials as polynomials of higher degree did not improve model fit (see

Appendix A).

Finally, Model 4 tested whether BMI, EDE global score, comorbidity status (y/n),

number of years since first manifestation of BED, and depressiveness (BDI) moderated

the temporal trends of negative mood, positive mood, and tension before and after the

first daily binge as assessed in Model 2. This model therefore included in addition to the

terms listed in Model 2 the moderator (main effect) plus the interaction between

moderator and time for the pre- and post-binge phase. Each moderator was tested in a

separate model.

Note that in all four models we did not include an individual random slope coefficient

b1i (Singer and Willett, 2003) as doing so would not have improved model fits. Mood

factors for negative mood and tension were both transformed logarithmically (natural) to

meet model assumptions. To analyze these models, we used the software SPSS 14.

Reported significances are based on an alpha of 0.05 unless otherwise specified.

3. Results

Of the 28 patients, 6 never exhibited a binge during the entire

week and were excluded from all analyses. These six patients did not

differ from those reporting one or more binges during the study

period with respect to age, educational level, BMI, BDI, BAI, EDE total

score, first manifestation of BED (years), and number of binge

episodes according to EDE (p N 0.05 for each t-test performed). For

the remaining 22 patients filling in the diary five times a day during

the entire week, a total of 770 possible time-contingent data entries

were possible. They actually completed 651 records, corresponding to a

compliance rate of 85%. In addition, 36 event-contingent data entries

were recorded, resulting in a total of 687 data entries of which 75

(11%) concerned binge episodes. Each patient had on average 0.49

binge episodes per day.

Most binge episodes occurred in the afternoon (52%, 12:00–18:00,

N = 39) and in the evening (39%, 18:00–24:00, N = 29); very few

were observed during the night (4%, 24:00–06:00, N = 3) and in the

morning (5%, 06:00–12:00, N = 4). Models 2 and 4 covered only binge

days and thus included 198 records and Model 3 in addition excluded

all measurements within 30 min before and after a binge episode and

included 149 records.

3.1. Situational context of binge eating

2.3. Statistical analysis

We used a random intercept model to analyze the data (Pinheiro and Bates, 2000).

Random intercept models are special types of linear mixed models in which each

individual is assumed to have his/her own intercept. This kind of model is suitable for

cases where each subject follows his/her own time schedule (i.e. both the number of

time points and the time interval are allowed to vary from subject to subject) which is

often observed in EMA based studies. The distinction between binge days and nonbinge days was based on whether at least one daily binge episode occurred or not. For

the precise model equations, please refer to Appendix A.

Model 1 tested whether the daily course of mood factors differed between binge

and non-binge episodes while allowing for a trajectory following a linear and quadratic

polynomial.

Model 2 tested for temporal trends in the mood factors before and after the

occurrence of the first daily binge. Hence we introduced an additional dummy variable

distinguishing between the pre- and post-binge phase during binge days that allowed

us to model the temporal trends of these two phases independently. This model

contained the interactions between time and each of the two dummy variables pre- and

post-binge phase. For the temporal trend during the pre-binge phase, we included

polynomials up to 5th degree as doing so improved model fit. The inclusion of

polynomials higher than linear during the post-binge phase in contrast did not improve

model fit and we therefore only used a linear trend (see Appendix A for the exact model

equation). The variable time was centered to the first binge episode, separately for each

patient and day. For this analysis we used a subsample covering binge days only. We

omitted days starting with a binge episode as such cases could not have been analyzed

using Model 2 since there would have been no mood factor ratings preceding a binge

rating. This concerned 14 binge episodes stemming from 6 persons. We also omitted all

data points including and following the second binge episode within the same day as

the corresponding mood factor values might have been influenced by the first binge

episode. This concerned 16 binge episodes coming from 12 persons.

According to Smyth et al. (2007), we tested in Model 3 whether trends of values of

mood factors prior to the first binge could still be observed after excluding the values at

the binge themselves. Thus in this model the values covering the 30 min immediately

prior to and the 30 min following the binge episode were excluded to prevent

recordings immediately associated with the binge event influencing the model results.

The proportion of participants being at home rather than not at

home was 67% (N = 576) during non-binge periods, 83% (N = 29)

immediately before a binge episode and also 83% (N = 35) during a

binge episode. In the same way the proportion of participants being

alone rather than not alone was 46% (N = 576) during non-binge

periods, 72% (N = 29) immediately before a binge episode and 63%

(N = 35) during a binge episode.

3.2. Daily course of negative mood, positive mood, and tension (Table 1)

3.2.1. Model 1

Values for negative mood were significantly higher during binge

than non-binge days without showing any particular daily trend

during either binge nor non-binge days. Values for positive mood

were significantly lower during binge than non-binge days, especially

later during the day. However, no significant daily trends could be

found. Values for tension did not vary between binge and non-binge

days but increased during the day until the afternoon and then

decreased again, both during binge and non-binge days.

3.2.2. Model 2

The average time period between the first measurement in the

morning and the first reported binge episode was 7.23 h (S.D. = 3.29).

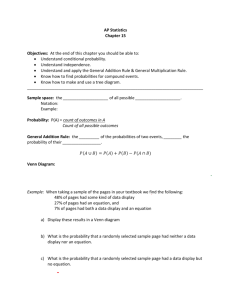

For negative mood, there was a significant curvilinear increase

immediately before the first binge episode, with particularly high

rates of increase shortly before the first binge (solid lines in Fig. 1a).

The linear post-binge trend was significantly negative. Positive mood

S. Munsch et al. / Psychiatry Research 195 (2012) 118–124

121

Table 1

Daily course of negative mood, positive mood and tension. Regression coefficients for statistical models 1–3.

ln(negative

mood) × 1000

β (SE)

Model 1

Model 2

Model 3

β10 intercept: estimated value at 2>h/>pm on a non-binge day

β11 difference between binge and non-binge days at 2 pm

β12 linear trend at 2 pm on a non-binge day

β13 quadratic trend on a non-binge day

β14 difference in linear trend at 2 pm between binge and

non-binge days

β15 difference in quadratic trend between binge and

non-binge days

905 (104)

223 (49.8)

− 0.1 (4.40)

− 0.28 (0.88)

7.12 (6.85)

0.22 (1.19)

ln(positive

mood) × 1000

β (SE)

t

8.74⁎⁎⁎

4.48⁎⁎⁎

tension × 1000

t

22.0⁎⁎⁎

− 2.48⁎

− 0.02

− 0.36

1.04

6045 (275)

− 422 (170)

17.1 (15.1)

− 3.59 (3.00)

− 24.5 (23.4)

1.14

− 1.19

− 1.05

0.18

− 10.3 (4.05)

− 2.53⁎

13.1⁎⁎⁎

5.19⁎⁎⁎

4579 (355)

− 2319 (710)

445 (102)

4.36⁎⁎⁎

80.5 (20.5)

t

1073 (103)

57.3 (52.9)

− 2.64 (4.67)

− 2.09 (0.93)

5.32 (7.27)

10.7⁎⁎⁎

1.08

− 0.56

− 2.25⁎

0.46

1.19 (1.26)

0.95

12.9⁎⁎⁎

− 3.26⁎⁎

1251 (119)

651 (182)

10.5⁎⁎⁎

3.59⁎⁎⁎

− 920 (396)

− 2.32⁎

316 (101)

3.12⁎⁎

3.92⁎⁎⁎

− 143 (79.5)

− 1.79

57.6 (20.3)

2.83⁎⁎

6.20 (1.71)

3.64⁎⁎⁎

− 9.41 (6.61)

− 1.42

4.43 (1.69)

2.62⁎⁎

β25 quintic trend during pre-binge phase immediately before first daily binge

β26 linear trend during post-binge phase

β30 intercept: estimated value at first daily binge

β31 difference between estimated values 30 min before and 30 min

after first daily binge

0.17 (0.05)

− 55.0 (16.3)

785 (114)

− 533 (137)

3.38⁎⁎⁎

− 6.86⁎⁎⁎

6.86⁎⁎⁎

− 3.88⁎⁎⁎

− 0.22 (0.19)

173 (62.8)

6472 (401)

1103 (512)

− 1.13

2.76**

16.2⁎⁎⁎

2.15⁎

β32 linear trend during pre-binge phase

β33 linear trend during post-binge phase

− 26.0 (13.5)

− 47.1 (22.1)

− 1.93

− 2.14⁎

β20 intercept: estimated value at first daily binge

β21 linear trend during pre-binge phase immediately before

first daily binge

β22 quadratic trend during pre-binge phase immediately before

first daily binge

β23 cubic trend during pre-binge phase immediately before first

daily binge

β24 quartic trend during pre-binge phase immediately before first

daily binge

1379 (105)

950 (183)

β (SE)

103 (50.5)

50.1 (82.2)

⁎ p b 0.05.

⁎⁎ p b 0.01.

⁎⁎⁎ p b 0.001.

showed a significant curvilinear decrease before the first binge

episode, with strongest rates of decrease shortly before the first

binge, followed by a linear increase during the post-binge phase,

which was also significant (solid lines in Fig. 1b). For tension there

was a significant curvilinear increase before the first binge episode,

which was also most pronounced shortly before the first binge (solid

lines in Fig. 1c). The post-binge trend for tension was significantly

negative.

3.2.3. Model 3

When the values up to 30 min before and 30 min after the first

binge were omitted, a different pattern was observed. Values for

negative mood and tension now decreased and positive mood

increased during the pre-binge phase, these trends being significant

for positive mood and failing to reach significance for negative mood

(Fig. 1a–c, broken lines). Trends during the post-binge phase, in

contrast, were similar to those in Model 2 for all three mood factors.

Thus negative mood and tension both decreased and positive mood

increased, these trends being significant for negative mood only. Note

that for each mood factor predicted values 30 min after the first daily

binge were significantly higher (negative mood and tension) or lower

(positive mood) than those 30 min before it.

3.2.4. Model 4

The trait-specific factor comorbidity status moderated the temporal course of tension prior to the first daily binge (not shown in table):

patients suffering from comorbid mental disorders had higher rates of

increase for tension immediately before the first daily binge than

patients without comorbid disorder. Also, patients with higher

depressiveness had lower rates of increase for tension immediately

before the first daily binge than patients with lower depressiveness.

The other person-specific characteristics, baseline BMI, years since

first manifestation of a binge episode, and EDE total score did not

moderate the course of negative or positive affect and tension before

and after the first daily binge.

2.04⁎

0.61

0.12 (0.05)

− 38.3 (16.2)

867 (124)

− 308 (136)

2.44⁎

− 2.37⁎

6.97⁎⁎⁎

− 2.26⁎

− 22.1 (13.4)

− 25.3 (22.0)

− 1.65

− 1.15

122

S. Munsch et al. / Psychiatry Research 195 (2012) 118–124

4. Discussion

The present study is to our knowledge the first to investigate daily

courses of mood and tension experienced during binge and non-binge

days and before and after binge eating, thereby covering an extended

time span in the natural environment of treatment-seeking women

with BED.

In general the study findings corroborate findings from studies on

BN and BED showing that negative mood ratings were higher and

positive mood ratings lower on binge days compared to non-binge

days (Smyth et al., 2007; Stein et al., 2007).

Considering binge days and temporal courses until the first daily

binge, we found that positive mood, negative mood and tension all

strongly deteriorated immediately before the first daily binge (see

Model 2), as has been observed in BN (Engelberg et al., 2007; Smyth

et al., 2007). It must be noted that in general and even during binge

eating values for mood factors, especially regarding negative mood

and tension, varied between 2.5 and 4 on a range of 1 to 10, which is

rather low (Fig. 1). Our analyses further revealed that the temporal

course of mood and tension was independent of eating disorder

severity or body weight. However, individuals suffering from

additional mental disorders were prone to higher increases in tension

shortly before the first daily binge than individuals without comorbid

disorders. Also more depressed individuals experienced a lower

short-term increase of tension before the first daily binge compared to

less depressed individuals.

Following the considerations of Smyth and colleagues, we

excluded the values covering the time span 30 min before and

30 min after the first binge as these measures could be influenced by

the affect-laden event of recent binge eating per se (Smyth et al.,

2007). In a BN sample, Smyth and colleagues found that even after

excluding these measures, accumulation of mood deterioration

remained a robust predictor of binge eating. In contrast, in our

sample of female BED individuals, excluding measures over the 1-h

interval resulted in a strikingly different pattern. We even observed a

slight improvement of mood up to 30 min before binge eating (Model

S. Munsch et al. / Psychiatry Research 195 (2012) 118–124

123

Fig. 1. Daily course of negative mood, positive mood, and tension before and after the first binge episode. Values for negative mood and tension were backtransformed from lntransformation. Solid lines denote predicted values from linear mixed models during binge days and refer to statistical Model 2. Broken lines denote predicted values when disregarding

values at the time of the binge (±30 min) and refer to statistical Model 3. Note that predicted values during non-binge days are not included. Grey lines denote means and 95% confidencelimits of observed values and were obtained by computing means and confidence limits of all observed values within defined time intervals. Intervals relative to the time variate centered at

the first daily binge were: –6 h to –4 h/–4 h to –2 h/–2 h to b 0 h/time at first daily binge/N 0 h to + 2 h/+ 2 h to + 4 h/+ 4 h to + 6 h.

3) followed by an abrupt and significant deterioration (Model 2)

immediately before the binge. These findings seem to contradict affect

regulation theory as hypothesized in BN, where binge eating is

supposed to be the result of an accumulation of negative affect. In

contrast, our results indicate that binge eating in BED might rather be

the result of an immediate breakdown of emotion and impulse

regulation caused by sudden increases of negative affect and tension,

and a rapid decrease of positive affect. Our results are more in line

with the assumption of the escape theory (Heatherton and Baumeister, 1991) in which a short decrease in self-awareness is thought to

inhibit cognitive control and thus might contribute to triggering binge

eating. They are also consistent with Wegner's theory of ironic effects

of inhibitory mental control processes, resulting in a sudden shift

toward suppressed undesired behavior (Wegner, 1994). Further,

these findings underline the importance of the concepts of affect

lability and impulsivity, characterized by a trait-like tendency to

experience rapidly shifting affective states as risk factors for binge

eating in BED and BN (Svaldi et al., 2009; Anestis et al., 2010).

Regarding the long-term course of binge eating, our findings

indicate that after a mood deterioration immediately before a binge

episode a rather slow but lasting improvement over several hours

following the binge emerged (Fig. 1). Compared to the short-term

relief of distress after binge eating in BN due to both an increase of

positive and a decrease of negative mood, in BED relief of aversive

mood states after bingeing seems to be less pronounced and reveals

itself only if longer time frames are considered (Smyth et al., 2007).

124

S. Munsch et al. / Psychiatry Research 195 (2012) 118–124

This finding does not seem to be astonishing when compared with

binge cycles in BN, as these are normally finished by purging behavior

leading to immediate, even though short-term, relief. As in BED

suffering might decrease only gradually, this might explain why

previous studies focussing on the immediate effect of binge eating on

mood in BED did not indicate an improvement of mood as a function

of a binge episode (Hilbert et al., 2004; Munsch et al., 2009). To

investigate whether the slow improvements of negative and positive

mood after binge eating have reinforcing properties as in BN and

whether they contribute to the maintenance of binge eating in BED,

more frequent assessment time points after binge eating as well as

accompanying cognitions should be considered. Generally, reinforcement is considered more potent with closer time contingeny. Future

research should also focus on the investigation of the underlying

biological mechanisms such as physiological stress levels to further

investigate the different mechanisms in binge cycles between BED

and BN.

Possible criticisms include the lack of representativeness of our

study sample as it consisted of individuals fulfilling criteria to

participate in a randomized treatment trial. As only very few men

participated, we subsequently had to exclude them from our analyses.

Further, the underpowered sample size limits the possibility to detect

moderator effects of mood factors and the sampling time of 1 week

before treatment begin was rather short. Another limitation is that we

only registered objective binge eating episodes even though there are

now considerable data indicating that the only difference between

individuals suffering from objective compared to subjective binge

eating is with respect to increased body weight for objective binge

eaters (Mond et al., 2010). We further cannot exclude that

participants did not report all occurrences of binge eating, even

though we did not find any indications for a lack of compliance to the

EMA procedure. Participants rated EMA to be an acceptable and

feasible method in their responses to our exit questionnaire. They

further estimated that the 1-week assessment period was representative and that they did not feel that their binge eating patterns were

influenced by EMA (Munsch et al., 2009). Nevertheless, even selfreported EMA remains a retrospective assessment method and might

itself be subject to memory and reporting bias in terms of, for

example, mood-dependent recall. Future research could profit from

more fine-grained and simultaneous diurnal analyses of the emotional and cognitive characteristics and of shape and weight concern

before and after binge eating using new methods such as automatic

sound sampling, which provides observational data with short

sampling intervals but nevertheless low subject burden (Mehl et al.,

2001; Hilbert et al., 2009).

Overall our findings indicate that binge eating in BED might

represent the result of an immediate break-down of emotion and

impulse regulation attempts. After binge eating, in contrast to findings

from BN, we found a less pronounced and only slow recovery of mood

after binge eating in BED. With respect to therapeutic implications of

this result, we ought to develop stimulus control strategies to increase

alertness of considered individuals in order to prevent or detect first

signs of upcoming urges to binge as especially these individuals will

have pronounced difficulties to inhibit binge eating once it has

started. Often applied training of response prevention in order to

suppress unwanted behavior during states of high mental load may in

contrast further enhance ironic effects of suppression attempts and so

increase the probability of problematic behavior (Wegner, 2009).

Response-prevention strategies, such as the acceptance of stressful

events or the disclosure of mental states, may then be options to be

considered in further research and clinical practice.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at doi:10.

1016/j.psychres.2011.07.016.

References