The Elgin Marbles

advertisement

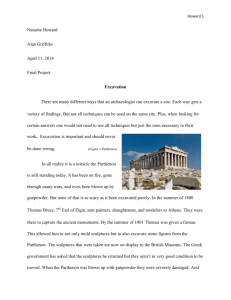

Becca Drustrup MST 503 The Elgin Marbles Controversy The Elgin Marbles is a collection of ancient Greek objects from Athens that was acquired by Lord Thomas Elgin during his time as an ambassador to the Ottoman court of the Sultan of Istanbul between 1799 and 1803. The collection consists of “sculptures from the Parthenon, roughly half of what now survives: 247 feet of the original 524 feet of frieze; 15 of 92 metopes; 17 figures from the pediments, and various other pieces of architecture. It also includes objects from other buildings on the Acropolis: the Erechtheion, the Propylaia, and the Temple of Athena Nike” (britishmuseum.org). The marbles later were moved to London and have been on permanent public display in the British Museum since 1817, free of charge. There the marbles are seen by a world audience and have been actively studied and researched to promote a worldwide understanding of ancient Greek culture. The controversy of the Elgin Marbles concerns the removal of these objects and whether or not they should be returned to Athens. Lord Elgin had a great passion for antiquities and wanted to gather Ancient Greek art to use as models for artistic practice in Britain. He bribed local Ottoman authorities into permitting the removal of about half of the Parthenon frieze, fifteen metopes, and seventeen pedimental fragments (Venieri). Elgin first used the collection to decorate his mansion in Scotland and then later sold them to the British Museum as an attempt to pay off his debts. The objects were bought by Great Britain in 1816 for £35,000, considerably below their cost to Elgin (estimated at £75,000), and placed in the British Museum (St. Clair). Currently, the marbles are located in the Duveen Gallery at the British Museum. When Elgin’s men removed the objects, the Parthenon was in a fragile and decrepit state. From the fifth century BC to the 17th century AD, the building was in continuous use. “It was built as a Greek temple, was later converted into a Christian church, and finally (with the coming of Turkish rule over Greece in the 15th century) it was turned into a mosque” (Beard). In 1687, fighting broke out between the Venetians and Turks, and a Venetian cannonball hit the Parthenon, consequently ruining the building. By 1800 a small replacement mosque had been build inside the Parthenon, while the outer part of the building was left to ruin. Local Athenians had used the Parthenon as a quarry and reused a large amount of the original sculpture and building pieces for either local housing or cement. There were also high numbers of travellers and antiquarians from northern Europe who took objects from the Parthenon, such as the Elgin marbles collection. The Acropolis hill houses famous monuments of the fifth century BC, including the Parthenon, the small temple of Victory, the Erechtheum, and another shrine of Athena. In the 1800s, the Parthenon stood in the middle of the village surrounded by houses and gardens, as well as Byzantine, medieval and Renaissance remains. According to Mary Beard “it is quite wrong to imagine Elgin removing works of art from the equivalent of a modern archaeological site- it was more of a seedy shanty town” (Beard). After the 1830s the hill was stripped to its bedrock, with the monuments preserved or reconstructed, to serve as a symbol of the nation’s history. It is a common belief that the Parthenon could be better appreciated if it could be seen close to the sculptures that once adorned it, which is why the demand for the return of the marbles continues to be discussed. The removal of these objects was controversial from the beginning. “Even before all the sculptures - soon known as the Elgin Marbles - went on display in London, Lord Byron attacked Elgin in stinging verses, lamenting (in ‘Childe Harold's Pilgrimage’) how the antiquities of Greece had been ‘defac’d by British hands’” (Beard). Where Lord Byron criticized the acquisition of these objects, others supported it. John Keats wrote a sonnet about “seeing the Elgin Marbles” in the British Museum and in Germany, JW Goethe believed that the acquisition was the “beginning of a new age for Great Art” (Beard). Elgin took the marbles in an effort to bring artistic innovation to Britain. It does not appear he was being malicious or wanting to take away objects that represented Athenian history and culture. There is no doubt that he saved the objects from further damage, from looters and/or the elements. Some argue in Elgin’s favour that he housed and took care of the objects, while Athenians let their history potentially go to ruin. However, in prising out some of the pieces that were still attached to the Parthenon, Elgin’s agents inflicted additional damage to the already fragile building. While the objects were on display, they suffered from 19th century pollution, which persisted until the mid-20th century (St. Clair). Greek conservators have stated that the objects have been irrevocably damaged by previous cleaning methods employed by British Museum staff. Efforts were made to clean the marbles in the mid-1850s as well as the late 1930s. The latter cleaning effort was fully financed by Lord Duveen, who later built the wing where the marbles are currently held. Such controversies can involve politics, where policies may be created to protect institutions and their collections. The British Museum Act of 1963 consequently forbids the British Museum from disposing its holdings, except in a small number of special circumstances. The Act states that the Elgin Marbles, Benin Bronzes and its Nazi-looted artworks are to remain at the Museum. In 2009, however, the Holocaust (Stolen Art) Restitution Act was created. The act now gives institutions in England and Scotland the power to return art stolen during the Nazi era. In an effort to have an amicable relationship with Greece, Britain offered a three-month loan of the marbles to the Acropolis Museum on condition that Greece recognizes Britain’s ownership. Greece countered that Britain could borrow any masterpiece it wished from Greece if it relinquished ownership of the Parthenon sculptures. Since Britain wants to claim ownership of the collection, they will not hand over the marbles. In the debate it has been said that Athens did not have an adequate place to house the Elgin Marbles. However, in 2009 Athens built the New Acropolis Museum, which is a $200 million, 226,000-squarefoot, state of the art rebuttal to that argument. The Acropolis, designed by Swiss architect Bernard Tschumi, includes weathered original sculptures from the Parthenon, as well as plaster casts of Elgin’s marbles to “complete” the collection. “The clash between original copies makes a not-subtle pitch for the return of the marbles. Greece’s culture minister, Antonis Samaras said what Greek officials have been saying for decades: that the Parthenon sculptures broken up are like a family portrait with ‘loved ones missing’” (Kimmelman). Although the Elgin marbles are the most often debated about, they are not the only surviving Parthenon sculptures in the world. Such sculptures are found in museums across Europe. The majority of these are roughly equally divided between Athens and London, but others are held in museums such as the Louvre and the Vatican. Why is it that the Elgin collection must go back to Athens when these other museums also house Parthenon objects? True, the Elgin marbles are a larger collection and have generated more publicity, but why is it that the Grecian government is making an effort to reclaim only these objects? It is understandable that Athens wants what was taken from them, but returning the Elgin marbles could spark a bigger controversy in who actually owns history. Many important points have been raised in this controversy and will most likely continue to be debated. For example, would all looted material have to be returned to its original owner? During World War II, Nazis plundered priceless works of art, and now these objects are displayed throughout the world. If the Elgin marbles are returned to Athens, will this be the beginning of repatriating all displaced objects to their homeland? Many questions come to mind when thinking of this ethical concept, such as: Is it right to remove objects from the museums who have been caring for and storing them all of these years? Who are the rightful owners of objects that were taken during war conflicts? I have known about the Elgin marbles debate for several years and have had conflicting opinions. I believe in the education of cultures, their history and objects. Furthermore, I believe in museums housing these historical objects. People go to museums to see objects from around the world that they will most likely not see in their neighborhoods. What better way to learn about ancient Greece than to go to the museum and admire the Grecian objects they house? Having a collection of objects from around the world helps visitors learn about various cultures without having to travel across the globe. For Athens to reclaim the Parthenon sculptures would be a great accomplishment as they would also be reclaiming a part of their past. They feel drawn to these objects as they represent the thousands of years their people have been in existence. I recognize that the sculptures are Greek and originally came from the Parthenon, however the British Museum has cared for and built a gallery specifically for the purpose of exhibiting these objects. Even though I can understand both sides, I believe that this debate will continue as both sides fight passionately for the right to call themselves the true owner of the Elgin marbles. Bibliography Beard, Mary. "Lord Elgin -Saviour or Vandal?" BBC News. BBC. Web. 17 Feb. 2011. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/greeks/parthenon_debate_01.shtml Kimmelman, Michael. "Elgin Marble Argument in a New Light." New York Times. 23 Jun 2009. Web. 27 Mar. 2013. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/24/arts/design/24abroad.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0 St. Clair, William. Lord Elgin & The Marbles: The Controversial History of the Parthenon Sculptures. Third edition. London: Oxford University Press, 1998 (originally, 1967). Venieri, Ioanna. "Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Tourism | Acropolis of Athens." Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Tourism | Acropolis of Athens. Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs, Cultures and Sports, 2012. Web. http://odysseus.culture.gr/h/3/eh351.jsp?obj_id=2384 "What Are the 'Elgin Marbles'?" The British Museum. British Museum, 2013. Web. http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/articles/w/what_are_the_elgin_marbles .aspx