Eliminate Discarded Pharmaceuticals in Drinking Water

advertisement

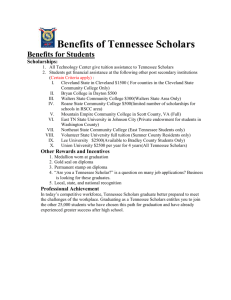

Eliminate Discarded Pharmaceuticals in Drinking Water: The Public Health Awareness Campaign. By Don Mitchell April 1, 2013 University of Memphis 1 Eliminate Discarded Pharmaceuticals in Drinking Water: The Public Health Awareness Campaign. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The quality of drinking water is diminishing. The unsafe practice of disposing unwanted pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) into the sewer system is one of the leading causes of tainted water quality. Waste water treatment plant effluents allow PPCPs into ground waters that eventually sieves into drinking water aquifers. The lack of better filtration technology and stricter detection limits compounds the waste water effluent problem. Literature reviews and data collected by Murray and colleagues, (2010) found that, “Trace pollutants referred to as, emerging contaminants (ECs) have recently been detected in the freshwater environment and may have adverse human health effects.” Most state Public Health Departments list primary prevention tenets according to Kovner and Knickman, (2011) as those of, “Helping people avoid the onset of a health condition and injuries” when it comes to protecting the public. This public health department policy is not confined to just the clinical definition but also The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services definition where “policies, programs, services, and research… conditions in which the population can be healthy” (p. 739). At the federal level, policies regarding research on PPCPs have been implemented but few policies on prevention or curbing the improper disposal of PPCPs at state levels have been realized. Policy guidelines appear to be mixed at best and state public health directors lack program initiatives regarding PPCP contamination. A cost effective means of delivering a public health message would be through a public service campaign. Its message is specifically designed to help eliminate PPCPs from being flushed Down the Drain and further burdening the waste water treatment facilities. Campaigns to increase public awareness about PPCP contamination would work very well with populations in urban, rural areas and will help kindle a dialog between state and federal stakeholders on permanent remediation efforts. The subsequent analysis will examine three policy alternatives: (1) the status quo policy, (2) other state policies, and (3) the Down the Drain policy. Policies are evaluated by: effectiveness, efficiency, equity 2 and political feasibility. This assessment determines that The Tennessee Public Health Director should adopt the “Down the Drain” public awareness campaign and closely work with the Governor for remediation of the PPCP problem. The Down the Drain public awareness campaign would be cost effective because it eliminates start-up costs by utilizing existing U.S. Environmental Protection Agency approved literature. Services can be equitably distributed throughout urban and rural populations whereby everyone receives intervention equally. Positive political feasibility would be met with enthusiasm because the health risk associated with PPCPs affects all stakeholders including residents, law makers and elected officials equally. “Organized community efforts aimed at the prevention of disease and promotion of health that focus on society” according to researchers Kovner and Knickman, (2011) defines—public health. The “Down the Drain” public health message will accomplish The State of Tennessee’s Public Health Department defined and stated goals of disease prevention and health promotion. INTRODUCTION Disposal of unused or unwanted pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCP) is an emerging and complex environmental issue for preserving citizen’s safety and the quality of drinking water. HISTORY The research of PPCPs has dated back to 1970s and has included health risks to humans, plant life and animals. Recent research by Koplin (2002) confirmed “contaminants being found in 80% of the streams sampled” (p. 1) and Seiler, Zaugg, Thomas and Howcroft (1999) indicated that “aspirin, nicotine and caffeine have long been found in sewage treatment facilities effluents”, (p. 405). Data from researcher, Barnes, et al. (2008) has shown the most frequently detected compounds in U.S. groundwater include “insect repellant, plasticizer, phosphate, fire retardant, veterinary and human antibiotics” (p. 193). McLachlan, Simpson and Martin (2006) studies “have shown that male fish in detergent-contaminated water express female characteristics, turtles are sex-reversed by polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), male 3 frogs exposed to a common herbicide form multiple ovaries” (p. 1). Testimony provided before U.S. Congress by Soloman (2010) indicated that the “source of hormonal contaminants in water is steroids used in livestock operations which contribute to widespread environmental contamination” (p. 8). Subtle consequences on marine life are bothersome as well, Daughton and Ternes, (1999) issued the following warning, “effects on aquatic organisms is particularly worrisome because effects could accumulate so slowly that major change goes undetected until the cumulative level of these effects finally cascades to irreversible change” (p. 907). Middleton and Ambrose (2008) research indicated, “Migratory waterfowl are increasingly becoming immune to antibiotics from tainted surface waters” (p. 338). Farm workers and U.S. food supplies are also potentially affected by PPCPs as shown by Graham, et at. (2009) report, "The carriage of antibiotic resistant enteric bacteria by flies in the poultry production environment increases the potential for human exposure to drug resistant bacteria. Management implications include the need to work toward removing more of these compounds during wastewater treatment processes, possibly by increasing solids retention times or implementing reverse osmosis” (p. 2701). Other studies of wastewater treatment plants have shown that “phthalates, estrogens and steroids may pass through treatment facilities without degrading” (Drewes & Hemming 2008) & (Alatriste-Mondragon 2003). The Tennessee Division of Water Resources report in 2012 has indicated, “The most common mechanism for their [PPCPs] entry into the environment is through wastewater discharges” (TN Division of Water Resources, 2012). Waste water treatment by itself is not enough for safe discharges with the subsequent discharging of PPCPs into U.S. waterways. Wastewater treatment plants and septic systems are generally not designed to treat discarded pharmaceutical waste, new nano-products or micro pollutants because of the extra fine particulate matter. This PPCP water contamination phenomenon is a worldwide event which affects drinking water globally and poses a health hazard for our citizens and the state. THE CURRENT STATUS QUO FOR REMEDIATION National Level of Preparedness 4 The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has known of the PPCP problem since the 80s and has authorized further analysis. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has also recognized the problem but has inadvertently sent mixed messages on the solutions; one of which was disposal of pharmaceuticals by flushing. State of Tennessee Preparedness In 2012, the State of Tennessee recognized the potential hazards to drinking water caused by PPCPs. There are no permanent policies locally or statewide for the recognition or remediation of PPCPs. The State of Tennessee has ordered testing on effluent discharges of waste water treatment plants at various locations which will be conducted by the University of Tennessee and federal grant money. The report is expected to be released by June 2013. In absence of any concrete findings by University of Tennessee and with the plethora of existing reports and data suggesting the dangers associated with PPCP contaminations, it seems reasonable to make assumptions that the Tennessee water quality is also diminishing. Organizational Issues The Tennessee Department of Public Health must be willing to take the lead on problem solving with the absence of any federal policy because of the expressed concern for its Tennessee citizens. With the absence of any meaningful state policy an awareness campaign can start with public utilities mailing brochures to citizens notifying them of the associated dangers of flushing PPCPs into the sewer system. Coordinating all stakeholders for state wide coverage of campaign mailers is crucial. Program implementation must be statewide, with local jurisdictions and private business as partners. Most cities and counties have either public or private water distributors as well as solid waste disposal infrastructure in place. Mailers will accompany billing statements. Sparsely populated rural areas may require additional mailers because they do not use public or private services. The U.S. EPA has a website: http://www.epa.gov/ppcp/ dedicated for informational means on best practices. 5 POLICY GOALS The policy goal of “least cost” method of efficiency of state resources. Policy goal should be one of social justice in equitable distribution and meet basic needs. Policy goal should be a better health outcome for all state populations. Policy goal should meet with political feasibility. Alternate Policy (PPCP Public Awareness Campaign) Mailers should use the EPA’s designed awareness policy. See appendices 1. Participation by all utility companies offering water services, sewage treatment or solid waste pick up should be mandatory. In rural areas where residents use “self-sufficient” services; those residents can be notified by county tax records. COMPARISON OF THE ALTERNATIVES DISCUSSION Currently, there are no listed permanent policies for the State of Tennessee in correctly disposing of unwanted pharmaceuticals and personal care products. The following dialog compares the status quo policy (or no policy) with a proposed public awareness campaign known as Down the Drain. Down the Drain public awareness will be effective, efficient, equitably distributed and generate better health outcomes with the state wide populations as well as stimulate positive political feasibility for the program. The objective of PPCP remediation will be to create a proactive program approach versus a reactive approach. The short term objective is to have a permanent program in place rather than a planned one day National event for collections. The short term program of Down the Drain would lead to a permanent policy and a longer term approach of strengthening waste water treatment plants ability to detect and eliminate PPCPs at nano levels. GOALS Effectiveness is to maximize population health from PPCP tainted drink water. Efficiency is a mix of public programs that maximize health outcomes at the least cost. Equity will be equal for all state residents because the current system has left the entire population exposed to the growing dangers of PPCPs and the potential threat of drinking contaminated water. Improved Public Health in state 6 populations would exist under the Down the Drain campaign. The current status quo policy is not acceptable in terms of better health outcomes in populations which mandated under the Tennessee Public Health Departments creed. Political Feasibility would materialize under the Down the Drain public awareness campaign because of its low cost and politically attractive nature and a need for state law for remediation and subsequent strengthening of waste water treatment plants. See Table 1. EVALUATION AND RECOMMENDATION It is recommended that the State of Tennessee proceed with the Down the Drain PPCP remediation program. The Tennessee Department of Public Health will be held responsible for its content and direction. Public Service announcements will be instituted statewide at minimal cost through TV / Radio and media website public service messages. Mailers to citizens would be cost effective because larger metropolitan cities in Tennessee have public utilities and send out monthly billing statement. Many of the state utility companies are profitable and are one of the few generating revenue on a permanent basis. These companies can afford to endure the cost of Down the Drain campaign without any specific state funding. Those cities would include a “message statement” within their customer’s utility bill. Rural areas have private water wells that have been drilled by private well drillers; those businesses would be made responsible for mailers and incur the cost to be considered as the cost of doing business. Most state residents would be informed and all state residents’ public health would be better served with higher quality drinking water. 7 Table 1. Alternative policy Recommendation Effectiveness Efficiency Equity Political Feasibility * a few states have an ad hoc PPCP policy in this region; Arkansas & Georgia have ad hoc and not very informative (no state policy); Kentucky, Alabama and Mississippi have no policy. 1 Current TN status quo policy no policy no policy no policy no policy 2 3 Other state policies* Down the Drain' policy yes* yes* yes* yes yes yes yes* yes Definitions: Population perspective Effectiveness: extent to which healthcare improves the health of patients and populations Efficiency: evaluates these improvements in relationship to the resources required to produce them Equity: health disparities and the fairness and effectiveness of the procedures for addressing them. Political Feasibility: policies favored by constituents Table by Don Mitchell, Definitions provided by: Aday, Lu Ann, et al. Evaluating the healthcare system: effectiveness, efficiency, and equity. Chicago: Health Administration Press, 2004. 8 Appendix 1 US EPA Website Poster 9 References Aday, Lu Ann, et al. Evaluating the healthcare system: Effectiveness, efficiency, and equity. Chicago: Health Administration Press, 2004. Alatriste-Mondragon, F., Gavala, H., Iranpour, R., Stenstrom, M. K., & Ahring, B. K. (2001). Biodegradation and Toxicity of Phthalate Esters during the Anaerobic Digestion of Wastewater Sludge. Proceedings of the Water Environment Federation, 2001(13), 902920. Barnes, K. K., Kolpin, D. W., Furlong, E. T., Zaugg, S. D., Meyer, M. T., & Barber, L. B. (2008). A national reconnaissance of pharmaceuticals and other organic wastewater contaminants in the United States--I) groundwater. Science of the Total Environment, 402(2), 192-200. Daughton, C. G., & Ternes, T. A. (1999). Pharmaceuticals and personal care products in the environment: agents of subtle change?. Environmental Health Perspectives, 107(Suppl 6), 907. Drewes, J. E., Hemming, J., Ladenburger, S. J., Schauer, J., & Sonzogni, W. (2005). An assessment of endocrine disrupting activity changes during wastewater treatment through the use of bioassays and chemical measurements. Water Environment Research, 12-23. Graham, J. P., Price, L. B., Evans, S. L., Graczyk, T. K., & Silbergeld, E. K. (2009). Antibiotic resistant enterococci and staphylococci isolated from flies collected near confined poultry feeding operations. Science of the Total Environment, 407(8), 2701-2710. Honoré, P. A., Wright, D., Berwick, D. M., Clancy, C. M., Lee, P., Nowinski, J., & Koh, H. K. (2011). Creating a framework for getting quality into the public health system. Health Affairs, 30(4), 737-745. Kovner, A. R., & Knickman, J. R. (2011). The current US health care system. Jonas and Kovner's Health Care Delivery in the United States, New York: Springer Publishing. Kolpin, D. W., Furlong, E. T., Meyer, M. T., Thurman, E. M., Zaugg, S. D., Barber, L. B., & Buxton, H. T. (2002). Pharmaceuticals, hormones, and other organic wastewater contaminants in US streams, 1999-2000: A national reconnaissance. Environmental science & technology, 36(6), 1202-1211. McLachlan, J. A., Simpson, E., & Martin, M. (2006). Endocrine disrupters and female reproductive health. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 20(1), 63-75. Middleton, J. H., & Ambrose, A. (2005). Enumeration and antibiotic resistance patterns of fecal indicator organisms isolated from migratory Canada geese (Branta canadensis). Journal of wildlife diseases, 41(2), 334-341. 10 Murray, K. E., Thomas, S. M., & Bodour, A. A. (2010). Prioritizing research for trace pollutants and emerging contaminants in the freshwater environment. Environmental pollution, 158(12), 3462-3471. Abstract retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20828905 Planning and Standards Section, Division of Water Resources, Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation (TDEC).2012 305(b) Report; Status of Water Quality in Tennessee. Retrieved from http://www.tn.gov/environment/wpc/publications/docs/2012_305b.pdf Seiler, R. L., Zaugg, S. D., Thomas, J. M., & Howcroft, D. L. (1999). Caffeine and pharmaceuticals as indicators of waste water contamination in wells. Ground Water, 37(3), 405-410. Soloman, G. M. (2010, February). Endocrine disrupting chemicals in drinking water: risks to human health and the environment. In Testimony on Behalf of the Natural Resources Defense Council before the US Congress, Committee on Energy and Commerce, Subcommittee on Energy and the Environment. Retreived from http://www.nrdc.org/health/files/hea_10022501a.pdf U.S. EPA resource page. EPA website. Retrieved from http://www.epa.gov/ppcp/ USGS resource page. USGS web site. Pharmaceuticals, Hormones, and Other Organic Wastewater Contaminants in U.S. Streams. USGS Fact Sheet FS-027-02. June 2002. Retrieved from http://toxics.usgs.gov/pubs/FS-027-02/ 11