File - Anne W. Anderson

advertisement

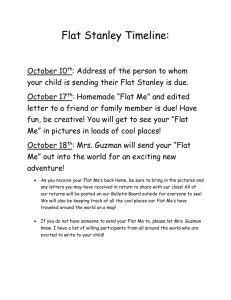

Anderson and Powell 1 Anne W. Anderson and Rebecca L. Powell Professor Jenifer J. Schneider LAE 7747 Literary Theory 14 March 2013 The World is Flat, Stanley: Globalization and Absurdity in an Early-Reader Chapter Book Thomas Friedman’s The World is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-first Century, claims ten events or forces occurred during the latter half of the twentieth century that contributed toward leveling the world’s economic playing field at the beginning of the twentyfirst century, moving it from an era of nationalism into one of globalization. None of Friedman’s ten forces, however, includes a globe-trotting paper figure first introduced in a 1964 early-reader chapter book, Flat Stanley. While critics argue over Friedman’s theories and conclusions, few people dispute the increasing interaction among peoples, cultures, nations, and economies. Still, few scholars have considered the influence of children’s literature, a segment of both the literary and the education worlds, has had on this trend towards globalization. For instance, the original Flat Stanley writing project was conceived by a third-grade Canadian teacher, and Flat Stanley eventually connected children around the world with each other. Given that countless parents, grandparents, and other adult relatives and friends facilitated the mailing of Flat Stanley, that early, snail-mail-powered social network involved and included more than just children. In this paper, we discuss Jeff Brown’s original Flat Stanley book and sequels, Flat Stanley’s subsequent transformation thirty years later into a classroom pen-pal-with-a- twist writing project, the 21st century Flat Stanley books that take readers around the world with Anderson and Powell 2 Stanley and friends, and the Flat Stanley Project’s Web site and iPhone software application. How do they present the world and other cultures? And how is that presentation mitigated by the discourse of absurdity found throughout the series? Methods We approached Flat Stanley from two perspectives, as one of us is a former elementary school teacher currently working as a liaison between a school district and a university college of education while the other is a journalist and author of children’s stories. Both of us came to this project as student scholars with an interest in theorizing early-reader chapter books. To begin our research, we read each of the books in the Flat Stanley series for a sense of the whole. After reading, we met and discussed the original Flat Stanley paratext, illustrations, and text. We created a chart to further explore each book’s cover illustration, setting, plot, depiction of the main character in a new culture, and facts about the various places visited (Appendix A). Specifically, we studied characters’ responses to various cultures, preconceptions related to society other than their own, and the use of absurdity throughout the text. Our search also included a visit to the titular character’s digital life at www.flatstanley.com. After studying the books, we reviewed the literature related to discourses in the text, the notion of ethnocentricity that is characteristic within the text, and the literary device of absurdity, which permeates the series. Theoretical Literature Review An Understanding of Discourse John Stephens, in his 1992 work, Language and Ideology in Children’s Fiction, quotes Guy Cook’s definition of discourse as “stretches of language perceived to be meaningful, Anderson and Powell 3 unified, and purposive” (11) then distinguishes Cook’s linguistic discourse from his own definition of narratological discourse as “the means by which a story and it significance are communicated” (11). Language, of course, can be communicated verbally through speech; visually by text, pictures, gestures, and physical positioning (body language); and through symbolic sounds other than words (some forms of drumming, for instance). Specifically, Stephens notes, “[P]ictures, like verbal texts, can be discussed in terms of their discourse, story and significance since they, too, have a ‘what’ and a ‘how’ made up of represented objects and a mode or style of representation” (162). In explaining the narratological understanding of discourse, Stephens suggests “narrative consists of three interlocked components, a discourse [presumably the discourse of the language in which the text is written], a ‘story’ ...and a significance....” (12). The story is what the reader ingests through the physical act of taking in text and is what the reader can regurgitate if prompted to do so by the question, “What was that story about?” The significance, Stephens writes, requires a “secondary reading level” made up of “emotional space which the reader can inhabit largely on his or her own terms, matching the emotion from personal experience” and containing the “thematic purposes and functions, whether deliberately...or implicitly” (14). Stephens calls the “move to the level of significance...mandatory” based on cultural expectations (drilled into us, perhaps, by generations of English teachers?) and, more importantly, by the “impact...of such top-down discoursal elements as social practice, generic relationships and inscribed point of view” (14). Early-reader chapter books such as the Flat Stanley series contain discourses of text and pictures and are told in narrative, or story, form. In terms of significance, we found two discursive elements of significance in the Flat Stanley series, the elements of ethnocentricity and Anderson and Powell 4 of absurdity. Each of these elements, what Stephens would call “macro-discourses” is conveyed through language, illustrations, and the interaction between the two, what Stephens would call “micro-discourses” (12-14). In order to understand both types of discourse, readers must be, as Stephens terms it, “capable of bottom-up interpretation...be able to decode language in both small and large units, and be sensitive to how...micro-discourses and macro-discourses interact” (14). Two of those macro-discourses include ethnocentricity and absurdity, which we discuss next. The Discourse of Ethnocentricity As we considered how educators have used Flat Stanley to teach everything from how to address an envelope to global geography, we examined ethnocentricity through the discourses of the Flat Stanley series. Weil, writing in a 1993 Roeper Review article titled “Towards a Critical Multicultural Literacy: Advancing an Education for Liberation,” calls ethnocentricity “cultural encapsulation” and defines it as “the belief in the inherent superiority of one’s own group or culture” (n.p.). Such ethnocentricity may come from assumptions about a culture or from uncritical thinking about the culture. To pretend that we have no assumptions about a culture is wishful thinking. Donald Macedo, in his introduction to Paolo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed, writes, ”[T]he Assumption of a View from Nowhere is the projection of local values as neutrally universal ones, the globalizing of ethnocentric values, as Stam and Shohat put it” (24). In other words, in thinking that we are being culturally neutral, we are denying our own culture and its presumptions. Equally self-deceptive is the belief that one can passively accept media representations of other cultures. Weil terms such beliefs “borrowed thinking that is not rigorously or critically Anderson and Powell 5 examined, [which] often poses as our own thinking.... As [borrowed] thinking substitutes for critical reflective thinking, the uncritical mind looks for stereotypes and simplistic categories in which to conveniently place people, things, and places” (n.p.). Derrida addresses both types of ethnocentric thinking when he discusses the origins of ethnology, a branch of social science developed in the late nineteenth century. Derrida notes: “…ethnology could have been born as a science only at the moment when a decentering had come about: at the moment when European culture—and, in consequence, the history of metaphysics and its concepts—had been dislocated, driven from its locus, and forced to stop considering itself as the culture of reference. … Consequently, the ethnologist accepts into his discourse the premises of ethnocentrism at the very moment when he denounces them” (199). Derrida’s ideas bring to the forefront the question of decentering. Can readers, especially children, decenter-dislocate from their own culture-to examine the politics of difference and otherness? Does writing a letter and imagining oneself to be a caretaker for Flat Stanley allow the reader to create significance based on, as Stephens put it, personal experience and an understanding of literary theme and embedded ideology about other cultures? Essentially, as Derrida pointed out, any writing about a culture other than one’s own presumes a viewpoint of other as different. Even when writers discuss similarities, such discussions are within the context of implied differences. Some scholars feel such literature, even if not intentionally so, is condescending. Laubscher and Powell (2003), for instance, writing in the Harvard Educational Review, say of such constructions, “The visibly different are thus to be forever grateful that they have been let in [into the literary space], but know that they never truly belong....” (221). However, Laubscher and Powell also would not have us construct otherness as a false-positive. “We believe,” they write, “that richer learning is possible through attention to Anderson and Powell 6 such politics of difference, as opposed to add-on multiculturalism that “celebrates” exotic otherness as diversity” (221). But is it, possible, as Laubscher & Powell say, attend to politics of difference without first examining “otherness,” even exotic otherness? In the Flat Stanley series, Stanley visits other cultures and views them from his white, middle-class perspective, seeing them often as both exotic and as worthy of being celebrated. Exotic and worthy of being celebrated, however, does not always mean the cultures are accurately portrayed, as will be discussed in a later section of this paper. Debates continue over whether writers can write about cultures other than their own. Taken to one extreme, and allowing for freedom of the press and within the legal considerations of libel and slander, anyone could write about any other culture regardless of whether or not the depiction was accurate. Taken to another extreme, no one could ever write about anything other than his or her own personal experiences and could not even include depictions of other people in those experiences because to do so would be to portray them only from the author’s perspective. Yet one form of discourse routinely deflects and deflates other more caustic discourses: humor in all its various forms. What mitigates what might otherwise be construed as condescending ethnocentrism is the element of the absurd which permeates the Flat Stanley series and to which we now turn. A Discourse of Absurdity Humor as a discourse within literature--even children’s literature--seems to be seldom discussed. A review of indexes and tables of contents of several books [I will footnote this] found almost no mentions of either “humor” or “play.” Where play is listed, it often is discussed in terms of word play and refers to play’s definition as unimpeded movement. In this sense, Anderson and Powell 7 Derrida describes the field of play as “a field of infinite substitutions” (205). In other words, when we play with words we substitute one word with another to achieve a particular effect-alliteration, assonance, etc. Joseph Campbell, in his epic work The Hero with a Thousand Faces, devotes three pages (out of 400+ page book) to a discussion of humor within one Hindu myth. More recently, Brian Boyd’s 2009 book, On the Origin of Stories: Evolution, Cognition, and Fiction, lists one reference for “humor” in the index--a reference which takes the reader to a page discussing the “pleasure” readers derive from reading Dr. Seuss’s books...but which never actually uses the word “humor” (333). Perry Nodelman, in The Pleasures of Children’s Literature, lists the ability of a text to make the reader laugh as one of many “literary pleasures” (25) but does not discuss the discourse of humor itself. British psychologist Michael Apter, writing about his reversal theory of humor, suggests “all types of humor, while retaining certain essential features in common, fall into two basic...types,” which he calls “disclosure and distortion humor” (417). Whereas disclosure humor, according to Apter, relies on words and images often having double meanings, distortion humor takes a distinct identity with “certain real characteristics” which then “are varied imaginatively, or exaggerated, to the point that the identity is diminished through absurdity” (424). However, Apter cautions, “the term ‘distortion’ should not be taken to imply anything pejorative” (424) as “the original characteristics must continue alongside the new ones and both be clearly related to the same identity in a plausible way, thus creating a synergy” (424). As an example, Apter suggests nonsense rhymes derive their humor from “the nonsense [ words being] embedded in something sensible,” such as “rhyming lines, and a narrative that makes a certain kind of sense” (425). Reversal theory suggests that “there is indeed a fusion of opposites in all humor” (431). Apter gives the example of a Dilbert cartoon where “someone is told off for Anderson and Powell 8 wasting electricity by using bold print on his computer screen” (431). In some forms of humorous discourse, therefore, what is literally said is exaggerated to the point of absurdity and the meaning becomes reversed--it becomes the opposite of what was stated. Barbara Stern, writing in the Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, notes, “Both literature and advertising share similar goals of getting inside audiences’ heads and inspiring them to experience things in fresh, new ways. They also employ similar creative techniques to say things in ways other than by direct statements of fact....” (72). Stern analyzed a number of “literary tactics” (72) employed by advertisers, including the use of absurdity, which she says “disrupts conventional notions about meaning by questioning its very existence” (75). In particular, Stern writes, “Absurdist fiction rebels agains the beliefs and values of traditional western culture....” (76). Because the author of the text is not conveying information in a straightforward manner, but is instead presenting a story “in which characters behave irrationally, where causal sequences of events are illogical, and where incongruous juxtapositions of people and things occur” (76), the reader must, as Stephens put it, decode this macro-discourse in order to understand the intended meaning of the author and to be able to determine its significance in terms of literary theme and social implications. As Stern writes, “The burden of interpretation is on the interpreter....” (76).1 In reading Flat Stanley, then, we must bring to the series an understanding of the discourse of ethnocentrism, which postulates an inescapable absurdity in itself, and of the discourse of absurdity. 1 Interestingly, a 2000 study of the effects of absurdity in advertising suggests that “positive cognitive responses” produced by ads featuring absurdity were associated with increased brand recognition and increased positive response toward the brand (Arias-Bolzmann, Chakraborty, and Mowen, 2000, 44). Does this mean we respond positively to that which stimulates us intellectually? Anderson and Powell 9 Discussion of Process and Findings In this section, we apply the macro-discourses of ethnocentricity and absurdity to the Flat Stanley phenomenon. In order to better understand Flat Stanley’s influence over the past almost fifty years, we provide a brief history of the evolution of Flat Stanley. A Brief History of Flat Stanley The author of the original Flat Stanley, Jeff Brown, (1926-2003), wrote the first Flat Stanley book after his sons asked him one evening what would happen if a bulletin board fell on them during the night. He replied that they would not wake up because it would fall slowly, but when they did, they would probably be flat. From that witticism, he created stories at bedtime for his children about what life would be like if you were flat. Later, a friend of Brown’s suggested he publish the adventures. Brown wrote five other books between 1983 and 2003, which were illustrated by various artists, and which starred a no longer flat Stanley and his family. In the final book, Stanley, Flat Again, Stanley reverts to his flat state. Subsequently, in 1995, Dale Hubert, a third grade teacher in Ontario, Canada, began the Flat Stanley Project, which involved students creating their own Flat Stanley cut-out character, keeping a journal of Stanley’s adventures, and then mailing him to family and friends who were asked to continue Stanley’s odyssey before returning him to the original sender. FlatStanley.com, the Web site for the current Flat Stanley Project, describes the goal as being for students to engage in an “authentic literacy project,” to encourage letter writing, either through conventional mail or digitally, and to follow the characters on journeys around the world. Hubert’s idea caught on and Flat Stanley experienced a new generation of readers. In 2001, Hubert received the Prime Minister’s award for the Flat Stanley Project. Anderson and Powell 10 In 2010, Darren Haas created an application for Flat Stanley on the i-Phone. Through this application, students can create their own Flat Stanley characters, insert the characters into their photos, and share them with others through their phones. In addition, students may also track the travels of their characters. The Flatter World network consists of more than 4,500 schools in more than 88 countries, and includes a Facebook page. Ethnocentricity in the Original Story Ethnically, Flat Stanley and his family have always been portrayed as white, middle-class (Mr. Lambchop works in an office and wears a long-sleeved white shirt, suit pants, and tie; Mrs. Lambchop wears pearls, a sweater top, and a skirt), suburbians (they go downtown to the museum). However, while the text of the original Flat Stanley story has remained the same over the past forty years, the overall illustrations have changed at least three times, changes in which implies the locus of the ethnocentric perspective has shifted. Nowhere in the text is the Lambchop family explicitly described as being white or middle-class; in this sense, the illustrations convey more information than does the text. In this section, we first examine the 1964 illustrations by Tomi Ungerer and then the updated 2003 series’ illustrations by Scott Nash. Finally, we examine the illustrations by Macky Pamintuan, who provided visual continuity by reworking the illustrations for Jeff Brown’s books and did the original illustrations for the new 2009 Worldwide series. In the original 1964 Flat Stanley, illustrated by Tomi Ungerer, all the characters in these pen-and-ink drawings (colored?) all appear to be of Caucasian/European descent. The two Lambchop boys, Arthur and Stanley, appear to have light complexions and medium brown hair. Mrs. Lambchop is given a pinkish complexion while Mr. Lambchop and the boys have lighter complexions. Arthur and Stanley have rounded eyes and small rounded noses. The adults are Anderson and Powell 11 portrayed with longer, thinner noses. The doctor has a dark, walrus style mustache. The doctor is portrayed as an older male, with glasses, and round in stature. His nurse, on the other hand, appears younger and curvaceous, with long eyelashes, pursed lips, wearing a form-fitting uniform and a nurses cap. The police officers in this version were portrayed in caricature, with one having pudgy cheeks and the other a long, thin face. In constructing a middle-class, suburban lifestyle, Ungerer depicts Stanley’s bedroom as including a shelf full of toys typical of boys in the 1960’s (tools, a ball, a weapon, and a car). There is an airplane suspended from the ceiling. Stanley wears pajamas in his bed, which is depicted as having sheets, blanket, and pillow. Mr. Lambchop wears glasses and suspenders early in the morning, otherwise he and the others are dressed formally. When Mrs. Lambchop and Stanley go out for a walk, Mrs. Lambchop wears a fur-trimmed coat, gloves, and high heels. Stanley is dressed in a shirt and tie. In 2003, the illustrations in the Lambchop family books were updated by illustrator Scott Nash. Whereas Ungerer’s 1964 sketches were more complex in terms of details, such as the number of fingers on the characters’ hands and in terms of background details, Nash’s illustrations appear flatter and more cartoonish. Flat Stanley still is depicted as light-skinned, but now he has freckles and reddish hair. Mrs. Lambchop, Arthur, and Stanley are depicted with round faces, but Mr. Lambchop’s face is long and his hair is thin. Mr. Lambchop’s nose appears exaggerated in length and comes to a ski-slope point. Stanley, Arthur, and Mrs. Lambchop have noses that appear as small triangles. Perhaps because her face is round and her nose is the same as Stanley’s and Arthur’s, Mrs. Lambchop appears almost juvenile, with no cheeks and flat features. She appears heavier than in the original 1964 edition, especially in comparison to the adult men in the book. Scott Nash maintains the middle class suburban construction of the Anderson and Powell 12 Lambchop family, particularly through the clothing choices for Mr. Lambchop and Mrs. Lambchop. Mr. Lambchop is clothed, even on a trip to the park, in suit pants, a white, collared shirt, tie, and a sweater top. Mrs. Lambchop, while taking a walk, wears pearls. However, Stanley has changed from wearing a shirt and tie to a more casual v-neck, long sleeved sweater and pants. Arthur emulates his father by wearing a shirt and tie. The doctor, in Nash’s version, has changed from rounder to more slender, has more hair, and has a more well-trimmed mustache. The nurse is not seen, except for her well-manicured, pointy, and highly-polished fingernails. The policemen, though they appear somewhat amused by the activity of Mrs. Lambchop, are less caricatured and more life-like. The thieves, in the museum scene, appear elfish. Nash depicts the police chief as Black, broad, wearing glasses, a mustache, a toothy smile, and with tight curly, dark hair. When the Worldwide series began in 2009, Macky Pamintuan re-illustrated the original books. His depiction of the first Flat Stanley story reimagines the Lambchop family. The Lambchop’s faces all appear to be more angular and their bodies are thinner, perhaps reflecting a more recent emphasis on health consciousness and exercise. Stanley has gone from Nash’s lightskinned, round-faced, freckled, and red-headed boy to a darker skinned, brown-haired boy with an oval-shaped face, a pointed chin, and a more defined nose. Arthur’s face also is more defined and his hair is black. Mr. Lambchop has become broad-shouldered, lantern-jawed, and has more hair. Mrs. Lambchop is thinner, and has blonde hair. Dr. Dan, on the other hand, has aged. He now is balding, with a white fringe of hair, bushy white eyebrows and a bushy white mustache. His nurse still wears a skirt, but she is less curvaceous. Her hair appears to be pulled back and she wears sensible clogs. The policemen are not depicted, except for their shoes. The thieves are still caricatures, but are no longer elfish. The police chief is not depicted. It does not appear that Anderson and Powell 13 there are any other ethnicities represented. Mr.Lambchop’s and Arthur’s attire has become more casual when they are at home. Mrs. Lambchop wears a more form fitting dark skirt, with a white square or round neck shirt. In each of the three versions of the original Flat Stanley story, the overall visual depiction of the Lambchops as a white, middle-class, suburban family is maintained, despite obvious shifts in how ethnicity, masculinity, femininity, and age are portrayed and in what is considered appropriate dress for various occasions. The text emphasizes their cultural understanding of manners, particularly polite and grammatically correct speech and their cultural understanding of what constitutes healthy behavior. This then is the ethnocentric lens through which Stanley and his family view the rest of the world in their travels, a lens which would seem to predispose them to seeing the rest of the world in stereotypical fashion. However, just as Derrida noted, “…ethnology could have been born as a science only at the moment when a decentering had come about: at the moment when European culture—and, in consequence, the history of metaphysics and its concepts—had been dislocated, driven from its locus” (199) Stanley’s flatness has dislocated the Lambchop family’s center. People begin to make fun of Stanley and Mrs. Lambchop says, “It is wrong to dislike people for their shapes. Or their religion, for that matter, or the color of their skin” (56). Considering this was written in 1964, Jeff Brown’s text could be perceived as an explicitly inserted political ideology. Given Derrida’s idea that one can only perceive ethnocentricity through an ethnocentric lens, Stanley’s response to his mother, “only maybe it’s impossible for everybody to like everybody” (57), is more true than we are willing to admit. Yet, there is a difference between respecting others and liking others. So the question becomes, to what extent does the worldwide series promote a Anderson and Powell 14 respect for other cultures? Before we examine that question, we turn to the discourse of absurdity as found in the original Flat Stanley story. Absurdity in the Original Story Shklosky (1917) suggests our daily lives become so habitual that we no longer perceive the reality of what we are experiencing (in Rice and Waugh, 2010). Habitual tasks and words lose their conscious immediacy through “overautomatization” (49) and become, as it were, indistinct parts of the formula of life. Unless something comes along to help us “recover the sensation of life,” as Shklosky says is the role of art (50), we become “devour[ed]” (49) by habitualization—we lose something of ourselves. Art accomplishes this by “defamiliariz[ing]” (p. 50) the familiar; and Shklosky gives as an example Tolstoy’s helping the reader see something as if for the first time by describing it without naming it (50). Trauma also can jolt us from our familiar routines and perceptions. But what happens when art explicitly names, describes, and takes trauma to ridiculous lengths? In Flat Stanley: His original Adventure!, Jeff Brown invites readers to explore the familiar world from the unfamiliar perspective of a child, Stanley Lambchop, flattened by a fallen bulletin board to a thickness of half an inch. Life goes on as usual, more or less, but Brown helps readers imagine what it would be like to live in a notquite two-dimensional world: Stanley slips under locked doors, mails himself to a cousin in California to avoid paying airfare, and becomes a kite flying in the air. Recalling Stern’s depiction of absurdity as a story “in which characters behave irrationally, where causal sequences of events are illogical, and where incongruous juxtapositions of people and things occur,” therefore, a reader able to decode the macrodiscourse might conclude the original premise of Flat Stanley is absurd in the sense that it presents an illogical occurrence as being logical. Additionally, the characters react irrationally. Anderson and Powell 15 When Arthur tries to alert his parents to Stanley’s predicament, the parents are more concerned with “politeness and careful speech” than with what Arthur is trying to say (2). Stanley is portrayed as unharmed by the fallen bulletin board, described as “enormous” (3), which takes both Mr. and Mrs. Lambchop to lift it and was heavy enough to flatten him but which did so without awakening him. However, instead of rushing off to seek medical attention for Stanley, Mr. Lambchop suggests the family have breakfast first. Throughout the story, incongruities also occur. When Mrs. Lambchop loses her ring down a storm grate, Stanley removes his shoe laces, ties them together and ties one end to the back of his belt. Then he has his mother lower him between the bars to search the shaft. In a scene reminiscent of a Laurel and Hardy sketch, two police officers come along as she is standing over the grate, shoelace in hand, and with Stanley not visible. The officers, of course, see an absurd scene; when she tells them her son is at the other end of the shoelace, they react logically by saying she is “cuckoo” (14). However, when Stanley reappears, the officers do not see anything out of the ordinary with Stanley’s flatness or with his being used to retrieve the ring in such a manner. Instead, they apologize for their rudeness. The premise of the original story is absurd, and both the visual and the textual elements of the story continue to convey absurdity. How does this absurdity mitigate the ethnocentric lens through which the Lambchop family views the world in the Worldwide Adventure series? Ethnocentricity and the Worldwide Adventure Series Beginning in 2009, Flat Stanley began traveling the world, not just by being mailed as a cutout character but through the pages of a new series of books called Flat Stanley’s Worldwide Adventures. Written by, to date, two different authors, these new books retain as characters the original Lambchop family, as well as Dr. Dan and Mr. O. Jay Dart, the director of the Famous Anderson and Powell 16 Museum of Art. Each book continues signature text begun in the original story--at some point either Arthur or Stanley will say, “Hey!” and will be reminded that “Hay is for horses, not people”--and each book reiterates the importance of polite behavior, proper grammar, and appropriate hygiene--each defined by white, middle-class values and each exaggerated to the point of absurdity. Sometimes, as in The Great Egyptian Grave Robbery, the second book in the series, Stanley travels alone (usually via mailer envelope); other times, the family travels together, as in the first book in the series, The Mount Rushmore Calamity. In each book, Arthur still struggles with jealousy, Mr. Lambchop still is the epitome of practicality, Mrs. Lambchop is still the guardian of the family’s grammatical and physical health, and Stanley still sometimes wishes he wasn’t flat. Stanley’s parents are not portrayed as prominently in these books. Even when the family travels together, Stanley sometimes becomes separated from his parents and/or Arthur. In these stories, the parent’s presence is conveyed through Stanley’s remembering. For instance, in The US Capital Commotion, the 9th book in the series, Stanley says “Everyone must be worried sick (43),” and then smiles as he thinks of how his mother would correct his grammar, saying “You mean that everyone is sick with worry” (44). Thus far, the nine books in the Worldwide series have taken Stanley to two points within the United States (South Dakota’s Mount Rushmore and to Washington D.C.), as well as to Egypt, Japan, Canada, Mexico, Africa, China, and Australia. All but one of the books (The Flying Chinese Wonders, book 7) includes an appendix containing an assortment of facts, mostly historical and/or geographical, about the places Stanley has visited. Each cover features Stanley surrounded by cultural icons or symbols of the culture visited in the book--or, at least, what white, middle-class, suburban Americans perceive as symbols of particular cultures. The cover Anderson and Powell 17 of The Japanese Ninja Surprise, for instance, features a large, red, circle against an orange, clouded sky, intended to recall the Japanese “Rising Sun” flag. Superimposed over the sun is Stanley, wearing a ninja mask and uniform, hands stiff in a martial arts defensive pose and legs and feet positioned as though delivering a flying kick. Across the bottom, from left to right, are smaller iconic symbols: a bonsai-styled tree, a torii or Japanese gate usually seen at the entrance to a Shinto shrine, a conical mountain reminiscent of Mt. Fuji, and another bonsai-style tree. Each of the books introduces Stanley, and sometimes his family, to what are portrayed, as Laubscher and Powell termed it, as “exotic otherness” (221)--usually involving traditional foods, iconic ethnic or historical symbols, and well-known locations--which are “celebrated” by Stanley and/or his family. When Stanley travels to Canada, for instance, he eats caribou stew, and “a satisfying meal of dried fish and boiled walrus” (46); in Egypt, Stanley “marvels” at the treasures from ancient Egyptian tombs (18); in Mexico, Stanley accidentally becomes the matador’s cape in a bullring. Even people and locations within the United States are treated as exotic and as other. The first book in the series takes the suburban Lambchop family to the more rural South Dakota’s Mount Rushmore National Monument where they meet an all-but rootin’, tootin’ cowgirl named Calamity Jasper who speaks cowboy-ese (“”thar’s gold in them thar hills” [23]). She also teaches the boys to do rope tricks with a lasso, and needs to be saved from a gold-mine cave-in. Portraying people and locations as exotic and other is one thing; portraying them inaccurately is another. While Calamity Jasper is portrayed as a cowgirl and gold miner, she also identifies herself as being part Lakota Sioux. However, as Debbie Reese, former assistant professor at the University of Illinois and founding member of the university’s Native American House and American Indian Studies program, points out, Lakota Sioux people in South Dakota probably Anderson and Powell 18 would not be involved in gold mining, as the Black Hills area was and is considered sacred to the Sioux. Reese, a Nambe Pueblo Indian woman, finds other aspects of Calamity Jasper’s portrayal as problematic. Reese writes, “In addition to knowing "useful things" about plants and hunting (can you say STEREOTYPE?), she knows how to send smoke signals (come on, say it again: STEREOTYPE). Course, because Stanley is FLAT, they use him as the blanket to send those smoke signals” (Web). In addition to portraying the people and cultures visited as exotic and as other, the series portrays them—and the Lambchops as “us”—with a sense of absurdity. Recalling Stern’s description of absurdity as presenting a story “in which characters behave irrationally, where causal sequences of events are illogical, and where incongruous juxtapositions of people and things occur,” we turn now to a discussion of the absurdities in the Worldwide Adventure Series of Flat Stanley stories. Absurdity and the Worldwide Adventure Series Just as the Worldwide Adventure Series maintains the ethnocentric perspective of the Lambchop family, so it also continues to insert elements of the absurd into each story. Each book begins by recalling the premise of the original story: Stanley was flattened when a bulletin board fell on him, and he now is half-an-inch thick. Each book recalls his parents’ often misplaced concern for (culturally constructed) proper manners, grammatically-correct speech, and appropriate hygienic habits. But the cultures Stanley visits and the people he meets are also often exaggerated; and we suggest the exaggerations are taken beyond the point of stereotype and reach the point of absurdity. In The Amazing Mexican Secret, book five of the WWAS, for instance, Stanley’s and Arthur’s next-door neighbor, Carlos plays matador, using Stanley as the cape and featuring Anderson and Powell 19 Arthur as the bull. Carlos interjects Spanish words into the conversation, and says he has a cousin who is a famous matador in Mexico, so bullfighting is “in my blood” (7). For breakfast, the Lambchops eat huevos rancheros with tortillas seasoned with some special seasoning given to Mrs. Lambchop by Carlos’ mother, the recipe for which Carlos says came from his 103-yearold grandmother in Mexico. The recipe is sought after by “spies” (9), and the grandmother will not trust it to the mail system; so Mrs. Lambchop exhibits irrational behavior by deciding to mail Stanley to Mexico to retrieve the recipe before it dies with the grandmother. Not only does Mrs. Lambchop decide to send Stanley, she does so with such expediency that she doesn’t even suggest he change his clothes. Even Stanley comments that she “usually seemed more concerned about his health and safety” (12). In short order, Stanley arrives in Mexico where he is centerring at a real (albeit, bloodless) bullfight, is hung in a tree as a pinata at a fiesta, and is led by a group of children (!) on a three-day journey by foot to a Mayan temple where he cliff-dives into a pool of water, discovers an underground tunnel which leads to the home of Carlos’ grandmother. French-speaking, French-named chefs--another stereotype--follow him and try to get the secret seasoning, as well. There’s more, but this over-the-top series of irrational characters, illogical events, and “incongruous juxtaposition[ing] of people and things,” as Stern describes it, suggests the text may actually be making fun of the idea that so-called multicultural literature can be written in a way that both causes the reader to glimpse another culture and offends no one. As noted previously, Stern calls the use of absurdity a “literary tactic,” one of several which, she says, “disrupts conventional notions about meaning by questioning its very existence” (75). In particular, Stern writes, “Absurdist fiction rebels against the beliefs and values of traditional western culture....” (76). In our traditional Western culture, we have come to believe-- Anderson and Powell 20 rightly or wrongly--that we have an obligation to produce and promote children’s literature that reflects a world seen through a lens that is other than white, middle-class, suburban Americans. The problem is most children’s authors are white, middle-class, suburban Americans, and Derrida’s paradoxical conundrum says that, at the moment we realize we are viewing the world from an ethnocentric lens, it is ethnocentric thinking that enables us to realize our own ethnocentricity. But so is every depiction of every culture. Jeff Brown’s depiction of white, middle-class suburban Americans cannot possibly speak for all people who fall into that particular category, which means not all people in that category necessarily view the world through the exact same lens. Mildred Taylor’s Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry cannot speak for all Black people living in the 1930s, not even for all Black people living in rural Mississippi in the 1930s. All any one story can do is to present one perspective, to help the reader see through one other person’s lens, a lens that is different from that of the reader. Again, because the author of the text is not conveying information in a straightforward manner, but is instead presenting a story “in which characters behave irrationally, where causal sequences of events are illogical, and where incongruous juxtapositions of people and things occur” (76), the reader must, as Stephens put it, decode this macro-discourse in order to understand the intended meaning of the author and to be able to determine its significance in terms of literary theme and social implications. As Stern writes, “The burden of interpretation is on the interpreter....” (76). Absurdity takes things to ridiculous extremes and, in so doing, stretches our thinking until we see the joke for what it is. In the process it recalibrates the oncefamiliar into a more expanded version of reality. Anderson and Powell 21 Conclusion Brooks (1947) cites I.A. Richards’ thoughts about metaphor being the only way to express the “subtler states of emotion” (in Rice and Waugh, 2010, 56); and Flat Stanley can be seen metaphorically, as well, in the sense that, while Stanley is physically flat, the stories themselves reveal his own flat thinking, the flat thinking of those around him, and, by extension, the human tendency toward flat thinking, as well. For example, in WWAS number eight, The Australian Boomerang Bonanza, Arthur and Stanley meet Mr. Billabong, who is butler to another character. He is “an unshaven man wearing shorts, a t-shirt, and hiking boots” (20). Stanley says, “You don’t look like a butler.” Mr. Billabong grinned. “Yeah, well you don’t look like a person, but you are, aren’t ya?” (21). Stanley’s ethnocentric lens is revealed for what it is. It is no longer enough to celebrate the exotic otherness of other cultures; the reader is challenged to see beyond culture and see people as people. Discourse, as Stephens writes, consists of both language and narrative, the micro- and macro-discourses which, combined, must be decoded by the reader in order to derive meaning from and attach significance to a text. This examination of the macro discourses of ethnocentrism and absurdity, through the micro discourses of text and illustration, within the Flat Stanley series, suggest the notion of multicultural literature is in itself an absurdity. Academicians who challenge the complexity of this reasoning might consider Donald Macedo’s thoughts. Echoing Derrida, Donald Macedo wrote, in his introduction to Pedagogy of the Oppressed, “ I am often amazed to hear academics complain about the complexity of a particular discourse because of its alleged lack of clarity. It is as if they have assumed that there is a monodiscourse that is characterized by its clarity and is also equally available to all. If one begins to Anderson and Powell 22 probe the issue of clarity, we soon realize that it is class specific, thus favoring those of that class in the meaning- making process” (22). Recognizing the impossibility of writing through a culturally neutral and undistorted lens may be the first step toward an honest discussion of multicultural literature. Anderson and Powell 23 Works Cited Apter, Michael J., and Mitzi Desseles. “Disclosure Humor and Distortion Humor: A Reversal Theory Analysis.” International Journal of Humor Research 25.4 (2012): 417-435. De Gruyter Mouton. Web. 12 Mar. 2013. Arias-Bolzmann, Leopoldo, Goutam Chakraborty, and John C. Mowen. “Effects of Absurdity in Advertising: The Moderating Role of Product Category Attitude and the Mediating Role of Cognitive Responses. Journal of Advertising 29.1 (2000): 35-49. M.E. Sharpe, Inc. Web. 12 Mar. 2013. Boyd, Brian. On the origin of stories: Evolution, cognition, and fiction. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2009. Print. Campbell, Joseph. The hero with a thousand faces, 3rd ed. Novato, CA: New World Library, 1949/2008. Print. Derrida, Jacques. “Structure, Sign and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences,” Trans. in Alan Bass Writing and Difference (1966): 278-95. Rpt. in Modern Literary Theory: A Reader 4th ed. Ed. Philip Rice and Patricia Waugh. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2010. 195-210. Print. Friedman, Thomas L. The World is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-first Century. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2005. Print. Laubscher, Leswin, and Susan Powell. “Skinning the Drum: Teaching about Diversity as “Other”. Harvard Educational Review 73.2 (2003): 203-224. Harvard Education Publishing Group. Web. 13 Mar. 2013. Macedo, Donald. Introduction. Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 30th Anniversary Edition. By Paulo Freire. Trans. Myra Bergman Ramos. New York: The Continuum International Anderson and Powell 24 Publishing Group, Inc., 1970/2000. Print. Nodelman, Perry, and Mavis Reimer. The Pleasures of Children’s Literature, 3rd ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 2003. Print. Reese, Debbie. “Flat Stanley’s Worldwide Adventures: The Mount Rushmore Calamity.” American Indians in Children’s Literature, americanindiansinchildrensliterature.blogspot.com/2013/01/flat-stanleys-worldwideadventures.html, 25 Jan. 2013. Web. 14 Mar. 2013. Shklosky, Victor. Excerpt from “Art as Technique.” Trans. and Ed. in T. Lemon and M. J. Reis, Russian Formalist Criticism: Four Essays (1917), pp. 11-15, 18. Rpt. in Modern Literary Theory: A Reader 4th ed. Ed. Philip Rice and Patricia Waugh. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2010. 49-52. Print. Stephens, John. Language and Ideology in Children's Fiction. New York: Longman, 1992. Print. Stern, Barbara B. “‘Crafty Advertisers’: Literary Versus Literal Deceptiveness.” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 11.1 (1992): 72-81. American Marketing Association. Web. 12 Mar. 2013. Weil, Danny. "Towards A Critical Multicultural Literacy: Advancing An Education For Liberation." Roeper Review 15.4 (1993): 211. Academic Search Premier. Web. 14 Mar. 2013. Children’s Literature Referenced Books by Jeff Brown. Flat Stanley. Illus. Tomi Ungerer. New York: HarperCollins, 1964. www.browseinside.harpercollinschildrens.com/index.aspx?isbn13=9780060206819. Web. Anderson and Powell 25 Flat Stanley, 40th Anniversary Edition. Illus. Scott Nash. New York: HarperCollins, 2003. Print. Flat Stanley: His Original Adventure. Illus. Macky Pamintuan. New York: Harper, 2009. Print. Stanley and the Magic Lamp (1983) Stanley In Space (1985) Stanley's Christmas Adventure (1993) Invisible Stanley (1995) Stanley, Flat Again! (2003) Flat Stanley Worldwide Adventure Series. All illustrated by Macky Pamintuan. The Mount Rushmore Calamity (2009) - author Sara Pennypacker The Great Egyptian Grave Robbery (2009) - author Sara Pennypacker The Japanese Ninja Surprise (2009) - author Sara Pennypacker The Intrepid Canadian Expedition (2010) - author Sara Pennypacker The Amazing Mexican Secret (2010) - author Josh Greenhut The African Safari Discovery (2011) - author Josh Greenhut. The Flying Chinese Wonders (2011) - author Josh Greenhut The Australian Boomerang Bonanza (2010) - author Josh Greenhut The US Capitol Commotion (2011) - author Josh Greenhut Anderson and Powell 26 Appendix A. Title Cover Illustration Setting / Plot Depiction of main character in culture Setting: Stanley’s home, city park, and Famous Museum of Art downtown Note: Adults are drawn with four fingers & thumb; Arthur & Stanley are drawn with three fingers & thumb Arthur: Black hair, usually tousled; dark eyes; pointy chin; often wears tshirt, jeans, sneakers Mr. Lambchop: tall, broadshouldered; strong jaw; dark hair; wears sweater w/ collared shirt under, sometimes a tie; works in an office (17) Mrs. Lambchop: shorter, slim, exercises (Ninja, 72), light hair Doctor Dan: Older man, balding, bushy white eyebrows and bushy white mustache Female nurse: youngish; wears Stanley’s response Fantastic Facts- Flat Stanley (Original) / 1964 Author: Jeff Brown Illustrator: Scott Nash Flat Stanley: His Original Adventure (Redrawn) / 1964/1992 text c. Jeff Brown / 2009 illustrations c. Macky Pamintuan Author: Jeff Brown Illustrator: Macky Pamintuan Stanley from waist up, emerging from mailer envelope; wearing green tshirt shirt trimmed in blue with white long sleeves; neat brown hair, dark blue eyes; light skin; squared forehead & pointy chin; envelope is on brownish rug on wooden floor; white baseboard, blue walls; legged piece of furniture behind Plot: Bulletin board falls on Stanley during night and flattens him; takes trip to California by being mailed in envelope (no scene set in California); is flown as a kite by Arthur; foils museum robbery and catches two thieves; is reinflated by Arthur, who uses a bicycle pump None Anderson and Powell 27 Title Cover Illustration Setting / Plot Depiction of main character in culture Stanley’s response Fantastic Facts- Stanley agreed to be rolled up like blanket on back of “Gold Rush”, Calamity’s horse. “I am very limber” (27). Caused a collapse in gold mine. Used self as lever to free Calamity Jasper. “What You Need to Know to be a Black Hills Gold Miner” cap; measures Stanley Ralph Jones: Mr. Lambchop’s friend from college; blond hair; wears sweater and collared shirt Mr. Dart: Museum director; tall, dark hair, pencil mustache, wears suit and tie; wants Stanley to dress as a girl shepherdess Thieves: Luther is fat and “dopey”; Max is thin w/hook nose and dastardly grin Police: No police pictured FS’s Worldwide Adventure s #1 The Mount Rushmore Calamity Author: Sara Pennypack er Illustrator: Macky Pamintuan Cover Art: Macky Pamintuan Cover Design: Jennifer Heuer Mount Rushmore; Stanley (smiling) flying over monument while attached to “lasso” Arthur tossed to him. 1-Mount Rushmore State Park, S. Dakota 2-Idea of Amc. west Plot: Family vacationing at Mt. Rushmore; Arthur falls and Stanley positions himself as bridge to save him; becomes hero for saving face on Mt. Rushmore; boys meet Calamity Jasper; collapse in gold mine; Stanley resues her; they are lost; Stanley used to send smoke signals; reunited Calamity Jasper: tour guides daughter; speaks in “cowboy-ese”; wears a leather vest, chaps, and dusty boots w/silver spurs (20,21) part Lakota Sioux (48);; female “heroine” ; only female character other than Mrs.Lambchop Ranger Bob: called Stanley, “Flat boy” (17).Mr. and Mrs. Lambchop were “indignant” because he “has a name”(17). He was used to send smoke signals. “Stanley very bravely held his breath and didn’t cough once” (51). Native Americans lived in Black Hills for more than 9,000 years. Gold Rush began in 1874; gold first discovered few miles from where Mt. Rushmore built. Calamity Janeone of most famous cowgirls. Friends w/Wild Anderson and Powell 28 Title Cover Illustration Setting / Plot Depiction of main character in culture Stanley’s response w/family. Fantastic FactsBill Hillcock. Info on fools gold. FS’s Worldwide Adventure s #2: The Great Egyptian Grave Robbers Nine chapters / 81 pages (plus facts pages) Author: Sara Pennypack er Illustrator: Macky Pamintuan Cover Art: Macky Pamintuan Cover Design: Jennifer Heuer Typical Egyptian tomb art; Stanley positioned between two standing hieroglyphic figures, arms bent at the elbow—one up, one down—and knees positioned as if running. His eyes look to the left as he runs or points to the right. Setting: Unnamed city in Egypt, but with National Historical Museum (ironic because there isn’t one: http://www.egypt independent.com/ news/wantednatural-historymuseum-egypt); bazaars; near Nile River; eats falafel, kebobs, dates (no explanation); bazaar vendors mixed—one bare-headed, one with a fez; ride camel to tombs Stanley has himself wrapped as a mummy to surprise Arthur Plot: Stanley mailed to Egypt; Catches (native) tomb robbers Amisi: daughter of curator of National History Museum; wears t-shirt, short pants, sandals/sneakers; “very pretty” (69); only female character other than Mrs. Lambchop Amisi’s father: Says, “Holy sarcophagus!” Wears turban, suit-&-tie, trimmed beard & mustache Uniformed Guard: Wears fez, dark pants & short jacket, light top, sandals; mustache, long face, ominous eyes Sir Abu Shenti Hawara IV: sits cross-legged on “goldembroidered cushion” in tent w/oil lamps & incense; wears jeweled turban, robe, jacket, top, pants, barefoot (or sandals with toes than curl up to point); longer beard & mustache; smokes pipe; claps hands to summon guards; “Stanley found it [food] all very tasty” (15). “Stanley admired the black images on the wall” (17); he learns they are hieroglyphs, the ancient Egyptian writing system. “Stanley saw many amazing things” [ancient Egyptian treasures in the museum] and “marveled” at them (18). “Stanley knew it was important to be polite, even when faced with rudeness” (29), referring to Sir Hawara’s measuring him. Thinks Sir Hawara’s handclapping is rude (56). Thinks Mom would say, “Hay is for camels” instead of “Hay is for horses” as she “was also always one to appreciate her surroundings (71). “What You Need to Know to be an Egyptologist” Location of Egypt and Cairo. Nile may be longest river in world. Great Pyramid of Giza only one of Seven Wonders of the Ancient World still standing & structural info. Info on ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic writing. Info on ancient Egyptian process of mmufication. Sahara desert largest sandy desert on earth. Anderson and Powell 29 Title Cover Illustration Setting / Plot Depiction of main character in culture Stanley’s response Fantastic Facts- tomb-robber Police officers: Wear berets, uniforms w/jacket, diagonal belt, baggy pants tucked into boots. No beard/ mustache FS’s Worldwide Adventure s #3: The Japanese Ninja Surprise Nine chapters / 96 pages (plus facts pages) Author: Sara Pennypack er Illustrator: Macky Pamintuan Cover Art: Macky Pamintuan Cover Design: Alison Klapthor The center of the cover features the Japanese rising sun against orange, clouded sky, with Stanley, wearing a ninja mask and garments, superimposed over it. Across the bottom, from left to right, is a bonsai-styled tree, a torii or Japanese gate (Shinto shrine), conical mountain reminiscent of Mt. Fuji, and another bonsaistyle tree. Setting: Tokyo, Japan (32); Oda Nobu’s home made of “delicate rice paper stretched across wooden frames,” no furniture except a mat on a low platform (bed); wears a kimono; tearoom in home and tea ceremony; garden w/bonsai trees; history of ninjas and ninjutsu (‘the art of stealth’ p. 27); wears a black silk ninja uniform (30); visits restaurant and eats sushi, then karaoke bar— chef bows /people applaud “wildly”; travels via Shinkansen (bullet train) to southwest Japan near East China Sea to see cherry blossoms and volcanic hot springs; pagoda on an island; Imperial Palace, zoo, sumo match, Master Oda Nobu: Movie star of Japanese martial arts films; long face, flat nose, thick lips, eyes more round than slanted; performs tea ceremony; his garden has bonsai trees; turns out not to be warrior, but becomes a student;; tosses Stanley into air like kite (he falls), then uses him as sun shield, then turns him into origami star at a reception (wears Westernstyle jacket and tie); apologizes to Stanley for “disrespectful behavior” (4142); call each other Oda-san and Stanley-san ( Ninja Guards: black uniforms w/full face-hoods tied behind head; only eyes show ”wide-eyed” so rounded; do not look Asian at all; non-descript; turn Stanley & Arthur play ninja warriors & say, “Hiii-yaah!” (2) “Stanley could tell that the careful motions [of the tea ceremony] had taken a lot of practice to learn” (23) The tea tasted”interesting ” (24) “The food was delicious, even the seaweed and the smoked eel” (and, presumably, the raw fish) (32-3); At karaoke bar, Stanley sings and “drank three sodas that tasted exactly like bubble gum. He loved Japan!” (33). Arthur “”beaming with happiness” at being surrounded by four girls “who were folding little origami animals and giving them “What You Need to Know to be a Japanese Ninja” Geographical features of Japan’s islands History of first ninjas (700 years ago) Considered polite to slurp noodles in Japan Geological features of Japan and earthquakes Etiquette of bowing in Japan Art of origami and legend of the thousand origami cranes Anderson and Powell 30 Title Cover Illustration Setting / Plot Plot: Arthur mails Stanley to Japan so they can get Master Oda Nobu’s autograph; he ends up being Nobu’s personal ninja; Nobu is kidnapped by real ninjas and Stanley saves the day FS’s Worldwide Adventure s #4: The Intrepid Canadian Expedition Eight chapters / 87 pages (plus facts pages) Author: Sara Pennypack er Illustrator: Macky Pamintuan Cover Art: Macky Pamintuan Flat Stanly is a snowboard soaring above powdery drift, with snowy mountain topped with a few fir trees and blue sky in the background; Stanley wears a red sweatshirt with Canada’s MapleLeaf on the front, blue pants, no hat, scarf, jacket, mittens, or goggles. Another boy, wearing those items, “rides” Stanley. Setting & Plot: Begins in British Columbia (identified only on back cover) where Lambchop family is skiing; Stanley & a friend carried by wind to Northwest Territories and visit Inuit people; see Northern lights (aurora borealis); ride dog sled to Calgary w/ cowboy; ride to Quebec with Mountie in cruiser; stop in Ottowa for hockey game; fly in plane to Niagra Falls; Depiction of main character in culture Stanley’s response out to be just bodyguards, not ninjas Tailor: Wears Western-style suit and tie; glasses; only character to not have rounded eyes (31) Real Ninjas: Scream “Aiiieee!” when they kidnap Oda Nobu; turn out to be four girls “craziest fans ever” (80) and “very disrespectful girls” -eyes closed or rounded; only female characters other than Mrs. Lambchop to him” (81). Nick: Doctor Dave’s son (Doctor Dave was Doctor Dan’s roommate in medical school); tried to outdo Stanley in every- thing Tulugaq: Inuit man (not Eskimo) who wears fur trimmed parka and has sled dog, but lives in wooden house (“There is a lot you don’t know about my culture.” 38) with roaring fire and eats caribou stew; use phone to call parents (fire for Fantastic Facts- “What You Need to Know to be a Royal Canadian Mountie” Native origin of word ‘Canada’ Official languages Canada/U.S. border info Niagra Falls & barrel riders Canada’s coastline longest in world & on three oceans Ice hockey & Stanley Cup Anderson and Powell 31 Title Cover Illustration Cover Design: Alison Klapthor FS’s Worldwide Adventure s #5: The Amazing Mexican Secret Eight Chapters / 89 pages (plus facts pages) Author: Josh Greenhut Illustrator: Macky Pamintuan Cover Art: Stanley, holding a sombrero, stands in a market set during a fiesta (pinata, colorful banner, confetti); market features oranges, water- melon, corn, yellow bell peppers, white and red roses, and what might be limes, tamarinds, cactus paddles, etc. Stanley wears a green t-shirt trimmed with red and with white long sleeves Setting / Plot Depiction of main character in culture Stanley becomes barrel and they go over the falls, attend a wedding (all cliches!) heat but a phone?) Shaman: Lives in Tulugaq’s village & is “wise”; “small, ancient hut” with “walls lined with animals furs and weavings and ancient artifacts” (42); wears a “monstrous mask” has Tulugaq play a skin drum while he chants and dances “almost as if he was in a trance” (44); “smiled broadly, without a tooth in his head” (44); prophesied over boys and took from his pouch worn around his neck a postcard of Niagra Falls Setting: Stanley travels by mail to Mexico City, where he visits the Plaza de Toros México; travels to a Mayan temple, and Stanley’s response Fantastic Facts- More Stanley Cup Wood Buffalo National Park “More Amazing Mexican Secrets!” Mexico 3rd largest country in Latin Am & has most Spanish speakers in world Each color in flag “deeply” symbolic Mexico’s volcanoes & Pacific “Ring of Fire” 60+ Indigenous languages Anderson and Powell 32 Title Macky Pamintuan Cover Design: Alison Klapthor Cover Illustration Setting / Plot Depiction of main character in culture Stanley’s response (colors of Mexican flag) and dark blue pants. Shoes/ feet not visible. Fantastic Facts- “Day of the Dead” Chocolate U.S./Mexican border length Mexico City 2nd largest in world FS’s Worldwide Adventure s #6: The African Safari Discovery Author: Josh Greenhut Illustrator: Macky Pamintuan Cover Art: Macky Pamintuan Cover Design: Alison Klapthor Stanely, with a concerned look on his face, soaring over safari animals giraffe, elephant, gazelles- Nairobi, Kenya; Africa Family sees Mt. Kilimanjaro & Lake Victoria from airplane; on a safari; on the river; at archaelogical site Plot:Stanley, Arthur and Mr. Lambchop travel to Africa to see the “flat skull” discovery; Mr. Lambchop & Arthur parachute out of plane; Stanley jumps w/out chute. Find “flat skull”; Arthur identifies it as a fish, not a human skull. Odinga: African boy at airport wearing t-shirt w/picture of Stanley in Japan; doesn’t speak English. Introduces Lambchops to his sister. Bisa: African girl who speaks broken English; takes Lambchops to meet her dad, a pilot for the police. Captain Tony: Bisa’s father; pilot for police force; Masai tribes man: “tall man w/enormous holes in his earlobes” (55). Body draped in red cloth; staff taller than Stanley; spoke English & French; graduate of the Sorbonne in Paris Masai woman: clothed in red; After learning of discovery of flat skull from Mr. Dart (director of Famous Museum & neighbor), Stanley declares “I want to get mailed to Africa” (9). Stanley wants to see if the skull is “the same as me” (10). Bisa asked why they wanted to go to Tanzania. Stanley said “I’m looking for answerrs” (22). When face to face w/a lion, Stanley camouflaged himself to show only his side so he’d look like another blade of grass. He told his dad, “I’m okay. A lion almost ate me, but I tricked him” (45). When Masai tribesman came close to look at “What You Need to Know to Go On Your Own African Safari” 4 of 5 fast land animals in Africa: cheetahs, wildebeest, lions & Thomson’s gazelle Africa-2nd largest continent; 11,699,000 sq. miles; about 22% of earth’s land area. Over 50 countriesmore than any other continent Giraffes Zebras never domesticated like horses. Elephants-6/7 tons; no natural enemies; not predators Namib desert Anderson and Powell 33 Title FS’s Worldwide Adventure s #7: The Flying Chinese Wonders Author: Josh Greenhut Illustrator: Macky Pamintuan Cover Art: Macky Pamintuan Cover Cover Illustration Stanley, with a smile, in a backflip over the Great Wall of China Setting / Plot Setting: school auditorium; Beijing, China; the Great Wall of China Plot: Stanley accidentally drops a heavy light on Yang’s foot and broke it. He tries to make up for it by traveling to China to help out in the New Years’s show. Depiction of main character in culture Stanley’s response Fantastic Facts- “held baby wrapped in patterned cloth close to her body” (56). Dr. Livingston Fallows: wore high boots, khaki pants, brown shirt; had British accent; identified himself as “world’s greatest ologist” (72). “Anthropologist , paleontologist, archaeologist, et cetera” (73). Stanley, he “flinched as the man leaned close and peered behind Stanley’s head” (57). Stanley used as paddle when they drop theirs in the river. When they found out skull was w/Dr. Fallows, Stanley’s “voice was shaking” “May I see the skull?” (74).Stanley ran from scene when they discovered it wasn’t a human skull. Cried and said “”We came all this way, and...I didn’t find out anything about ….about why I’m flat” (79). Africa-almost an island-only connection to other land is Sinai Peninsula in Egypt Yin: Chinese girl Yang: Chinese girl’s twin brother; together they are the Flying Chinese Wonders Great Uncle Yang: a squinting old man, w/3 long white hairssprouting from his chin; a contortionist Stanley tries Chinese food; rice with meat cooked in a leaf; spicy pork and vegetables; turnip cake; biang, biang noodles-”which were almost as flat and wide as he was” (29) none-there was a recap of his adventures thus far Anderson and Powell 34 Title Cover Illustration Setting / Plot Depiction of main character in culture Stanley’s response Fantastic Facts- Stanley, in the shape of a boomerang, over the desert. Arms are folded over his chest; kangaroo looking at him. Setting: family living room; Great Barrier Reef; outback/buh; UluruAboriginal name for Ayers Rock Mr. Wallaby: a barrel chested man w/a leather wide brimmed hat; cereal magnate When Stanley saw Bongo, he said “You don’t look like a butler” (20) to which Mr. Billabong replied, “You don’t look like a person, but you are, aren’t ya?” (21). What you need to know before your own adventure down under Design: Alison Klapthor FS’s Worldwide Adventure s #8: The Australian Boomeran g Bonanza Author: Josh Greenhut Illustrator: Macky Pamintuan Cover Art: Macky Pamintuan Cover Design: Alison Klapthor Plot: Stanley and Arthur win a trip to Australia. They fly, without their parents. The first adventure is surfing, with Stanley as the board. The boys snorkeled on the Great Barrier Reef.Arthur send Stanley into the air, in the shape of a boomerang, and Stanley is carried by the wind into a storm. Stanley landed in the Australian outback where he learned he could hop like a kangaroo. He met a bush tracker, who captured a wild horse and began to take him to the reef. On the way, they met the others in a jeep, looking for Bongo: Mr. Wallaby’s butler; an unshaven man wearing shorts, a t-shirt, and hiking boots. Sheila: Mr. Wallaby’s chef Assistant asks “Should I throw some more prawns on the barbie?” (30) Arthur says to Stanley, “Maybe this is that rhyming slang Mom told us about”. (30) Stanley The name Australia comes from Latin Terra Australis Incognitomeans Unknown Southern Land. Average of 3 people per sq. kilometer. One of lowest population densities in world. Sheep outnumber people by almost 8 to 1; 150 million sheep; only 20 million people. Only continent occupied by only 1 nation. Lowest & flattest continent. Great Barrier Reef more than 2,000 km long; it’s only living thing astronauts in International Space Station can see from space w/out a Anderson and Powell 35 Title Cover Illustration Setting / Plot Depiction of main character in culture Stanley’s response them. FS’s Worldwide Adventures #9: The US Capital Commotion Author: Josh Greenhut Illustrator: Macky Pamintuan Cover Art: Macky Pamintuan Cover Design: Alison Klapthor Capital in the background; Stanley’s shirt has stars on it; pants are stripes. Looks like a flag; mouth open smile. fireworks in the air Setting: Washington, D.C. Plot: Stanley and his family travel to Washington DC so he can receive a Medal of Honor. When they arrive, Stanley is separated from his family and being tracked by two unknown men. Fantastic Factstelescope. female president secret service men Stanley remembers what Japanese movie star said, “Your flatness is what makes you special” (45). It is what you are but not who you are What you need to know before your own adventure in the capital! President says she decided to award him the medal. He asks why. She says, “Because you use what’s different about you to make people all over the world realize what we have in common”... :”You’ve traveled the globe, showing people that when they have the freedom to be different, they can achieve amazing things” (57) Official flag of D.C. has 3 red stars & 2 red strips on white backgroundbased on shield from George Washington’s family coat of arms. Washington, DC named after C. Columbus DC residents pay taxes, but don’t have representative in Congress. Have license plates that say “No taxation w/out representation” National Air & Space Museum in D.C.-most popular museum in world-more than million visit every year. Lincoln was 6’4”; status of him inside Lincoln Memorial nearly 19 feet. Official motto of DC is Justitia Omnibus; Latin Anderson and Powell 36 Title Cover Illustration Setting / Plot Depiction of main character in culture Stanley’s response Fantastic Factsfor “justice to all” White Houseoriginally called “Executive Mansion” or “President’s Palace”. Reporter called it white house in newspaper article & Theodore Roosevelt made it official name in 1901. T. Roosevelt kept animals in White House for his family. National Press Club, in DC, is only building in US to have its own zip code.