View/Open

advertisement

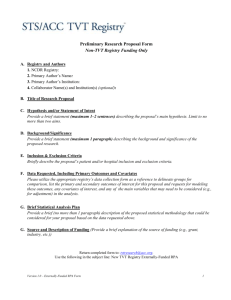

Belgian Eisenmenger registry The Belgian Eisenmenger registry: Implications for treatment strategies? Alexander Van De Bruaene MD, Marion Delcroix, MD, PhD°, Agnes Pasquet, MD, PhD*, Julie De Backer MD, PhD**, Michel De Pauw, MD**, Robert Naeije MD, PhD***, Jean-Luc Vachiéry***, Bernard Paelinck, MD, PhD$, Marielle Morissens, MD$$, Werner Budts MD, PhD. Division of Cardiology and Pneumology°, University Hospitals Leuven, *University Hospitals St Luc Brussels, **Ghent University Hospital, ***Erasme University Hospital Brussels, $University Hospital Antwerp, Belgium, and $$CHU Brugman Brussels. Address for correspondence: Werner Budts, MD, PhD Congenital and Structural Cardiology University Hospitals Leuven Herestraat 49 B-3000 Leuven Tel: 00-32-16-344369 Fax: 00-32-16-344240 E-mail: werner.budts@uz.kuleuven.ac.be 1 Belgian Eisenmenger registry Abstract Objective: Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) associated with congenital heart disease (CHD) usually results from a systemic-to-pulmonary shunt. Eisenmenger syndrome (ES) is characterised by severe irreversible PAH and reversal of a previous systemic-to-pulmonary shunt. A national registry of ES patients was initiated to optimise patient care and to provide epidemiological information regarding PAH and CHD in Belgium. Methods: All ES patients, older than 18 years, were selected through the local databases of ten centres in Belgium. After written informed consent, demographic, clinical, biochemical, technical, and treatment data were entered into the web based registry. Results: Ninety-one patients were included in the registry. Mean age was 3611 years (range 18-59 years). Complete atrioventricular septal defect (N=26, 28.6%), followed by ventricular septal defect (N=25, 27.5%) were the commonest defects. Forty-five percent were patients with Down syndrome. Down patients were younger (329 versus 4012 years; P=0.039), had worse functional capacity (Class II/III ratio: 15/16 versus 21/8; P=0.035) and received significantly less specific PAH treatment (7% versus 38%; P=0.002). Conclusion: Through the national Eisenmenger registry, 91 adult patients with ES were identified (estimated prevalence 11 per million inhabitants). Almost half of them were Down patients. Although having worse functional capacity, significantly less Down patients were receiving specific PAH treatment. Keywords Congenital heart disease, down syndrome, epidemiology, eisenmenger syndrome, pulmonary hypertension, registry. 2 Belgian Eisenmenger registry Introduction Adult patients with CHD represent a relatively new and continuously growing population. Currently, up to 90% of patients with congenital heart defects reach adulthood thanks to advances in medical, interventional and surgical procedures. PAH, defined as a mean pulmonary arterial pressure of > 25mmHg at rest or > 30 mmHg on exercise, develops in about 10% of patients with congenital shunts, whereas some of them evolve to the extreme end of the spectrum, the ES. [1,2] In Belgium, a few tertiary care centres developed advanced adult CHD clinics over the last years and the number of patients treated in each centre is continuously growing. Additionally, a number of “stable” patients are followed in secondary care centres. So far, there is no structured database of patients with CHD in Belgium and hence, it is currently difficult to identify and track adults with CHD in Belgium. Several reports stressed the importance of the implementation of national registries to provide epidemiological information on CHD and PAH and to optimise patient care by developing an efficient organisational structure, evidence based treatment protocols, and by assessing research and new treatment modalities.[3,4] Examples of recently developed databases are the CONCOR (‘CONgenital CORvitia’) project, a national registry and DNA-bank of patients with CHD in the Netherlands[5] and the EUROHEART survey on adult CHD, a retrospective, multi-centre study describing a European cohort of adults with CHD.[6] Two recently published PAH registries underline the need for further epidemiological research regarding PAH associated with CHD, because of a probable underestimation of the prevalence of PAH associated with CHD.[7,8] To obtain more structured national data and to create a forum for inter-academic and interdisciplinary cooperation regarding adult CHD and PAH in Belgium, a national registry of 3 Belgian Eisenmenger registry Eisenmenger patients was initiated. Here, we want to report the baseline characteristics of the patients included in this registry and draw the first conclusions. 4 Belgian Eisenmenger registry Methods Patient selection All patients with Eisenmenger physiology, older than 18 years, and living in Belgium, were eligible candidates for inclusion in the national registry. Eisenmenger physiology was defined as an intracardiac systemic-to-pulmonary communication with a reversal of the left-to-right shunt, resulting from severe pulmonary hypertension. Patients either had cyanosis at rest or during exercise. The Ethics Committees of the participating centres agreed with the registry, but before inclusion in the database, each patient, or his/her tutor, had to sign an informed consent. We aimed to include all adult patients with ES. Except age, no exclusion criteria were present. Participants and organisation The Eisenmenger registry was initiated in 2005 by the Belgian task force for pulmonary hypertension in collaboration with ten university and/or academic hospitals (Appendix). Belgium is a small country where the health care system allows easy access to tertiary care centres so that we might assume that nearly all patients with CHD and ES in Belgium were included. The task force was responsible for the creation, implementation, and management of the Eisenmenger registry. The registry was developed and is currently maintained by an independent data manager (Alabus Ag, Switzerland). The validity of a similarly designed data base was already proven in Switzerland and Austria. The input of data is web-based, so that each participating centre could log into the registry through internet with a personalized password. Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd (Allschwil, Switzerland) provided financial support to cover the costs of the development and the maintenance of the database, but had no access to the data entered. 5 Belgian Eisenmenger registry Data collection After signing the informed consent, data could be registered under a unique code for each patient. Physicians were only able to look at data from patients who were entered by themselves. Demographic data, medical history (Down syndrome or not, surgical procedures, and non cardiac history), clinical baseline characteristics (functional status), technical investigations (ECG, RX thorax,…), biochemical data, and treatment were collected. After registration, follow-up data could be entered. Statistical analysis All continuous variables were tested for normality. If present, mean ± standard deviation (SD) were used. Proportions were described with numbers (n) and percentages (%). For differences between continuous variables with normal distribution, an unpaired t-test was performed. Proportions were compared with the Chi square test. All tests were two-sided and P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Tests were performed with SPSS for Windows (version 15.0). Prevalence of ES was calculated as the ratio of all patients included in the registry and the total (adult) population (Belgium 2008: ~8.4 million). 6 Belgian Eisenmenger registry Results Patient characteristics Most patients with the ES were identified through the databases of the participating centres. More than 90% of them (or their tutor) agreed with inclusion in the registry and signed informed consent. A total of 91 patients were included, 69% (N=63) were female. Mean age was 3611 years (range 18-59 years). The main underlying diagnosis was complete atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD) (N=26, 28.6%) followed by ventricular septal defect (VSD) (N=25, 27.5%), complex defects (N=22, 24.2%), atrial septal defect (ASD) (N=10, 11%), and persistent arterial duct (PDA) (N=8, 8.8%). Forty-five percent (N=41) of the patients had Down syndrome. The functional class of the patients at inclusion is illustrated in Table 1. Reported symptoms were infrequent: palpitations (1%), vertigo (1%), syncope (4%), headache (8%), limb oedema (4%), chest pain (4%), haemoptysis (14%), epistaxis (1%). Clinical parameters are provided in table 2 and relevant biochemical characteristics are summarized in Table 3. Twenty-three percent of the patients were treated with specific PAH therapy (Table 4). Prevalence of ES in Belgium The overall population prevalence in the adult population of Belgium (~8.4 million) of ES was 11 per million population. Down versus non-Down patients Down patients were younger than non-Down patients (329 versus 4012 years; P = 0.039). As expected, Down patients were smaller than non-Down patients (15110 cm vs. 1648 cm; P < 0.001), but had a similar weight (6112 kg vs. 6111 kg; P = 0.796), resulting in a higher 7 Belgian Eisenmenger registry BMI in the Down syndrome group (265.4 kg/m² vs. 224.1 kg/m²; P = 0.005). An overview of these comparisons and other clinical parameters is listed in Table 2. VSD (N=14, 28 %) and complex defects (N=19, 38%) were the most common defects in the non-Down syndrome group, whereas in Down patients the AVSD was most prevalent (N=26, 63.4%). Although patients with Down syndrome had worse functional capacity when compared to the non-Down patients (Class II/III ratio: 15/16 versus 21/8; P = 0.035), only three Down patients (7%) received specific PAH treatment, which was significantly lower than the non-Down patients (38%) (P = 0.002) (Table 4). Finally, differences in biochemical parameters between both groups are listed in Table 3. 8 Belgian Eisenmenger registry Discussion Ninety-one patients with the typical ES were identified through the national Eisenmenger registry in Belgium, a prevalence of 11 per million adults older than 18 years. Almost half of them had Down syndrome. Most non-Down patients were receiving specific PAH treatment according to their functional class, whereas most Down-patients in class III did not. ES is defined as severe PAH associated with a large and non-restrictive intra- or extracardiac shunt, which leads to flow reversal through the shunt and central cyanosis.[2,9] As stated in the updated Venice classification[10], there are differences in pathological and pathophysiological aspects among patients with PAH associated with CHD, which are important for diagnosis, treatment and prognosis.[11] Some congenital heart defects with functional systemic-to-pulmonary shunts, such as an unrestricted AVSD, VSD, or a large PDA, invariably lead to pulmonary vascular remodelling and the clinical syndrome of PAH. By contrast, pre-tricuspid systemic-to-pulmonary shunts, as in the ASD, will only evolve to PAH in 10-20% of the cases.[9,12] Indeed, in general, it has been estimated that about 10% of patients with congenital shunts might develop PAH, whereas some of them evolve to the extreme end of the PAH spectrum, the ES.[1,2] Fortunately, due to better diagnostic tools and earlier defect repair, the evolution to ES in CHD has declined from ± 8% in the 1950’s to about 1-2% today.[1,2,13] However, epidemiological data regarding PAH associated with CHD remains scarce, often sub-represented in PAH registries, emphasising the need for further epidemiological research. Of the 1877 patients included in the Euro Heart Survey on adult CHD, which reflects a more selected population of patients treated at referral centres, 531 patients suffered from PAH (28,3%) and 231 patients (12,3%) had the typical ES.[14] In the Dutch CONCOR database, of the 5970 patients registered, 248 (4.2%) patients were characterized by PAH and 65 (1.0%) had evolved to the typical ES.[1] Using Dutch demographic data (2007), an estimated 9 Belgian Eisenmenger registry prevalence of 5.24 adult patients with ES per million is acquired. In PAH registries, the relative proportion of patients with PAH and CHD is also quite variable. The French Network on PAH (674 patients included in 2002-2003) and the Scottish Pulmonary Vascular Unit (374 patients hospitalised between 1986-2001) reported a proportion of 11% (N=76) and 23-27% (N=88), respectively.[7,8] Taken together, these results suggest a prevalence of patients with PAH associated with CHD in Western countries between 1.6 and 12.5 cases per million adults, with 25-50% having ES.[11] Most registries have the limitation of an important selection bias. Nevertheless, we suggest that the number of 91 patients is rather representative to estimate the prevalence of adult patients with ES in Belgium (11 per million inhabitants), which is twice the prevalence suggested by the CONCOR database. Despite comparable morbidity, survival prospects for Eisenmenger patients are far superior compared with idiopathic PAH.[15] It has been suggested that the presence of a ‘fetal’ phenotype of the right ventricle and/or the presence of a shunt, allowing right-to-left shunting when pulmonary pressure increases, are responsible for the prolonged survival in ES patients. [16,17] Interestingly, progressive histological changes have initially and exclusively been described in patients with PAH associated with CHD[18], which makes this subcategory of PAH patients particularly interesting. As these histological pulmonary vascular changes are similar to other forms of PAH, disease-targeting therapy which addresses the prostacyclin axis (prostanoids), NO/cGMP axis (phosphodiesterase (PDE) inhibitors) or endothelin axis (endothelin receptor antagonists (ERA)), has also been tried as treatment for patients with ES with similar results.[19] The placebo-controlled BREATHE-5 trial showed in ES with WHO class III that a dual-ERA (bosentan) significantly improved pulmonary hemodynamics and exercise capacity.[20] Improvement of functional class, exercise tolerance, and pulmonary hemodynamics, was also found in several uncontrolled studies treating patients with PDE 10 Belgian Eisenmenger registry inhibitors (sildenafil) or prostacyclin analogues. [10,21] According to the current guidelines, most of our registered patients were receiving specific PAH treatment, except the Down patients. Indeed, an important proportion of patients included in the registry (45%) had Down syndrome. This number is higher than reported by others.[15,22,23] This might be explained by three reasons. First, congenital heart defects are more prevalent in patients with Down syndrome, which has been estimated between 30% and 50%.[24] Among these, AVSD was the most common defect (35 – 60%), followed by VSD (15 -35%).[24] Both defects, when not repaired, might lead early to the development of PAH. Second, Down patients seem to be more prone to develop PAH, showing a more severe form of pulmonary vascular disease at an earlier stage of life.[25,26] And finally, earlier there has been some controversy regarding the surgical policy of congenital heart defects in Down patients, where some authors questioned the advisability of repairing complete AVSD in patients with DS, on the assumption that early surgery carries a high risk for an uncertain prospect.[27] This conservative approach resulted in several un-repaired defects, which could evolve to PAH. However, since several authors suggested that the presence of Down syndrome would be no risk factor for surgical shunt repair[28,29], more Down patients’ congenital heart defects have been corrected. This will probably lead to a decrease in prevalence of ES in the near future. Nevertheless, co-morbidity remains not uncommon, so that accurate risk assessment before surgical interventions is always necessary. We also found that a significantly smaller proportion of Down patients received specific PAH treatment, although they were younger, had lower functional capacity, higher hematocrit levels and a more impaired renal function, all of which are determinants of poorer outcome.[15,22,23] There are several reasons why Down patients received less specific PAH treatment. First, there is the issue of evidence based medicine. Until today, no randomized 11 Belgian Eisenmenger registry controlled trials have been performed to evaluate the benefit of specific PAH treatment in Down patients. Recent studies, including the BREATHE-5, applied rather strict inclusion criteria for their study populations, frequently excluding patients with Down syndrome or with complex congenital heart defects.[20] However, a recent study reported that bosentan administration was safe and well tolerated and led in the first months of treatment to a similar improvement in exercise tolerance as observed in non-Down patients.[30] Anyhow, bosentan has recently been approved by the EMEA (European Medicines Agency) for treatment of ES (including patients with Down syndrome) and it is expected that more Down patients with ES will receive specific PAH treatment in the future. Second, in Belgium a right heart catheterization is required for the reimbursement of chronic treatment with PAH medication. For most Down patients, this requires general anaesthesia. Although feasible, this implies additional risk and a lot of patients drop out at this point. The registry and the data obtained from the registry have some shortcomings. First, for inclusion in the Eisenmenger registry an informed consent was required. Although more than 90% of patients (or their tutor) agreed to participate in the study, a selection bias of the patients might be present. The contribution of the different centres to the registry might differ, adding to this selection bias. Second, not all centres used the follow-up protocol as predefined in the registry, so that some data could be missing. Data such as 6 minute walk test, echocardiography, neurohormones and hemodynamic data haven’t been included in the registry yet. However, by proposing a general protocol, participating centres will start to use it, which will allow to have a more complete data set for future outcome analysis. Third, reasons for the higher percentage of Down patients with ES and the lower percentage of patients treated with specific PAH treatment given in the text are speculative as the registry provides no information on the reasons why patients have or haven’t been operated on or been treated with specific PAH treatment. 12 Belgian Eisenmenger registry Conclusion In conclusion, through the national Eisenmenger registry, a substantial number of patients with ES were identified, which allows a realistic prevalence estimate of 11 adult patients with ES per million in Belgium, which is higher than reported in other registries. Although most patients were receiving specific PAH treatment according to their functional class, most Down patients were not. Whether or not to treat Down patients with specific PAH treatment remains an important dilemma in the current clinical management. 13 Belgian Eisenmenger registry Acknowledgements We want to thank Actelion Benelux, who gave the investigators the logistical support to start with a national registry of Eisenmenger patients. Actelion Benelux also supported financially the development and maintenance of registry, which was done by Alabus Ag (Switzerland). We want to thank Leuven Coordinating Centre to help us with data input. Conflicts of interest None declared. 14 Belgian Eisenmenger registry Appendix : Participating centres and investigators Prof. Dr. Werner Budts UZ Leuven, Prof. Dr. Marion Delcroix UZ Leuven, Prof. Dr. Agnes Pasquet Clin. Univ. Saint Luc, Prof. Dr Joelle Kefer Clin. Univ. Saint Luc, Dr. Julie De Backer UZ Gent, Prof. Dr. Daniel De Wolf UZ Gent, Dr. Michel De Pauw UZ Gent, Prof. Dr. Robert Naeijé Hopital Erasme, Prof. Dr. P Evrard, Clin. Univ. Mnt Godinne, Dr. Mark Meysman UZ Jette, Dr. Marielle Morissens CHU Brugman, Prof. Dr. Luc Pierard CHU Sart Tilman, Dr. Marco Naldi CHU Sart Tilman, Dr. Thierry Weber Hopital de la Citadelle, Prof. Dr. L. Delaunois Clin. Univ. Mnt Godinne, Dr. Hans Slabbynck AZ Middelheim, Dr. Dirk Van Ranst UZ Antwerpen, Prof Dr. Bernard Paelinck UZ Antwerpen, Prof. Dr. Walter Van Mieghem ZOL. 15 Belgian Eisenmenger registry References 1 Duffels MGJ EP, Berger RMF, van Loon RLE, Hoendermis E, Vriend JWJ, van der Velde ET, Bresser P, Mulder BJM.: Pulmonary arterial hypertension in congenital heart disease: An epidemiologic perspective from a dutch registry. Int J of Card 2007;120:198-204. 2 Bouzas B GM: Pulmonary arterial hypertension in adults with congenital heart disease. Rev Esp Cardiol 2005;58:465-469. 3 Report of the British Cardiac Society Working Party: Grown-up congenital heart (guch) disease: Current needs and provision of service for adolescents and adults with congenital heart disease in the uk. Heart 2002;88:i1-i14. 4 Engelfriet P TJ, Kaemmerer H, Gatzoulis MA, Boersma E, Oechslin E, Thaulow E, Popelova J, Moons P, Meijboom F, Daliento L, Hirsch R, Laforest V, Thilen U, Mulder B.: Adherence to clinical guidelines in the clinical care for adults with congenital heart disease: The euro heart survey on adult congenital heart disease. Eur Heart J 2006;27:737-745. 5 Vander Velde ET VJ, Mannens MMAM, Uiterwaal CSPM, Brand R, Mulder BJM.: Concor, an initiative towards a national registry and DNA-bank of patients with congenital heart disease in the netherlands: Rationale, design, and first results. Eur J of Epid 2005;20:549-557. 6 Engelfriet P BE, Oechslin E, Tijssen J, Gatzoulis MA, Thilen U, Kaemmerer H, Moons P, Meijboom F, Popelova J, Laforest V, Hirsch R, Daliento L, Thaulow E, Mulder B.: The spectrum of adult congenital heart disease in europe: Morbidity and mortality in a 5 year follow-up period. The euro heart survey on adult congenital heart disease. Eur Heart J 2005;26:2325-2333. 16 Belgian Eisenmenger registry 7 Humbert M SO, Chaouat A, Bertocchi M, Habib G, Gressin V, Yaici A, Weitzenblum E, Cordier JF, Chabot F, Dromer C, Pison C, Reynaud-Gaubert M, Haloun A, Laurent M, Hachulla E, Simonneau G: Pulmonary aerterial hypertension in france: Results from a national registry. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;173:1023-1030. 8 Peacock AJ MN, McMurray JJV, Caballero L, Stewart S: An epidemiological study of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Resp J 2007;30:104-109. 9 Diller GP GM: Pulmonary vascular disease in adults with congenital heart disease. Circulation 2007;115:1039-1050. 10 Galie N TA, Barst R, Dartevelle P, Haworth S, Higenbottam T, Olschewski H, Peacock A, Pietra G, Rubin LJ, Simonneau G: Guidelines on diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. The task force on diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension of the european society of cardiology. Eur Heart J 2004;25:2243-2278. 11 Galie N MA, Palazzini M, Negro L, Marinelli A, Gambetti S, Mariucci E, Donti A, Branzi A, Picchio FM: Management of pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital systemic-to-pulmonary shunts and eisenmenger's syndrome. Drugs 2008;68:1049-1066. 12 Chan SY LJ: Pathogenic mechanisms for pulmonary arterial hypertension. J of Molec and Cell Card 2008;44:14-30. 13 Oechslin EN HD, Connelly MS, Webb GD, Siu SC: Mode of death in adults with congenital heart disease. Am J Cardiol 2000;86:1111-1116. 14 Engelfriet P DM, Möller T, Boersma E, Tijssen JGP, Thaulow E, Gatzoulis MA, Mulder BJM: Pulmonary arterial hypertension in adults born with a heart septal defect: The euro heart survey on adult congenital heart disease. Heart 2007;93:682-687. 17 Belgian Eisenmenger registry 15 Daliento L SJ, Presbitero P, Menti L, Brach-Prevert S, Rizzoli G, Stone S: Eisenmenger syndrome. Factors relating to deterioration and death. Eur Heart J 1998;19:1845-1855. 16 Chin KM KN, Rubin LJ: The right ventricle in pulmonary hypertension. Coron Artery Dis 2005;16:13-18. 17 Hopkins WE WA: Severe pulmonary hypertension without right ventricular failure: The unique hearts of patients with eisenmenger syndrome. Am J Cardiol 2002;89:3438. 18 Heath D EJ: The pathology of hypertensive pulmonary vascular disease. A description of six grades af structural changes in the pulmonary arteries with special reference to congenital heart disease. Circulation 1958;18:533-547. 19 Rubin LJ BD, Barst RJ, Galie N, Black CM, Keogh A, Pulido T, Frost A, Roux S, Leconte I, Landzberg M, Simonneau G.: Bosentan therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med 2002;346:896-903. 20 Galie N BM, Gatzoulis MA, Granton J, Berger RM, Lauer A, Chiossi E, Landzberg M, Bosentan Randomized Trial of Endothlin Antagonist Therapy-5 (BREATHE5) Investigators.: Bosentan therapy in patients with eisenmenger syndrome: A multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Circulation 2006;114:48-54. 21 Chau EM, Fan KY, Chow WH: Effects of chronic sildenafil in patients with eisenmenger syndrome versus idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Int J Cardiol 2007;120:301-305. 22 Diller GP DK, Broberg CS, Kaya MG, Naghotra US, Uebing A, Harries C, Goktekin O, Gibbs JS, Gatzoulis MA.: Presentation, survival prospects, and predictors of death in eisenmenger syndrome: A combined retrospective and case-controle study. Eur Heart J 2006;27:1737-1742. 18 Belgian Eisenmenger registry 23 Cantor WJ HD, Moussadji JS, Connelly MS, Webb GD, Liu P, McLaughlin PR, Siu SC: Determinants of survival and length of survival in adults with eisenmenger syndrome. Am J Cardiol 1999;84:677-681. 24 Freeman SB TL, Dooley KJ, Allran K, Sherman SL, Hassold TJ, Khourthy M, Saker DM.: Population-based study of congenital heart defects in down syndrome. Am J of Med Genet 1998;80:213_217. 25 Yamaki S YH, Kado H, Yonenaga K, Nakamura Y, Kikuchi T, Ajiki H, Tsunemoto M, Mohri H: Pulmonary vascular disease and operative indications in complete atrioventricular canal defect in early infancy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1993;106:398-405. 26 Clapp S PB, Farooki ZQ, Jackson WL, Karpawich PP, Hakimi M, Arciniegas E, Green EW, Pinsky WW: Down's syndrome, complete atrioventricular canal and pulmonary vascular obstructive disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1990;100:115-121. 27 Bull C RM, Shinebourne EA: Should management of complete atrioventricular canal defect be influenced by coexistent down syndrome? Lancet 1985;1:117-149. 28 Al-Hay AA MS, Yacoub M, Yacoub M, Shore DF, Shinebourne EA.: Complete atrioventricular septal defect, down syndrome, and surgical outcome: Risk factors. Ann Thorac Surg 2003;75:412-421. 29 Lange R GT, Busch R, Hess J, Schreiber C.: The presence of down syndrome is not a risk factor in complete atrioventricular septal defect repair. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2007;134:304-310. 30 Duffels MGJ VJ, van Loon RLE, Berger RM, Hoendermis ES, van Dijk AP, Bouma BJ, Mulder BJ.: Down patients with eisenmenger syndrome: Is bosentan treatment an option? Int J of Card 2008. 19 Belgian Eisenmenger registry Tables Table 1: Functional classes of the Eisenmenger patients at inclusion. (percentage of patients) Global Population Down syndrome Non-Down syndrome NYHA I 10% 0% 10% NYHA II 44% 21% 23% NYHA III 41% 30% 11% NYHA IV 4% 0% 4% 20 Belgian Eisenmenger registry Table 2. Demographic and clinical characteristics P-value Global Down Non-Down Down vs Population syndrome syndrome non-Down Female/male (n) 63/28 24/17 39/17 0.045 Age (y) 36±11 32±9 40±12 0.039 Length (cm) 158±11 151±10 164±8 < 0.001 Weight (kg) 60±11 61±12 61±11 0.796 BMI 24±5 26±5 22±4 0.005 Systolic BP (mmHg) 118±20 108±11 125±22 < 0.001 Diastolic BP (mmHg) 72±12 65±7 78±12 < 0.001 Heart rate (beats/min) 77±16 72±11 83±19 0.037 Oxygen saturation (%) 84±8 84±6 84±9 0.937 21 Belgian Eisenmenger registry Table 3. Biochemical characteristics P-value Global Down Non-Down Down vs Population syndrome syndrome non-Down Haematocrit (%) 56.9±9.4 60.4±5.7 51.4±11.6 < 0.001 Hemoglobin (g/dl) 19.0±3.4 20.1±1.9 17.3±3.9 0.001 MCV (fl) 94.9±6.7 95.9±8.1 91.0±11.6 0.060 Creatinine (g/dl) 1.1±0.4 1.2±0,4 1.1±0.5 0.523 Uric acid (mg/dl) 6.9±2.4 7.4±2.5 6.0±2.0 0.029 Iron (mg/dl) 113.3±67.6 115.0±62.2 105.4±64.1 0.701 TSH (mIU/l) 4.5±3.9 6.2±5.2 3.2±1.8 0.054 22 Belgian Eisenmenger registry Table 4. Type of specific treatment of patients with Eisenmenger syndrome P-value Specific Global Down Non-Down Down vs non- Population syndrome syndrome Down 22 (23%)* 3 (7%) 19 (38%) 69 (77%) 38 (93%) 31 (62%) treatment No specific treatment * specific treatment: alpha-blocking agent (1%), bosentan (10%), sitaxsentan (8%), sildenafil (2%), remodulin (1%), sildenafil + bosentan (1%) 23