Word - Whole Schooling Consortium

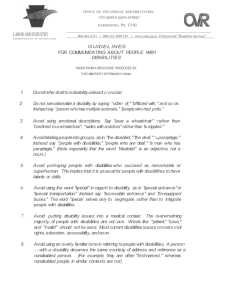

advertisement