Dissolution of the Monasteries (word)

advertisement

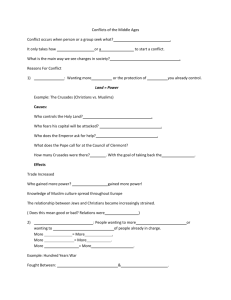

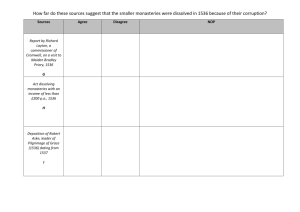

Dissolution of the Monasteries Background In 1529 there were more than 850 monasteries – closed and open The wealth of the monasteries was enormous and they held about 1/3 of the countries land. Money was acquired from rents of land they owned and profits from the Parish. This wealth was acquired over several centuries and a lot of wealth was from the wills of nobles who had made donations in order to lessen their time in purgatory. Most monasteries had been in existence for several centuries and were an integral part of the community. They were seen as a normal part of life. The popular opinion in the first half of Henry’s reign was that Monasteries would always continue to exist. 1520s Wolsey’s dissolutions Wolsey dissolved 29 small monasteries – all 29 houses were ‘decayed’ i.e. they were no longer seen as viable by their founders because of the limited numbers of monks or nuns who lived there. These monasteries and their wealth and land were used to build a grammar school at Ipswich and a new college at Oxford University (Cardinal College – later renamed Christ Church). THESE 29 CLOSURES WERE CARRIED OUT LEGALLY AND WITH PAPAL PERMISSION. Visitations and the Valor Ecclesiasticus 1535 Cromwell at this point was the King’s vice-regent and was responsible for the day-to-day control of the church. Visitations were seen as normal and a means of ensuring that Monasteries were conducting their affairs properly. These visitations in early 1535 were not completed and were interrupted by the Valor Ecclesiasticus. The VE was nothing less than an attempt to make a record of all the property owned by the Church in England and Wales. The work was carried out by unpaid commissioners (mainly local gentry) After the VE followed a series of visitations carried out by Cromwell’s employees Thomas Legh and Richard Layton. They were seen as unscrupulous, bullies whose aim was to uncover the bad points about the monasteries. Dissolution of the Lesser Monasteries 1536 March 1536 – an Act was passed stating that all monasteries with an annual income of less than £200 should be dissolved and their property pass to the crown (just under 300 monasteries fell into this category). Heads of these monasteries would be granted a pension and other members would have the option of transferring to a larger monastery or else ‘ceasing to be religious’ and go out into the world. The monasteries were then quickly stripped of their land and wealthy goods by commissioners. Sometimes the monasteries were stripped of all their wealth before the commissioners had arrived. Destruction of the remaining monasteries 1538-40 All the houses that had been pressurised into getting involved with the Pilgrimage of Grace were now on Henry’s vengeance list. The head of each of these houses was declared a traitor under an act of attainder passed by parliament. The possessions of these houses were passed to the king. There still existed some very wealthy monasteries after this but by 1540 they had all gone. The process of closing these monasteries was the same as in 1536 but the difference was that there was no similar act passed as the one in 1536. Why were the monasteries dissolved? Catholic interpretation Catholics argued that the dissolution had nothing to do with religion. They argue that a greedy king was persuaded by his unscrupulous minister (Cromwell) to steal all the monasteries wealth. They also argue that the monasteries were popular with the lay people and well respected. Protestant interpretation The Protestants argue that by the 1530s the monasteries were generally corrupt. They also despised the monastic connection to Catholic Doctrine and argued that the monasteries served no purpose now that the reformation had occurred and that the dissolution was an integral part of the reformation process. Therefore the Protestant argument supports the view that the monasteries were dissolved for religious reasons. Modern interpretation This view argues that the dissolution occurred because of Royal greed and were not religious – this is in line with the ‘top down’ view put forward by Elton and Scarisbrick. Evidence suggests that Henry believed quite strongly in the traditional values of the monasteries and this can be seen by the fact that he re-founded two monasteries so that they may pray for him, his wife and his ancestors. The bottom-up historians agree with this view in that there was very little opposition to the continued existence of the monasteries and that public opinion was just on the supportive side of neutral. They also argue that the corruption within the monasteries was no way near as bad as put forward by the Protestants. Conclusion – there was no popular demand for the destruction of the monasteries. The monasteries were not in a terminal state of collapse through moral corruption and the monasteries posed no religious or political threat to Henry. HOWEVER – the monasteries did possess vast amounts of wealth. The effects of the dissolution - Cultural vandalism? Remember some monasteries did survive and many monasteries that were dissolved were of very little architectural worth. Social/humanitarian damage – only 1500 out of 8000 monks and friars were unable to find other employment in the Catholic Church. Nuns did less well. THEREFORE little damage. Land rents set by the monasteries were similar in price to the new land owners who acquired their land once the monasteries had been dissolved. Most of the wealth and land acquired by Henry as a result of the dissolution was not squandered by Henry but sold off to the nobles at full price. Most of the money made through the sales of land was spent on wars against France and Scotland fought in the last years of Henry’s reign. When Henry died he left about half of the additional wealth that he had acquired.