Jamie, Danika, Kai, Brooke, Navjeet, KEA

BIS 343 Community Psychology

Lauren Lichty

June 8, 2015

Homeless in Seattle

Final Paper

What is homelessness? Oxford dictionary defines homeless as “a person without a home, and

therefore typically living on the streets”. The homeless population includes many different kinds

of people from many different walks of life and happens across the globe. This paper will mainly

focus on the homeless in Seattle, but isn’t limited to just the city. Some research we found

focused on the Northwest, West Coast, and some took the US as a whole.

Homelessness ultimately impacts everyone in a community in different ways. It is important in

community psychology to analyze all the different levels in which a homeless individual

experiences community in order to find the best level of intervention necessary to help aid them

in their life struggles. Without considering even one of the different levels, or only focusing on

one level, an error of logic can occur. This means that an intervention tactic may come out

flawed and applying it to a community may damage the structure, rather than help it. For the

homeless individual there are many direct impacts of their homelessness. These are just a few:

● The individual level impacts one’s sense of well-being and how they fit into a community

greatly. After losing one’s sense of independence that comes with losing one’s residency,

it can difficult to get back into a community setting.

● On observing one’s microsystem, one’s family and friends change drastically. Without

the immediate opportunity to be in a community with built in connections, interaction

changes. Often relationships become for survival and are considered risky or unhealthy.

● Organizations often can become a lifeline for those who are homeless because they can

offer help for free. An example would be of a church handing out free meals or clothing

to those in need, or a shelter offering free housing and food.

● Locality and the resources at this level impact those who are homeless. If one lived in a

quiet neighborhood before losing their home, the scenery of one’s new home on the

streets of a city or town would be very different from their past suburban lifestyle. The

openness of the street can feel unsafe and often is unsafe. Shelters may provide sanctuary,

but they come at a cost; often the cost of privacy and being treated like a child.

● When someone is homeless, often that person loses immediate connection or access to

their macrosystem. Often government aid isn’t accessible to the homeless due to no

permanent address of residency which is required for some government programs and

aid.

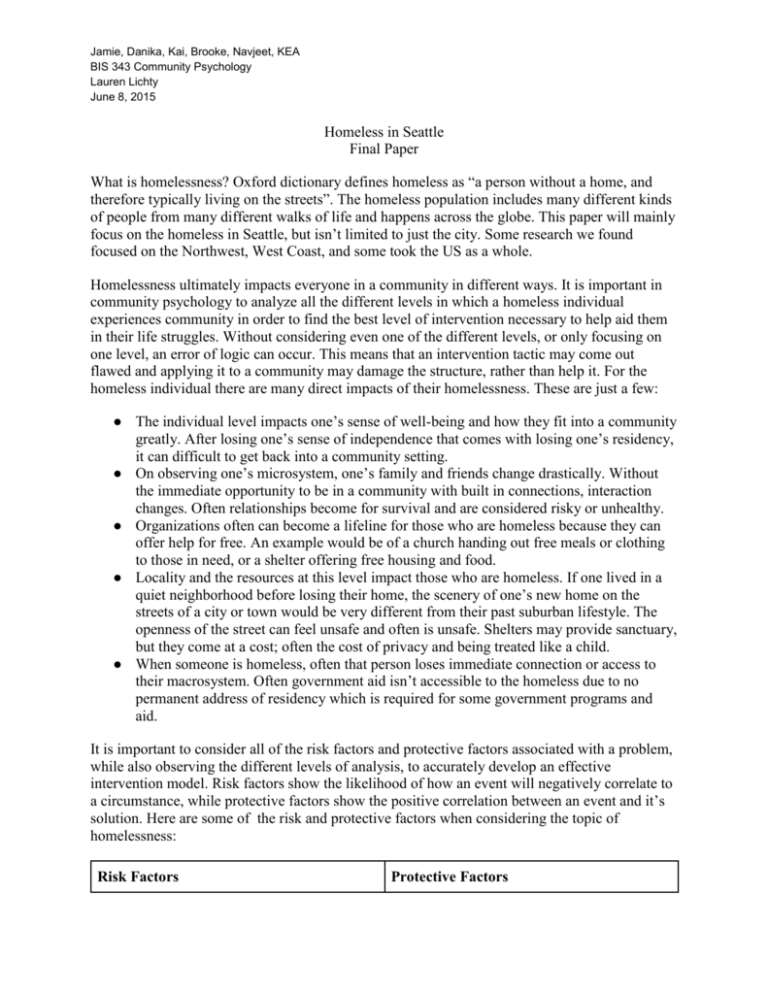

It is important to consider all of the risk factors and protective factors associated with a problem,

while also observing the different levels of analysis, to accurately develop an effective

intervention model. Risk factors show the likelihood of how an event will negatively correlate to

a circumstance, while protective factors show the positive correlation between an event and it’s

solution. Here are some of the risk and protective factors when considering the topic of

homelessness:

Risk Factors

Protective Factors

Jamie, Danika, Kai, Brooke, Navjeet, KEA

BIS 343 Community Psychology

Lauren Lichty

June 8, 2015

Sickness from exposure to elements

Shelters, housing, tent city communities

Drug use/overdose/health problems

Needle exchange, rehab centers, halfway

housing

Survival sex/prostitution/sex trafficking

*Health centers (planned parenthood STD/STI/HIV/pregnancy testing,

condoms/contraception. hospitals), shelters

Kidnapped and placed in sex trafficking

Police aid, media (wanted posters, community

search teams)

Lack of resources/access to resources: Food,

toiletries

Food aid/food programs, church donation

centers, tent city communities, soup kitchens,

Salvation Army

Physical abuse/Health problems

Helplines, police aid, health centers

STD/STI/Pregnancy/Health problems

Education, contraceptives, *health centers

Potential to drop out of education systems

Stay in school and graduate, GED programs

Violence

Learn self defense, police aid

Crime: Placement in juvenile jail/jail/prison

Non discriminatory resources, family support

Crime: Vandalism, Theft, Petty crime

Non discriminatory resources, shelters, soup

kitchens, clothing banks

Tony Sparks (2010) Broke Not Broken: Rights, Privacy, and Homelessness in

Seattle, Urban Geography, 31:6, 842-862, DOI: 10.2747/0272-3638.31.6.842

An article, Broke Not Broken, found that there have been many scholars who have closely

examined the privatization of public space. This was done through neoliberal urban policies and

planning which resulted in increasing the marginalized urban homelessness. The authors of this

article learned through their research that homeless people want the right to be eradicated from

public view. A common feeling from the homeless population is that being in public view

stigmatizes them. It has made them feel that when in a public space, they are politicized as a

visible embodiment in the form of structural injustice of capitalism and spatial injustice.

Throughout the observations, the researchers found the visibility of the homeless functions as a

signifier for social injustice, homelessness and capitalist development. The authors found that

homeless are framed as differential citizens who are often denied material privacy protections of

the First and Fourth amendments, simply based on their lack of property. Roy (2003, p. 475)

They argue it is ultimately homeless persons’ lack of access to private property and its privileges

that justifies the usurpations of privacy represented by the “spatial techniques of fortification,

eviction, and surveillance that are used to manage the homeless.” This shows the

Jamie, Danika, Kai, Brooke, Navjeet, KEA

BIS 343 Community Psychology

Lauren Lichty

June 8, 2015

marginalization of these people and their right of being considered a proper citizen is being

ignored. Although some have likened the heightened level of state intervention and management

of the homeless to the treatment of refugees, stateless persons, and illegal immigrants, the legal

citizenship status of the homeless is seldom in question (Arnold 2004).

● Homeless people do not want to be identified as homeless.

● Homelessness has signified one’s moral unfitness to exercise the right to bear citizenship·

These people do not want to be stereotyped. They often are stereotyped as drunks, drug

addicts, mentally ill, lazy, deviant, parasitic, diseased and incompetent in the public eye.

● They are treated “less-than-human” because they lack access to a “fixed and legal

residence.”

● They are treated like monitored children in shelters, having to be watched, signing in and

out and being questioned profusely.

SHARE/WHEEL shelters provide these homeless individuals the opportunity to function as

active participatory citizens through their own expression and pursuit of their collective needs

and desires.

Ensign, J. (2004). Quality of Health Care: The Views of Homeless Youth. Health Services

Research, 39(4p1), 695-708. DOI:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00253.x

This article summarized an ethnography done in 2002 on homeless youth from

both street and clinic settings in Seattle, Washington. The purpose of this research was to find

what kind of health care would be most useful and effective for the homeless youth population.

The ethnography was a series of in depth individual interviews, as well as focus groups with a

sample of 47 homeless youth aged 12–23 years. “All interviews and focus groups were tape

recorded, transcribed, and preliminarily coded, with final coding cross-checked and

verified with a second researcher.”

The findings were that homeless youth most often stated interpersonal aspects of health care and

other resources as being important to them. “Physical aspects of care reported by the youth were

health care sites separate from those for homeless adults, and sites that offered a choice of

allopathic and complementary medicine.” This resulted in many positive outcomes, including:

survival of homelessness, improvement of prevention and treatment for diseases, decrease in

disease rates amongst homeless youth, and increased trust with adults and the wider community.

As a result, homeless youth more likely to reach out for health care, instead of turning to things

such as substance abuse or survival sex.

This article was chosen because it integrated the community psychology models of research,

collaboration, integration, and intervention really well. The research was done in collaboration

with the homeless youth community, to hear and integrate their perspectives. This collaborative

approach was taken in order to effectively reform health care systems available to homeless

youth. Scholarly articles specifically on runaway youth were very difficult to find, even though

large portion of homeless youth are runaways. Besides the select few in the 20-23 age range that

were homeless for economic reasons such as lack of housing, jobs, etc.

Jamie, Danika, Kai, Brooke, Navjeet, KEA

BIS 343 Community Psychology

Lauren Lichty

June 8, 2015

In a federal estimate, Seattle is believed to have the fourth largest homeless population in the

country, after Los Angeles, Las Vegas, and San Francisco. A large portion of that are youth or

young adults. The number is approaching an estimated count of 1,000 just in King County.

Experts believe that at least half are runaways, according to Komo. In a national estimate, it was

projected that approximately 1.3million runaway youth live unsupervised, either in the streets or

in “unstable housing” such as couchsurfing. Sadly, around 5000 unaccompanied youth die each

year as a result of assault, illness, or suicide; states the National Council of State Legislatures

(NCSL). According to the 2003 national study done by the NCSL, statistics show that 1/7 youth

ages 10-18 will runaway and youth ages 12-17 are more at risk of being homeless than adults

Despite the frequently stigmatized story surrounding homeless youth, runaway situations often

has very little to do with the individual and has more to do with the intersectionalities of

microsystems, organizations, localities, and/or macro systems surrounding that individual. The

top 3 reasons for running away are:

● Family problems which include (46%) physical abuse, (38%) emotional abuse, (17%)

sexual abuse. There are sometimes just one kind of abuse, however often it is a

combination of these types of abuse that are experienced by the runaway.

● Transitions from foster care and other public systems can leave individuals without

residency and a lack of income to support themselves. Once released from foster care

youth are on their own. Because of admission policies, youth are often not admitted to

shelters, which are just for adults. This puts more youth on the streets than adults and

denies youth access to resources.

● Economic or financial reasons such as difficulty obtaining and maintaining jobs, lack of

affordable housing, and lack of healthcare or other benefits.

In the May of 2015, KOMO News covered a story on runaway youth in the Seattle area. One of

the interviews was with a 23-year-old young adult named Matthew. He had been a homeless

runaway for four years. He told the reporters that when he was a kid, his mom, dad and brother

had all died. Rather than turn to relatives, he turned to the streets, heroin and methadone. KOMO

News asked him: "Matthew, what do you want people to know about the plight of young people

on the streets?" To which Matthew answers: "It's not a game. It's real. Yeah. You look at us like

it's our fault. You know, he must've done something for him to be out here, you know. But I

didn't do anything wrong for me to be out here. It just happened."

Analyzing this from a community psychology lens, these stories are important to keep in mind

for integrating prevention and promotion strategies. These studies and statistics illustrate the

dangers of “a single story” and how a single perspective of a condition can result in severely

damaging a community. One example of this is the recent installment of “anti homeless spikes”

placed under bridges or in other parts of the city that serve as resting spots for homeless

individuals. The goal was to reduce the amount of litter around business buildings. In this case,

the root cause of the issue was misunderstood. Instead of addressing issues that cause

homelessness in the first place, such as lack of affordable housing, lack of jobs, or lack of other

resources; the homeless population was identified as the direct cause of the problem instead, and

spiked were installed to get rid of the “problem”. Manchester resident Cathy Urquhart, who

started a petition against these spikes on Change.org, wrote: “These spikes are an affront to

Jamie, Danika, Kai, Brooke, Navjeet, KEA

BIS 343 Community Psychology

Lauren Lichty

June 8, 2015

humanity. They tell the homeless that they are not welcome, that they are a problem to be moved

on.” Likewise, common social stigmas around runaways youth, such as “lazy”, “juvenile” or

“lacking in discipline”, could result in making the runaway population feeling oppressed and

misunderstood. This in turn could make them less likely to reach out to resources, and more

likely to turn risky behaviors for the sake of survival.

This second example is of a tertiary prevention method that was integrated in collaboration with

the runaway youth population and resulted in more effective and positive change. The prevention

began with a research ethnography done with homeless youth from both street and clinic settings

in Seattle, Washington in 2002. The purpose of this research was to find what kind of health care

would be most useful and effective for the homeless youth population, and was conducted as a

series of individual interviews. The findings were that homeless youth most often stated

interpersonal aspects of health care and other resources were important to them. According to

Ensign, “Physical aspects of care reported by the youth were health care sites separate from those

for homeless adults, and sites that offered a choice of allopathic and complementary medicine.”

Outcomes of these types of health care were survival of homelessness, improvement of disease

or decrease in disease rates amongst homeless youth, and increased trust with adults and with the

wider community making those homeless youth more likely to reach out for health instead of

turning to things such as substance abuse or survival sex (Ensign).

"DESC - Shelter, Housing and Services for Homeless Adults in Seattle."DESC - Shelter,

Housing and Services for Homeless Adults in Seattle. N.p., n.d. Web. 07 June 2015.

In today’s generation we are seeing more and more homeless people out on the streets: has the

numbers of homelessness increased or are they being forced into more concentrated spaces as

they are being pushed out from others? More importantly, are they being helped with their

needs? DESC “opening doors, ending homeless” organization has helped people since 1979.

They help adults who are helpless living with behavioral health disorders and chronic

homelessness. Everyday 2,000 homeless women and men look for the help of DESC but, help is

only provided to those who are in the need of crucial assistance. Numerous times homeless

people are refused and rejected for help because DESC is specifically designed for the homeless

folks that are in fragile need and help. DESC has given many people the hopes of dreaming

again, with the powerful help of providers. Their mission today is not only to offer shelters to the

homeless but to end homelessness in the community we live in today. Their initial operating

style was first-order change. They provided people who needed housing a space to lay their head

down. They have adjusted their perspective to recognize the issue grows deeper than just a

pillow for the night. This new perspective on the homeless conundrum shows potential for

second order change by trying to connect the homeless that come through their doors with

resources to get jobs, and affordable housing options.

VAN LEEUWEN, J; et al. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual homeless youth: an eight-city public health

perspective, Child Welfare. 85, 2, 151-170, Mar. 2006. ISSN: 0009-4021

With the count at approximately 1.6 million homeless youth in the United States each year, it’s

important to take this topic with care. This article shows the specific needs that LGBTQ

Jamie, Danika, Kai, Brooke, Navjeet, KEA

BIS 343 Community Psychology

Lauren Lichty

June 8, 2015

homeless youth have compared to their non-gay homeless youth counterparts. The reasoning

behind these extra needs is because in contrast to their non gay counterparts, LGBTQ homeless

youth face a number of added problems including drug use, survival sex (prostitution), physical

and sexual abuse, mental illness, increase in HIV risk, and increased suicide rates. All of these

added problems lead to increased stress levels. By adding resources specific to their needs, they

can then develop better coping methods to battle additional stress. Stress can be broken up into

two different levels of stress: distal contextual factors, and distal personal factors.

Distal contextual factors are those that, “include ongoing environmental conditions that may

interact in various life domains” (Kloos, 255), while distal personal factors can be described as

individual conditions that aren’t easy to see at first. Often they are problems that the individual

doesn’t voluntarily control, such as specific attributes or genetics. What these both have in

common is that they can both act as stressors or resources in an individual’s life. Homeless

LGBTQ youth are experiencing a mix of distal contextual factors and distal personal factors that

add up to a strong sense of stress in their lives. Their largest distal contextual factor they face

would be their inability to find a home and societies lack of view of diversity among sexualities.

Their toughest distal personal factor would be the fact that they identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual,

transgender, queer, or something else. The article concludes by saying that the additional needs

of LGBTQ homeless youth should be observed and studied deeper by child welfare services to

build additional resources or coping additional coping methods, specific to the needs of LGBTQ

homeless youth.

Unlike the homeless adult population, homeless youth are often discriminated against or

withheld access to resources such as high-paying jobs with benefits, health insurance, savings,

and other community resources (Zerger, 824-5). Lack of these fundamental resources leads

homeless youth to engage in risky sexual behaviors in exchange for basic necessities like food,

water, clothing, and shelter (Zerger, 825). These behaviors often times lead to physical and

sexual violence and drug abuse (Zerger, 830). An estimated 70-97% of homeless youth reported

abuse drug and/or alcohol (Zerger, 832). Depending on their age and the duration of their

homelessness, that number increases (Zerger, 832-3). The population of homeless youth who are

also struggling with addiction is both common and very high, however engagement in any type

of drug or alcohol treatment has been very challenging (Zerger, 833). Part of the reason is

because treatment is often times not sought or homeless teens leave treatment before having fully

recovered (Zerger, 833). Studies show through organizational prevention programs, both

homeless and runaway youth have reported reduced drug dependence (Zerger, 830).

Homeless youth are often underrepresented in studies since the term homeless only encompasses

those who are actively using services like shelters and clinics (Zerger, 826). Few of these studies

address the “hidden” homeless population: those staying with friends or living in substandard

housing (Zerger, 826). Homeless youth are also overrepresented (Zerger, 835). They are clumped

into the same category as immigrants, racial and sexual minorities, physically and sexually

abused victims, emancipated youth, and those who are “aging out” of foster care (Zerger, 835).

Jamie, Danika, Kai, Brooke, Navjeet, KEA

BIS 343 Community Psychology

Lauren Lichty

June 8, 2015

SOURCES

Burnside, J. (2015, May 7). Stories of homeless teens: 'I didn't expect myself to be a

runaway' Retrieved June 8, 2015, from http://www.komonews.com/news/local/Youthhomelessness-on-the-rise-in-Seattle-I-didnt-expect-myself-to-be-a-runaway-303008431.html

Covert, B. (2015, February 18). Department Store Installs 'Anti-Homeless' Spikes.

Retrieved June 8, 2015, from http://thinkprogress.org/economy/2015/02/18/3624021/selfridgeshomeless-spikes/

"DESC - Shelter, Housing and Services for Homeless Adults in Seattle."DESC - Shelter,

Housing and Services for Homeless Adults in Seattle. N.p., n.d. Web. 07 June 2015.

Ensign, J. (2004). Quality of Health Care: The Views of Homeless Youth. Health

Services Research, 39(4p1), 695-708. DOI:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00253.x

Homeless and Runaway Youth. (2013, October 1). Retrieved June 8, 2015, from

http://www.ncsl.org/research/human-services/homeless-and-runaway-youth.aspx

Tony Sparks (2010) Broke Not Broken: Rights, Privacy, and Homelessness in

Seattle, Urban Geography, 31:6, 842-862, DOI: 10.2747/0272-3638.31.6.842

VAN LEEUWEN, J; et al. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual homeless youth: an eight-city

public health perspective, Child Welfare. 85, 2, 151-170, Mar. 2006. ISSN: 0009-4021

Zerger, S., Strehlow, A., Gundlapalli, A. (2008). Homeless Young Adults and Behavioral

Health. American Behavioral Scientist, 51, 824-841.