Discussion Section Notes (Thursday Sept 26

advertisement

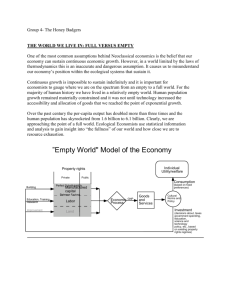

Exercise 2 The following questions should be answered in about ten or less sentences each. They should be ready for discussion the week beginning 23 September. 1. Try to explain Walras’ Law of Markets. Walras’ Law is the assumption that an economy will be at “full employment” because there cannot be a general surplus of production or supply. If there is a surplus in any commodity, its price will fall, leading to a reduction in supply and an increase in the quantity consumed. On the other hand, a surplus in one product implies excess demand for another, leading to price increases and reduced consumption there. …if there is excess demand, or short supply, in any particular market then there will also be a shortage, or excess, respectively, in another market. If producers work in order to consume, then the sum of excess demands and supplies over all the markets must equal zero regardless of whether all markets are in (general) equilibrium. In this case, if prices move freely, then these excesses and shortages will lead to equilibrating price changes that will eventually balance supply and demand for the entire economy; products in short supply will be bid up in price, reducing the amount demanded and increasing the quantity supplied, and the reverse will happen to products in excess supply. These price changes will continue until there is a balance of the quantity supplied and the quantity demanded at the market price in all markets. At “Walrasian equilibrium,” there will be full employment: the amount of every good that is produced will be consumed and everything that consumers want to buy will be produced. At these prices and quantities, every producer and consumer is as well-off as is possible given society’s resources and technology and their own tastes or preferences. 2. What is the Keynsian criticism of neoclassical economic theory? Keynes argued that macroeconomic outcomes, or the aggregate level of employment and output in an economy, cannot be explained by individual preferences. Instead, Keynes came to argue that aggregate, macroeconomic behavior, was driven by the behavior of social groups and social conditions that cannot be reduced to individual motivations. Instead of grounding his macroeconomics on individual motivation, Keynes argued that social outcomes and collective behavior reflect group behavior and dynamics independent of any individual volition. By rejecting the idea that individual choices determine social outcomes, Keynes denied that there was necessarily any rational or efficient process behind aggregate behavior. Instead, macroeconomic outcomes, Keynes argues, are shaped by irrational processes as likely to lead to inadequate levels of investment, high unemployment, and an unfair distribution of income as to adequate investment, full employment and a fair distribution of income. Irrational behavior in groups: Individuals behave differently because of group dynamics – a large group of individuals becomes a crowd, and even a mob. 3. In what way is capitalism a break from the production for consumption idea of Smith? Capitalist’s consumption is not tied to their production. They may but need not consume anything of what they produce and they do not hire workers to produce things for their consumption. Instead, they produce to make a profit and hire workers for this end. Smith explicitly described a world “[i]n that original state of things, which precedes both the appropriation of land and the accumulation of stock,” where all production is for use, for consumption, and “the whole produce of labour belongs to the labourer” (Wealth of Nations I.8.2). In this state, exchange is conducted either as barter, one commodity for another (C-C’) or with the use of money but only to facilitate barter (C-M-C’). All production (of C), however, ends with consumption, either of the original C or of an equivalent C’. Capitalists begin with money (M) and end with money (M’); if they are successful capitalists, M’>M the difference being profit. They use their money to hire workers for a set amount of time ( C ) during which they command the workers to produce commodities (C’) worth more than the workers’ wages. 4. In what way is capitalism egalitarian? Socially and politically, capitalism was ultimately incompatible with both feudalism and slavery because the anonymity of capitalist markets upholds the value and merit of labor against those who would claim a right to live off of the work of others on the basis of their birth. Against the pretensions of landed aristocrats and other gentlemen, the urban bourgeoisie and their allies among rural farmers and gentry upheld a social theory that ennobled work and those who labor. Against the “divine right of kings” and the claims of aristocrats and slave-owners that they were entitled to their wealth and power by virtue of birth, rural and urban capitalists campaigned under the banner of the “labor theory of value” to claim a larger share of society’s wealth and social and political status. By reducing all labor power to a common level as a commodity, and valuing all according to their power over commodities, capitalism has been a great egalitarian force. Viewing capitalism as a system of commodity exchange, Marx and many of his followers accept the claim by capitalism’s defenders that capitalism itself treats all equally without regard for religion, race, gender. (pg51-54) 5. What is marginal analysis? Marginal analysis has played a central role in economic theory since the late-19th century. By “marginal,” economists mean a small addition or reduction in the quantity of a particular good. Marginal analysis is a type of analysis that focuses on the impact of behavior on the margin, or the last unit of action. For example, each worker and each unit of capital (whatever that is!) is paid its “marginal product,” an amount equal to the change in output due to its presence in the production process. Ever-present in economic theory today, marginal analysis is fundamentally rooted in methodological individualism because it associates economic outcomes with discrete changes in individual inputs or consumer goods. Marginal analysis, therefore, is deliberately undertaken without regard for social context. 6. How does the marginal approach differ from the social institutions approach? Institutions- Social arrangements that act as constraints on individual behavior Social Institutions- A particular type of social fact where there are formal rules governing behavior. Ex. Norms, customs, laws, practices, patterns of behavior, etc. By ignoring social institutions, by grounding economics in what they assume to be universal motives of individuals, neoclassical economists have developed a theory that they claim can be applied universally, to different times and places. Neoclassical economists regularly apply their models to countries throughout the world, caring little and, often, knowing even less of any country’s particular political situation, its history, or its social structure. Neoclassicists have been criticized for ignoring history and social institutions; but their theory is powerful and can be applied universally because these are irrelevant in their models. Clark’s theory appears to be free of force or power because it makes distribution the result of universal forces; without force or power, there can be no exploitation. Because it is grounded in the actions of individuals, the neoclassical system suggests that we do, indeed, live in the “best of all possible worlds”. The neoclassical approach makes life easy for economists: there are no messy histories to be studied, no social structures to be analyzed. But there is also a politics here. By grounding their theory in terms of individual’s rational behavior, neoclassicists treat individuals as the source of all good and society as necessarily unproductive, adding nothing to the good produced by individual action. They believe that social institutions have no independent economic impact because wherever they interfere with individuals’ maximizing behavior they will be replaced by other institutions that will better facilitate individuals. Social institutions have no independent standing, they are epiphenomena, secondary manifestations of underlying causes rooted in the drive of individuals to maximize their welfare. Once people identify inefficient institutions, bad laws or social mores that lower income and raise transaction costs, they will replace them with better, efficient, institutions. Once social institutions have been dismissed, the fundamentally conservative program of neoclassical theory becomes clear. If individuals know best what is good for them, then society can add nothing to the work of individuals except to get out of the way and the best social policy places the fewest social restraints on individual maximization. 2 Neoclassical economists use an old joke to illustrate this efficient market hypothesis , or their concept of how rational behavior leads to social efficiency. Walking with an economics professor, an undergraduate bent for a $20 bill on the sidewalk only to be held back by the professor who assured her that the bill is a mirage because if it were real someone else would have picked it up already. This seems not only absurd in the example, but contradicts reality. Take wage differences within the US as an example. Within the United States, there are large gains to be made from even short moves. Among states in the United States, income is twice as high in Connecticut as in Mississippi, and over 50% higher in Maryland than in adjacent West Virginia. How do we explain why people remain poor in the truly wretched Dakotas rather than raise their incomes by moving east or west? Reference: Friedman, Microeconomics.Preface and chs 1 - 3.