Wake Forest-Manchester-Shaw-Aff-Districts

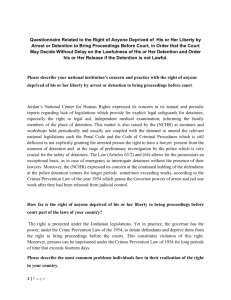

advertisement