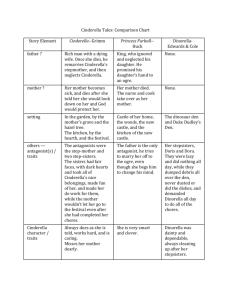

Charles Perrault (1628

advertisement