NJNNSTOY TL Position Paper - National Network of State Teachers

advertisement

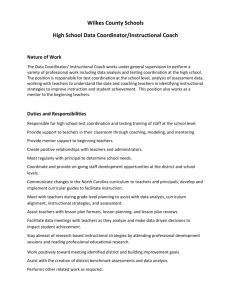

1 The Critical Contribution of Teacher Leadership in Influencing Reform Initiatives to Transform Practice, Policy and the Profession: Moving from “Nice to have” to “Need to have” A Position Paper Written and Presented by the New Jersey Chapter, National Network of State Teachers of the Year (NNSTOY): Kathleen Assini Diane Cummins Jeanne DelColle Robert Goodman Danielle Kovach Jeanne Muzi Peggy Stewart Maryann Woods-Murphy November 6, 2014 2 Teacher leadership means having a voice in the policies and decisions that affect your students, your daily work, and the shape of your profession. -U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan Within every school there is a sleeping giant of teacher leadership, which can be a strong catalyst for making change. -Marilyn Katzenmeyer & Gayle Moller Who knows better than educators what happens in highly effective classrooms? -Katherine Bassett, NNSTOY Executive Director Alone we can do so little, together we can do so much. -Helen Keller 3 The Critical Contribution of Teacher Leadership in Influencing Reform Initiatives to Transform Practice, Policy and the Profession: Moving from “Nice to have” to “Need to have” The Current Culture of Schools The 2014-15 school year has begun and educators across New Jersey are once again seeking ways to balance the enormous responsibilities of their profession. During the past school year, teachers and administrators experienced a myriad of new initiatives, mandates and policies, including a new evaluation system, new domain rubrics, SGOs, SGPs, formal and informal observations, evidence collection requirements and submission deadlines. For teachers, it was a year of competing commitments, duties and responsibilities. They worked to preserve their passion for teaching and learning as they met the challenges of new accountability measures, assessment procedures, systems and regulations. They learned about new evaluation expectations and how they are required to demonstrate their proficiency through various means, while at the same time: Investing time individualizing lessons for their students’ strengths and challenges. Participating in professional learning opportunities focused on the Common Core State Standards and integrating new technology. Communicating with families about assessments, school safety and other issues Immersing themselves in student data in order to design instruction to drive achievement. It has been a monumental task for every New Jersey teacher. For many principals, supervisors and administrators, it was a year of multiple educator evaluations, pre- and post-observation conferences and relentless record keeping, leaving little time to focus on building community, strengthening practitioner skills, supporting new teachers 4 or developing instructional leadership. Administrators across the state, not satisfied to simply manage day-to-day school activities, yearned to hone their skills as instructional “Lead Learners,” but were pulled in other directions. New Jersey teachers and administrators alike saw significant changes and additions to their professional responsibilities. Many suffered from “initiative overload” as they waded through information and directives for Common Core State Standards (CCSS), new teacher and principal evaluation requirements, new professional development and mentoring regulations, new technologies and requirements for data collection, evidence verifications and portfolio uploads. The overwhelming nature of the current climate is taking a worrying toll on morale. The 2013 Met Life Survey of the American Teacher reported that both teacher and principal satisfaction has decreased to the lowest level in 25 years. At this time of unparalleled demands on teachers and administrators, it is evident that a change in direction is needed. For the ambitious goals of New Jersey’s recent reform initiatives to be successful, a culture of sustainable, solution-driven teacher leadership must be intentionally and purposefully integrated into educational policy decision-making. Teacher Leaders, actively influencing practice and policy, is the only way we can achieve enhanced teaching practices and advance the teaching profession. The Need for Teacher Leadership In 2004, Jennifer York-Barr and Karen Duke wrote, “Teacher leadership is the process by which teachers, individually or collectively, influence their colleagues, principals, and other members of the school community to improve teaching and learning practices with the aim of increased student learning and achievement.” As the term “Teacher Leader” has become 5 recognizable in districts and schools across the nation, many teachers have found themselves in a wide variety of roles, both formal and informal. Teacher Leadership (TL) provides teachers with opportunities beyond the classroom to strengthen practice, influence policy and elevate the profession. It is an important means to increase practitioner expertise, foster communication within a school community, implement new curricular initiatives and share leadership with administration. Resources, such as the Teacher Leader Model Standards (2011), provide additional structure and understanding about how to establish TL roles and clarify expectations. For example, the standards say, “Teachers teach more effectively when they work in professional cultures where their opinions and input are valued. In such environments, administrators support teachers as they exchange ideas and strategies, problem-solve collaboratively, and consult with expert colleagues.” The U.S. Department of Education (USDOE) recognizes the integral role TLs play in our schools. In March 2014, Secretary of Education Arne Duncan introduced a major USDOE initiative called Teach to Lead, which seeks to improve student outcomes by expanding opportunities for TL, particularly those approaches that allow teachers to lead from the classroom. Secretary Duncan has expressed his desire to support TL, “whether that means a stronger voice in policy, or a stronger role in guiding your profession and your newer colleagues.” He recognizes what teachers know instinctively: teachers’ voices and expertise are vital to creating learning cultures that benefit students, schools and the profession. TLs across the country are fostering this solution-driven approach by creating hybrid roles, developing curriculum and creating projects to support both students and their colleagues. But too often such leadership is seen as a “nice” addition to a school community rather than a 6 necessary component for its success. So, for example, when a teacher takes over scheduling for the principal or demonstrates a teaching technique for novice teachers, that effort is appreciated, but often not replicated or integrated. Undoubtedly, those occasional, informal efforts are great for the schools, teachers and students who benefit from the TL’s expertise. But because such leadership is not perceived as necessary and worthy of investment, those benefits can be limited and fleeting. In the current educational climate, it is evident that in order to support all of our students, recruit and retain effective teachers, and increase student achievement, we must abandon the status quo of an out-of-date, hierarchical educational system. Concrete steps must be taken to incorporate TL into all facets of education, because it is the essential component missing from the flood of reform measures being implemented across the state. In fact, it is the one straightforward, practical solution that can transform our education system by improving practice, influencing policy and advancing the profession. TL is the commonsense catalyst to drive and sustain thoughtful, research-based education reform initiatives. It is an effective vehicle for generating, leveraging and sustaining innovation in districts, schools and classrooms, and is necessary for successful policy implementation and educator evaluation. Teacher Leadership and Evaluation As noted earlier, teachers are not the only ones struggling to keep instruction at the center of their work. The expansive new evaluation initiative introduced during the 2013-14 school year has profoundly changed how principals, assistant principals, supervisors, administrators and instructional coaches utilize their time. Meeting the requirements of the new system has meant placing a priority on conferences and observations, severely limiting the time available to invest 7 in other critical areas, including new teacher induction, Professional Learning Community (PLC) development and coaching for best practices. In 2013, Rachel Curtis wrote an Aspen Institute research report titled “Finding a New Way: Leveraging Teacher Leadership to Meet Unprecedented Demands.” She observed, “A common challenge facing school systems is the implementation of new teacher evaluation systems that emphasize multiple observations and frequent feedback. Evaluations with meaningful and actionable feedback are a great asset to teachers, especially as they aim to implement the Common Core, but they also represent one of the greatest demands on principals’ time. As it is, employee-to-evaluator ratios are much greater in education than in the private sector. Engaging teacher leaders as peer observers and coaches could ameliorate the burden on principals and maximize the likelihood that evaluation will realize its potential to drive teacher growth and development.” By expanding teacher roles and responsibilities, a professional culture is strengthened so that every student can learn and achieve. In 1992, Paul Ramsden boldly stated, “The ultimate guardians of excellence are not external forces, but internal professional responsibilities.” Building professional partnerships and cultivating shared leadership will benefit every member of a school community. TLs will support principals, supervisors and administrators by helping to make a challenging workload, with an intense set of responsibilities, more manageable. Integrating a system that utilizes the talents, experience, knowledge and resources of TLs will have both short-term and long-term benefits. TLs can build mutually beneficial teacher-toteacher relationships and thus maximize the impact of induction, mentoring, coaching and support of new and novice teachers. That should significantly improve teacher retention. Under the guidance of TLs, new teachers will learn the value of working collaboratively and developing 8 learning-focused classroom environments that support active and engaged participation. TLs can provide actionable feedback serving as: Peer coaches. Advocates for positive behavior support systems. Advisors and guides for Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) initiatives and technology integration. Catalysts for developing essential higher order thinking skills. The opportunities for TLs to benefit schools are nearly limitless. They can assist in reconceptualizing how time is utilized during the school day and help look at schedules and calendars in new ways. They can shape policy decisions and help implement changes that support innovation. Teachers, administrators and students will benefit from the multiple perspectives and points of influence TLs provide to every learning community once their role is fully integrated, utilized and respected. Teacher leadership in New Jersey already has established roots. Effective, scalable models exist across the state and nation with New Jersey teachers already leading in many capacities, including: A teacher guiding policymakers as a Washington DC Teaching Ambassador Fellow working with the U.S. Department of Education. A teacher housed at the N.J. Department of Education and creating Teacher Advisory Panels to provide teacher perspectives on new initiatives. An assistant superintendent (former teacher) building collaborative PLC time into an innovative daily schedule, successfully creating time for teachers to share, coach and support each other. 9 Teachers providing-job embedded professional learning opportunities in schools, colleges and organizations, mentoring new teachers and presenting technology workshops for colleagues. Teachers creating curriculum materials and training other teachers in a variety of methodologies while sharing research and resources. Teachers leading from the classroom and developing proposals for hybrid roles of teaching students part time and fortifying novice teacher skills as instructional coaches part time. Teachers rethinking technology integration by collaborating with colleagues on project based, technology infused projects that connect students to each other and to a larger world. Teachers empowering parents as partners through the creation of parent academies that provide parents with the skills they need to increase their children’s literacy and math skills beyond the school day. There are other replicable examples of New Jersey teacher leadership in action. These expanded teaching roles and responsibilities are vital to sustaining the profession and partnering with all the stakeholders whose priority is student learning, especially as complex content, coursework and standards continue to be integrated into all classrooms from preschool through high school, and beyond. Teacher Leadership and the Common Core One of the greatest challenges currently facing school districts is implementing the rigorous Common Core State Standards. Teachers face substantial changes in both curriculum requirements and instructional methods. They are challenged to incorporate new assessments 10 and materials into their work. TLs are the key ingredient in strengthening CCSS knowledge and advancing student success. In her Aspen Institute report, Curtis wrote, “One challenge confronting virtually every system is the transition to Common Core standards. There is no reasonable chance of meeting these expectations without engaging many more teachers in leading this work. Facilitating professional learning, specializing in difficult and highly valued instruction, freeing up time of principals and other administrators: all these could advance both teacher leadership and Common Core implementation.” If districts put a laser focus on incorporating TL into CCSS implementation, as well as teacher development and student achievement, innovation can be cultivated across learning communities, changing the status quo into successful educational experiences for every student. Shared leadership and purpose will enable teachers to influence instructional decisions, support the skillful growth of peers and establish career paths to ensure personal and professional advancement. All of that will led to better retention of high quality, knowledgeable, passionate teachers. Marcel Proust wrote, “The voyage of discovery is not in seeking new landscapes but in having new eyes.” The time has come to look at TL with new eyes and see the tremendous opportunity for TL to drive system-wide innovation, increase student achievement and enhance practitioner professionalism. It is no longer acceptable to view TL as merely a “nice” addition to a school or district. It is an essential element for successfully implementing educator evaluation, thoughtful reform initiatives and smart education policy. It is also a vital tool for strengthening student achievement and enhancing teacher induction and retention. 11 Curtis stated in her paper, “The promise lies in defining the processes that are most critical to student learning and then designing teacher leadership in service of them.” The time to do that is now. Therefore, the members of the NJ Chapter of the National Network of State Teachers of the Year (NNSTOY) recommend the following steps be taken immediately: 1. Teachers: Actively design TL proposals to initiate/promote/support Teacher Leadership in your school, district, and beyond. Look for opportunities to lead from your classroom, foster a collaborative school culture and share current educational research in order to enhance teaching effectiveness and student learning. Advocate for, design and implement meaningful, job-embedded professional learning experiences so all teachers are learning and growing. 2. Administrators: Seek out Teacher Leaders within your schools and districts to mentor and support novice teachers and facilitate a range of effective professional development initiatives. Incorporate innovative schedules/routines into the days and weeks of the school year to enable TLs to work as instructional coaches, meet with colleagues to understand data, plan student interventions and develop hybrid roles. This will enable TLs to creatively use their knowledge and experience to improve teaching and learning. 3. Policy Makers: Promote Teacher Leadership as a necessary component of current educator reform initiatives: Establish a Teacher Leadership Exploratory Consortium at the New Jersey Department of Education (NJDOE) that would include stakeholders from NJPSA, NJASA, NJEA, UFT, NNSTOY, and other partners, to provide guidance, resources, TL training and conduct research on the impact of TL in student learning. 12 Build upon the NJDOE’s recent decision to utilize the unique knowledge and abilities of effective teachers (as evidenced by the establishment of the Achievement Coaches grant) and create a NJDOE framework for including TLs as committee members and liaisons to NJDOE departments. Bring educator perspective and knowledge into policy decisions by including TLs in discussions, meetings and conferences focused on AchieveNJ programs, plans and projects. 13 Resources: Curtis, Rachel. "Finding a New Way: Leveraging Teacher Leadership to Meet Unprecedented Demands." Aspen Institute. 2013 "Home." Teacher Leader Model Standards. Web. 22 Oct. 2014. "MetLife Survey of the American Teacher." MetLife Foundation. Web. 24 Oct. 2014. "Paul Ramsden." Paul Ramsden Blog. Web. 20 Oct. 2014. “What Do We Know About Teacher Leadership? Findings From Two Decades of Scholarship.” Review of Educational Research. Vol. 74, No. 3. (1 January 2004), pp. 255-316, by Jennifer York-Barr, Karen Duke "Why Teach to Lead?" Teach to Lead. USDOE. Web. 23 Oct. 2014.