French Revolution: Thesis Statements & De-Christianization

advertisement

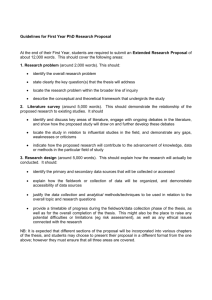

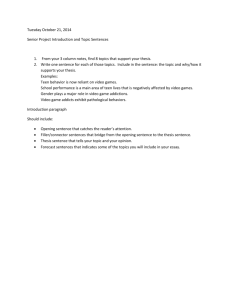

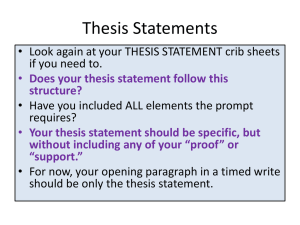

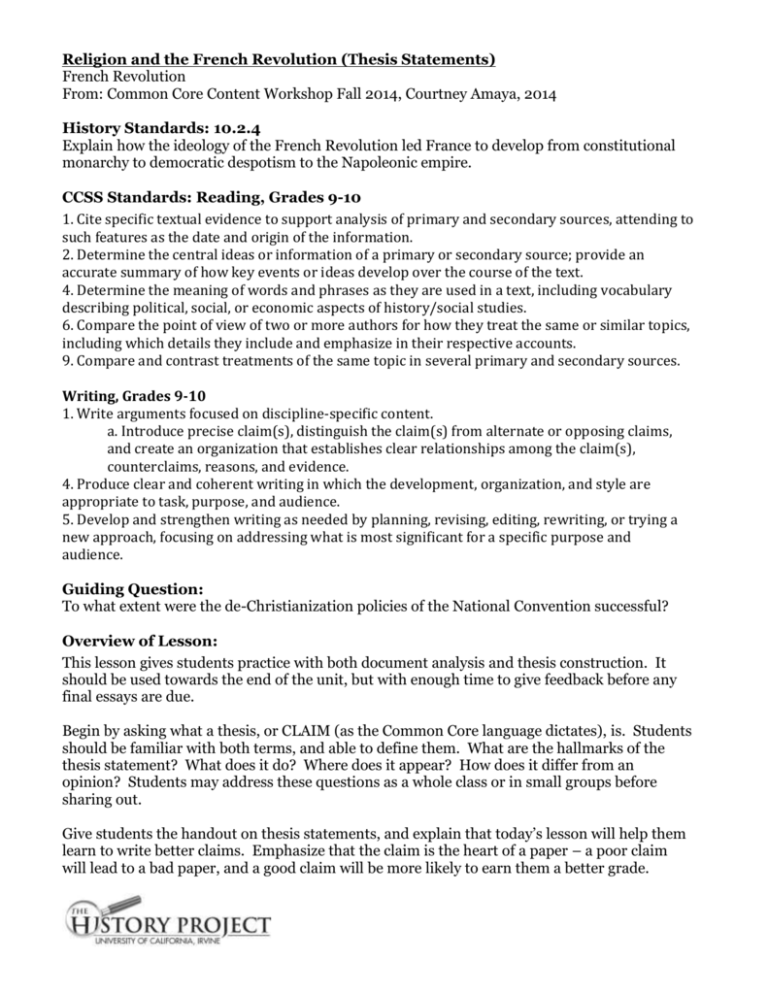

Religion and the French Revolution (Thesis Statements) French Revolution From: Common Core Content Workshop Fall 2014, Courtney Amaya, 2014 History Standards: 10.2.4 Explain how the ideology of the French Revolution led France to develop from constitutional monarchy to democratic despotism to the Napoleonic empire. CCSS Standards: Reading, Grades 9-10 1. Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources, attending to such features as the date and origin of the information. 2. Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of how key events or ideas develop over the course of the text. 4. Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including vocabulary describing political, social, or economic aspects of history/social studies. 6. Compare the point of view of two or more authors for how they treat the same or similar topics, including which details they include and emphasize in their respective accounts. 9. Compare and contrast treatments of the same topic in several primary and secondary sources. Writing, Grades 9-10 1. Write arguments focused on discipline-specific content. a. Introduce precise claim(s), distinguish the claim(s) from alternate or opposing claims, and create an organization that establishes clear relationships among the claim(s), counterclaims, reasons, and evidence. 4. Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience. 5. Develop and strengthen writing as needed by planning, revising, editing, rewriting, or trying a new approach, focusing on addressing what is most significant for a specific purpose and audience. Guiding Question: To what extent were the de-Christianization policies of the National Convention successful? Overview of Lesson: This lesson gives students practice with both document analysis and thesis construction. It should be used towards the end of the unit, but with enough time to give feedback before any final essays are due. Begin by asking what a thesis, or CLAIM (as the Common Core language dictates), is. Students should be familiar with both terms, and able to define them. What are the hallmarks of the thesis statement? What does it do? Where does it appear? How does it differ from an opinion? Students may address these questions as a whole class or in small groups before sharing out. Give students the handout on thesis statements, and explain that today’s lesson will help them learn to write better claims. Emphasize that the claim is the heart of a paper – a poor claim will lead to a bad paper, and a good claim will be more likely to earn them a better grade. Review the situation in which one is asked to write claim. Explain that one must consider more than simply the prompt or issue n front of them – good writers will account for evidence and context, and only write their thesis after reading and organizing their information. Then split the class in three and have each section read and quickly summarize one type of thesis statement. They should then present the information to the class in less than one minute (timed). Ask students what types of prompts they think would best match each type. Briefly review the reminders, and use the Eleanor Roosevelt thesis to model the difference between a good claim and a poor one. Ask students to spot the differences between the two. Once this is done, students will begin analyzing the sources as they would for a DBQ. For this exercise, they may work in partners or small groups if they are not yet ready to complete analysis individually. Remind them that they must complete the graphic organizer before beginning their claims, and that they should make notes on the sides of documents connecting them to the prompt. Once the planning worksheet is complete, allow total classroom silence for 10minutes while students craft their claims. Encourage them to craft more than one, and also to check their claim by re-reading the information to see if it will support the argument they advance. Practicing historical writing (Free Response Question) Steps to writing a successful essay: 1. Read the prompt CAREFULLY a. What is it asking you to do? b. Does it have more than one part? c. Is there a choice of responses? 2. Identify the HISTORICAL CONTEXT a. Identify Time and Place b. Years, era, decade c. location, region, urban, rural, foreign, domestic 3. Brainstorm a. Create a list of specific factual information b. Names, events, concepts relevant to the question 4. Categorize the data (3 themes/ideas/categories should always be used) a. Sort the pieces of information by their similarity to other pieces b. Name each category – to be used in the thesis when defining the themes of the essay c. Helpful acronyms (PERSIA, SPRITE) 5. Write a TOPIC SENTENCE for EACH category a. This will be your intro sentence for each of your body paragraphs 6. Write your THESIS a. Make sure it fully addresses the prompt b. Can be more than one sentence Types of Thesis Statements 1. The Funnel: set the stage, define terms, thesis (answer the prompt using categories) Example: Was Robespierre a bloodthirsty charlatan or defender of the Republic? During the 1790s, Robespierre and the Mountain created the Committee of Public Safety. It intended to lead the sans-culottes and use the constitution for the benefit of the French people. Robespierre truly believed he was defending the Republic, but his actions make it clear that he was really just a bloodthirsty charlatan. Robespierre brought disaster and terror to France through his policies of de-Christianization, arresting people without proper evidence and trial, and sending thousands of innocent people to be executed by guillotine. 2. XYZ: Set the stage first, then answer the question, and to finish, follow it up with your Plan of Attack (POA). The POA should contain your organizational categories. Example: Analyze the causes of the French Revolution of 1789. The French Revolution of the late 18th century broke out because of the political, economic, and social problems in France which had existed since the time of Louis XIV. The 3rd estate lacked voting and political power, the tax structure was unfair to the lower classes, and the 3rd estate still owed feudal dues and obligations to the nobility, contradicting the Enlightenment idea that all men are created equal. 3. “Although”: Using ‘although’ to show an understanding of the nuances of historical analysis. Example: Was Robespierre a bloodthirsty charlatan or defender of the Republic? During the time of the Reign of Terror in France, Robespierre, although somewhat successful in his plight for power and total control of the Republic, was a prime example of incompetence as a ruler. Aside from reigning terror over his people, he not only threatened violence, but he put it into action. Robespierre was an unfair and blood thirsty ruler because he inflicted tyranny, provoked fear amongst the people, and turned the country into an absolutist state. Reminders: Never use the first person in your thesis - “I would argue that…” is a waste of my time! Technically, a thesis can appear anywhere in an essay – BUT – I want your thesis to be strongly stated in your intro paragraph. o Whether it is the first or last sentence of the intro paragraph is up to you. o It can be more than one sentence Each body paragraph then offers evidence to support the thesis The conclusion should re-state the thesis and hopefully adds something to it so it isn’t merely repetitious. More examples: "Eleanor Roosevelt was a strong leader as First Lady." This thesis is unspecific and lacks an argument. Why was Eleanor Roosevelt a strong leader? "Eleanor Roosevelt recreated the role of the First Lady by her active political leadership in the Democratic Party, by lobbying for national legislation, and by fostering women’s leadership in the Democratic Party." This thesis has an argument: Eleanor Roosevelt "recreated" the position of First Lady, and a three-part structure (organizational categories) with which to demonstrate just how she remade the job. ************************************************************************* The French Republic Historical Context: Once in power, the National Convention began a policy of de-Christianization. On November 24, 1793, the National Convention adopted a revolutionary calendar to replace the Gregorian calendar (established by the Roman Catholic Church in 1582). New Year’s Day was moved from January 1 to September 22, the founding date of the French Republic, and this date in 1792 marked the beginning of Year One. The months were renamed, assigned a uniform 30 days and divided into 3 weeks of 10 days each (décade). The remaining 5 days of the year were to be celebrated as republican festivals (sans-culottides) in honor of Virtue, Intelligence, Labor, Opinion, and Rewards. The revolutionary calendar continued through the republican era but was eventually abolished by Napoleon I in 1806. Prompt: To what extent were the de-Christianization policies of the National Convention successful? Source #1: Gilbert Romme, head of the calendar reform committee, “Report on the Republican Era,” speech before the National Convention, September 20, 1793. The Church calendar was born among an ignorant people. For eighteen centuries it has served to mark the progress of fanaticism, the debasement of nations, the persecution and disgust experienced by virtue, talent, and philosophy under cruel despots. We are finished with royalty, the source of all our ills. Source #2: *Note: The Gregorian calendar system returned in 1806. Source #3: French official. Taken from Spielvogel textbook, Western Civilization, 4th edition. The new calendar faced intense popular opposition, and the revolutionary government relied primarily on coercion to win its acceptance. Journalists were commanded to use republican dates in their newspaper articles. But many people refused to give up the old calendar, as one official reported: “Sundays and Catholic holidays, even if there are ten in a row, have for some time been celebrated with as much pomp and splendor as before. The same cannot be said of decadi, which is observed by only a small handful of citizens.” Source #4: Source #5: “Instruction Concerning the Era of the Republic and the Division of the Year,” decree of the National Convention, October 5, 1793. Soon commerce and the trades will be summoned to new progress through uniformity of weights and measures, which will eliminate incoherence and inexactitude. The arts and history also require a new measurement of time, freed from all errors that credulity and superstitious routine have handed down to us from centuries of ignorance. It is this new standard that the National Convention today presents to the French people; at the same time, by its exactness, simplicity, and detachment from every opinion not sanctioned by reason and philosophy, it shows the character of our revolution. Source #6: François-Sebastien Letourneux, Minister of Interior, circular to all départements and municipalities, November 9, 1797. After having been the calendar of all Frenchmen for several years, the republican calendar is at present only that of the public officials. The enemies of the Republic attack it furiously. They say that the interval between days of rest is too long, that the artisan and farmer cannot work nine days in a row. This objection must be welcomed by the lazy. Industrious and active citizens are grateful to their legislators for having reduced the number of days spent in rest. Our enemies also say, either in bad faith or great ignorance, that the new division of time is contrary to that of nature. Yet the new calendar was the work of our most skilled astronomers, and was conceived only to correct the vices and errors of the old. Source #7: Government official in the French town of Steenwerck, Picardy, letter to superiors, March 3, 1798. The short time the people spend in the republican temple [a former church] celebrating Tenth Day and revolutionary festivals is an affront to republicans. Entirely decorated with all the old signs of fanaticism, the building displays no symbol of liberty, equality, or the republic. No matter where one looks, one sees only images, crucifixes, confessionals, and chapels —all as under the monarchical regime. Source #8: "View of the Mound of Champ de la Reunion on the Festival That Was Celebrated in Honor of the Supreme Being" In this watercolor of the Festival of the Supreme Being, we see a procession that includes a woman wearing a Phrygian cap paraded past a statue of Hercules holding two smaller statues of Liberty and Equality, towards a Liberty tree, atop the hill. In the foreground, a patriotic woman explains the meaning of the spectacle to her young son, an allegory of the instructive intent of the entire festival. Source #9: Pierre-Joseph Denis, a former Girondin imprisoned during the Terror and then recalled to the National Convention, Opinion on the Decades, 1795. The Jacobins were able to overthrow the religion of our fathers and trample underfoot the venerated objects of the people. They were able to make the infernal Robespierre the first pope of Deism. It was through his mouth that the French rendered homage to the Supreme Being. The new calendar was an act of despotism forced on the people, and the festivals based on it were detestable. 1. In what ways did the National Convention attempt to change traditional French religious beliefs? Categorizing the documents: Which documents support the DeChristianization policies, which are against the policies? List the document number and a brief summary of the document under in its proper category For Against Thesis practice: To what extent were the de-Christianization policies of the National Convention successful? Remember the FUNNEL approach! Step 1: Start BROAD – you must first give background information to set the historical context *Set the stage* Specific time period & location Specific historical events/major ideas of the time period Think about the who, what, when, where, why surrounding your topic. WHY is your topic important in the big picture of history? Step 2: Get more SPECIFIC – Define any terms in prompt that need an explanation Bring in examples that support what your thesis will state Step 3: THESIS – Now you make your argument (what does the statement “to what extent” mean?)