Gutenberg Printing Press: World History Lesson Plan

advertisement

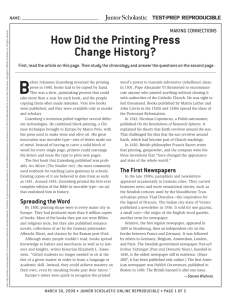

ELL High School Social Studies: World History (Grade 10+) Standard: People, places and environment 1.3 Resource: Name: Growth is caused by printing press, paper manufacture. Johannes Gutenberg and the Printing Press http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y1vl2j24Mtk Unit Objectives: Learn when the printing press was first used in Europe Understand how the printing press enabled the “dissemination of knowledge.” Be able to watch and indentify main ideas from the first 10 minutes of Johannes Gutenberg and the Printing Press. (Video) Compare printing technology in Europe and your native country at the time of Gutenberg. Procedure: 1. Look up the definitions of words on the vocabulary list for this unit in your own native language. Write the definitions (in your native language) beside each English word. 2. Form groups and take a pre-test about the Gutenberg printing press. 3. Do a web quest: Find some pictures of books that were printed on the original Gutenberg printing press. Find out how much some of these books cost now. Make a power point. For centuries, the dissemination of knowledge through books had been only for the few, reserved largely for monks and priests. Each book was a priceless one-off. For most people in the middle ages, this was an academic problem. They couldn’t read or write, anyway. During the middle ages, books were written out by hand, mostly in monasteries. Often the monks would spend years on a work. Then in 1450, an invention changed the world. In the German city of Mainz, Johannes Gutenberg invented the technique of printing with movable type. This made it possible to duplicate books in large numbers, and at relatively low cost. The technological foundation was laid for the intellectual, political, and religious changes of the succeeding centuries. Johannes Gentz Fleich, who later changed his name to Gutenberg, was born in Mainz in around 1400. His father was a wealthy merchant. Young Johannes attended the monastic ELL High School Social Studies: World History (Grade 10+) school in Mainz. That much we know. But then his trail goes cold for a while. We only pick it up again in Strasburg, where he settled in 1434. Here, he set up a factory that produced mirrors for pilgrims. There were very popular among the faithful, who hoped thereby to capture something of the charisma emanating from the shrine that they were visiting, and from the relics it contained. For Gutenberg, it was a lucrative business. There was a flourishing trade in devotional objects. Particularly popular were woodcuts depicting the saints. Woodcut is one of the earliest printing techniques, but it only reached Europe in the early middle ages. Here is served primarily for the dissemination of pictures and texts. But cutting these whole page blocks was a time consuming process. First, a mirrorimage of the hand written page has to be drawn on the block. Then, the individual letters have to be carved out. Finally, the block is inked in, and a sheet of paper was laid on top, and rubbed hard with a bone tool so that it takes up the ink. By the start of the fifteenth century, more and more of these page prints were coming onto the market. Occasionally, a number of pages were bound into a book. The trade in these books also gave a boost to manuscript production. Manuscripts had long since ceased to be the exclusive reserve of the monasteries. Secular scribes were doing good business. The establishment of the first universities had created a great demand for books. Libraries were founded, making knowledge in the form of books accessible. Books needed to be cheaper and more quickly available. But that wasn’t all. In particular, scholars wanted uniform copies. A new production technique was feverishly sought after – and one of the seekers was Gutenberg. In 1446, he returned to Mainz. Here, he found solid financial backers, allowing him to go ahead with his enterprise. His breakthrough came with a brilliant idea. He broke up his text into its constituent parts: letters, punctuation marks, and frequent combinations known as ligatures. These were then combined to form the blocks for printing words, lines, and pages. The characters were cast, and could be used in new combinations time and again. A character is produced as follows: on the end of a metal rod, a mirror-image of the letter is engraved. This is then pushed into softened copper, producing a pit in the shape of the letter. This matrix, as it’s called, acts as the mould for the actual type, which is cast from lead. In order to manufacture the many letters needed quickly and in sufficient quantity, Gutenberg took another important step forward. He invented the hand casting instrument. It ELL High School Social Studies: World History (Grade 10+) consists of a rectangular channel. The matrix is inserted at one end, and molten lead poured into the other. When the instrument is opened, a letter cast in lead is ready to be used. As the matrix is reusable, an unlimited number of identical letters can be cast. Finally, the type-setter can begin to combine the letters into lines. In the “form”, the lines of columns are combined to create the page layout as designed. The result is a mirror-image of the page to be printed. The form is now inked in with printer’s ink. Gutenberg used a mixture of lamp----, varnish, and egg white. Printing can now start. Gutenberg used a special press for this purpose, and he derived the principal from the traditional wine press. Gutenberg’s first printed works were official documents: papal decrees, and grammars. But soon, he started on a mammoth venture – the Latin bible. For this project he cast more than a hundred-thousand pieces of type. For more than two years, Gutenberg’s type-setters and printers worked on the first edition of 180 copies. The text was printed in black-letter or Gothic type, based on the handwriting of the day. Finally, the illuminator added the colored initials and drawings. With his bible, one of the world’s most beautiful printed books, Gutenberg proved that a work printed with movable type could be as aesthetically pleasing as one written by hand. The edition was soon sold out. Gutenberg’s contemporaries were impressed. It was the first time a work had been available in such a large edition, and every copy was identical. The written word now had authoritative status. Knowledge of this revolutionary technology was quick to spread. Soon, the first printing presses were set up in Cologne, Bamberg, and Basal. In Venice, an enterprising publisher named Algus Manutius, began to print the works of the classical authors. His clientele comprised of all of Europe’s humanistic intellectually elite. Manutius employed the most talented printers of the age. They developed the typeface known as Antigua, which soon spread throughout Europe. 20 years after Gutenberg’s invention, the new technology was firmly established. Thousands of titles were marketed in editions of up to one thousand. Books now became affordable for ordinary people. As society became more literate, the number of potential readers increased. ELL High School Social Studies: World History (Grade 10+) Dissemination accessible. the few, uniform copies. monks priests. sought after – priceless seekers. one-off. financial backers, the middle ages, enterprise. monasteries. breakthrough invention cast, movable type. a metal rod, to duplicate engraved. foundation Copper, intellectual, lead. political, manufacture religious sufficient wealthy merchant. molten lead monastic school traditional pilgrims. wine press. shrine papal decrees relics. a mammoth venture a lucrative business the Latin bible a flourishing trade first edition woodcuts aesthetically pleasing saints sold out time consuming contemporaries mirror-image identical. carved revolutionary technology a boost classical authors. manuscript production. intellectually elite scribes affordable great demand literate, founded,