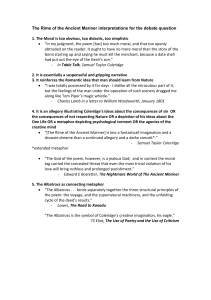

attachment 1

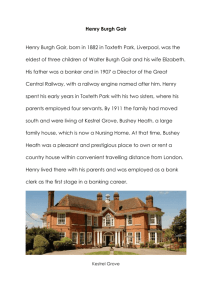

advertisement