Undetermined Natural Causes - Institutional Repositories

advertisement

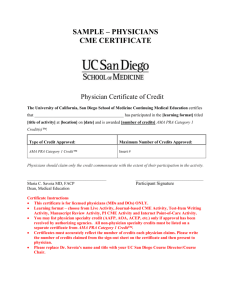

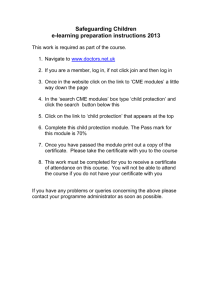

Copyright by David B. Trant, M.D. 2010 The Capstone Committee for David B. Trant, MD Certifies that this is the approved version of the following capstone: Undetermined Natural Causes: Do Physicians Code for Uncertainty In Cause of Death? Committee: Susan C. Weller, PhD, Supervisor Christine M. Arcari, PhD, MPH Karl Eshbach, PhD __________________ Dean, Graduate School Undetermined Natural Causes: Do Physicians Code for Uncertainty In Cause of Death? by David B. Trant, M.D. Capstone Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas Medical Branch in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Public Health The University of Texas Medical Branch August, 2010 Undetermined Natural Causes: Do Physicians Code for Uncertainty In Cause of Death? Publication No._____________ David B. Trant, MD, MPH The University of Texas Medical Branch, 2010 Supervisor: Susan C. Weller Abstract Cause of death (COD) determination by physicians on the death certificate can be difficult when the conditions leading to death are unclear or uncertain. The Center for Disease Control (CDC) recommends the classification for these deaths should be “undetermined natural causes” (ICD-10 code R99). Physicians may incorrectly code COD in patients who die of undetermined natural causes, instead listing heart disease (ICD-10 I00-I09, I11, I13, I20-I51)), or another COD, on the death certificate. This may have important implications in the calculation of mortality statistics, particularly when using the Mortality Medical Data System (MMDS), a system to automate the entry, classification, and retrieval of cause-of-death information reported on death certificates. Forty-two primary care physicians participated in a randomized, controlled trial assessing completion of the death certificate for a patient dying of undetermined natural causes. The physicians were randomized into two groups: the first group reported the COD using an open-ended format, and the second group selected COD from a list of potential choices (including “undetermined natural causes”) for the death certificate COD fields. The study has two aims. The first aim is to determine the percentage of physicians that correctly code the death certificate, and to see if responses are sensitive to having “nonspecific” COD as a possible response. The second aim is to assess the reliability of coding COD by comparing physician reported COD to the MMDS transformations of those reports. v Overall, 62.5% of respondents chose an underlying COD that was categorized as “symptoms, signs and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings, not elsewhere classified,” (ICD-10 codes R00-R99), and the remaining 37.5% reported a specific COD, such as heart disease (I00-I09, I11, I13, I20-I51). There was no statistical difference [χ2 (1, N = 40) = 1.932, p = 0.165] in the frequency of nonspecific R codes used by the respondents for the underlying COD completing either the open-ended format (52% nonspecific, 48% specific) compared to the close-ended format (74% nonspecific, 26% specific). Processing with the Mortality Medical Data System (MMDS) resulted in an underlying COD category of 27.5% non-specific R codes and 72.5% specific causes (60% were the heart disease category), nearly opposite the numbers for the original physician-reported underlying COD. The MMDS-generated COD did not show a statistically significant difference [χ2 (1, N = 40) = 2.489, p = 0.115] for frequency of R code generation between the open-ended format (38% nonspecific, 62% specific) and the close-ended format (16% nonspecific, 84% specific) . This study suggests that while the majority of physicians may correctly code for an underlying COD using codes R00-R99 for a person dying of undetermined natural causes, software used for national statistical reporting may be biased to report the underlying COD category as heart disease (I00-I09, I11, I13, I20-I51). vi Table of Contents List of Tables ....................................................................................................... viii List of Figures ........................................................................................................ ix BACKGROUND .....................................................................................................1 METHODS ..............................................................................................................8 RESULTS ..............................................................................................................14 DISCUSSION ........................................................................................................19 BIBLIOGRAPHY ..................................................................................................23 APPENDIX ............................................................................................................25 vii List of Tables Table 1. Table of possible sequences for the death certificate for the sample case with corresponding ICD-10 codes. ........................................................................................... 11 Table 2. Survey responders’ characteristics and use of R code for underlying COD ..... 14 Table 3. Physician-determined and software-generated underlying cause of death categories for each survey group based on the WHO ICD-10 classification. .................. 16 Table 4. Physician-Determined Underlying COD. X 2 (1, N = 40) = 1.932, p = 0.165 ... 17 Table 5. Software-generated underlying COD. X 2 (1, N = 40) = 2.489, p = 0.115......... 17 Table 6. Software-generated underlying COD specificity versus that determined by the physician. .......................................................................................................................... 18 Table 7. Comparison of heart disease diagnosis as the underlying COD category. ........ 18 viii List of Figures Fig. 1. U.S. Standard Certificate of Death (rev. 11/2003) ................................................. 2 Fig. 2. Case History No. 12 from Physician Handbook on Medical Certification of Death (Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, 2003). ................................................ 9 Fig. 3. U.S. Standard Certificate of Death (rev. 11/2003) excerpt. ................................. 10 Fig. 4. Single cause of death without other significant conditions. ................................. 20 Fig. 5. Cause of death with significant contributing condition in Part II......................... 21 ix BACKGROUND Physicians are often presented with the difficult task of determining cause of death (COD) when completing a death certificate which is then used to calculate national mortality statistics. Mortality statistics can be used to systematically assess and monitor the health status of populations and are useful in formulating policies to prevent or reduce mortality and improve quality of life. Unfortunately, physician errors in determining and coding COD and possible bias for listing specific causes over nonspecific or uncertain conditions may lead to inaccuracy of mortality statistics. This study explores physician coding of COD when faced with a case in which the patient dies of uncertain or nonspecific causes. The U. S. Standard Certificate of Death (Fig. 1) provides spaces for the certifying physician, coroner, or medical examiner to record pertinent information concerning the diseases or conditions that either resulted in (Part I) or contributed to (Part II) death. The medical certification portion of the death certificate expresses “the opinion of the certifier as to the relationship and relative significance of the causes which he reports.” (National Center for Health Statistics, 2010) A cause of death is the morbid condition or disease leading directly or indirectly to death. The underlying cause of death is the disease or injury which initiated the events leading directly or indirectly to death, and this physician-determined underlying cause of death is 1 Part I Part II Fig. 1. U.S. Standard Certificate of Death (rev. 11/2003) 2 the last condition listed in Part I of the death certificate. Other significant condition(s) which contributed to death but were not related to the immediate cause of death is (are) entered in Part II of the death certificate. (National Center for Health Statistics, 2010). Computer automation has greatly simplified the collection of mortality data and coding of the death certificate data using the ICD coding rules. Data collected from death certificates by government agencies is processed by the Mortality Medical Data System (MMDS) software. (CDC/ National Center for Health Statistics, 2010) This software is composed of four basic programs, SuperMICAR, MICAR200, ACME, and TRANSAX. These programs automate the entry, classification, and retrieval of cause-of-death information reported on death certificates and the software is used by state and federal agencies for statistical reporting of mortality data. SuperMICAR is designed to automatically encode cause-of-death data into numeric entity reference numbers. The output from this program serves as input for the MICAR200, which automates the multiple cause coding rules and assigns diagnosis codes described in the ICD to each numeric entity reference number. The ACME portion of this software applies the World Health Organization (WHO) rules to the ICD codes generated by MICAR200 and selects an underlying cause of death. The final program, TRANSAX, converts the ACME output data into fixed format and translates the data into a more desirable statistical form using the linkage provisions of the ICD, and is used for preparing files for transmission to the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) to provide statistical information that will guide actions and policies to improve the health of the US population. 3 Beginning in January 1999, the United States began using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) to classify causes of death reported on death certificates. ICD-10 is “designed to promote international comparability in the collection, processing, classification, and presentation of mortality statistics, including providing a format for reporting causes of death on the death certificate.” (CDC/ National Center for Health Statistics, 2009a) The reported conditions are translated into medical codes through the use of coding rules contained in the ICD. These rules allow for systematic selection of a single cause of death from the reported sequence of conditions on the death certificate. Using the ICD-10 rules, the underlying cause of death may actually be different than that determined by the physician on the death certificate. For example, Rule A specifies that when an ill-defined cause of death such as senility is listed on the death certificate along with a more specific diagnosis or diagnoses, the cause of death should be re-coded as if the ill-defined condition had not been reported. If the physician were to code the death certificate as “acute myocardial infarction” (coded as Acute Ischemic Heart Disease, Unspecified - I24.9) due to “advanced age” (coded as Senility - R54), then the physiciandetermined underlying cause of death per the death certificate instructions would be the last item listed in Part I; in this instance, Senility – R54. However, by application of ICD-10 Rule A, the underlying COD becomes Acute Ischemic Heart Disease, Unspecified - I24.9. 4 ICD-10 describes multiple diagnoses grouped into various categories roughly based on organ systems. This system works well when the cause of death is clear, and specific diagnoses can be found among these many categories. However, not all deaths have obvious specific causes; in such instances ICD-10 codes R00-R99 (Symptoms, signs and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings, not elsewhere classified) might be used to code a number of unclear, nonspecific or uncertain causes of mortality, such as R54 (senility), R98 (unattended death), and R99 (other ill-defined and unspecified causes of mortality). The plethora of possible diagnoses and their various combinations on the death certificate allow for great latitude by the physician in coding the cause of death. The innumerable potential combinations may lead to different coding of the cause of death for the same case by two different physicians. (Brown, et al., 2007) This variation in coding can have a negative impact when the ICD-10 coding rules are applied, potentially resulting in two very different reported diagnoses for the underlying cause of death. Some researchers have shown COD error rates ranging from 16% to 50%, which questions the validity of information from the cause-of-death registry for scientific or administrative purposes. Lakireddy et. al. (Lakkireddy, Gowda, Murray, Basarakodu, & & Vacek, 2004) showed that 45% of medical residents incorrectly identified a cardiovascular event as the primary cause of death using a sample case of in-hospital death due to urosepsis. Tavora et. al. (Tavora, Crowder, Kutys, & Burke, 2008) found 5 that in a series of autopsies on sudden deaths outside the hospital that the diagnosis of coronary artery disease on the initial death certificate rendered before autopsy was accurate only 50% of the time. James and Bull (James & Bull, 1996) described available malignancy histological diagnoses being recorded on only 23.6% of death certificates, as well as numerous other errors. In a literature review by Maudsley and Williams, (Maudsley & Williams, 1996) they noted that deriving a useful estimate of death certificate inaccuracies over multiple studies is difficult due to many inter-study differences in definition of error (i.e. undefined ‘major clinical cause’ when compared with autopsy, poorly defined clinicopathological correlation, variation in diagnostic coding) as well as the measurement of the error (autopsy, chart review). These death certificate errors may occur due to differences in medical opinion, training, knowledge of medicine, available medical history, symptoms, diagnostic tests, and available autopsy results. Even if extensive information is available to the certifier, causes of death may still be difficult to determine. Physicians may not be aware that it is acceptable to list a nonspecific or uncertain cause of death on the death certificate, although the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics (CDC/NCHS) has specifically addressed this problem: If the certifier cannot determine a descriptive sequence of causes of death despite carefully considering all information available and circumstances of death did not warrant investigation by the medical examiner or 6 coroner, death may be reported as “unspecified natural causes." (CDC/National Center for Health Statistics, 1997) Interestingly, the NCHS seems to suggest that choosing an unspecified COD suggests poor quality on the part of the physician certifier: One index of the quality of reporting causes of death is the proportion of death certificates coded to Chapter XVIII—Symptoms, signs and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings, not elsewhere classified (ICD–10 codes R00–R99). Although deaths occur for which underlying causes are impossible to determine, the proportion coded to R00–R99 indicates the consideration given to the cause-of-death statement by the medical certifier (CDC/National Center for Health Statistics, 2009). So on the one hand, the physician is encouraged to code for uncertainty where appropriate by the CDC/NCHS, but it is also suggested that such coding may not reflect adequate consideration by the physician. This obviously gives a mixed message to physicians considering using an unspecified COD, potentially biasing the physician to produce a more specific and potentially incorrect COD. Because physician reporting may be biased toward listing a specific disease or diseases rather than nonspecific or unknown causes when uncertain about the actual cause of death, this study tested for reporting differences between reports made when 7 “undetermined natural causes” is specifically a choice for cause of death and when it is not. This study also explores the differences between what a physician reports as the underlying COD on the death certificate, and what is reported for national vital statistics after coding the physician’s responses with the MMDS software. The study has two aims. The first aim is to determine the percentage of physicians that correctly code the death certificate, and to see if responses are sensitive to having “non-specific” COD as a possible response. The second aim is to assess the reliability of coding COD by comparing physician reported COD to the MMDS transformations of those reports. METHODS A randomized controlled trial was used to compare responses of physicians in two groups: one group reported the cause of death for a standardized case published by the CDC (Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, 2003) in an open-ended format, and the other group was asked to code the cause of death for the same standardized case by selecting from a list of ten potential sequences for Parts I and II of the death certificate COD. The protocol for this study was reviewed and declared exempt by the University of Texas Medical Branch Institutional Review Board prior to beginning data collection. SUBJECTS The subjects were physicians who identified their primary specialty as Family Practice or Internal Medicine and had primary practice locations in Baytown, Texas and the 8 surrounding communities of Highlands and La Porte, Texas. These subjects were identified from reviews of local phone books, internet listings, county medical society member rosters, information from local persons, and personal knowledge of the primary investigator. MEASURES Subjects were randomized into two groups to receive one of the two survey versions. Both versions contained a death case history (Fig. 2) from an example case: Case History A 92-year-old male was found dead in bed. He had no significant medical history. Autopsy disclosed minimal coronary disease and generalized atrophic changes commonly associated with aging. No specific cause of death was identified. Toxicology was negative. Fig. 2. Case History No. 12 from Physician Handbook on Medical Certification of Death (Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, 2003). No. 12 from the CDC’s Physician Handbook on Medical Certification of Death (Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, 2003). Version A included an excerpt from the U.S. Standard Certificate of Death (rev. 11/2003) in which the physician was asked to complete the cause of death section, item 32, Part I and II on this form for this example case (see Fig. 3). Version B had a list of potential sequences of causes of death that might be used on a death certificate for the example case, including the single listing of “undetermined natural causes” (see Table 1). The physicians who received this version were asked to choose the most appropriate 9 sequence applicable for this case. According to the CDC handbook, “undetermined natural causes” listed alone in Part I is the correct coding of cause of death for this case. Both versions of the survey (A and B) asked questions regarding specialty (Family Practice, Internal Medicine, other), years since medical school completion, prior formal training in death certificate completion (yes/no), how comfortable the physician was with completing a death certificate (scale), and whether the physician had completed training in their current primary specialty (yes/no). Additionally, the subjects were given a list of conditions/diagnoses leading to death (including the nonspecific conditions of Fig. 3. U.S. Standard Certificate of Death 11/2003) age) excerpt. undetermined natural causes and(rev. advanced and asked: “For the following diseases or conditions, please answer yes or no as to whether (in your opinion) this condition would ever be acceptable as a single cause of death on the death certificate, without listing any additional causes or conditions.” 10 Item 32, Part I Scenario # a. b. 1 Acute cerebrovascular accident (I64) 2 Cardiac arrhythmia (I49.9) Atherosclerotic coronary artery disease (I25.1) 3 Cardiac arrest (I46.9) Undetermined natural causes (R99) 4 Undetermined natural causes (R99) 5 Respiratory arrest (R09.2) 6 Undetermined natural causes (R99) 7 Acute myocardial infarction (I21.9) Atherosclerotic coronary artery disease (25.1) 8 Ruptured cerebral aneurysm (I60.90) Atherosclerosis (I70.9) 9 Advanced age (R54) 10 Cardiac arrhythmia (I49.9) c. d. Part II Advanced age (R54) Congestive heart failure (I50.2) Atherosclerotic coronary artery disease (I25.1) Coronary artery disease (I25.1) Acute myocardial infarction (I21.9) Heart failure (I50.9) Atherosclerotic coronary artery disease (I25.1) Table 1. Table of possible sequences for the death certificate for the sample case with corresponding ICD-10 codes. ANALYSIS To determine if physicians incorrectly code COD in patients who die of undetermined natural causes, the percentage of survey respondents who correctly used an R code (R0011 R99) was calculated. The two survey versions (open-ended responses vs specific choices) were compared to determine differences by survey format using a chi square test. Responses were categorized into 17 possible categories (15 leading causes of death, all other causes of death, and R00-R99) and further collapsed into two categories: Nonspecific (R codes) and Specific (other than R codes). Coding of the text of the conditions/diagnoses listed by the physician into ICD-10 codes was performed using the MMDS (CDC/ National Center for Health Statistics, 2010) software. For both survey versions (A and B), the responses for the COD were entered and processed with the SuperMICAR and MICAR200 programs, which are the first two programs in the MMDS software. The output of these two programs is the ICD codes for each of the conditions/diagnoses entered in Parts I and II on the COD. All coding done in this manner by the software was individually reviewed by the author, and no discrepancies were noted between what the physician entered and the descriptions of the ICD diagnosis codes generated by the software. For both survey versions, the last condition or diagnosis (the first if only one is listed) chosen by the physician for item 32, part I was recorded as a new variable, the physiciandetermined underlying COD. This physician-determined underlying COD is in keeping with the death certificate instruction directing the physician to “Enter the UNDERLYING CAUSE (disease or injury that initiated the underlying events resulting in death) LAST.” 12 Survey responses for the completion of the death certificate were processed using the MMDS software to generate the software-generated underlying COD. Underlying COD (both physician-determined and software-generated) were grouped into broad categories based on the WHO ICD-10 classification (see Table 1). These categories are based on the 15 leading causes of death for the total population of the US in 2006 (Heron, Hoyert, Murphy, Xu, Kochanek, & Tejada-Vera, 2009) with the additional categories of deaths coded to Chapter XVIII of the ICD-10—Symptoms, signs and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings, not elsewhere classified (ICD–10 codes R00–R99), plus a category for any residual. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS version 9.2 statistical software. (SAS Institute, 2010) Descriptive characteristics (specialty, prior death certificate training, resident/intern status, years since medical school graduation) were reported. Because it was thought that specific physician characteristics might influence their selection of undetermined natural causes as a single cause of death, these characteristics were also compared to the use of choosing a non-speciifc cause. In order to test whether the format of the question affected physician responses, the proportion of physician reportiong nonspecific causes was compared between those who received the open-ended format (A) and those who received the coded-ended format (B). Then, odds ratios with confidence intervals were also calculated to determine the likelihood of a COD reflecting uncertainty, which was defined as a diagnosis coded to R00-R99. 13 Physician-determined and software-generated underlying cause of death categories for each survey group based on the WHO ICD-10 classification were also compared. Agreement between the orginal responses and those obtained from the coding software were compared with a kappa coefficient. RESULTS Of the 70 physicians contacted, 42 participated, for a 60% response rate. Two surveys Characteristic Total Survey Version A B Specialty FP IM Years Since Medical School Graduation 0-10 11-20 21-30 >30 Training Status Intern/Resident Not in training program Prior Death Certificate Training Yes No n (%) n (%) of Physicians in Group Using a R Code as Underlying COD 40 (100) 25 (62.5) 21 (52.5) 19 (47.5) 11 (52) 14 (74) 32 (80) 8 (20) 20 (62.5) 4 (50) 12 9 12 7 11 (92) 3 (33) 6 (50) 5 (71) 8 (20) 32 (80) 8 (100) 17 (53) 2 (5) 38 (95) 1 (50) 24 (63) Table 2. Survey responders’ characteristics and use of R code for underlying COD 14 were incomplete, and were not included in the analysis. 80% identified their primary specialty as Family Practice (FP), and the remainder were Internists (IM). 20 % were FP residents from the local training program. Only 5% of all the responders reported having received any death certificate completion training (only 9% of the Family Practitioners and none of the Internists had prior death certificate training). Years since medical school for all responders ranged from 2 to 61, with a mean of 19.4. Table 2 presents this data in further detail. There were a nearly equal number of responses for each version of the survey (A=21, B=19). Table 3 shows the distribution of responses by ICD category for each group. Of the 17 possible COD categories, the respondents utilized relatively few ICD categories for the underlying cause of death in this study, which is not unexpected given the paucity of signs and symptoms in the sample case. The data in table 3 was grouped into two general categories for analysis based on whether they were coded to ICD-10 Rcodes: Nonspecific (R00-R99) and Specific (other than R00-R99). The overall physician-determined and software-generated underlying COD were in agreement only 65% of the time (κ= .37). Overall, 62.5% (25/40) of physicians reported the underlying COD correctly as “Nonspecific” (see Table 4). However, fewer physicians coded for nonspecific causes in the open-ended format (52%) than when they had a list of possible causes (74%). 15 ICD-10 Description I00-I09, Diseases of the heart I11,I13,I20-I51 C00-C97 Malignant neoplasms I60-I69 Cerebrovascular diseases J40-J47 Chronic lower respiratory diseases Open format (version A) n (%) Structured format (version B) n (%) Physiciandetermined Softwaregenerated Physiciandetermined Softwaregenerated 6 (29) 9 (43) 4 (21) 15 (79) - - - - 1 (5) 1 (5) 1 (5) 1 (5) - - - - V01-X59, Y85- Accidents (unintentional Y86 injuries) - - - - E10-E14 Diabetes mellitus - - - - G30 Alzheimer’s disease - - - - J10-J18 Influenza and pneumonia - - - - N00-N07, N17- Nephritis, nephritic N19, N25-N27 syndrome and nephrosis - - - - A40-A41 - - - - U-3, X60-X84, Intentional self-harm Y87.0 (suicide) - - - - K70, K73-K74 Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis - - - - I10, I12, I15 Essential hypertension and hypertensive renal disease - - - - G20-G21 Parkinson’s disease - - - - U01-U02, X85Assault (homicide) Y09, Y87.1 - - - - 11 (52) 8 (38) 14 (74) 3 (16) 3 (14) 3 (14) - - 21 (100) 21 (100) 19 (100) 19 (100) R00- R99 Septicemia Symptoms, signs and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings, not elsewhere classified All other causes (residual) Totals Table 3. Physician-determined and software-generated underlying cause of death categories for each survey group based on the WHO ICD-10 classification. Although the effect size was large (74% - 52% = 22%; OR 0.39, 95% CI 0.10-1.49), the Chi square analysis showed no statistical difference between the rates for responders 16 given version A over version B [χ2 (1, N = 40) = 1.932, p = 0.165] due to the small sample size. Open format (version A) Structured format (version B) Nonspecific (R00-R99) 11 (52%) 14 (74%) Specific (non-R code) 10 (48%) 5 (26%) Table 4. Physician-Determined Underlying COD. X 2 (1, N = 40) = 1.932, p = 0.165 After processing with the MMDS software, only 27.5% (11/40) of the respondents’ original death certificates were coded correctly as non-specific causes. Table 5 shows that the odds of the software-generated underlying COD being “Nonspecific” was higher in version A (38%) than in Version B (16%), although this was not significant [χ2 (1, N = 40) = 2.489, p = 0.115]. Again, the large effect size (16% difference or OR 3.9, 95% CI 0.7 - 14.9) was not significant due to the small sample size. Open format (version A) Structured format (version B) Nonspecific (R00-R99) 8 (38%) 3 (16%) Specific (non-R code) 13 (62%) 16 (84%) Table 5. Software-generated underlying COD. X 2 (1, N = 40) = 2.489, p = 0.115. Table 6 shows that the physician and MMDS software agreement on the underlying COD was 65% and the kappa only fair (κ= 0.37). In this study, all transformations by the MMDS software from the physician-determined 17 κ= 0.37 Software-Generated Underlying COD PhysicianDetermined Underlying COD Nonspecific (R00-R99) Specific (Non-R Code) Nonspecific (R00-R99) 11 14 Specific (Non-R Code) 0 15 Table 6. Software-generated underlying COD specificity versus that determined by the physician. to the software-generated underlying COD category were from nonspecific R codes to the category of heart disease (I00-I09, I11, I13, I20-I51). These changes occurred in 14 of the 25 cases (56%) in which an R code was used by the physician as the underlying COD. Table 7 shows the statistically significant increase in heart disease reported by the Underlying COD Category Physician-Determined n (%) Software-Generated n (%) Diseases of the heart (I00-I09, I11,I13,I20-I51) 10 (25%) 24 (60%) All others 30 (75%) 16 (40%) Table 7. Comparison of heart disease diagnosis as the underlying COD category. MMDS software to that of the physician (OR 4.5, CI 1.7313 - 11.6962). To find out if physician characteristics were associated with the use of the nonspecific classification, the physician characteristics in Table 2 were compared by using Fisher’s exact test. There were no statistical differences between responses by specialty (p=1), years since medical school graduation (p=.75), or prior death certificate training (p=1). There was a significant increase (p=.02) in nonspecific R code usage among physicians in training (intern/resident) compared with those not in training. 18 DISCUSSION The first question that this study attempted to answer was whether physicians code for uncertainty in the underlying cause of death when the cause is unclear. This study shows that overall, 62.5% of physicians used a nonspecific R code for the underlying COD. The remainder chose a specific diagnosis, suggesting physician reporting may be biased toward listing a specific disease or diseases rather than nonspecific or unknown causes when uncertain about the actual cause of death. Secondly, this study attempted to answer whether physicians would be more likely to choose an uncertain/nonspecific condition as the underlying COD when given the option, as in the specific COD sequences in Version B that included uncertain/nonspecific diagnoses. There was a tendency for physicians to use these nonspecific diagnoses more in Version B than with the open-ended format of Version A, although these differences failed to obtain statistical significance due to the low number of respondents. These results also suggest that while the majority of physicians may code for an underlying COD category of not elsewhere classified (R00-R99) for a person dying of undetermined natural causes, software used for analysis of the death certificate for national statistical reporting may be biased to report the underlying COD category for these death certificates as heart disease (I00-I09, I11, I13, I20-I51). Although 62.5% of physicians reported a nonspecific underlying COD, only 25% appeared to report a 19 nonspecific COD after MMDS software transformation. Approximately half of the original nonspecific CODs were transformed into specific CODs by the software. To illustrate how this could occur, consider the following coding of the death certificate (Fig. 4): Fig. 4. Single cause of death without other significant conditions. The above is the coding suggested by the CDC for the case used in this study. The MMDS software would code the underlying COD for this death certificate as R99 - Other Ill-Defined and Unspecified Causes of Mortality. Now consider the equally plausible cause of death coding for the same case (Fig. 5): 20 Undetermined Natural Causes Coronary Artery Disease Fig. 5. Cause of death with significant contributing condition in Part II. Here the physician only adds the coronary artery disease seen at autopsy to Part II. The physician-determined COD remains R99; however, the MMDS software now codes the underlying COD as I25.1 - Atherosclerotic Heart Disease, and this is the code that would be used for national statistical purposes had this been an actual death certificate. The 2006 National Mortality Data (CDC/National Center for Health Statistics, 2009) shows only a 2.9% difference between the top two causes of death – heart disease and cancer. Considering that 25% of physicians in this study chose heart disease as the underlying cause of death for the study case, and considering the bias shown for the MMDS software to report the underlying cause of death as heart disease, one begins to wonder about the larger ramifications of erroneous cause of death reporting in terms of public health initiatives, actuarial and insurance-related issues, and dollars spent on healthcare and research. 21 In conclusion, the results of this pilot study need to be confirmed with a larger sample size, but this study suggests that heart disease may be over-reported as the underlying COD, even when the physician makes a reasonable effort to code an uncertain COD using nonspecific R codes. Whether national statistics for cause of death would be significantly affected by better coding for uncertainty by physicians (and computer software) remains to be seen. 22 BIBLIOGRAPHY Brown, D. L., Al-Senani, F., Lisabeth, L. D., Farnie, M. A., Colletti, L. A., Langa, K. M., et al. (2007). Defining Cause of Death in Stroke Patients. The Brain Attack Surveillance in Corpus Christi Project. American Journal of Epidemiology , 165 (5), 591-596. CDC/National Center for Health Statistics. (1997, January). Retrieved February 7, 2010, from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/death_certification_problems.htm CDC/National Center for Health Statistics. (2009, April 17). National Vital Statisics Reports, Vol 57, No 14 pg. 119. Retrieved March 1, 2010, from http://www.cdc.gov/NCHS/data/nvsr/nvsr57_14.pdf CDC/ National Center for Health Statistics. (2009a, September 1). ICD-10 - International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision. Retrieved July 15, 2010, from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd10.htm CDC/ National Center for Health Statistics. (2010). Mortality Medical Data System Version 2010.10. Hyattsville, MD. CDC/ National Center for Health Statistics, Division of Vital Statistics. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC. (2003, April). Physician Handbook on Medical Determination of Death. Retrieved February 22, 2010, from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/misc/hb_cod.pdf Heron, H. P., Hoyert, D. L., Murphy, S. L., Xu, J. Q., Kochanek, K. D., & Tejada-Vera, B. (2009). Table B in Deaths: Final Data for 2006. National Vital Statistics Reports. National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD. James, D. S., & Bull, A. D. (1996). Information on death certificates: cause for concern? Jounal of Clinical Pathology, 49, 213-216. Lakkireddy, D. R., Gowda, M. S., Murray, C. W., Basarakodu, K. R., & & Vacek, J. L. (2004). Death Certificate Completion: How Well Are Physicians Trained and Are Cardiovascular Causes Overstated? American Journal of Medicine, 117, 492-498. Maudsley, G., & Williams, E. M. (1996). 'Inaccuracy' in death certification - where are we now? Journal of Public Health Medicine, 18 (1), 59-66. National Center for Health Statistics. (2010, January). Instructions for Classifying the Underlying Cause-of-Death, ICD-10, 2010, Part 2a. Retrieved March 29, 2010, from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/dvs/2A_2010acc.pdf SAS Institute. (2010). SAS Version 9.2. Cary, NC. SAS Institute. 23 Tavora, F., Crowder, C., Kutys, R., & Burke, A. (2008). Discrepancies in initial death certificate diagnoses in sudden unexpected out-of-hospital deaths: the role of cardiovascular autopsy. Cardiovascular Pathology , 17, 178-182. World Health Organization. (1992). International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. 24 APPENDIX 25 SURVEY VERSION A 26 Dear physician, Thank you for taking the time to complete this survey. Please return the completed survey in the enclosed self-addressed stamped envelope or directly to the investigator. The address for return is: David B. Trant, M.D. 3507 La Reforma Baytown, TX 77521 713 252-6725 If you wish to receive a summary of the results of this study, please let me know. Again, thank you for your time. 27 Please take a few minutes to fill out this survey on the death certificate completion. This survey should take about 5-10 minutes. Your answers will be kept confidential. Thank you for your participation. Sample Case A 92-year-old male was found dead in bed. He had no significant medical history. Autopsy disclosed minimal coronary disease and generalized atrophic changes commonly associated with aging. No specific cause of death was identified. Toxicology was negative. 1) Cause of death determination. Please complete item 32, Parts I and II, of the following portion of a death certificate for the sample case above (ignore grayed-out portions): Please turn to the next page. 28 Additional Questions 2) What is your primary medical specialty? Family practice Internal medicine Other (specify): ____________________________ 3) How many years has it been since you completed medical school? 4) Are you currently in an internship/residency training program for your specialty listed above? Yes No 5) Have you ever had any formal training in death certificate completion? Yes No 6) How comfortable do you feel completing death certificates? Very comfortable Somewhat comfortable Neither comfortable or uncomfortable Somewhat uncomfortable Very uncomfortable 29 7) The following questions deal with death certificates in general, not the previous sample case. For the following diseases or conditions, please answer yes or no as to whether (in your opinion) this condition would ever be acceptable as a single cause of death on the death certificate, without listing any additional causes or conditions. Disease or Condition Yes No Cardiopulmonary Arrest Acute Myocardial Infarction Undetermined Natural Causes Cerebrovascular Accident (CVA) Motor Vehicle Accident (MVA) Cardiac Arrhythmia Respiratory Failure Hypertension Advanced Age Thank you for taking the time to complete this survey. 30 SURVEY VERSION B 31 Dear physician, Thank you for taking the time to complete this survey. Please return the completed survey in the enclosed self-addressed stamped envelope or directly to the investigator. The address for return is: David B. Trant, M.D. 3507 La Reforma Baytown, TX 77521 713 252-6725 If you wish to receive a summary of the results of this study, please let me know. Again, thank you for your time. 32 Please take a few minutes to fill out this survey on the death certificate completion. This survey should take about 5-10 minutes. Your answers will be kept confidential. Thank you for your participation. 1) Cause of death determination. Please consider how you would complete the cause of death portion of the death certificate for the sample case on the next page. While the choices may not reflect exactly the way you would complete the death certificate, please choose from the table on the next page what you feel is the single, most appropriate scenario for completing the Cause of Death, item 32 Parts I and II from the list on the next page (ignore grayed-out areas). EXAMPLE: If you were to choose Scenario #99 in the table below, Scenario # 99. Item 32, Part I a. b. Acute Rupture of myocardium myocardial infarction c. d. Coronary artery Atherosclerotic thrombosis coronary artery disease the death certificate would be completed as: Rupture of myocardium Acute myocardial infarction Coronary artery thrombosis Atherosclerotic coronary artery disease Diabetes, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, smoking Please turn to the next page. 33 Part II Diabetes, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, smoking Sample Case A 92-year-old male was found dead in bed. He had no significant medical history. Autopsy disclosed minimal coronary disease and generalized atrophic changes commonly associated with aging. No specific cause of death was identified. Toxicology was negative. Please choose the scenario number from the table below that you feel is the single, most appropriate scenario for completing the Cause of Death on the death certificate for the sample case above (see instructions on previous page): Scenario # Scenario # Item 32, Part I a. b. 1 Acute cerebrovascular accident 2 Cardiac arrhythmia Atherosclerotic coronary artery disease 3 Cardiac arrest Undetermined natural causes 4 Undetermined natural causes 5 Respiratory arrest 6 Undetermined natural causes 7 Acute myocardial infarction Atherosclerotic coronary artery disease 8 Ruptured cerebral aneurysm Atherosclerosis 9 Advanced age 10 Cardiac arrhythmia c. d. Part II Advanced age Congestive heart failure Atherosclerotic coronary artery disease Coronary artery disease Acute myocardial infarction Heart failure 34 Atherosclerotic coronary artery disease Additional Questions 2) What is your primary medical specialty? Family practice Internal medicine Other (specify): ____________________________ 3) How many years has it been since you completed medical school? 4) Are you currently in an internship/residency training program for your specialty listed above? Yes No 5) Have you ever had any formal training in death certificate completion? Yes No 6) How comfortable do you feel completing death certificates? Very comfortable Somewhat comfortable Neither comfortable or uncomfortable Somewhat uncomfortable Very uncomfortable 35 7) The following questions deal with death certificates in general, not the previous sample case. For the following diseases or conditions, please answer yes or no as to whether (in your opinion) this condition would ever be acceptable as a single cause of death on the death certificate, without listing any additional causes or conditions. Disease or Condition Yes No Cardiopulmonary Arrest Acute Myocardial Infarction Undetermined Natural Causes Cerebrovascular Accident (CVA) Motor Vehicle Accident (MVA) Cardiac Arrhythmia Respiratory Failure Hypertension Advanced Age Thank you for taking the time to complete this survey. 36 Vita David B. Trant was born in Texas, where he has lived for all of his 51 years except for 6 months in Iraq in 2008 with the military. He is a Baylor University graduate, followed by a Doctor of Medicine degree from UTMB. Following a residency in Internal Medicine from Scott & White Hospital, he practiced in Baytown, TX for 20 years before joining the US Air Force in 2007 as a Flight Surgeon. He is currently completing a Residency in Aerospace Medicine (RAM) at BrooksCity Base, TX. Permanent address: 101 Valona Dr., Cibolo, TX 78108 This dissertation was typed by the author. 37