Dr. Peale`s Essay On Ethics

advertisement

Dr. Peale’s Essay On Ethics

From: Philosophy 307- Contemporary Moral Issues and Ethical Perspectives

Longwood University

I.

I.

Ethics, A summary Outline

A. A. A Definition Of Ethics

B. B. Philosophical Starting Point

C. C. The Standards Of Morality And Ethics

i.

i. Moral Standards

ii.

ii. Ethical Standards

II.

II.

The Theories Of Ethics

A. A. Consequentialists Theories

i.

i. Theories Of Ends Or

Consequences Good In Themselves

ii.

ii. The Theories

1. 1. Ethical Egoism (EE) And Psychological Egoism

(PE)

2. 2. Utilitarianism

B. B. Theories, Non-Consequentialist And Teleological

i.

i. Plato’s Ethics

ii.

ii. Aristotle’s Ethics

iii.

iii. Christian Ethics

C. C. Non-Consequentialist Theories (Deontological)

i.

i. Act Deontological Theories

ii.

ii. Rule Deontological Theories

(Kant)

D. Virtue Ethics

I.

I.

ETHICS, A SUMMARY OUTLINE

A. A DEFINITION OF ETHICS

NORMATIVE ETHICS is that branch of Philosophy which Provides

standards, theories or principles to guide the behavior or action of persons

towards doing what people ought to do or what it is right to do. It helps us

decide in any given specific situation, what is the right or wrong thing to or

what we ought or ought not to do.

B. PHILOSOPHICAL STARTING POINT

In my definition of normative ethics, I stated that philosophy provides

standards or theories or principles to guide our behavior. Below I will spell out just what I mean

by such standards or principles.

First I want to ask why do we need moral standards or ethical rules, principles or theories

anyway?

Some people may believe that moral or ethical judgments are merely matters of opinion,

such as personal feelings or tastes. Other people may believe that such judgments have a

certainty or are self-evidently true.

There are arguments to show that both these beliefs are wrong to which I will some

come.

Since mere opinion won’t do, or since there aren’t any self-evidently true moral

judgments, what is needed is some middle ground. This is provided by identifying the bases or

standards on which to ground moral judgments. What we need in ethics is the point of view that,

on a certain basis (es), it may be argued that someone is doing what they should (or should not

do) or ought (or ought not) to do. We will consider the bases or standards below in Section II. C.

Take the people who believe that moral judgments are merely a matter of opinion. Some

of these people may be called “subjectivists,” by which view Rachels means the view “that our

moral opinions, are based on our feelings, and nothing more. On this view [he writes] there is no

such thing as ‘objective’ right or wrong.” (Rachels, EMP, p.31)

An example: I suffer from insomnia. I feel that killing octogenarians for sport in the

middle of the night during the time that I cannot sleep is fun and ok, so for me that behavior is

right, for my judgment that it is morally permissible is based on my feelings and nothing more.

That is my personal opinion.

This view reduces moral judgments to matters of personal private feelings and matters of

taste.

Consider the following arguments against subjectivism:

1. If subjectivism were true, then there would be no such phenomena as

(1) (1) genuine moral or ethical agreement or

disagreement;

(2) (2) moral or ethical progress or retrogression;

(3) (3) moral or ethical exemplars;

(4) (4) most tellingly, no standards to distinguish

between right and wrong;

2. But there are examples of (1)-(4);

3. Therefore, Subjectivism, as defined, is not true and is not a satisfactory

theory of morality or ethics.

People may believe that moral judgments have a certainty or are self-evidently true.

Against this point of view is the claim that for any moral or ethical judgment, based on

any rule, principle or theory of ethics or any moral custom in culture, there are justifiable

exceptions.

I want to argue that in any moral problem there is a dilemma. A moral dilemma, by

definition, is a dilemmic situation in which there is more than one way to go towards resolving it,

and this means that any one duty to go any one way is not self-evident or certain.

This point can be pinned down more firmly by taking on Kant, and this isn’t done until

Section II. C. 2 {ii}.

On the basis of these arguments we may conclude that it is not the case either that moral

or ethical judgments are merely matters of opinion or taste, based on feeling and nothing more,

nor is it the case that moral or ethical judgments have a certainty or are absolute or self-evident.

Therefore, we must take a middle position and have a system of bases or standards for

grounding moral or ethical judgments.

C.

THE STANDARDS OF MORALITY AND ETHICS

These bases are found in the standard, acceptable customary patterns of behavior in one’s

culture or sub-culture, or they are found in the rules, principles and theories of ethics. Moral

philosophy, in the main is concerned with arguments between the standards on which moral

judgments are based.

1.

1.

Moral Standards

“Morality” or morals come from the term “mores,” which means customs in a culture. So

“morality” and “morals” are cultural terms.

One of the standards in the field, therefore are the customary acceptable standards in a

culture or sub-culture. We may define being moral or practicing morality as follows: To be moral

or to practice morality is to act in accordance with customary acceptable standards in a culture or

sub-culture. To act immorally is to act in a way contrary to such customary acceptable standards.

Morality is a social institution “something that is coordinate with but different from art,

science, law, convention or religion, though it may be related to them.” (Frankena, Ethics, p.6)

Morality is social in its origin. “It is an instrument of society as a whole for the guidance

and regulation of groups.” (Frankena, Ethics, p. )

2.

2.

Ethical Standards

We need another normative discipline with standards other than moral standards to guide

our behavior, and this for the reason that we all know that we often do what is customary and

acceptable in a culture but which we know to be wrong. Besides, we often need to criticize and

alter moral standards towards what we consider the betterment of persons and social institutions.

In other words to do what is moral is not necessarily to do what is right.

As an example to pin the point down, consider the case of the Montgomery Alabama bus

boycott of 1955-1956. Prior to the boycott it was moral, based on the acceptable customs in that

culture at that place and time, that blacks should sit in the back of the bus. The black community,

in effect argued that such moral standards violated an ethical principle, the principle of

(egalitarian) justice, according to which every person as a person is equal and should be treated

as such. Or simply, treat equal people equally. With regard to bus riding behavior blacks and

whites should be treated equally, for the color of one’s skin is ethically irrelevant, but was

morally relevant, to where a person should sit on a bus.

So we may define being ethical as follows: To be ethical is to act according to principles,

which are freely and rationally constructed by the agent, and which are not necessarily taken

from the culture.

I want to argue that these principles come from the human mind, which freely and

rationally thinks them up to guide human behavior towards what is right, especially where the

rightness of the action is contrary to prevailing moral customs.

This is a convenient point to introduce cultural relativism, for a person taking this point

of view may well raise objections to this line of thought.

Cultural Relativism affirms the following six propositions:

“1.

Different societies have different moral codes.

2.

There is no objective standard that can be used to judge one societal code

better than another.

3.

The moral code of our own society has no special status; it is merely one

among many.

4.

There is no ‘universal truth’ in ethics- that is, there are no moral truths that hold

for all peoples at all times.

5.

The moral code of a society determines what is right within that society; that is, if

the moral code of a society says that a certain action is right, then that action is

right, at least within that society.

6.

It is mere arrogance for us to try to judge the conduct of other peoples. We should

adopt an attitude of tolerance towards the practices of other cultures.”

(Rachels, EMP, p. 18)

The cultural relativist, so defined, subscribes to “the cultural differences argument,”

which goes as follows:

“(1) Different cultures have different moral codes.

(2) Therefore, there is no objective ‘truth’ in morality. Right and wrong are only

matters of opinion, and opinions vary from culture to culture.”

(Rachels, EMP, p.19)

Rachels thinks that the trouble with the cultural differences argument “is that the

conclusion does not really follow from the premise- that is, even if the premise is true, the

conclusion might still be false. The premise concerns what people believe: in some societies,

people believe one thing; in other societies, people believe differently. The conclusion, however,

concerns what really is the case. The trouble is that this sort of conclusion does not follow

logically from this sort of premise.” (Rachels, EMP, p.19)

Consider the case of the Chinese on the issue of infanticide. There are long-standing

cultural traditions in China that families prefer boy babies to girl babies. Males come ahead of

females in Confucian thought. Family lines are carried in the names of the boy babies not the

girls. There is a special relationship the man has with the land, e.g. in Wang Lung in Pearl

Buck’s The Good Earth. Also boys and men work better on the land than the girls do, and boys

are not as likely to marry and to go away from the family home. Presently it has been realized

that there simply are too many Chinese people, and everyone recognizes that. The government

has tried to deal with this situation by setting up the one child per family requirement, which is

enforced by stiff fines and other penalties.

Say you are like me in being enamored of the Chinese, of speaking the language and

valuing the culture. Say you are in China living with a Chinese family that you have come to

care for and who care for you. Say this family has just borne a girl baby, and one night you hear

them talking about drowning the infant the next night. Is there anything you can and ought to

say?

If you are a cultural relativist and are one in a strict sense there isn’t any judgment you

should make upon their behavior. But perhaps there is something you ought to say. Here is where

the distinction between morality and ethics comes to play.

You could say that you understand and value the cultural traditions of the Chinese as

explained, but you also value human life. You could produce a rational principle, the right to life,

that the life of the baby girl is valuable, and given normal development will actualize greater

value as she matures.

You could argue that infanticide is wrong because it violates a principle, the principle of

the right to life.

Another example: Why should a professor at Longwood not play favorites with his or her

students. Perhaps the professor could do a bit of research and determine that playing favorites

was customary and acceptable among Longwood faculty and therefore moral. But such behavior

could still be judged wrong on an ethical basis, for that would violate the principle of egalitarian

justice, that equal people (the students) should be treated equally.

II.

THE THEORIES OF ETHICS

So, the need of ethical rules, principles and theories which contain them, has been

established. The next task is to generate a system of such rules, principles and theories to

maximize useable standards for the making of ethical judgments.

A.

CONSEQUENTIALIST THEORIES

Perhaps the best most natural place to begin is with consequentialist theories. Here one

begins by appealing to the consequences of an action to determine whether that action is right or

ought to be done.

Now what is there in general in the consequences of any action, which could justifiably

stand to make that action right or obligatory? What ends or consequences are good in

themselves, and not just ends which are instrumental towards the furthering of other ends and so

on infinitum?

1.

THEMSELVES

THEORIES OF ENDS OR CONSEQUENCES GOOD IN

(1)

(1)

a.

b.

c.

d.

e.

f.

(2)

Happiness

a.

b.

c.

d.

e.

f.

balance of pleasure over pains

Aristotelian happiness

Epicurean happiness

Stoic Happiness

Christian happiness

Happiness as a psychological- spiritual state of well being.

The Good Will (Kant), Power (Machiavelli),

Knowledge (Plato)

Let us concentrate on happiness. Why happiness? As the argument goes, happiness is the

one good or end in itself that we human beings desire for its own sake. All other things we

desired are desired for the sake of happiness, e.g. the good will, power, knowledge, not to

mention health, enough money to be comfortable etc. Only happiness is desired for its own sake.

Next we have to have a definition of “happiness;” I opt for definition f; the merits and

demerits of the various kinds of happiness will be considered in the criticisms of the various

theories.

2.

ETHICAL THEORIES

(1)

Ethical Egoism (EE) and Psychological Egoism (PE)

“According to Ethical Egoism, thee is only one ultimate principle of conduct, the

principle of self-interest, and this principles sums up all of one’s natural duties and obligations.”

(Rachels, EMP, p.77) The one and only one basic obligation is to bring happiness to oneself.

This view is based on a psychological doctrine, on PE, which says that the one and only

one basic motivation or aim in behavior is to bring happiness to oneself.

Putting EE and PE together we may say that one ought to do what is in one’s own best

interest largely because one does do that anyway. Or we ought to do what we do anyway. This is

much more convenient than Christian ethics, for example, which argues that we ought to do what

we don’t do anyway!

One argument seems to point to a strength in EE:

“(1) We ought to do whatever will promote the best interest of

everyone alike.

(2)

(2)

The interests of everyone will best se promoted if each of us adopts

the policy of pursuing our own interests exclusively.

(3)

(3)

Therefore, each of us should adopt the policy of pursuing our own

interests exclusively.

Critique of EE and PE: EE would be undermined if PE were found to be false. One

argument to show that it is false is to describe believable cases where there are genuinely

altruistic motivations or aims, say the actions of one best friend or one true loved one to the

friend or beloved. Another argument against PE is to show, as Rachels tries to do, that “the

deepest error in psychological egoism, is that “once accepted, everything may be interpreted to

support it.” (Rachels, EMP, pp.72-73) In other words, the hypothesis is untestable and therefore,

irrefutable.

(2)

(2)

Utilitarianism (U)

If we’re not satisfied with Egoisms we could turn to Utilitarianism, the doctrine which

holds that one ought to do that which maximizes utility or ought to do the act which

promotes “ the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people” or simply produces

the greatest amount of happiness altogether.

Utilitarianism is that “theory proposed by David Hume (1711-1776) but given

definitive formulation by Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) and John Stuart Mill (18061873)…” (Rachels, EMT p. 90)

This theory subscribes to the Principle of Utility, which quoted from Bentham is

as follows:

“By the Principle of Utility is meant that principle which approves

or disapproves of every action whatsoever, according to the

tendency which it appears to have to augment or diminish the

happiness of the party whose interest is in question; or what is the

same thing in other words, to promote or to oppose that

happiness.” (Rachels, EMP, p.91; the quotation is from Bentham’s

The Principles of Morals and Legislation)

“Classical Utilitarianism- the theory defended by Bentham and Mill- can be

summarized in three propositions:

First, actions are to be judged right or wrong solely on the virtue of their

consequences. Nothing else matters. Right actions are, simply, those that have the best

consequences.

Second, in assessing consequences, the only thing that matters is the amount of

happiness or unhappiness that is caused. Everything else is irrelevant. Thus right actions

are those that produce the greatest balance of happiness over unhappiness.

Third, in calculating the happiness or unhappiness that will be caused, no one’s

happiness is to be counted as more important than anyone else’s. Each person’s welfare is

equally important. As Mill puts it in his Utilitarianism, the happiness which forms the

utilitarian standard of what is right in conduct, is not the agent’s own happiness, but that

of all concerned. As between his own happiness and that of others, utilitarianism requires

him to be as strictly impartial as a disinterested and benevolent spectator.” (Rachels,

EMP, pp. 102-103)

Try this for an analogy for the utilitarian moral agent: he or she is like an outboard

motor boat skimming rapidly across a calm lake. The boat is the moral agent; the wake is

the happiness created in the consequences of the behavior of the boat, and the boat is not

in the wake.

One merit of this view is that with people practicing utilitarianism more people

would be positively affected by the happiness wakes of more people, and thus the world

would be a happier place.

An interesting and controversial issue: Utilitarianism implies that we have a duty

to concern ourselves with the happiness of other people. Do we have such a duty?

Note that the utilitarian is taking issue with the second premise of the argument

presented for EE on page 7, that the interests of everyone will best be promoted if each of

us adopts the policy of pursuing our own interests exclusively.

The version of utilitarianism here considered is often referred to as Act

Utilitarianism (AU). According to this doctrine the moral agent considers each act

individually and calculates whether the performing of that act will promote the most

happiness.

Critique of Utilitarianism: There are a number of problems, in fact there are such

a large number and a wide variety of problems that one wonders if the theory can survive.

There are problems concerning the utilitarian calculation of the amount of

happiness produced in, say, course-of-action #1, vs. course-of-action #2.

What the utilitarian typically does is to add up the units of happiness produced by

#1 vs. #2 and then opts for the course of action which produces the greater number of

such units of happiness.

Often “units of happiness” are called “utils.” But how can happiness be quantified

into a number of utils. Well, this may depend on how “happiness” is defined. See the

options for such a definition given on p.6. It is difficult to see how option (f) can be

quantified in to utils; if a balance of pleasures over pains is what is meant by happiness,

then the quantification problem might be alleviated.

But consider further that types and instances of states of happiness often vary not

only in quantity but often in quality. Some states of happiness are qualitatively better and

more valuable than others. Take Mill’s famous example: “Socrates dissatisfied is better

than a pig satisfied.” Or the happiness that comes from doing calculus is greater than

from playing tic tac toe. The students like the following kind of examples: the happiness

that comes from getting an A on a test is qualitatively less than the happiness that comes

from graduating from High School.

Another problem concerning calculation: When we do an act, after calculating the

quantity of utils which will be produced, there is a time lag between the doing of the act

and the calculation. There is a time-lag between the two. So when we do an action,

according to this theory, we don’t know whether we’ve done right or wrong.

Rachels concentrates on the sorts of problems concerning the propositions that

happiness or the consequences are the only things that matter. Rights matter, and justice

and he talks about certain “backward looking reasons,” such as promise keeping. What

makes keeping a promise right is not that the keeping of it will produce the most happy

consequences for the greatest number of people. What makes a promise right is that one

made it.

A defense of utilitarianism against the Rachels sort of critiques can be found in

shifting from Act Utilitarianism to Rule Utilitarianism. Here one adopts the sorts of rules

that will answer the Rachels’s sorts of objections and argues that the following of these

rules will have the long run consequences of there being a greater balance of happiness

over unhappiness in the world.

B.

THEORIES NON-CONSEQUENTIALIST AND TELEOLOGICAL

There are certain types of theories which do not appeal to the consequences to justify an

action or a rule, but appeal, rather to the ends or purposes (telos) of an action.

1.

Plato’s Ethics

Virtue in the individual person and justice in the state is the

harmonious working together of the faculties of the soul

and the classes of the state under the dominance of reason

or the philosopher kings in the pursuit of knowledge of the

GOOD.

One ought to act with the purpose of achieving and maintaining such a well

tempered harmony in the individual soul or in the state.

2.

Aristotle’s Ethics

One ought to become morally virtuous (by developing

virtuous habits) and intellectually virtuous (by becoming

more contemplative) in order to achieve what is the final

end good in-itself for mankind-that is happiness, that is

direction of life by reason which, in all actions, determines

the mean between extremes.

3.

C.

Christian Ethics (CE)

One ought to do whatever God commands or do whatever

is loving for the purpose of being faithful to God’s

commands or for the purpose of manifesting God’s love in

the world.

NON-CONSEQUENTIALIST THEORIES (DEONTOLOGICAL) (NC-DT)

Deontological theories are theories of the ethics of duty, which duties we have

independent of any consideration of the consequences or the purposes of the action.

1. Act Deontological Theories

One ought to do whatever is just, fair or right which is known in

each specific act or situation.

These theories are often intuitionistic, as one has an intuition of what is just, fair and

right. Such intuitions are often compared with mathematical intuitions of, say, the axioms of

geometry.

Intuitions, as we all know, however can lead us astray, unless there is a check upon them,

and they are no longer intuitions.

2. Rule Deontological Theories, e.g. Kant

Kant is, perhaps, the most important ethical theorist in the Western tradition. Be that it

may, if there wasn’t a Kant we’d have to invent him, for someone had to take the position he

took, which is a clear logical alternative, and which is so much out of fashion today.

Kant’s ethic can be characterized by three marks in that it is

Universal, in that what is right or wrong for one person is right or wrong for any

other person at any time and any place;

Rational, in that when one acts truly morally one acts “absolutely independently

of inclination or desire,” and the test as to whether any behavior is right or wrong is a

purely rational test, having nothing to do with the consequences of the act;

Categorical, in that the imperatives of morality are without condition. The

opposite kind of moral imperative for Kant are hypothetical, that is based on certain

conditions desired, as in Utilitarianism.

The imperative of morality is categorical, which are binding on the rational mind.

One statement of his categorical imperative is as follows:

“Act only according to that maxim by which you can at the same time will that

should become a universal law.” (Rachels, EMP, p.119)

Rachels explains: “This principle summarizes a procedure for deciding whether

an act is morally permissible. When you are contemplating doing a particular action, you

are to ask what rule you would be following if you were to do that action. (This will be

the ‘maxim’ of the act.) Then you are to ask whether you would be willing for that rule to

be followed by everyone all the time. (That would make it a ‘universal law’ in the

relevant sense.) If so, the rule may be followed, and the act is permissible. However, if

you would not be willing for everyone to follow the rule, then you may not follow it, and

the act is morally impermissible.” (Rachels, EMP, p.119)

Take, for example a lying promise. A lying promise is a statement one makes, “I

promise that…,” in which one actually makes the promise by so saying; it also is a lie in

that at the time of promising one has no intention to do what one is promising. Say, for

example that you are in debt, and to put off your debtor you are making a lying promise.

The maxim of the act would be something like this: when you need to extricate yourself

from difficulty make a lying promise. Now can you will that this maxim would become a

universal law, that whenever one needs to extricate oneself from a difficulty, make a

lying promise. No, for then the whole institution of promise keeping would break down.

In other words the making of a lying promise is a practically contradictory act. To

generate other absolute duties (“Don’t tell lying promises”), all you need to do is to find

the practical contradiction to the very act itself.

So lying is wrong, for in lying one is making a statement of something that is the

case which is not the case. So suicide is wrong for one is committing suicide for one is

depressed, and the natural psychological function of depression is to impel one’s own

improvement of one’s own situation, so suicide contradicts the impulsion to improve.

Kant’s second version of his categorical imperative is this: “Act so that you treat

humanity, whether in your own person or in that of another, always as an end and never

as a means only.” (Rachels, EMP, p.128)

To treat oneself or others as an end is to treat them as if they are rational (able to

think and make decisions), free (not under the compulsion of any external agent or

agency) and autonomous (independent). This is to treat people, including oneself with

respect. To treat people, including oneself, as a means only is the contradiction of

treatment as an end. It doesn’t follow that we cannot treat people, including ourselves, as

means. As I tell my students, we are treating each other as means, but that is not

inconsistent with mutual treatment as ends.

From this principle we can generate further absolute duties (“no nos”) as follows:

One should never murder, rape or torture anyone, for these are clear cases of treatment as

means only, as are lying promises, lies and suicides.

So there we have the Kantian system of absolute duties, made absolute with no

thought or consideration of the ends or consequences of the action.

Critique of Kant: The flaw, which may be fatal, is the problem of a genuine

conflict of duties. A genuine conflict of duties is such that to do one duty is to violate

another. An example would be, as explained by Rachels in EMP, pp. 124-125, would be

this: you are a Dutch fisherman during the war, hiding Jews on your boat and the

powerful Nazi war vessel speeds up to you. Its captain asks whether you are hiding Jews

on board. If you say “yes” then you are party to murders, which is absolutely wrong; if

you say “no” then you are lying, which is absolutely wrong.

Kant’s own answer to this critique is this: He denies that there are any genuine

conflict of duties. There is always a way out. Kant denies the obvious; perhaps he is right.

Ross comes along later in Britain and tries to save Kant by making a distinction

(When you’re at an impasse, draw a distinction) between actual duties and primae facie

duties. The Dutch fisherman has a primae facie conflict of duties, but it is clear that only

one of these, lying to the Nazis, should become an actual duty.

Does the Ross move succeed? This depends on whether Ross or anyone else can

come up with a procedure for determining which of two conflicting primae facie duties is

more important to fulfill. Ross said it depends on our intuition, which leaves us where we

were with the act deontological theories above. In a more sanguine statement, Ross once

admitted that he didn’t know how to determine which of the conflicting primae facie

duties was most important.

At this point a suggestion may be made for a composite view: Be a Kantian,

fulfilling absolute duties until you come up against a genuine conflict of duties and then

become a utilitarian, making utilitarian calculations as to which course of action would

produce the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people. By this method many or

all of the problems besetting the naturally attractive utilitarian theory would be solved, as

would the (“fatal”?) flaw in Kant.

D.

VIRTUE ETHICS

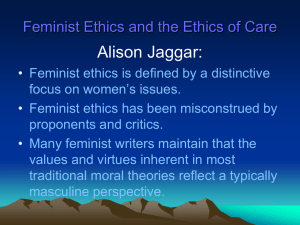

This is an interestingly different and recently a highly popular type of ethics

different in aim and perhaps in essence from the type of ethics we have been discussing.

We have been considering the ethics of action, aimed at determining what is right for a

person to do or what a person ought to do.

The ethics of virtue considers a different question: “What traits of character make

one a good person?

If we opt for an ethic of virtue, we are returning to ethics at the beginning of

Western civilization namely with Aristotle and Plato.

To develop an ethic of virtue, we need a definition of what a virtue is. Rachels

offers the following: “A virtue [is] a trait of character that is good for a person to have.”

(Rachels, EMP, p.163)

Next we need a list of virtues, and we need to analyze what the virtues consist in.

Take the virtue of courage and the Aristotelian program of analyzing this as a mean

between extremes. Courage is a mean between the extremes of cowardice as a defect and

foolhardiness as an excess. When we describe any situation in which a person mediates

between cowardice and foolhardiness and is actually courageous, then we will know what

that virtue consists in.

Next we need an explanation as to why the virtues are important to have. Rachels

offers two answers to this question: “Virtues are needed to conduct our lives well…[and]

they are qualities needed for successful human living.” (Rachels, EMP, pp.169-170)

Next we need an answer to the question as to whether the virtues are the same for

everyone. Here we can debate between virtue relativism and virtue universalism, and this

debate will be reminiscent of the debate between cultural relativism and its opponents as

noted above on page (omitted).

There are clear advantages to a virtue ethics. It provides moral motivation, the

doing of our duty not just out of duty but out of kindness, compassion etc. Secondly, it

rightly throws doubt on the standard view of impartiality built into the theories of ethics

of action. The virtuous person, practically speaking, is going to favor the interests of

some over the interests of others. Wouldn’t I be unvirtuous in some way if I cared as

much for my students as I do for my own children?

Finally we need to consider whether either the ethics of action or the ethics of

virtue are complete in themselves or whether each needs the other for the most developed

ethical theory. At this point we are at one of the cutting edges of the field.