-Cats: if develop hemolytic anemia post bite wound, consider FIV

CE Notes: CSU Veterinary Conference 2014

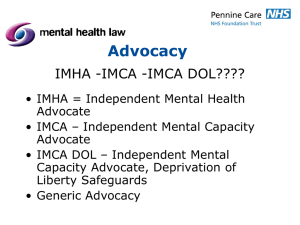

IMHA Review

Intravascular – complement mediated, uncommon with primary IMHA

Red cell intravascular lysis

This type of IMHA is generally more severe and difficult to treat

Free Hgb can damage kidneys

IMHA treatments are targeting macrophages in tissues, so animals with intravascular IMHA won’t respond as well to therapy

-

Hemoglobinuria (port wine color), hemoglobinemia (pink serum)(won’t change color when spun down)

Extravascular – phagocytosis by macrophages in spleen and liver, much more common

Tend to be easier to treat

Have elevated bilirubin from Hgb breakdown, not free Hgb

Hemolysis can occur in spleen, liver, bone marrow or lung (one reason why splenectomy is not always effective – because hemolysis will still occur in other tissues)

Jaundice, hyperbilirubinemia, hyperbilirubinuria

Canine IMHA –

Dogs can have intra and extra vascular hemolysis simultaneously or convert from one form to another

Differentials for hemolysis in the dog: immune mediated, erythroparasites

(babesia), microangiopathic hemolysis, Heinz body anemia, zinc induced, inherited defects (Basenjis)

Feline IMHA –

Differentials for hemolysis in the cat: FeLV, Mycoplasma haemofelis, hypophosphatemia, Heinz body anemia, IMHA (usually secondary; primary is extremely rare)

Secondary IMHA – consider infection, medications (TMS, thyroid meds), neoplasia, vaccines

IMHA general points –

IMHA generally causes anemia without hypovolemia or hypoproteinemia

Can occur without jaundice, hemoglobinemia/uria

Mild to moderate to severe anemia without jaundice is common unless there is concurrent liver disease (liver can usually process the bilirubin)

PCV <20% tends to cause hemic murmur

Tissue hypoxia triggers sympathetic nervous system

bounding pulses, tachycardia, tachypnea, mental dullness; if pulses are weak (consider blood loss over IMHA)

IMHA

massive inflammatory disease

splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, fever, anorexia, mild lymphadenopathy (20-25% of cases), leukocytosis

Next to leukemia, IMHA has the highest level of leukocytosis

IMHA complications –

80% that go to post mortem have PTE

development of dyspnea in IMHA patient is nearly always due to PTE

DIC is rare – low platelets are usually due to embolism or immune destruction; bloodwork parameters seen with embolism often mirror that seen with DIC

May suddenly develop ascites – generally due to vasculitis or PTE

IMHA diagnosis –

Regenerative anemia usually (unless early, regeneration takes 3-5 days)

Normal blood volume and serum protein

Sometimes spherocytes (negative for many IMHA cases), bilirubinemia

Spherocytes generally equal immune mediated disease; very rarely seen with snake bites and zinc toxicity

-

IMHA can be non regenerative, either because it’s early or bone marrow is affected (affected bone marrow is more common with primary IMHA); up to 1 in

3 IMHA patients have a poor retic count

Pure red cell aplasia – may be only in the marrow with no evidence of peripheral hemolysis

Aplastic anemia – all cell lines affected

Saline agglutination test – this test should not be run with cold blood or cold saline (cold temperature can cause agglutaination or hemolysis)

Severe agglutinating IMHA (like intravascular IMHA) is harder to treat and carries a worse prognosis – fortunately both of these types are relatively uncommon

IMHA workup –

CBC with smear to evaluate for spherocytes (in dogs), parasites, Heinz bodies, schistocytes, retic count

Evaluate smear immediately for parasites (all cats should be treated with doxy; infectious is very rare in the dog, but chance increases depending on geographic region, if splenectomized, and if grey hound or pit bull)

Slide agglutination - 1 drop EDTA red blood cells + 1 drop room temperature saline in dogs (use 3-4 drops in cats)

If (-) for slide agglutination, cannot rule out IMHA

Coombs test – quality of the test varies greatly, only run if really unsure of diagnosis (if positive, most likely IMHA; if negative, you cannot r/o IMHA)

Bad cases of IMHA will usually have elevated ALT due to ischemic injury to the liver (rather than primary liver disease)

Further testing – imaging (screen for neoplasia, other), retrovirus (cats), rickettsia/protozoal (dogs), coagulation testing

Patients that are <1 year of age, >8 years of age, or feline should receive a more thorough workup

IMTP Review

General notes

In dogs, IMTP is the most common acquired bleeding disorder

Dogs – IMTP is usually primary; secondary causes are similar to list for IMHA, with Rickettsial disease being higher on the list

Cats – IMTP is usually secondary (infectious, lymphoma)

Antibodies bind to the platelet surface, so platelet function is affected in addition to platelet count; lifespan of a platelet in IMTP is 1-2 hours (vs 1 week for normal platelet lifespan)

Spectrum of disease: o Classic IMTP

o Megakaryocyte aplasia (don’t respond well to treatment; diagnosis via bone marrow) (usually other cell lines are affected as well; but rarely only the megakaryocytes are affected) o Compensated thrombocytolysis (eg platelet count is at 100,000, no bleeding; have immune disease but patient is compensating) o Platelet dysfunction (bleed with okay platelet numbers)

Clinical signs: petechia, ecchymosis, gingival bleeding, hematemesis, hematuria, epistaxis, melena, hematachezia

Patients can still clot – can see significant urinary tract clots

Most common cause of death: 1. hypovlemic shock due to GI hemorrhage, 2. intracranial hemorrhage

Causes of platelet destruction – immune mediated, infectious (RMSF, babesia,

Ehrlichiosis (but usually not severe thrombocytopenia)), DIC

Evaluation of thrombocytopenia

Always look at a smear – CBC can falsely decrease counts (giant platelets are counted as rbc or lymphs and clumped platelets aren’t counted), especially in cats

Very few things can falsely elevate the platelet count on CBC

Estimate off a smear – normal is 10-30 plt/hpf

Each platelet per hpf is equivalent to a circulating platelet count of 15-20 x 10

9

/L

Cavaliers have macrothrombocytes and can have pseudothrombocytopenia (with a falsely elevated lymph count); reported rarely in other breeds

Diagnostic approach

First tier: CBC, Chem, Coags, d dimmers, Rickettsial serology +/- babesia

Second tier: imaging, retroviral serology (cats), bone marrow

Confirmatory tests – only useful one is the platelet-bound antibody levels offered at Kansas State, but offered intermittently

Consider secondary causes if not responding to treatment, <1 yr, >8 yrs of age, or cat

Immune Mediated Polyarthritis

General info

Usually very pred responsive

In dogs, estimate that >80-90% of polyarthritis cases are immune mediated o Non erosive is much more common; estimate <1% are erosive o Estimate that <10-20% of cases are infectious (depends on geographic region) (E. canis, Lyme)

In cats, infectious causes are much more common and erosive lesions are more common

Presentation: the most common presenting complaint is fever; often these patients do not have lameness; however, you may detect joint effusion; Without swelling or lameness, the only clinical sign may be decreased range of motion;

Polyarthritis is a very commonly missed cause in FUO cases

Carpi and tarsi most affected

Diagnostics:

CBC

Chem with CK (can have syndrome with polyarthritis and polymyositis together)

UA with urine culture

SNAP test – heartworm, Lyme Rickettsial

Retroviral testing in cats (foamy virus in cats can cause polyarthritis and is often picked up on FeLV/FIV snap)

Predictable results:

Inflammatory or stress leukogram

Anemia of chronic disease

Mild hypoalbuminemia (negative acute phase protein)

Mild to marked hyperglobulinemia

Mature neutrophilia is common

R/O – Hepatozoon (muscle pain, some bone pain, polyarthritis)

Further diagnostics, recommend tapping:

2 small joints (carpi) – most commonly affected with immune mediated disease

And 2 large joints (stifles) – most commonly affected with infectious disease o If large joints are inflamed with normal small joints – immune mediated disease is very unlikely

-

Plus any joint that’s swollen o If only one joint is inflamed – usually infectious

Cytology can look the same in non-erosive IMP, erosive IMP or infectious

(healthy neutrophils); vs degenerative joint disease (mononuclear cells)

Culture – generally low yield; highest yield if collected in blood culture tube rather than a swab

Etiologies

Type I – uncomplicated, no underlying disease, most common

Type II – Reactive, formed immune complexes elsewhere, ie Lupus, Lepto,

Lyme, heartworm, Rickettsial disease, Bartonella, endocarditis

Type III – Enteropathic, formed immune complexes elsewhere, ie IBD, parvo, pancreatitis, food allergy, leaky bowel (showering antigen)

Type IV – neoplasia

Can also see secondary to drugs, especially TMS

Additional notes:

Concurrent neck pain

1 in 3 patients with IMP has cervical pain

Consider a sterile meningitis concurrent with IMP – the meningitis will respond to steroid therapy

R/O discospondylitis, which can shower bacteria to the joints

Erosive polyarthritis

Most common in small, middle-aged dogs

Additional diagnostic tests:

Rheumatoid factor – rarely useful; recommended for cases with polyarthritis, erosive, and negative for infection

ANA – test for ANA only when SLE is possible diagnosis

Run when multiple systems are affected by immune mediated disease

Urine culture – in infectious polyarthritis, urine culture is the most likely culture that will be positive

Infectious vs Immune Mediated (Lappin notes)

Cats: if develop hemolytic anemia post bite wound, consider FIV and hemoplasmosis (Mycoplasma haemofelis)

Hemoplasmosis: transmission through direct contact (cat fights), sick within 17 days, treat with doxycycline (10 mg/kg q24h for 7-28 days), life threatening cases or rescue cases treat with Baytril; up to 50% falsely negative on cytology

(especially if not immediately reviewed)

Pradofloxacin is an option for cats with better ocular safety than Baytril (7.5 mg/kg q24h) up to 28 days

Immune Complex disease

affects joints, eyes, kidneys (do an antigen search)

Uveitis and lameness in cats:

immune mediated disease, FIP, FeLV (uveitis is usually due to lymphoma), FIV,

Ehrilichia, T. gondii, C. neoformans, Bartonella henselae, FHV1

If they have uveitis without conjunctivitis – give pred

Best toxoplasmosis screening tool: IgG and IgM o PCR is NOT recommended – costs more money and healthy animals can be (+); save PCR for BAL and CSF testing o Serology is especially useful if negative to rule out disease

In general, when struggling whether disease is infectious vs immune mediated, treating with pred is advised UNLESS you’re suspicious of lepto, septic, bacterial endocarditis or protozoal infection (Neospora worsens dramatically with steroids) o RMSF, lepto and sepsis can have a similar presentation – treat with doxy, Baytril

+/- ampicillin o Most common causes of bacterial endocarditis: staphs, streps, E coli and

Bartonella

Immune Mediated Blood Disorders: Emergency Management

Mortality rates:

Usually low for IMTP

Around 50% for IMHA

Poorer if IMHA + IMTP

-

½ pass during initial episode due to anemia, hypovolemia, PTE*

Treatment aims:

Remove underlying cause if secondary

Immunosuppressive therapy

Transfusion

Other (see below)

Immunosuppressive therapy:

Steroids

+/- azathioprine, cyclosporine

Chlorambucil – effective in cats

Leflunomide – IMP in dogs

Steroids

Prednisone: recommend 2 mg/kg per day orally

>2 mg/kg/day is NOT more immunosuppressive and not recommended

Can go up to 2 mg/kg BID in cats

Dexamethasone: recommend 0.1-0.6 mg/kg once daily

-

No evidence that it’s better than prednisone

However, occasionally patients respond differently to different steroids, so may want to try dex if not responding well to pred

Also useful if vomiting and needing an IV drug

When to add a second agent:

Prednisone takes 7-10 days to take effect

Other agents take 1-2 weeks to take effect

-

Recommend a second agent if there’s bad disease, eg severe anemia, severe thrombocytopenia, transfusion dependent, intravascular hemolysis, hypovolemia, strong agglutination

If mild disease, recommend using prednisone as sole therapy

Management:

Minimize trauma – don’t place catheter unless necessary (IMHA), don’t over monitor bloodwork, use small needles, etc

Transfusion – see below

Fluid therapy

Not recommended with IMHA; remove catheters after transfusion, usually these patients don’t need fluids

Exception is patients with intravascular hemolysis where Hgb is causing kidney injury or bad ischemic injury (elevated ALT)

-

IMTP: recommend maintaining a catheter so you’re ready to bolus fluids if there’s a large bleed; hypovolemic shock is usually what leads to death

Oxygen therapy

Hgb is already saturated – usually need more Hgb, not oxygen

Exception is PTE – need oxygen support

Vincristine – useful for IMT

Platelet survival time increases from 1 hour to 1 day

Also have a transient surge in platelet release from the bone marrow

Tends to decrease hospitalization time (3 days with vincristine vs 5 days with pred alone)

Liposomal clodronate –

Knock out monocytes and macrophages, which ingest lipid

Used for histiocytic disease

Can be useful for IMHA if nonresponsive to typical therapy

Very expensive (eg $1600 for greyhound), very limited availability

IV immunoglobulin

Concern that pro-thromboembolic, avoid with IMHA

Have had individual positive results with IMTP; however, IV immunoglobulin tends to have similar result to vincristine (out of hospital in 3 days vs 5) but immunoglobulin is much more expensive

Splenectomy

-

Patient often isn’t stable enough for surgery

Sometimes the MPS elsewhere in the body (liver) may take over for spleen

Transfusion guidelines – be conservative

Recommend waiting until PCV is 10-15% for acute disease or 8-12% for chronic disease, or extreme lethargy

IMHA – reach for pRBCs and avoid plasma

IMTP – fresh whole blood, need plasma and volume

In 2 nd week of therapy, only use universal donor blood

PTE prevention

Avoid risk factors (IVIG, jug caths)

Cyclosporine may increase risk of PTE – avoid with IMHA

Heparin therapy –

Difficult to dose; best to titrate based on antifactor Xa activity

LMWH (enoxaparin) is recommended at standard dose: 0.8 – 1.0 mg/kg

SC QID (often reduce to BID)

Recommend aspirin and plavix

Aspirin: 1 mg/kg once daily

And/or plavix: 1-3 mg/kg daily if solo, or 0.5-1 mg/kg daily if in combination with aspirin

Recommend plavix and aspirin for 1 month

Immunosuppresive Agents

Glucocorticoids

Starting dose: 2 mg/kg/day in dogs, 2 mg/kg BID in cats o Cats tolerate high doses of steroids much better than dogs, although possibly increases risk of diabetes (reversible if caught early)

Aim for a maintenance dose of 0.5 to 1 mg/kg every other day

this dose is tolerated longterm; otherwise, add a second agent

Cyclophosphamide

Not Recommended – non specific (affects many cell types), not very potent in dogs

Side effects – myelosuppression (dose dependent and cumulative), GI disease, alopecia, refractory cystitis or bladder neoplasia** (breakdown product is very irritating to bladder; could use with Lasix, encourage drinking)

Recheck CBC two weeks after starting, then monthly

Very inexpensive

Chlorambucil

Indicated for IBD in combo with pred

Tablet size makes it convenient for cats

Only recently being used more in dogs

Same side effects as cyclophosphamide, except no cystitis; also, occasionally in cats it can cause neurologic signs

Very expensive

Azathioprine

Little cheaper and usually well tolerated; good choice in larger dogs

Works in about 1 week

Dosing in cats – need much lower dose in cats; has a low margin of safety and generally not recommended (we have much better and safer options)

Dog side effects: decreased rbc production (normal PCV 28-32), myelosuppresion, hepatotoxicity, pancreatitis; myelosuppression and hepatotoxicity can be severe and reversible, tend to be idiosyncratic reactions rather than dose dependent; severe side effects are rare and will usually occur within the first week of therapy

Check CBC and Chem at 2 weeks

Once in remission, begin to taper either the pred or azathioprine (whichever is causing more side effects) every two weeks; monitor response prior to each dose reduction; once at an acceptable maintenance dose, continue therapy for 6-12 months; prefer partial resolution of disease over side effects

Give all therapies two weeks before deciding that they’re not working

Cyclosporine

Recommended for nonregenerative IMHA

There is great variability from dog to dog in what dose is needed to achieve immunosuppression; it’s primary function is to inhibit T cell function; an assay at

Mississippi State has been developed to measure T cell IL2 so that you can target the dose

Use in combo with Ketoconazole – turns off P450 system, may use lower dose of

Atopica

Side effects: nausea* (freeze; better to give without food), gingival hyperplasia

(may improve with oral rinse or clindamycin, or may need to discontinue), hepatotoxicity/nephrotoxicity (idiosyncratic), not myelosuppressive

**predisposes to thromboembolism – not recommended in IMHA (unless occurring at level of the bone marrow) o Cyclosporine turns on platelets and enhances procoagulant activity; increases thromboxane in humans (marker of platelet activation)

Do not use compounded, however liquid formulation of Atopica is good; great agent for cats

Also a great drug for IBD

Leflunomide

Recommended for polyarthritis

Can affect marrow and cause hepatotoxicity

Mycophenylate

Never use in combination with azathioprine (same mechanism of action)

Used as an alternative to azathioprine if patient has developed hepatotoxicity

Not recommended over azathioprine for IMHA

Can cause severe GI side effects

Transfusion Medicine

Notes:

2,3 DPG depleted in stored blood; not as effective at unloading oxygen

Oxyglobin: causes vasoconstriction because of NO scavenging; can really decrease cardiac output; really useful if pathologic vasodilation, like with heat stroke or sepsis

Plasma transfusions: only if elevated PT/aPTT and bleeding

FLUTD

Etiology

Idiopathic cystitis 63%

Urolithiasis 10%

UTI 12% (older cat population; rarely the cause in younger cats)

Interstitial cystitis

Urine is usually highly concentrated, sometimes very acidic, often hemorrhagic, wide range in wbc count, pyuria identified in 3-77% of cases but not usually due to infection, crystalluria 25-48%

Etiology: infectious agents <2% of cases, leaky urothelium, mast cell activation, neurogenic inflammation, stress

1 st time offenders: recommend UA +/- culture, radiograph to rule out stones

Repeat offenders: UA, culture, ultrasound

Treatment

**rate of reobstruction is 2.5x greater with use of 5 Fr catheter vs 3.5 Fr; recommend 3.5 Fr and try to pull urinary catheter within 36 hrs max

Topical glucosaminoglycans: empty bladder, administer 2.5 mls A-CYST; perform 3 times over initial 24 hours; occlude the catheter for 1 hour following treatment

Alpha adrenergic antagonists (prazosin, phenoxybenzamine) – prazosin is 1 st choice

Steroids probably not helpful

NSAIDs – anectodal evidence that NSAIDs are helpful, but no documented evidence of improved outcome

Opioids recommended

Chronic treatment

Glycosaminoglycans

Amitriptyline, decreases detrusor activity, decreased His release, antispasmotic, anti-inflammatory activity, analgesia; no evidence that it improves outcome in the short term

Canned food

Parvo Outpatient therapy

Anti-emetic therapy

Cerenia, recommended if > 8 weeks old

Can be used up to 14 days safely; will go out for more than 5 days in parvo patients if needed

Zofran, for young patients or patients needing an additional antiemetic on top of

Cerenia

0.5 mg/kg IV TID

Cerenia IV dosing

Causes a transient decrease in blood pressure and nausea if given too quickly

Decreases the drug’s half life in half (may have break through vomiting toward the end of the 24 hour period)

Antibiotics

Recommend cefoxitin at 22 mg/kg TID if hospitalized

Cefovecin 8 mg/kg SQ if outpatient

Feeding

Hold food for 12 hours, then begin force feeding if outpatient or place feeding tube

Syringe feeding: 1 ml/kg PO QID a/d

Analgesia – buprenex IV or SQ

Tips for successful outpatient protocol:

Need to stabilize with shock IV fluids before transferring to outpatient (even if only hospitalized for 1-2 hours for bolus)

Aim for 120 ml/kg/day Norm R – 40 ml/kg TID unless not absorbing it

Replace dehydration over 24 hours + losses

Recommend measuring lytes and glucose daily

*have owners monitor temp at home and maintain patient >99 o

using heat support, or they will never absorb their sub q fluids

Treat hypoglycemia if <80; if outpatient, administer 1-5 ml Karo syrup bucally q

4-6 hours

Potassium support for outpatient protocol: 0.5 – 1 t/10 lbs Tumil K q 4-6 hrs

Arterial thromboembolism

Notes

About 50% of patients are in CHF on presentation with ATE

Difficult to distinguish tachypnea due to CHF vs pain

Often start Lasix, even if cant get radiographs

-

Recommend echo (though not an emergency), to ensure there isn’t still a thrombus in the left atrium that will cause an additional event (in this case, want to use a thrombolytic agent)

Thrombolytic therapy

TPA – more effective on fresh thrombus; less effective by 12-24 hr

Does not improve overall survival rate

High incidence of reperfusion injury

Anticoagulant therapy

Preventing extension of a clot

Heparin, unfractionated

Not recommended, dose is too variable; need to monitor effect via aPTT

LMWH

Dosed by body weight

We do not know ideal frequency but generally done BID, one study recommended TID dosing

Warfarin

Oral anticoagulant in people

Need to monitor PT very closely and highly dependent on diet and other meds

Very challenging to use

Dabaqatrin and apixaban – oral form, don’t have the diet and med variability seen with warfarin; less monitoring required; on going study at CSU

Antiplatelet therapy

Prevent extension of thrombus

Aspirin

Plavix 18.75 mg/cat daily

Longer time to recurrence when treated with Plavix vs aspirin

Prognosis

Poor prognostic factors: both rear limbs affected, severe pain, hypothermic, no motor function, CHF

Treatment recommendations

Powerful opioid, methadone recommended; buprenex is not potent enough

Oxygen, lasix +/- radiographs

Plavix +/- aspirin +/- LMWH

Outcome

Survival to discharge 35-45%

65% of treated cats died/euthanized within 24 hours

12% survival beyond 7 days