Executive Summary

advertisement

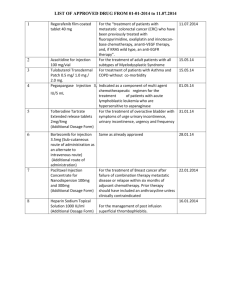

Suggested Revisions to the U.S. Enironmental Protection Agency’s Underground Injection Control (UIC) Program By: Michael Brittenburg Executive Summary In today’s world we are seeing the greatest production and consumption of natural gas the world has ever seen. Pennsylvania produces so much natural gas that we have even begun to export it to other countries. Although, natural gas extraction is still a fairly young technology and the regulations for which are still maturing. Pennsylvania has numerous regulations already in place to reduce environmental and water supply contamination as well as protect human and animal wildlife, both terrestrial and aquatic. However, more protection from the contaminant, fracking waste fluid, can only have positive consequences for the people of the Commonwealth and the rest of the American people. The following document examines current regulations involved in guiding the permitting process of Class II injection wells used to dispose of fracking waste fluids and states two suggested revisions to the UIC program; one revision that allows for communities to safeguard themselves in the case when an injection well site is proposed for an unsavory location, the other revision requires the EPA to conduct routine inspections of all injection wells nationwide. Michael Brittenburg Page 1 Background In the past fifteen years, unconventional gas wells using the method of hydraulic fracturing (fracking) have become more and more popular in Pennsylvania, Texas, and a number of other states as a method of extracting natural gas from the Marcellus and Utica shale bedrock layers beneath the Earth’s surface. As demonstrated by Figure 1, the reach of the many unconventional wells in Pennsylvania is extensive and each well requires “4 to 8 million gallons of water, typically within about 1 week,” to be injected into the ground for the use of opening coal seams (Abdalla, C. W. & Drohan, J. R., 2010). Of the 4 to 8 million gallons of water injected into the ground, on average about 10% comes back to the surface as wastewater contaminated with saline waters (brine) and the cocktail of many, mostly toxic, chemicals added to the water to make “fracking fluid” (Swistock, B. & Rizzo, D., 2014). The wastewater that returns to the surface is treated, reused, and/or disposed of. Figure 1. Map of unconventional wells drilled in Pennsylvania from 2007-2013. Source: Penn State Marcellus Center for Outreach & Research (MCOR) http://marcellus.psu.edu/resources/maps.php Michael Brittenburg Page 2 Due to the influx of new wells being drilled each year, the demand for useable water (regulated river basins, streams, lakes, etc.) is high in the hydraulic fracturing industry. “The Susquehanna River Basin Commission (SRBC) estimates preliminarily that, at full development, basinwide water withdrawals (an average of 28 million gallons per day) by all gas extraction operators drilling in the Marcellus shale will equal the amount of water withdrawn currently in three days for power production in the basin” (Abdalla et al., 2010). Although the water usage of the natural gas industry in the Susquehanna River Basin is very little in comparison to the power industry, the growing natural gas industry could possibly lead to “water-use conflicts” (Abdalla et al., 2010). In addition, the greater demand of water to be used in hydraulic fracturing corresponds to a larger volume of waste fluids that later will need to be disposed of. Legal Framework According to the EPA’s Underground Injection Control (UIC) program, applicants for a Class I, II, III, or V injection well permit must include, among other information, a “listing of all permits or construction approvals received or applied for” (1EPA, 40 C.F.R. § 144.31, 2014). This includes but is not limited to: Hazardous Waste Management program under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) UIC program under the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) National Pollution Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) under the Clean Water Act (CWA) Michael Brittenburg Page 3 Prevention of Significant Deterioration (PSD) program under the Clean Air Act (CAA) For newly proposed Class II well injection sites, permits likely necessary will be UIC and NDPES permits. RCRA permits are required for the disposal of hazardous waste, which does not encompass Class II injection wells as long as the applicant can acquire and comply with a UIC permit (1EPA, 40 C.F.R. § 270.60, 2014). A PSD permit will only be required if the site is located in an attainment region (2EPA, 2014). UIC permits may be terminated during their term or denied for renewal by the Director for one of the following reasons: 1. “Noncompliance by the permittee with any condition of the permit” (1EPA, 40 C.F.R. § 144.40, 2014). 2. The permittee witholds relevant facts in the application or during the permit issuance phase, or misrepresents relevant facts at any time (1EPA, 40 C.F.R. § 144.40, 2014). 3. “A determination that the permitted activity endangers human health or the environment and can only be regulated to acceptable levels by permit modification or termination” (1EPA, 40 C.F.R. § 144.40, 2014). Problem with Current Regulations The regulations of Class II injection wells does not allow for community opinion to overturn permit issuance without proof of a threat to environmental or public health. Injection Michael Brittenburg Page 4 well site permits are not reviewed thoroughly enough by the EPA for factual data and issued permit sites are not monitored enough for permit compliance. Discussion The most common public concern related to hydraulic fracturing is the health risks of contamination of ground- and surface waters due to direct contamination during drilling, disposal well injections, leaking waste fluid storage containers, and waste fluid spills due to transportation accidents. However, according to a study conducted by Pennsylvania State University, “statistical analyses of post-drilling versus pre-drilling water chemistry did not suggest major influences from gas well drilling or hydrofracturing (fracking) on nearby water wells, when considering changes in potential pollutants that are most prominent in drilling waste fluids” (Boyer, E. W., Swistock, B. R., Clark, J., Madden, M., & Rizzo, D., 2012). In fact, “only one drinking water well appeared to be affected by drilling as evidenced by subtle increases in many of its constituents after drilling and fracking, including bromide, chloride, sodium, barium, total dissolved solids, hardness, and more” (Boyer et al., 2012). Although contamination of ground- and surface waters rarely occurs during drilling, other mechanisms of contamination are still present, and the concern for potential harm of these mechanisms still exists and is growing as the public becomes more educated on the topic. According to a study conducted by William L. Ellsworth (2013), the disposal of these waste fluids by means of injection wells has increased seismic activity in areas near injection well sites in Ohio, a common importer of waste fluids for the natural gas industry. Ellsworth recommends that, although “the largest fracking-induced earthquakes have all been below the Michael Brittenburg Page 5 damage threshold of modern building codes,” if seismic activity increases, the use of injection wells should be suspended (Ellsworth, 2013). If injection wells were to be suspended, the fracking industry would have many more millions of gallons of waste fluids that would need to be disposed of in other locations or by other means that may be more expensive in monetary terms and both of which carry public and environmental concerns. Deep well injection of fracking waste fluids are of growing concern among Pennsylvanians particularly. If the seismic activity previously mentioned located in Ohio continues to increase, it is likely that the state will reduce, or less likely cease, its imports of waste fluids for well injection. This would put a greater burden on Pennsylvanian natural gas companies to find an alternative for disposing their own waste fluids. One alternative that is becoming more popular is deep well injection right here in Pennsylvania, which is receiving considerable opposition already. A number of deep injection wells have been allowed by the EPA to be drilled or converted from old fracking sites (Legere, L., 2014). One of these permitted injection wells located in Clearfield County was temporarily shut down in 2012 “after the company noticed the well was leaking brine and continued injecting fluids into it for months without notifying the EPA” (Legere, 2014). The company operating the injection well, Exco Resources, was fined “$159,624 for the violation, under the Safe Drinking Water Act” (Phillips, S., 2012). The owners and operator of the injection well site in Clearfield County exhibited blatant disregard for the health of the public and environment. Pennsylvanian citizens are rightfully concerned with the increase of injection wells within the state. Michael Brittenburg Page 6 Another injection well permit was issued in February, 2014 in Clearfield County for Windfall Oil & Gas of Falls Creek, PA (Legere, 2014). “[The] EPA said there are no drinking water wells and no documented abandoned oil and gas wells that penetrate the injection zone within a quarter mile of the Windfall well site” (Legere, 2014). Public opinion strongly disagreed with the proposed site because, in fact, there are 14 private water wells located within 1,000 feet of the site (Legere, 2014). “A well location map [was] submitted to the state,” but despite the community’s efforts the permit was still issued (Legere, 2014). These two cases exhibit the EPA’s incompetency and disregard of public and environmental health. “State Rep. Matt Gabler (R-Clearfield/Elk) called the EPA’s decision to issue the permit ‘reckless’ and ‘irresponsible’” (Legere, 2014). Representative Gabler sponsored House Bill No. 1566 during the 2013 session, which contained legislation that would prevent injection wells from being drilled within 1,000 feet “of a building, water well, surface water intake, reservoir or other water supply extraction point used by a water purveyor, in existence when a permit application to drill or operate the disposal well is submitted, without written consent of the owner of the building or water well or the water purveyor” (General Assembly of PA, 2013). Had the proposed bill become legislation before the permit issuance was decided, the permit would have been thrown out and the community would be better off. Michael Brittenburg Page 7 Solution I believe that in order to secure public health and happiness, communities should be allowed to veto an injection well permit via a two-thirds (2/3) vote. This condition could be added to 40 C.F.R. § 144.51, “conditions applicable to all permits.” I also have a solution to the EPA’s poor permit compliance monitoring. Routine inspections should be conducted at all injection well sites located in Pennsylvania once a month. The EPA currently relies on the permitted company to submit factual data of the processes and proceedings that occur at the injection well sites, and although the data may be accurate, no one will know for sure unless someone goes to the site and performs an inspection. Some sort of clause could be written into the same section of regulations, “conditions applicable to all permits,” or could be included in the “requirements for recording and reporting of monitoring results” section which would be applied to all injection wells in the nation (EPA, 40 C.F.R. § 144.51, 144.54). Michael Brittenburg Page 8 Works Cited Abdalla, C. W. & Drohan, J. R. (2010). Water Withdrawals for Development of Marcellus Shale Gas in Pennsylvania. Penn State Extension. Retrieved from http://pubs.cas.psu.edu/freepubs/pdfs/ua460.pdf Boyer, E. W., Swistock, B. R., Clark, J., Madden, M., & Rizzo, D. (2012, March). The Impact of Marcellus Gas Drilling on Rural Drinking Water Supplies. The Center for Rural Pennsylvania. Retrieved from http://www.rural.palegislature.us/documents/reports/Marcellus_and_drinking_water_ 2012.pdf Ellsworth, W. L. (2013, July 12). Injection-Induced Earthquakes. Science Magazine, 341(6142), 1225942-142. Retrieved from http://www.sciencemag.org/content/341/6142/1225942.full General Assembly of Pennsylvania. (2013). House Bill No. 1566. Retrieved from http://www.legis.state.pa.us/CFDOCS/Legis/PN/Public/btCheck.cfm?txtType=PDF&sess Yr=2013&sessInd=0&billBody=H&billTyp=B&billNbr=1566&pn=2115 Holahan, R. & Arnold, G. (2013, October). An institutional theory of hydraulic fracturing. Ecologic Economics, 94(10), 127-134. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921800913002206 Legere, L. (2014, February 17). EPA approves waste disposal well in Clearfield County. Stateimpact.npr.org. Retrieved from http://stateimpact.npr.org/pennsylvania/2014/02/17/epa-approves-waste-disposalwell-in-clearfield-county/ Merrill, T. W. (2013, June). Four Questions about Fracking: The Law and Policy of Hydraulic Fracturing: Addressing the Issues of the Natural Gas Boom. Case Western Reserve Law Review, 63(4), 971-993. Retrieved from http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?action=interpret&id=GALE%7CA334277565&v=2.1&u= carl39591&it=r&p=LT&sw=w&authCount=1 Phillips, S. (2012, April 12). EPA Fines Company for Deep Injection Well Failure. Stateimpact.npr.org. Retrieved from http://stateimpact.npr.org/pennsylvania/2012/04/12/epa-fines-company-for-deepinjection-well-failure/ Michael Brittenburg Page 9 Swistock, B. & Rizzo, D. (2014). Gas Well Drilling and Your Private Water Supply. Penn State Extension. Retrieved from http://extension.psu.edu/natural-resources/water/marcellusshale 1U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2014, October 29). 40 CFR Chapter I Parts 52, 122, 144, 270. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from http://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/textidx?SID=df1ff0d55b19713ee6f88a5434e87e9a&tpl=/ecfrbrowse/Title40/40chapterI.tpl 2U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2014, October 8). Prevention of Significant Deterioration (PSD) Basic Information. Retrieved from http://www.epa.gov/NSR/psd.html Michael Brittenburg Page 10