TRANSACTIONS of the ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY

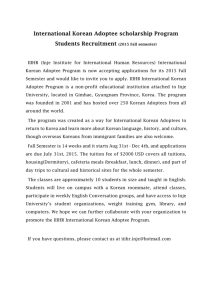

advertisement