Accepted Version (MS Word 2007 53kB)

advertisement

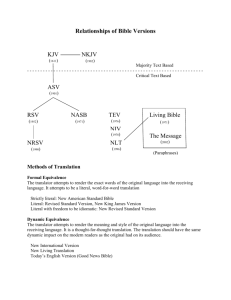

Incorporating translation in qualitative studies: Two case studies in education Authors’ names: Agustian Sutrisno, Faculty of Education, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia Nga Thanh Nguyen, Faculty of Education, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia Donna Tangen, Faculty of Education, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia Correspondence datails: thanhnga.nguyen@student.qut.edu.au, Room 354 B Block, Kelvin Grove campus, Faculty of Education, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia Abstract: Cross-language qualitative research in education continues to increase. However, there has been inadequate discussion in the literature concerning the translation process that ensures research trustworthiness applicable for bilingual researchers. Informed by Squires’ (2009) evaluation criteria for qualitative data translation, this paper compares two different procedures for incorporating translation in education qualitative research to provide a clear depiction of the complexities involved in translating qualitative data and the strengths and weaknesses of each procedure. To maintain the trustworthiness of the qualitative research, it is necessary to minimise translation errors, provide detailed accounts of the translation process, involve more than one translator, and remain open for scrutiny from those seeking to access the translation process. Taking into account the resource constraints often faced by novice bilingual researchers, this paper provides some strategies that can be employed in similar contexts. Introduction As the world becomes more globalised, research often crosses national and linguistic borders (Guest, Namey, & Mitchell, 2013). There are a growing number of researchers with research locus outside their country of origin. Included in this category are a significant number of international research students studying in countries where English is the dominant language and culture (UNESO Institute for Statistics, 2011). In these situations, there are research areas that demand the use of more than one language. For example, the research proposal may be written in English but the data were gathered in another country such as Indonesia or Vietnam using the local language. Translation needs to be employed in such research but the question then becomes: how efficiently is the translation of data done so as not to compromise the research? At the onset of this paper, it is necessary to introduce some key terms used. First, cross-language research refers to research involving a translator at any stage during the research process (Temple, 2002). This cross-language research may be done by mono-lingual or bilingual researchers. Monolingual researchers do not have working knowledge regarding one of the languages used in crosslanguage research; whereas bilingual researchers are proficient in two languages used in the research (Liamputtong, 2010). Another key term, linguistic equivalence refers to the similarity between linguistic expressions in one language and their translation in another (Loos et al., 2004). In general, satisfactory discussion about translation procedures employed in social science research is quite limited (Douglas & Craig, 2007; Liamputtong, 2010). In particular, cross-language qualitative studies are often not accompanied by sufficient explanation of the translation procedure employed to demonstrate the trustworthiness of the research findings (Fryer et al., 2012; Larkin, de Casterlé, & Schotsman 2007; Wong & Poon, 2010). Lincoln and Guba (1985) view trustworthiness as the degree of rigour in qualitative studies. In cross-language qualitative studies, trustworthiness does not only concern the research process and findings but also the translation procedures and the translation results upon which the final research findings are based. Some studies utilise complex translation processes and the involvement of numerous translators and translation reviewers, which are generally beyond the resources available for research students (Chen & Boore, 2009; Regmi, Naidoo, & Pilkington, 2010). It could be suggested that the reliance on such a complex and multi-partied translation process, as described in the literature, is necessary because many of these studies were written by mono-lingual researchers who depend on third-party translators to understand data gathered in a language and cultural context foreign to them (Squires, 2009; Croot, Lees, & Grant, 2011). In contrast, there is limited literature that delves into the issues faced by bilingual qualitative researchers. In light of the complex issues mentioned above, this paper attempts to compare specific translation procedures employed in two case studies and how the resource limitations in each study have been addressed from the perspective of bilingual researchers. Lessons learned from these case studies may be valuable for other bilingual researchers facing similar circumstances in clarifying their translation procedures and demonstrating trustworthiness in cross-language research. The two case studies described in this paper involve the translation from: 1) Indonesian to English, and 2) Vietnamese to English and the focus is on written translation, rather than oral interpretation. Translation equivalence Appreciating how linguists have understood the different conceptualisations of equivalence is informative for the two case studies in determining which equivalence conceptualisation to be pursued in the translation process. Equivalence has been supported and rejected by different factions in linguistics and translation studies (Kenny, 2009). Those who reject equivalence view that it is irrelevant and blocks the progress and creativity in translation as it is difficult to determine what constitutes equivalence between languages. Others view that without having some set criteria regarding equivalence, it is impossible to decide which text is a translation and which one is not (Brislin, 1970; Kenny, 2009). Baker (2011) contends that the concept of equivalence can be accepted for the sake of convenience in discussing translation. While some sort of equivalence can be obtained, there are so many language and culture-specific factors that obtaining absolute equivalence is unattainable (Baker, 2011; Kenny, 2009). The difficulties in achieving absolute equivalence can be seen upon examining the building blocks of a language (Kirkpatrick & van Teijlingen, 2009; Larkin et al., 2007). Often, the most basic way of determining equivalence is by examining the correspondent words in the source language and the target language—lexical equivalence (Baker, 2011). For example, the word rice in English is equivalent to the word padi in Indonesian or cơm in Vietnamese. However, rice can also be translated as gabah, beras, and nasi or lúa, thóc, and gạo in Indonesian and Vietnamese respectively, depending on the stage of its development as a plant and the degree of its preparation as a dish. A word in the source language may have more than one equivalent in the target language and vice versa. There are also cases of no equivalence (Larkin et al., 2007; Squires, 2008). Following the previous example of nouns related to food, the Australian cake lamington does not have any proper equivalence in Indonesian and Vietnamese. In addition, words do not make sense without the grammar that binds them together into sentences. In this sense grammar is a ‘straitjacket’ that locks a language into a particular way of thinking and of expressing ideas that in many cases do not translate into another language (Baker, 2011). For instance, with tense-free languages such as Indonesian or Vietnamese, translating accurately into English is a challenge. Unless there are explicit temporal adverbs, it is impossible to tell whether an Indonesian or Vietnamese sentence is in the present, past or future tense. As such, aspiring to develop some set criteria to evaluate equivalence and establish trustworthiness of translation results based on the equivalence of words or sentences is a simplistic idea that does not correspond to the complexity of language systems as observed by linguists (Liamputtong, 2010; Temple & Young, 2004). For these and many other reasons, lexical equivalence has been abandoned and conceptual equivalence has acquired more support in cross-language research (Larkin et al., 2007; Squires, 2008). Conceptual equivalence can be seen as the comparability of concepts or ideas between two languages, rather than the exact similarity of lexical meanings across languages (Birbilli, 2000; Neuman, 2011). For example, some nuances of meaning in the source language may be altered when conveyed in the target language (Baker, 2011). Although conceptual equivalence is striven for, it is still necessary to consider how information is structured in one particular language, how speakers of the language maintain coherence of ideas and cohesion of statements, and how the language users manipulate expressions and utterances to achieve humour, conceal feelings and assert opinions. Indeed, it is impossible to list all the variables involved in the process of translating a text (Baker, 2011). Through the notion of conceptual equivalence translators may subjectively determine the best translation result they want as there is no absolute equivalence to pursue. However, this approach may yield translation results that are unchecked and purely subjective, jeopardising the trustworthiness of the entire research (Liamputtong, 2010). Rather than pursuing lexical and conceptual equivalences, some linguists propose dynamic equivalence as a more acceptable goal in translating a text (Constantinescu, 2010; Nida, 1969). The emphasis on reproducing the message from the source language to the target language in the most natural manner is called dynamic equivalence (Constantinescu, 2010; Nida, 1969). Arguably it has been the most prominent way of understanding equivalence among translation theorists (Munday, 2008). Accuracy of the translation is then evaluated by virtue of examining the target language users’ ease of understanding and acceptance of the translation text (Constantinescu, 2010; Nida, 1969). Dynamic equivalence seemingly puts many translation theorists in general agreement that the trustworthiness of translation is not seen as universal and totally neutral. According to Baker (2011), “It is in fact virtually impossible, except in extreme cases, to draw a line between what counts as a good translation and what counts as a bad one. Every translation has points of strengths and points of weakness, and every translation is open to improvement” (p. 6). Translation can be seen as a dialogue between the original texts in the source language and the translated texts in the target language, mediated by the translator, which results in a co-dependence between the two texts (Baker, 2011). However, adherence to dynamic equivalence may shift the focus from the particular nuances contained in the source language to what is deemed understandable in the target language (Croot, Lees, & Grant, 2011). Hence this approach may not be preferred by researchers who want to emphasise the perspective of the source language users. From the above discussion, conceptual and dynamic equivalence have relevance for the two case studies. For example, conceptual equivalence was deemed more acceptable for the first case study. Provided it is combined with appropriate translation procedures, the subjectivity issue can be reduced. Dynamic equivalence, used in the second case study can be useful when the research agenda is to produce translation results that can be fully grasped by the target language users. For example, as research students who need guidance for the data analysis process, there may be a need to provide the English mono-lingual supervisory team translated data that can be fully grasped by English speakers. Implementation of these two concepts in the case studies are explored further later in this paper. As the more theoretical issues in translation have been discussed, the focus now turns to the practical translation procedures. Common translation procedures in qualitative studies There are three common procedures of translation that can be employed in qualitative studies: single translation, back translation and parallel translation (Liamputtong, 2010; Neuman, 2011). These procedures are examined in light of the previous discussion on equivalence, to identify a procedure suitable for the two studies and the translation limitations faced by the authors of this paper. Single translation is perhaps the most straightforward procedure where the data is translated from the source to the target language (Neuman, 2011). It is often the least complicated and the quickest procedure in finalising the result. Due to its straightforward nature, the single translation procedure is also perhaps the weakest in ensuring transparency and trustworthiness since single translation only relies on the skills and interpretation of one translator, without any comparison process and input from others (McGorry, 2000). To improve the trustworthiness of the single translation result, the dynamic equivalence approach perhaps can be adopted by bilingual researchers undertaking single translation procedure. This requires the bilingual researcher to corroborate the translation results with one or more native speakers of the target language to produce results easily understood by the target language users, hence reducing personal bias and increasing transparency in the translation process. Back translation procedure is widely used in social science research because of its potential to minimise inaccuracies in the translation with a result that strives for equivalence across languages (Liamputtong, 2010; Lopez et al., 2008). In this procedure, two translators are employed. One translates from the source to the target language. The other translator translates back the data from the target to the source language without knowing the original source language version (the back translation) (Brislin, 1970). The back-translation version is then compared with the original version in the source language. The comparability between the back-translation version and the original version is considered to indicate translation accuracy (Douglas & Craig, 2007). Compared to the single translation procedure, back-translation provides more opportunities for filtering translation errors as there is more than one translator involved. Another advantage is the researcher does not have to be a bilingual to participate in examining the translation accuracy (Chen & Boore, 2009; Jones et al., 2011). Nevertheless, the use of back-translation for a whole data set tends to be avoided given its laborious and lengthy process (Chen & Boore, 2009; Guest, Namey, & Mitchell, 2013). In addition, as stated earlier, a word-to-word equivalence between two languages does not always exist and examining conceptual equivalence between the texts can be challenging. However, there are ways that back translation can be used by bilingual researchers and this is described below. First, the bilingual researchers can assign the translation to two third-party translators. The bilingual researcher can then take the role as the evaluator of the back-translation results (Guest, Namey, & Mitchell, 2013). This may give the researchers a sense of involvement in the translation process and allow them to understand the complexities of the translation process. Evaluating the back-translation results may also improve the accuracy, providing more pairs of eyes to re-check and triangulate the results. Alternatively, bilingual researchers can take part actively in the back-translation process as the first translator. The back-translation can then be undertaken by a third-party translator and the backtranslation results can subsequently be compared with the original texts in the source language. If there are inconsistencies, the bilingual researchers can revise the translation into the target language. This scenario can be more financially viable compared to engaging two third-party translators. More recently, researchers and theorists have proposed the use of parallel translation, also known as the team or committee approach (Douglas & Craig, 2007; Lopez et al., 2008). Parallel translation is done by involving two or more translators to translate from source to target language independently. The different translation transcripts are then compared to come up with the best translation version (McGorry, 2000; Neuman, 2011). Parallel translation is considered as one of the more effective translation procedures as it minimises translation errors through extensive checking and evaluation with a panel of translators and experts (Douglas & Craig, 2007). A comparison of several results in the target language may increase the possibility of identifying the most appropriate translation version (Liamputtong, 2010; Lopez et al., 2008). However, this procedure may be as costly and time consuming as back-translation due to the number of people involved and the consultation process (Guest, Namey, & Mitchell, 2013). In addition, the relatively similar cultural and educational background of translators and experts may influence how they translate the data and understand the social realities of the research participants, skewing the final translation result towards their own interpretation, rather than the research participants’ original voice and opinion (McGorry, 2000). Unlike the back-translation procedure which allows comparison between the original text in the source language and the back-translated text, the parallel translation procedure only produces texts in the target language so the results are mainly geared towards the comprehension of the target language users, not the source language users. Ideally, at least one of those parallel translators is also a native speaker of the target language so that dynamic equivalence can be attempted in an efficient manner. Bilingual researchers can play several different roles in parallel translation, as translators, evaluators, or even both, depending on their qualification and experience in translation. To improve the trustworthiness and transparency of cross-language research, Squires (2009) introduced evaluation criteria that incorporate aspects of the translation process and the qualitative research methodology. These evaluation criteria are examined in the next section, paying particular attention to how the criteria relate to the issue of equivalence and the roles of bilingual researchers. Translation evaluation criteria for qualitative data Having reviewed the existing literature of cross-language research methods, Squires (2009) proposed several criteria that can be used as a consensus to evaluate trustworthiness of cross-language qualitative studies. These criteria include conceptual equivalence and various aspects of the translator’s role and credentials, such as language proficiency in both languages used. As Squires’ (2009) criteria have been evaluated in great extent from the perspective of mono-lingual researchers (Croot, Lees, & Grant, 2011), the discussion in this section selectively address some criteria pertinent to bilingual researchers. There are several strengths of Squires’ criteria for bilingual researchers. For instance, Squires suggests a need for clarification of the language proficiency of the researcher and qualification of the translator. Being bilingual does not always correspond with having the required skills to undertake translation of rich qualitative data (Squires, 2009). Bilingual researchers need to evaluate their own qualifications and experience in translation before taking part in the translation process. Squires also emphasises employing a third-party to validate the translation. In the absence of reliable evaluation criteria and consensus on what constitutes trustworthy qualitative data translation, Squires’ criteria can be useful as a sensitising device to assist choosing the appropriate translation process and to improve its transparency (Croot, Lees, & Grant, 2011). However, these criteria cannot be taken as a universal consensus that applies to all qualitative studies given the multiple worldviews and diverse research aspirations that qualitative studies embody (Croot, Lees, & Grant, 2011). To be more practically informative, Squires’ criteria may need to be broadened to address specific concerns of novice bilingual research. For example, Squires does not specifically mention the role of researchers in the translation process. The criteria ask for clarification on the researchers’ language proficiency and role of the translator in the research, but they stop short of including the role that researchers may want to undertake during the translation process. This is particularly important for bilingual researchers who can play many roles during the translation process as outlined above. Second, the criteria do not explicitly acknowledge resource limitations that need to be taken into account in the translation process. For instance, emphasising on validating the translation results with qualified experts in translation may be difficult for languages that are less- or under-studied (Guest, Namey, & Mitchell, 2013). Moreover, services from these experts can be financially burdensome. Time limitation in the research project may also hamper a meaningful validation process. Mapping out the resource limitations, such as time, funding, and expertise in translation should be carefully observed. Finally, Squires’ focus on conceptual equivalence may not apply to researchers seeking dynamic equivalence. Some researchers may not want to emphasise the participants’ voices, but they want to improve the target language users’ comprehension of the translation. These issues along with Squires’ existing criteria are considered by the two case studies described in the following section. Two translation case studies Heeding the discussion outlined in the previous sections, the main concern in incorporating translation in qualitative research is to explicitly articulate the rationale behind the translation procedure employed, the roles played by the translator and bilingual researcher, and the mitigation of issues that may influence the trustworthiness of the research findings (Croot, Lees, & Grant, 2011; Squires, 2009). Therefore, the reasons for selecting a particular translation procedure and the overall stages undertaken for the two case studies are elucidated in this section with the express aim of improving transparency and trustworthiness in both studies. In the first case study, a back-translation procedure was used with an emphasis on conceptual equivalence, whereas in the second case study, a combination of single translation and partial parallel translation was used with the emphasis on dynamic equivalence. Case study 1: Indonesian – English The first case study concerns knowledge transfer between Indonesian and Australian universities through joint transnational higher education programs and was conducted in English and Indonesian for the first author’s dissertation submitted to an Australian university. This case study involves collecting data in two Indonesian universities and one Australian university, with an emphasis on the perspectives of managers and lecturers from the Indonesian universities. As these programs were delivered in English, it was initially envisaged that all the interviews would be conducted in English, to align with the interviews in the Australian university that would be done in English. However, during the validation of the interview questions with some Indonesian lecturers, it was suggested that the interview questions be made available in Indonesian as a precaution that not all the intended participants would be willing to be interviewed in English. Consequently, the first author, who is an Indonesian and English bilingual and was a professional translator in his earlier career, translated the questions into Indonesian. This would prove to be valuable as not all the Indonesian participants were willing to speak in English during the data collection in Indonesia. In total, there were thirteen out of twenty participants from the Indonesian universities, who were interviewed in Indonesian. After the interviews were completed, they were transcribed by an independent transcriber with the researcher re-checking the transcripts to rectify errors and ensure compliance with transcription convention. Once completed, the transcripts were sent to the interviewees to ask for their input and to ascertain that the transcripts represented what they actually talked about in the interviews. There were nine participants whose input and feedback to the transcripts were incorporated into the final transcripts, and subsequently the transcripts were sent to a translator. As recommended by Squires (2009), it is necessary to explain the credentials of the translator and clarify the translation process. The translator chosen for the project was a certified translator who was also a lecturer in translation studies at a leading Indonesian university. Given her credentials and her knowledge about the operation of an Indonesian university, it was expected that she would provide an accurate translation. Although the researcher could have undertaken the translation himself, engaging a third-party translator was done to minimise any subjectivity. After the translator finished the translation, the researcher re-examined the translated transcripts. There were two purposes for reexamining the transcripts at this stage. First, the researcher sought for errors in translation. This might have arisen due to unclear punctuation in the original Indonesian transcripts that could blur the meaning of the utterance. To screen for errors, the researcher re-listened to some of the recording to clarify what was uttered by the interviewee and how it was transcribed and translated. This process also sought to eliminate possible sentences that were mistranslated because the translator did not fully understand the context of the utterances. Second, the researcher identified sentences and words which he did not fully agree with in the translator’s interpretation and made these corrections. To corroborate the translated transcripts, a back-translation procedure was utilised. Back-translation was preferred over parallel translation in this study as the study’s focus was exploring the Indonesian participants’ perspectives and experience. By undertaking back-translation, it was possible to assess whether or not the Indonesian to English translation was well understood by another Indonesian speaker, who in this case was the back-translator. The back-translated transcripts were also compared with the original Indonesian transcripts to examine whether or not the conveyed perspectives were comparable to what the interviewers articulated initially. In adopting this approach it was possible to consider the back-translator as a qualified third party in validating the Indonesian to English translation results (Squires, 2009). If the back-translator can understand and re-articulate the information back into Indonesian, the translation can be viewed as trustworthy. Once the researcher finished re-checking the translation from Indonesian into English, the translated transcripts were sent to another translator who was asked to translate the English version into Indonesian. This back-translator was also an Indonesian certified translator, fluent in both English and Indonesian. After the back-translation transcripts were returned to the researcher, they were examined and compared simultaneously with the original Indonesian transcripts and the English transcripts. Sections that differed markedly were highlighted and the researcher suggested changes to the English version. Following the back-translation procedure, the researcher compared the back-translated transcripts with the original Indonesian transcripts. In line with the notion of conceptual equivalence, a comparison was done at the sentence level with the results yielding a 94.69% correspondence. Given the high level of similarity and the added timing constraint for the research, it was decided that the translation procedure would not incorporate convening a panel of translation experts. As Indonesian is not widely studied compared to some of the major world languages, experts in Indonesian-English translation were rather limited and were not located in a geographical area that would allow the first author and the translators to come together to have a meaningful discussion. Once the back-translation process was completed, the translation of the data into English was finalised. This final translation result was used for analysis, along with the data gathered in English from the Australian university. Overall the process took six months to complete, starting from the transcription process until the finalisation of translation. Figure 1 illustrates the translation procedure in this study. Figure 1: Translating Indonesian to English Role of Translator Transcriber and Procedures Role of Researcher Formulate and Validate the Questions Interview English Questions in Interview Indonesian Questions in Translate into Indonesian Conduct the Interview Interviews in Indonesian Transcriber A: Transcribe in Indonesian Check the Transcription Transcription in Indonesian Translator A: Translate into English Check the Translation Result Translation in English Translator B: Back-translate into Indonesian Check the Back-translation Result Back-translation in Indonesian Compare the Original Indonesian and Backtranslation Versions Final Version in English Analyse the Data in English Findings in English Write the Report in English Report in English Conceptual equivalence and back-translation were combined effectively in this first case study. Backtranslation for the entire data set ensured that the data were treated with equal level of scrutiny and the errors were minimised. The researcher firstly examined the similarity between the original (Indonesian) transcripts and the translated (English) transcripts by paying more attention to the similarity of ideas rather than linguistic units at word and phrase levels. The final comparison of the original transcripts and the back-translated transcripts was also done in accordance with the conceptual equivalence principles, as it was at a sentence level, rather than word-by-word correspondence. Hence, the final translated transcripts were minimal in errors, yet still retained the Indonesian speakers’ perspectives. Case study 2: Vietnamese – English The second case study was the second author’s dissertation for her doctor of philosophy of education at an Australian university. The study explored learner autonomy in Vietnamese higher education, a relatively new concept, particularly for English as a foreign language (EFL) teaching and learning. Grounded in the social cognitive theory, this exploratory study investigated the extent to which Vietnamese lecturers understood the concept and how their beliefs about learner autonomy were applied in teaching EFL. The stimulated-recall interview (SRI) technique was employed in this study to explore the association between teachers’ beliefs and their behaviour to gain unique insights into why teachers choose to act in certain ways from various options (Dempsey, 2010). Four Vietnamese lecturers were interviewed using the SRI technique. There were a total of twenty interviews from four cases, which included four initial interviews, twelve stimulated recall interviews, and four follow-up in-depth interviews. In the following paragraphs, the constraints that the researcher encountered in translating data from Vietnamese to English and the justifications in including both a single and partial parallel translation procedures are presented. As in the first case study, prior to the data collection, validation of the interview questions was conducted. The second author asked the four participants if they wished to be interviewed in English or Vietnamese and all of them preferred to be interviewed in Vietnamese. Subsequently, the interview questions, originally in English, were translated into Vietnamese by the researcher who has both linguistic and cultural mastery in Vietnamese and English contexts. Given the researcher’s background as a former English lecturer at a Vietnamese university and her prolonged stay in Australia as a research student, she understood the participants’ cultural and social backgrounds and fully comprehended both English and Vietnamese. Hence, the researcher was deemed the best person to translate the interview questions (Liamputtong, 2010), thus, meeting the first criterion proposed by Squires (2009) in relation to establishing the translator’s credentials. The researcher then undertook transcription of all the interviews in Vietnamese. The transcription process involved listening to the interview tapes several times during which notes were taken about the tones of voice used by participants when describing their experiences, pauses in conversation, and emphases on certain points which were important to the participants. These notes were taken as future reference points during the analysis process. On completion of the transcription, the main issue was deciding the subsequent process: translating the transcription into English or analysing the data in Vietnamese? While Squires (2009) recommended that the analysis should begin in the source language, the researcher decided to translate the transcripts into English. Conducting the analysis in the source language then applying back translation to translate the study’s findings may alleviate the time and financial constraints and maintain the trustworthiness of the qualitative study (Chen, & Boore, 2009). However, the researcher decided not to use this procedure for three main reasons. First, the researcher in this study was a PhD student who needed guidance from her supervising team who were monolingual English speakers. They would not have been able to provide guidance for the data analysis if the data had been in Vietnamese. Second, it was complicated to obtain the equivalence for the term learner autonomy in Vietnamese. The term can be translated differently into Vietnamese and each version reveals the translator’s connotation and perspective, which would have had influence on the interviewees’ perspectives and understanding. For example, learner autonomy is equivalent to tính chủ động của người học which takes learners’ ability or capacity into account, based on the psychological perspective (Benson, 1997). Learner autonomy can also be translated as sự chủ động của người học – the technical perspective (Benson, 1997). This perspective views learner autonomy as a “situational” where learners are completely responsible for the performance of their learning activities (Chang, 2007; Smith, 2008). Therefore, in order to avoid such complication, the researcher decided to keep this key term in the target language during her interviews. Moreover, during the interviews, the participants sometimes used English to express some phrases or terms. Consequently, the transcripts contained a mixture of English and Vietnamese phrases. This was another factor that led to the decision of translating all interviews into the target language before analysing the data using NVivo—a qualitative data analysis software, because NVivo cannot effectively run in two different languages simultaneously. Therefore, the researcher decided to first translate the interviews from Vietnamese into English using the single translation procedure, include some parallel translation after the initial single translation, and then analyse the data. However, mindful of trustworthiness and equivalence issues, a third-party translator and a native English proof-reader were involved in this study, thus, introducing a parallel translation procedure. After the researcher translated all interview transcripts from Vietnamese into English, a certified Vietnamese-English professional translator (Vietnamese) was employed to translate three pieces of the interviews into English (i.e. one initial interview, one stimulated recall interview, and one followup in-depth interview). The next step was comparing these two versions of translated transcripts in order to minimise errors in the translation completed by the researcher. The comparison was also done at the sentence level with the results yielding a 93.01% correspondence. Subsequently, lessons drawn from the initial comparisons were expanded to review the other transcripts. Finally, in line with the idea of dynamic equivalence, to gain the final version which most native speakers would understand, an English-speaking proof-reader was employed to examine all the translated transcripts and provide input and corrections. Thus, with the translation procedures used in the second case study, the bias in the research was minimised and its trustworthiness was sustained. The entire data transcription and translation process took two months. Figure 2 below is an illustration of the translation method used for this study. Figure 2: Translating Vietnamese to English Role of Translator and Proofreader Procedures Role of Researcher Formulate and Validate the Questions Interview English Questions in Translate into Vietnamese Interview Vietnamese Questions in Conduct the Interviews Interviews in Vietnamese Transcribe the Interviews Transcription in Vietnamese Transcribe and Check Translation in English Translator A: Translate Three Interviews into English Parallel Translation in English Consult the Translator and Consolidate Inputs English Version to be proof- read Proof-reader A: Provide Corrections and Inputs Consult the Proof-reader and Finalise Final Version in English Analyse the data in English Findings in English Write the Report in English Report in English This second study adhered to the notion of dynamic equivalence and incorporated single and partial parallel translation procedures in an efficient manner. The bilingual researcher single-handedly translated the entire data set and assigned a third-party translator to undertake translation of a smaller data set. A smaller scale comparison was done between the transcripts translated by the researcher and the other translator with the intention to determine the accuracy of the researcher’s translation and extend lessons learned from the comparison to the remaining data set. This was done to overcome resource limitations without sacrificing the pursuit of high-quality translation results. The dynamic equivalence was achieved by consulting a native English proof reader who ensured that the linguistic expressions were easily comprehended by the target language users (i.e. English). Consequently, the researcher produced translation results easily accessible for her research supervision team and other English readers. Hence the overall study was more transparent and open for guidance and improvement from more experienced researchers. While the two case studies differed in many ways, the underlying principles that the researchers used have some similarities. In both case studies, the planning, decisions, and final reporting were conducted, and monitored by the bilingual researchers to ensure that the translation procedures had been conducted in the most rigorous manner (Kirkpatrick & van Teijlingen, 2008; Squires, 2008). As a bilingual, the researcher is the one that has the greatest potential to understand the research intentions and the linguistic complexity and, therefore, responsibility of rigor rests with the researcher (Liamputtong, 2010). Nevertheless, the inclusion of the third parties lent more pairs of eyes to increase the accuracy of the translation and reduce personal bias in the single translation procedure. Discussion The two case studies described above were checked against Squires’ (2009) key recommendations. Regarding the conceptual equivalence criteria, both studies have provided rationales for utilising English as the language for data analysis and to ensure trustworthiness and equivalence in the translation. For example, it has been argued that because of the authors’ dissertations were written in English, it was necessary to use English as the language for data analysis and reporting. The translation results in the first case study were scrutinised mainly by means of back-translation by third-party translators. The researcher as a bilingual and former professional translator evaluated the translation results using the conceptual equivalence notion to determine the level of similarity between the original and the back-translated transcripts. In the second case study, the notion of dynamic equivalence was more prioritised than conceptual equivalence as the study sought to ensure that the mono-lingual supervision team could fully understand the content of the data. While the researcher acted as the main translator, a third party translator and English native speaker proof-reader were employed, hence complying the translation results with the notion of dynamic equivalence, reducing personal bias, and minimising translation errors. Concerning the credentials of the translators, their qualifications, suitability and capacity to undertake the translation have been argued for. In addition, both bilingual researchers have had experience in translation procedures in the earlier parts of their career. Hence, the language competence of the people involved in the two translation procedures bears up to scrutiny. In relation to the translator role criteria, the two studies have attempted to follow Squires’ (2009) recommendations to clarify the research stages when translators are involved and the number of participating translators. In case study one, the researcher mainly considered the role of translators as his aides in ensuring that a high quality of translation had been achieved. At the request and supervision of the researcher, the translators were tasked with translating and back-translating the data. The use of back-translation in the first study was seen as a way to ensure that the translation did not stray from the participants’ perspectives. In the translation process, the translators were not involved in a discussion with the researcher as this is not normally required in the back-translation procedure (Guest, Namey, & Mitchell, 2013). Following Squires’ recommendation, only one translator was involved in translating the data from Indonesian into English, and only one translator was involved in the back-translation. This could be more time consuming compared to employing several translators simultaneously, but it was valuable as the two translators involved became highly familiar with the entire data set and provided consistent terminology and linguistic expressions in all the translated transcripts, hence increasing the trustworthiness of the translation results. In the second study the researcher was the main translator for translating the whole data set from Vietnamese into English. A certified translator was used for translating three out of twenty interviews, and a native English proof reader was used in reading the translated transcripts of the three interviews. This translation procedure was considered efficient as less time-consuming and costly to the researcher. Rather than adding complications, as postulated by Squires, the involvement of two translators for the Vietnamese-English translation was deemed necessary to minimise personal bias in the second study’s translation procedure. Unlike the first study, there was also more discussion between the researcher, the independent translator and the proof reader. These third parties were seen as collaborators by the researcher (Berman & Tyyskä, 2011). In agreement with Croot, Lees, & Grant’s (2011) assessment, Squire’s (2009) criteria’s main value for bilingual qualitative research is to increase the researchers’ awareness of complexities in translation. Further reflection on the criteria in these two case studies has lead the authors to consider their appropriate roles as bilinguals in the translation process, factor in potential resource limitations, plan alternative actions when Squires’ recommendations could not be implemented, and incorporate the notions of both conceptual and dynamic equivalence. In comparing the translation procedures in the two case studies, there are some potentially informative lessons for other bilingual researchers. First, researchers should be aware of the time, the financial, and the translation expertise limitations involved with translation procedures. In the first study, employing back-translation was time consuming and financially demanding. As a result, there was no adequate opportunity for the researcher to engage in meaningful discussion with the translator and back-translator to improve the translation quality. The study also could not employ a panel of experts to evaluate the translation given the limited nature of expertise in Indonesian-English translation. The first author, nevertheless, believes that conducting back-translation for all transcripts and personally double-checking the translation results increased the trustworthiness of the translation. There were extensive checks done by the translators and the researcher himself as a bilingual. This process was aimed at improving the accuracy of translation but was also used to give the researcher a sense of ownership of the entire research endeavour (Temple & Young, 2004). As noted above, the researcher found errors in the translated and back-translated transcripts. Hence, although the translators were qualified as Squires (2009) recommends, bilingual researchers are still responsible for re-checking the transcripts. In reference to the second study, the second author undertook the single translation procedure singlehandedly (Liamputtong, 2010). Given time and financial limitations, the second author used a partial parallel translation procedure. The comparison between her translation version and the independent translator’s translation version helped to improve the quality of the translation as lessons obtained from comparing the two translation versions from the smaller data set was extended to the other data. In this way, time and financial constraints were minimised. Finally, the selection between conceptual or dynamic equivalence needs to consider the research agenda and complements the selected translation procedure. The first author used conceptual equivalence in combination with back-translation procedure to produce translation results that adhere to the perspectives of source language users. The second author used dynamic equivalence in conjunction with single and partial parallel translation procedures to allow her research supervisory team greater access and comprehension of her data. As such, there was clear justification for opting one equivalence notion over the other. Conclusion This paper has described two different translation procedures for cross-language research. In particular, it has looked at the concept of equivalence in relation to a chosen translation procedure. It is clear that for novice researchers with resource limitations, their roles in the translation process needs to be carefully considered to maintain the trustworthiness of the data translation. By ensuring that the procedure aligns with up-to-date quality standards of cross-language qualitative studies, the two case studies outlined in this paper have demonstrated the need for transparency to improve trustworthiness in cross-language qualitative research. Whilst striving for trustworthy research, there are limitations that cannot be avoided in the two case studies. For example, the final result of the translation to a certain extent depends on the judgment made by the researchers. Those interested in emulating the translation procedures outlined here need to consider how these procedures fit with their own research goals. In other words, there is not a onesize-fits-all procedure of translating qualitative data. Nevertheless, following some of the recommendations promulgated in this paper and paying attention to the recent positions of translation experts and qualitative methodology theorists, the procedures for translation of data described for the two case studies may be useful for bilingual researchers who are engaged in qualitative crosslanguage research and who may face similar limitations acknowledged here. References Baker, M. (2011). In other words: A coursebook on translation (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. Benson, P. (1997). The philosophy and politics of learner autonomy. In P. Benson & P. Voller (Eds.), Autonomy and independence in language learning (pp. 18-34). New York: Longman. Berman, R. C., & Tyyskä, V. (2011). A critical reflection on the use of translators/interpreters in a qualitative cross-language research project. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 10(1), 178-190. Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185-216. doi: 10.1177/135910457000100301 Chang, L.Y. (2007). The influences of group processes on learners’ autonomous beliefs and behaviors. System, 35, 322-337. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2007.03.001. Chen, H. Y., & Boore, J. R. (2009). Translation and back-translation in qualitative nursing reseach: Methodological review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 19(1-2), 234-239. doi: 10.1111/j.13652702.2009.02896.x Croot, E.J., Lees, J., & Grant, G. (2011). Evaluating standards in cross-language research: A critique of Squires’ criteria. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 48 (8), 1002-1011. Constantinescu, A. (2010). Nida's theory of dynamic equivalence. Linguistic and Philosophical Investigations, 9, 284-289. Dempsey, N. P. (2010). Stimulated recall interviews in Ethnography. Qualitative Sociology, 33, 349367. doi: 10.1007/s11133-010-9157-x. Douglas, S. P., & Craig, C. S. (2007). Collaborative and iterative translation: An alternative approach to back translation. Journal of International Marketing, 15(1), 30-43. Fryer, C., Mackintosh, S., Stanley, M., & Crichton, J. (2012). Qualitative studies using in-depth interviews with older people from multiple language groups: Methodological systematic review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68(1), 22-35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05719.x Guest, G., Namey, E. E., & Mitchell, M. L. (2013). Collecting qualitative data: A field manual for applied research. Los Angeles: Sage. Jones, P. S., Lee, J. W., Philips, L. R., Zhang, X. E., & Jaceldo, K. B. (2011). An adaptation of Brislin's translation model for cross-cultural research. Nursing Research, 50(5), 300-304. Kenny, D. (2009). Equivalence. In M. Baker & G. Saldanha (Eds.), Routledge encyclopedia of translation studies (pp. 96-99). London: Routledge. Kirkpatrick, P., & van Teijlingen, E. (2009). Lost in translation: Reflecting on a model to reduce translation and interpretation bias. The Open Nursing Journal, 3(1), 25-32. doi: 10.2174/1874434600903010025 Larkin, P. J., de Casterlé, B. D., & Schotsmans, P. (2007). Multilingual translation issues in qualitative research: Reflections on a metaphorical process. Qualitative Health Research, 17(4), 468-476. doi: 10.1177/1049732307299258 Liamputtong, P. (2010). Performing qualitative cross-cultural research. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park: Sage. Loos, E. E., Anderson, S., Day, D., Jordan, P., & Wingate, J. (2004). Glossary of linguistic terms Vol. 29. Retrieved from http://www.sil.org/linguistics/GlossaryOfLinguisticTerms/Index.htm Lopez, G. I., Figueroa, M., Connor, S. E., & Maliski, S. L. (2008). Translation barriers in conducting qualitative research with Spanish speakers. Qualitative Health Research, 18(12), 1729-1737. doi: 10.1177/1049732308325857 McGorry, S. Y. (2000). Measurement in a cross-cultural environment: Survey translation issues. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 3(2), 74-81. doi: 10.1108/13522750010322070 Munday, J. (2008). Introducing translation studies: Theories and applications (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. Neuman, W.L. (2011). Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches (7th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. Nida, E. A. (1969). Science of translation. Language, 45(3), 483-498. Regmi, K., Naidoo, J., & Pilkington, P. (2010). Understanding the processes of translation and transliteration in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 9(1), 1626. Smith, R. (2008). Learner autonomy. Key concepts in ELT, 62(4), 395-397. doi: 10.1093/elt/ccno38. Squires, A. (2008). Language barriers and qualitative nursing research: Methodological considerations. International Nursing Review, 55(3), 265-273. doi: 10.1111/j.14667657.2008.00652.x Squires, A. (2009). Methodological challenges in cross-language qualitative research: A research review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46(2), 277-287. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.08.006 Temple, B. (2002). Crossed wires: Interpreters, translators, and bilingual workers in cross-language research. Qualitative Health Research, 12(6), 844–854. doi: 10.1177/104973230201200610 Temple, B., & Young, A. (2004). Qualitative research and translation dilemmas. Qualitative Research, 4(2), 161-178. doi: 10.1177/1468794104044430 UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2011). Global education digest 2011: Comparing education statistics across the world. Montreal: UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Wong, J. P.-H., & Poon, M. K.-L. (2010). Bringing translation out of the shadows: Translation as an issue of methodological significance in cross-cultural qualitative research. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 21(2), 151-158. doi: 10.1177/1043659609357637