Pragmatism

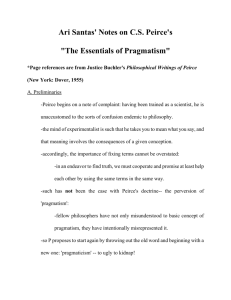

advertisement

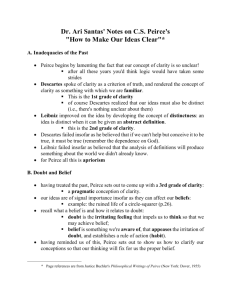

Pragmatism’s Conception of Truth: Notes Background The American semiologist and logician, Charles Peirce (1839-1914), invented the term “pragmatism”. In his essay “How to Make Our Ideas Clear”, published in 1878, Peirce introduced “pragmatism” as a method whose primary objective is the clarification of thought. The “pragmatic method” is based on the notion of belief as a rule for action. Beliefs get their meaning from the action for which they are rules. Beliefs produce habits of action and the way to distinguish between them is to compare the habits they produce. With this notion of belief the privacy and the secrecy of the Cartesian mind is bypassed and direct access gained to the mental processes we call beliefs – a person’s belief can be established by simply observing a person’s actions. There is an interesting resemblance between Peirce’s claims about beliefs and what Berkeley said about ideas: “our idea of anything is our idea of its sensible effects”. We seem to be in the presence of a form of radical empiricism as a starting point for both philosophers. William James Peirce’s essay went largely unnoticed until 25 years later William James set out to promote the doctrine of Pragmatism. Where Peirce had meant for pragmatism merely to provide a formula for making ordinary thought more scientific, James saw it as a philosophy capable of resolving metaphysical and religious dilemmas. Pragmatic Theory of Meaning In “Pragmatism”, James writes: “Is the world one or many? – fated or free? – material or spiritual? – here are notions either of which may or may not hold good of the world; and disputes over such notions are unending. The pragmatic method in such cases is to try to interpret each notion by tracing its respective practical consequences. What difference would it practically make to anyone if this notion rather than that notion were true? If no practical difference whatever can be traced, then the alternatives mean practically the same thing, and all dispute is idle.” From this thought process James derives the following principle: “There can be no difference anywhere that doesn’t make a difference somewhere.” To illustrate the pragmatic theory of meaning, let’s look at these sentences: 1. Steel is harder than flesh 2. There is a Bengal tiger loose outside 3. God exists With statements 1 and 2, it is obvious how their (pragmatic) meaning is derived. We know exactly what it would be like to believe them, as opposed to believing their opposites. For example, if believe an alternative to #1, our behavior would be radically different. The same applies to #2. The sentence #3 illustrates the subjective feature of James’s theory of meaning. Here are some options: - - If certain people believed that God existed, they would conceive of the world very differently than if they didn’t believe Some people’s conception of the world would be practically identical regardless of whether they believed in God’s existence or not. For these people, the propositions “God exists” and “God does not exist” would mean (practically) the same thing For certain other people, somewhere between the two extremes, the proposition “God exists” means something like: “On Sunday, I put on nice clothes and go to church.” For them, engaging in this activity is the ONLY practical outcome of their belief (here we see Peirce’s “belief as the rule of action”) Pragmatic Theory of Truth The pragmatic theory of truth (as proposed by James) is best understood when compared to the two other theories of truth that have competed with each other throughout the history of Western philosophy: - The Correspondence Theory o The proposition is true if it corresponds with the facts. Thus the sentence “The cat is on the mat” is true if and only if the cat is indeed on the mat Problems with the Correspondence Theory of Truth - The difficulties in explaining how linguistic entities (words, sentences) can correspond to things that are nothing like language The difficulty in stating exactly what it is that sentences are supposed to correspond to (what is a “fact” if not that which a true sentence asserts?) An awkwardness in its application to mathematics (what is it to which the proposition 5 +2 = 7 corresponds?) - The Coherence Theory o A proposition is true if it coheres with all the other propositions taken to be true The great strength of the coherence theory is that it makes sense out of the idea of mathematical truth (“5 + 2 = 7” is true because it is entailed by “7=7”, “1+6”, “”21%3”, etc.) The greatest weakness of the coherence theory is its circularity (The belief system of a paranoid person can contain a set of beliefs perfectly cohering with one another and supporting the central belief that everyone is out to get him) The pragmatic theory of truth can be seen as placing the correspondence and coherence theories into a fresh perspective: The pragmatist (James) says that the two theories are NOT competing with each other. Instead, they are just different tools to be applied to beliefs to see if those beliefs “work”. Sometimes one test is a satisfactory tool, sometimes the other, but neither is the sole criterion of truth. In James’s words: “True ideas are those that we can assimilate, validate, corroborate and verify. False ideas are those that we cannot…. The truth of an idea is not a stagnant property inherent in it. Truth happens to an idea. It becomes true, is made true by events.” Going back to our three examples: 1. Steel is harder than flesh – Believing that this is true places us in a much more satisfactory relation to the rest of our experience that believing the opposite 2. There is a Bengal tiger loose outside – For most of us, believing that this is true does not work. Believing that this is the case, at this moment, would put us in a paranoid relation to the rest of our experience (except, of course, if there indeed WAS a Bengal tiger loose outside) 3. God exists – This is more complicated. The question of truth and falsity of this claim does not even come up for those people for whom there is no practical difference whether they believe it or not. But for those for whom the distinction is meaningful, the pragmatic test of truth is available. But it is not a direct test of the sort available to us in the first two examples. Empirical evidence, according to James, is equally indecisive for or against God’s existence. What sort of pragmatic test is then available to those for whom it makes a difference whether God exists? In James’s words: “Our passional nature not only lawfully may, but must, decide an option between propositions, whenever it is a genuine option that cannot by its nature be decided on intellectual grounds.” For some people the belief in God’s existence works. For some other people this belief does not work (it induces the “paranoid” fear vis-à-vis the rest of their experiences. So, for the first group, the proposition “God exists” is true. For the second group, it is false. This subjective side of James’s theory of truth was problematic for many philosophers, including Peirce. Note: There is an interesting parallel between James and Kant. Both Kant and James tried to justify on practical grounds our right to hold certain moral and religious values that cannot be justified on purely intellectual grounds. Just as Kant attempted to mediate between rationalism and empiricism, so did James see himself as mediating between what he called the “tender-minded” and the “tough-minded” philosophers: The Tender-Minded Rationalistic (going by "principles") Intellectualistic Idealistic Optimistic Religious Free-willist Monistic Dogmatical The Tough-Minded Empiricist (going by "facts") Sensationalistic Materialistic Pessimistic Irreligious Fatalistic Pluralistic Skeptical The trouble with these alternatives, James said, was that “you find an empirical philosophy that is not religious enough, and a religious philosophy that is not empirical enough.” Obviously, James thought that his pragmatism offered a third, more satisfying alternative.