An Overview of Activity Theory - E

advertisement

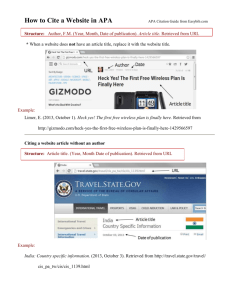

Running Head: AN OVERVIEW OF ACTIVITY THEORY An Overview of Activity Theory and Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development Robert Power Athabasca University 1 AN OVERVIEW OF ACTIVITY THEORY 2 Table of Contents An Overview of Activity Theory and Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development ......................................... 3 Activity Theory in Context............................................................................................................................. 5 Influence on Instruction ................................................................................................................................ 6 Resources for Further Study ......................................................................................................................... 7 References .................................................................................................................................................... 8 AN OVERVIEW OF ACTIVITY THEORY 3 An Overview of Activity Theory and Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development Activity Theory essentially describes how people use tools to interact with objects in order to satisfy a need. Activity Theory casts aside behaviorist descriptions of conditioned behaviors (Atwell, 2009; Wikipedia, 2012), stating that there is a goal to any human activity. In education, that goal could be either mastery of a skill or concept, or obtaining a credential (Atwell, 2009). Achieving goals requires an active relationship amongst three main elements (Chaiklin, 2003; Kaptelinin & Nardi, 2006; Murphy & Rodriguez-Manzanares, 2007). The first is the subject (or actor). This is the individual or group attempting to learn. The second is the object, which is the focus of the actors’ attention. The object could be an item or something less tangible, such as a concept (Wikipedia, 2012). The third element is the tools that facilitate interaction, which range from language to pencils, slide-rules, computers, and mobile devices. Tools extend the range of interactions with objects, but they also impose limitations (Atwell, 2009; Impedovo, 2011; Sharples, Taylor & Vavoula, 2011). Activity Theory states that this is because even the most complex tools are task specific, and their use is often governed by preconceived notions and rules. Humans interact within communities (even when acting as individuals), which creates perceptions and governs how we interact with objects, tools and each other (Chaiklin, 2003; Kaptelinin & Nardi, 2006; Murphy & Rodriguez-Manzanares, 2007; Wikipedia, 2012). People may move between social contexts that impose different degrees of rigidity upon goals, the selection and use objects and tools, and the division of labor between actors. This complex web of interactions is depicted in Figure 1, below: AN OVERVIEW OF ACTIVITY THEORY Figure 1: Interactions in Activity Theory (Bury, 2012) Another concept that emerged alongside Activity Theory is Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development, which describes what individuals are capable and willing to do to attain desired goals (Chaiklin, 2003; Kaptelinin & Nardi, 2006). The zone of proximal development describes the gaps between what learners are capable of doing on their own and what they can achieve with the assistance of significant others such as teachers, tutors, coaches or peers (Chaiklin, 2003; Kaptelinin & Nardi, 2006; Koole, 2009; Wikipedia, 2012). The zone of proximal development illustrates that collaboration increases willingness and ability to learn, which in turn has a positive effect upon what the individual can do alone. Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development is depicted in Figure 2, below: 4 AN OVERVIEW OF ACTIVITY THEORY Figure 2: Vygotsky's zone of proximal development Activity Theory is a descriptive theory of human psychology and interaction (Wikipedia, 2012). However, it is congruent with, and foundational to, a number of prominent theories that inform distance education practice. Activity Theory in Context Activity Theory first emerged in the 1920s and 1930s from the work of Leontiev, Rubinstein and Vygotsky, who were dissatisfied with behaviorist psychology (Ballantyne, 2004; Russell, 2001; Wikipedia, 2012). However, its most widely recognized form stems from the work of Engeström beginning in the 1980s (Wikipedia, 2012). It has been applied to a wide range of social sciences, including human-computer interaction and teaching and learning (Atwell, 2012; Chaiklin, 2003; Impedovo, 2011; Kaptelinin & Nardi, 2006; Koole, 2009; Kuuti, 1995; Murphy & Rodriguez-Manzanares, 2007; Russell, 2001; Sharples et al., 2011). While Activity Theory contradicts behaviorist approaches, it is congruent with, and foundational to, such prominent learning theories as constructivism, connectivism, and Transactional Distance Theory. 5 AN OVERVIEW OF ACTIVITY THEORY 6 Constructivism focuses on how learners experience concepts or skills first hand, and then construct personally relevant meaning (Hover, 1996; Learning Theories.com, 2012). This is in keeping with the concept of actors learning by using tools and social rules to interact with objects. Connectivism draws strong parallels to Activity Theory, in that it describes knowledge and information as existing within systems constructed based on communal rules and with which learners must interact to forge connections based upon their own needs and contexts (Downes, 2012; Siemens, 2004). Activity Theory is also congruent with Moore’s (1989, 1991) Transactional Distance Theory, which focuses on the physical, psychological and knowledge differences between learners, significant others and content. Reducing transactional distance between learners and significant others is similar to fluency in the social rules described by Activity Theory. Such fluency enables communal interaction with objects (Chaiklin, 2003; Kaptelinin & Nardi, 2006), thus, the more easily actors are able to reach their goals. In Transactional Distance Theory, the less transactional distance there is between learners and significant others, the more easily they are able to interact to reduce the transactional distance between themselves and the learning content. Influence on Instruction Activity Theory can be used to inform instructional design decisions about the use of tools and the design of learner activity and interaction. Impedovo (2011) notes that learning is “always mediated” (p. 105) as learners attempt to make sense of the world around them, and Activity Theory can help understand both the affordances and limitations of mediating tools (Atwell, 2009; Impedovo, 2011; Sharples et al., 2011). For instance, Koole (2009) draws heavily AN OVERVIEW OF ACTIVITY THEORY 7 upon Activity Theory and the zone of proximal development in her Framework for the Rational Analysis of Mobile Education (FRAME), to describe how tools (mobile devices) facilitate requisite social and content interaction for physically remote learners. Instructional designers in any distance learning context must consider whether new tools increase the range of possible social and content interactions or if they force unreasonable constraints upon learners that limit their perceptions (Atwell, 2009; Impedovo, 2011; Sharples et al., 2011). Activity Theory can also help when making decisions that will affect the impact of community context. In formal educational settings such as K12 schools or campus-based postsecondary institutions there are very rigid norms of social interaction, division of labor, and use of tools (Atwell, 2009). These rules may serve to effectively scaffold the mastery of learning strategies and content, but they may also constrain the creative application of tools and social interaction. By considering the teachings of Activity Theory, instructional designers can push for the transformation of community rules that impose undue constraints. This is especially true in distance and mobile education, where considerable efforts remain underway to determine the most effective ways to employ technological tools and structure learning interactions (Russell, 2001). Resources for Further Study Useful links to more information about Activity Theory and the zone of proximal development, and their application in teaching, learning, distance and mobile education, can be found at https://landing.athabascau.ca/pages/view/197318/activity-theory-in-distance-education AN OVERVIEW OF ACTIVITY THEORY 8 References Atwell, G. (2009, December 21). Vygotsky, Activity Theory and the use of tools for formal and informal learning. [Web log comment]. Retrieved from http://www.pontydysgu.org/2009/12/vygotsky-activity-theory-and-the-use-of-tools-forformal-and-informal-learning/ Ballantyne, P. (2004). Leontiev’s activity theory approach to psychology: Activity as the “molar unit of life” and his “levels of psyche.” Retrieved from http://www.igs.net/~pballan/AT.htm Chaiklin, S. (2003). The zone of proximal development in Vygotsky’s analysis of learning and instruction. Retrieved from http://people.ucsc.edu/~gwells/Files/Courses_Folder/documents/chaiklin.zpd.pdf Downes, S. (2012). Connectivism and connective knowledge: Essays on meaning and learning networks. Retrieved from http://www.downes.ca/files/Connective_Knowledge19May2012.pdf Hoover, W. (1996). The practice implications of constructivism. SEDL Letter, 9(3). Retrieved from http://www.sedl.org/pubs/sedletter/v09n03/practice.html Impedovo M. A. (2011). Mobile learning and Activity Theory. Journal of e-Learning and Knowledge Society, 7(2), 103-109. Retrieved from http://jelks.maieutiche.economia.unitn.it/index.php/Je-LKS_EN/article/viewFile/525/530 Kaptelinin, V., & Nardi, B. (2006). Acting with technology: Activity theory and interaction design. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. AN OVERVIEW OF ACTIVITY THEORY 9 Koole, M. L., (2009). A model for framing mobile learning. In M. Ally (Ed.), Mobile learning: Transforming the delivery of education and training, 25-47. Edmonton, AB: AU Press. Retrieved from http://www.aupress.ca/index.php/books/120155 Kuutti, K. (1995). Activity Theory as a potential framework for human computer interaction research. In B. Nardi (Ed.), Context and consciousness: Activity Theory and human computer interaction (pp. 17-44). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Learning Theories.com (2012). Constructivism. Retrieved from http://www.learningtheories.com/constructivism.html Moore, M. (1989). Three types of interaction. The American Journal of Distance Education, 3(2), 1-6. Moore, M. (1991). Editorial: Distance education theory. The American Journal of Distance Education, 5(3), 1-6. Retrieved from http://www.ajde.com/Contents/vol5_3.htm#editotial Murphy, E., & Rodriguez-Manzanares, M. (2007). An Activity Theory perspective on e-teaching in a virtual high school classroom. Proceedings of the 10th IASTED international conference: Computers and advanced technology in education, 121-126. Russell, D. (2001). Looking beyond the interface: Activity theory and distributed learning. In Lea, M. (Ed.), Understanding distributed learning, 64-82. London, England: Routledge. AN OVERVIEW OF ACTIVITY THEORY Sharples, M., Taylor, J., & Vavoula, G. (2005). Towards a theory of mobile learning. Paper presented at the 4th Annual World Conference on Mobile and Contextual Learning (mLearn 2005), Cape Town, South Africa. Retrieved from http://www.mlearn.org/mlearn2005/CD/papers/Sharples%20Theory%20of%20Mobile.pdf Siemens, G. (2004). Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. Retrieved from http://www.elearnspace.org/Articles/connectivism.htm Wikipedia (2012, November 12). Activity theory. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Activity_theory 10