File - keep practising!

A video by The British Museum / the Parthenon Marbles

Bonnie Greer / trustee: The Parthenon sculptures are one of the reasons that I’m really proud to be a trustee at the British Museum. I really believe that they belong here. You know I’ve been trying to figure out why I think that way.

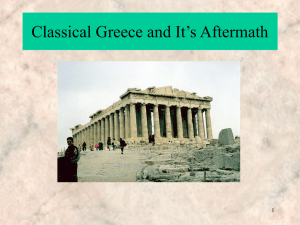

The Parthenon sculptures were brought from the Acropolis in Athens by Lord Elgin to Britain at the start of the 19 th century. Originally they were placed up on the side of the great Athenian temple. For me, these wonderful sculptures raise the bar artistically for everything that came since.

As a playwright I love the kneaded power of this. I love its vigour, you could write speech bubbles. A thousand people could have speeches coming out of this guy’s mouth and you would never exhaust what the relationships to each other is. They’re absolutely magnificent. They’re so beautiful you know sometimes when I look at them, they really seem like they’re alive.

Ian Jenkins / Curator: flesh and flowing drapery.

It’s the ultimate in alchemy. You take cold hard marble and you turn it into warm

Visitors: Well, first of all, this is the first time for me that I see the place and I’m very impressed and I think they’re simply perfect. I mean they are so simple but at the same time they have everything /

Probably the most beautiful things, sculptures which I’ve ever seen, really / To be able to come into the city of London, just go back to a time when such art like this was created is very exciting.

Ian Jenkins / Curator: They’ve become great works of art because they have been taken from the building placed in front of the spectator and there is another body of sculpture from the Parthenon and that is going to be brought down to us as part of the great conservation programme that our colleagues in Greece are undertaking.

The British Museum is a centre of the Parthenon studies and actively researches its sculptures. It works with scholars from all around the world including colleagues in Athens. With them we share a desire for better understanding of what the sculptures meant to people in antiquity and indeed what the sculptures looked like before so many of them were broken or lost. Computer graphics can help here especially in restoring missing parts, offering alternative restoration and even reconstructing the colours that may once have been applied to the marbles

Bonnie Greer / trustee: At the British Museum you can see the marbles next to earlier cultures that influenced the Greeks. You know it’s amazing to think that when the Greeks were learning and admiring from these objects they were as far away from the Egyptians as we are from the Greeks today. But just as interesting is the influence they wielded over those that came after. Walk around the Roman gallery and you can see how slavishly they copied the Greeks they so admired. 1,500 years later, Renaissance artists like Michelangelo were inspired by these

Roman copies. As you can see in the Museum’s prints and drawings room.

Ian Jenkins / Curator: A drawing like this study for the creation of Adam for the Sistine Chapel ceiling makes marvellous comparison with the reclining river-god of the west pediment of the Parthenon and we can see him refitting the human form to create his ideal version.

Bonnie Greer / trustee: But moving on to the Indian Galleries, other more surprising connections can be made. This really reminds me of the sculptures and Greek art in general because, you know, look at the flow here, the drapery flows and the footstands and this kind of heroic arms outstretched and the shoulders and …it’s very Greek, isn’t it?

Sona Datta / curator: It’s very interesting you should say that because this sculpture comes from about the 2nd century AD from a place in the North Western frontier which is today Pakistan and where the remnants of

Alexander’s army penetrated India and so they were trying to be absorbed into the majority faith. So what do you do how do you make that easier? You dress the Budha up to look like a Greek.

Bonnie Greer / trustee: other times.

Throughout the Museum you can find exciting parallels with other cultures and